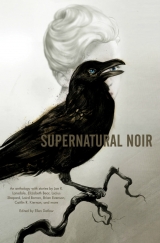

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The poles impaling the standing animals are the ones that support the platform. She can almost feel the weight of it, the tension, prickling her palm. If she’d thought about how the carousel was constructed, she realizes now, she must have thought the turntable rested on bearings, but really it’s cantilevered out on sweep arms, and those arms are supported by the poles that hang from above. The whole things turns around one central pillar.

She discards two dustpans’ worth of debris, starts on the third. Now she’s working around the lion and the tiger and the out-of-scale elephant, and in a moment she’ll be back to the gray ponies. That’s probably where she should dump; there will be another dustpanful at least in the rest of the carousel. As she passes, she can’t resist the urge to pet the ugly filly on the nose.

Velvet skin and hot breath tickle her fingers.

With a wheeze, the Wurlitzer shudders to life. The carousel begins to turn with a savage jolt that sets January teetering. Pain stabs her ankle. It stretches as her Mary Jane rolls sideways and the tendons give. The broom skitters from her hand as she windmills like Wile E. Coyote on the edge of a cliff. If she falls backward into the center of the carousel, the sweep arms will catch her and drag her over the concrete floor.

She flails, diaphragm tightening, fingertips splayed. Gravity pulls her down. But as the fall becomes inevitable her right hand slaps something rigid, closes on it, pulls hard. She remembers reading about panic strength, how in extreme peril your body discards the safety margins and does whatever it has to do, whatever it can, to get you out of harm’s way.

She’s never experienced it before.

When she comes back to herself, she’s breathing raggedly, in deep concentrated gasps that hurt her trachea and lungs. For a moment, those breaths are all she can think about, until a moment later the burn in her bicep and forearm makes its presence known.

The foreleg of the gray filly is clutched in her hand. It is no longer attached to the filly.

The thing protruding from the broken end is not a metal bar, but a snapped-off length of bone.

January knows she should scream, but apparently she’s not the screaming type. She stands there looking at the horse’s leg, at the place where the horse’s leg used to attach, at the two cleanly broken ends of bone. Human bone, she can’t help but think, but how would you know for sure? She’s read that even homicide cops have to send skeletal remains out for testing sometimes to be sure if they have uncovered the remains of a person or of an animal.

Like a child with a broken toy, she tries to slot the stiff wooden leg back onto the body of the filly. It fits, but of course it won’t stay. So January stands holding it, feeling foolish and terrified, her heart still churning residual adrenaline through her veins. In a minute, she will start to shake. She’d rather not do that while she’s still stuck on a malfunctioning carousel.

With a corpse, the helpful part of her brain volunteers.

They probably used horse skeletons as the form for the ponies. The ponies she’d been riding on. Like the real manes and tails, and she’d thought that was macabre.

Real horses aren’t this small. Real people are.

“Shut up,” she says. “We have to get off this thing.”

She can’t figure out what else to do with the filly’s leg, so she holds it in her hand as she moves to the center of the deck. The carousel is going faster than before. Inexorably, it’s accelerating. It seems as if the Wurlitzer is accelerating with it, though she can’t think of any reason why they would be geared together. The music has a hysterical edge.

Which, in fairness, January could be imagining.

Threading between horses, holding onto the brass sleeves surrounding the steel poles, January tries not to touch the glossy, brilliant paint where a few moments ago she lingered to stroke it. Is there something dead inside every one of them? Is it possible she’s tripping and none of this is real?

Holding onto the lion’s pole—easier than the gray stallion’s, because the lion does not go up and down—January leans as far out as feels safe. The carousel is whipping fast now, the wind slapping her hair to sting her cheeks and the corners of her eyes. Jeff, Martin, and the carousel operator stand in a tight huddle. Jeff gesticulates; the carousel operator shakes her head. January can’t hear a word over the Wurlitzer.

She draws a breath and shouts as she comes around. “Hey!”

Martin’s head jerks up and he’s about to shout something when she’s carried around the curve. When she comes back, he’s ready. “Sit tight! We have a plan!”

A good plan, she hopes. One that doesn’t involve damaging her or the carousel. Any more than she’s already damaged it, that is.

When she comes around again, Jeff is sprinting beside the rotating platform. Running hard, too, which gives her an idea of how fast she must be moving, because he’s losing ground. He reaches out as the lion gains on him and she steps back to make a landing zone. He jumps, arms swinging, and lands lightly beside her, one hand making contact with the lion’s support pole where hers had rested a moment before.

“Great,” January says. “Now you’re stranded too.”

He grins, flush with success. “The motor’s in the middle,” he says. “If I can reach—”

A thump cuts him off, a sharp wooden thud as the lion statue twists and lashes out with one gilt-clawed forepaw. January has a thousand years to watch Jeff’s expression of pained surprise as he topples backward off the carousel, a spray of blood scattering from his slashed thigh. January reaches for him instinctively, the broken leg of the gray filly falling to the deck, but all she feels is the brush of his warm, clutching fingertips against hers and then he’s gone. She almost throws herself after but something unyielding blocks her: the lion’s leg, extended like a crash barrier.

She withdraws, shuddering, into the second file. The tiger’s no better, objectively, but at least she has yet to see it move.

The next time the carousel brings her around she sees Martin hurtling the barrier, crouching beside Jeff. The time after that Jeff is up and hobbling, Martin supporting him, both of them holding a bandage made of Martin’s shirt over the gash on Jeff’s thigh.

“We’ll try something else!” Jeff shouts, but it sounds far away. Misty, if things can sound misty, exactly.

“Don’t!” January yells back, after one more revolution. “Call an ambulance.”

The carousel operator has her cell phone in her hand; it doesn’t look like she was waiting for instructions on that front. January blesses sensible women and looks left and right for the gray filly’s leg, but it’s not in sight anywhere. Maybe the same centrifugal force that wants to hurl her off the carousel when she leans too far out has sent it spinning over the side.

Because she doesn’t have any idea what else to do, she goes back to the gray filly. It feels like home base, and it’s farther from the lion. She has a hard time making herself touch it at first, but eventually stops snatching her fingers back as if she expected the lacquered wood to be hot and leans on the filly as she bobs up and down, trying to feel warm flesh and living bone under satin hide once more.

She didn’t imagine it. She didn’t imagine what the lion did to Jeff, the momentary glint of intelligence in its glass eye. She didn’t imagine the way the filly stretched under her petting.

The boom of the Wurlitzer hurts, now, so loud and so close. It’s almost impossible to think for the pounding of the base drum in her chest cavity. January imagines she can hear her brain ringing as it rattles from side to side against bone. She can’t think; she can’t jump; she can’t wait for rescue.

She has to do something.

Gingerly, teeth clenched, January leans on the sleeve and starts trying to fit her left foot into the iron of the undulating pony’s stirrup. She jams her clog in, her twisted ankle complaining, and takes a deep breath as the maimed filly’s ascent jerks her hip joint uncomfortably wide. As the pony comes down again, January jumps at the saddle, her skirt furling unevenly about her thighs. She’s grateful for the real horsehair tail now, because an arched carven one would have caught her hem and she would have fallen stupidly back to the deck and probably broken her leg. As it is, the skirt snags but tugs free, and she lands in the saddle only bruised on her inner thighs, clutching the pole and breathing hard through her nose.

You wouldn’t think something so simple could be so scary.

She passes beside the dispenser for the rings. A dull one sits in the socket at the end of the arm, though no one has filled the hopper. In the moment it takes for January to reclaim her composure, she cranes her head to see around the bigger horses rising and falling between her and the outside. She hopes for a glimpse of Martin or Jeff, but what she sees confounds her.

The carousel shelter is full of people once again. And not EMTs. These are people dressed as if they stepped out of the illustrations in a book on the sinking of the Titanic. The women wear tunics over long skirts, or shirtwaist blouses that give them a pigeon-breasted look. The men wear suits of gray and black woolen, cut curiously large. The children run in pinafores or short pants, the girls’ hair in ringlets and the boys’ parted razor straight and slicked. It looks like something out of a sepia-toned print.

The gray filly tosses her wire-slick mane and whinnies, harsh and loud as the scrape of the band organ. Her ears prick sharp as a carved horse’s, and January feels the crooked, staggering thud of hooves on the deck as her three-legged run struggles to keep up with the rise and fall of the pole. Her warm sides steam in the cold, muscles in her shoulder bunching and extending with each stride.

She tosses her head, fighting the bit. January finds herself rocking in time to the ragged gait, the muscle memory from long-ago riding lessons finding her balance and telling her to relax her arms and unclench her hands.

The filly calms, her ears flicked back as if listening. Alongside the carousel, a tall, rangy teenaged girl in a gray dress and high-heeled ankle boots runs skipping until January hears somebody call after her, chastising her as a hoyden and naming her—January.

“January?” January says, thinking suddenly, this is all a dream, I don’t care how detailed. But the filly’s ears flick, and the warm, grassy scent of her hide floats up as she shakes out her streaked silver mane. The filly bends her neck into an arc tight as a bow, lipping January’s knee, and January says the name again.

This time, the filly tosses her head yes.

“We’re namesakes.”

Another yes.

The animals all seem alive now. She can hear their noises, the trumpet of the elephant, the whinny of stallions, the lion’s deep cough—nothing like the sound children make to indicate lion. They seem to eye her balefully, so that she feels herself tucking her knees in tight and keeping her elbows close, as if by staying inside the footprint of the filly’s body she can protect herself from the malevolence of carved things.

The filly’s staggering fills her with remorse, though the truncated foreleg works as if it were really running and no blood oozes from the stump. As they come around again, the girl walks alongside, and January sees her face clearly. She’s plain, with mouse-colored hair and a tap-water complexion the gray dress does nothing for. When she tosses her head, January can see the filly in her.

A filly who does just that thing when they pass the dispenser again, snapping sideways with rolling eyes as if she means to grab the ring in her teeth. The pole restrains her, and she doesn’t come within three feet.

They pass the girl again, and this time January sees the man behind her. Hand in his pocket, fist clenched around something. The girl turns, a jerk of her head as startled as if somebody touched her shoulder, as if the pressure of his eyes hurt. She turns toward the doors, moving away, and like a viewer at a horror movie January wants to call after her—don’t go outside, don’t go through the door.

But the carousel carries her away again, and now she can’t make out the sound of the Wurlitzer at all. It’s lost under the cries of the animals, unless it’s become them.

The next time she comes around, she stands in the stirrups—wincing at her ankle, at the filly’s uneven gait—and reaches for the base-metal ring. Her fingers hook; she feels the tug; the ring pops free.

If she hoped it would be that simple, she is quickly disappointed. If anything, the carousel accelerates, a faster churning now. The neighs grow wilder. Something grazes her knee—a snap from the gray mare impaled beside her crippled filly. The filly snakes her head around and snaps back, and January leans as far to the outside as the stirrups allow.

Now there’s competition. Figures shimmer into the saddles of the elephant and the other ponies, but only on the inside ring. The carousel opposes her, her and the other January. Other fingers grope for rings, snap up one and then another, but they are all dull.

The cacophony persists. The carousel spins faster. The world wheels madly on.

From outside, she hears a single gunshot. Beneath her, the other January shies—but none of the people in the carousel shelter seem to hear.

She sets herself this time, leans out, her left foot solidly in the stirrup though her twisted ankle twinges. She braces with her right foot, aware that she’s reaching out too far and the mare might snap again. But there’s a brass ring in that dispenser somewhere, and if she doesn’t collect it, she doesn’t know how she’s getting off this carousel alive. The faces alongside are a blur now, the stained-glass seasons a colorful smear.

As they come up on the dispenser, she reaches over the filly’s neck. The cold ring brushes her fingertips. She snatches, sees bright metal, grabs again. Something sharp stabs up her right leg, pain like slamming it in a car door. It hauls, pulling her off balance, but she palms the ring she has already and her fingers hook the glittering circle of the next.

Momentum carries her forward, the ring snagged on her fingertips beginning to slide, the gray mare, teeth clenched in her calf muscle, hauling back.

January closes her hand before she loses the brass ring.

Silence falls, so sudden and hollow it makes her wonder briefly if she has been struck deaf. The carousel glides, slowing now.

–

Once the human element—motive, culpability, perception—enters the equation, it’s no longer so simple to trace a sequence of causality, to say—mechanistically, with confidence—here is the inciting event, and here is what caused that, and here is what caused that again.

We will never know why the finger pulls the trigger, even when it is our finger that tightens on yielding metal, our hand that jumps with the buck of the gun. We can speculate, but will never know.

It’s possible that her death was inevitable from the moment he followed her—tall and plain and smarting—from the shelter of the carousel, into the night where she died.

–

January limps away from the filly, the brass ring clutched in her palm. She has to twist and sidle to move between the animals, frozen now in contortions with reaching claws and gnashing teeth. Blood wells thick and artificial looking down her calf through the torn tights, skidding and squishing inside her Mary Jane.

Martin is waiting to catch her when she falls off the platform. The EMTs are there, gathered around Jeff, who is propped on his elbows telling jokes. The carousel operator sits beside him, head down, her hands pressed over her eyes.

Martin says to the EMTs, “I don’t know what happened. We were helping to clean up after the party, and the thing just turned itself on.”

January sits down gratefully on the plastic chair they bring. She extends her leg through the tear in her skirt. The EMT looks at it and clucks. “You’ll want to come to the ER.”

“Are the police on the way?”

The EMT nods, her blond ponytail bobbing. “They should be here in five minutes. Do you want to file a complaint?”

The carousel operator moans.

“No,” January says. “I want to report a murder. From about a hundred years ago.”

–

Firstly, he must have wanted to own her. Why else would he have found a way to keep her all this time?

As for what she wanted, what she dreamed as she rode (or ran) on the carousel that trapped her—to be seen, to be loved, to be free—as for what she wanted, no one ever asked her at all.

–

Elizabeth Bear was born on the same day as Frodo and Bilbo Baggins, and very nearly named after Peregrin Took. She is a recipient of the John W. Campbell, Sturgeon, Locus, and Hugo Awards. She has been nominated multiple times for the British Science Fiction Association Awards, and is a Philip K. Dick Award nominee. She currently lives in southern New England with a famous cat. Her hobbies include murdering inoffensive potted plants, ruining dinner, and falling off rock faces.

Her most recent books are a space opera, Chill, from Bantam Spectra, and a fantasy, By the Mountain Bound, from Tor.

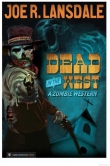

| DEAD SISTER |

| DEAD SISTER |

Joe R. Lansdale

–

I had my office window open, and the October wind was making my hair ruffle. I was turned sideways and had my feet up, cooling my heels on the edge of my desk, noticing my socks. Once the pattern on the socks had been clocks; now the designs were so thin and colorless, I could damn near see my ankles through them.

I was looking out the window, watching the town square from where I sat, three floors up, which was as high as anything went in Mud Creek. It seemed pretty busy down there for a town of only eight thousand. Even a couple of dogs were looking industrious, as if they were in a hurry to get somewhere and do something important. Chase a cat, bite a mailman, or bury a bone.

Me, I wasn’t working right then, and hadn’t in a while. For me, 1958 had not been a banner year.

I was about to get a bottle of cheap whiskey out of my desk drawer, when there was a knock on the door. I could see my name spelled backward on the pebbled glass, and beyond that a shadow that had a nice overall shape.

I said, “Come on in, the water’s fine.”

A blond woman wearing a little blue pill hat came in. She was the kind of dame if she walked real fast, she might set the walls on fire. She sat down in the client chair and crossed her legs and let her cool blue dress slide up so I could see her knees. She was wearing stockings so sheer, she might as well have not had any on. She lifted her head and stared at me with eyes that would make a monk set fire to his bible.

She was carrying a cute little purse that might hold a compact, a couple of quarters, and a pencil. She let it rest on her lap, laid her hand on it like it was a pet cat.

“Mr. Taylor? I was wondering if you could check on something for me?” she said.

“If it’s on your person, no charge.”

She smiled at me. “I heard you thought you were funny.”

“Not really, but I try the stuff out anyway. See how this one works for you. I get fifty a day plus expenses.”

“You might have to do some rough stuff.”

“How rough?” I said.

“I don’t know. I really don’t know what’s going on at all, but I think it may be someone who’s not quite right.”

“Did you talk to the police?” I asked.

She nodded. “They checked, watched for three nights. But nobody showed. Soon as they quit, it started over again.”

“Where did they watch, and what did they watch?”

“The graveyard. They were watching a grave. I could swear someone was digging it up at night.”

“You saw this?”

“If I saw it, I’d be sure, wouldn’t I?”

“You got me there,” I said.

“My sister, Susan. She died of something unexpected. Eighteen. Beautiful. One morning she’s feeling ill, and then the night comes, and she’s feeling worse, and the next day she’s dead. Just like that. She was buried in the Sweet Pine Cemetery, and I go each morning on my way to work to bring flowers to her grave. The ground never settled. I got the impression it was being worked over at night. That someone was digging there. That they were digging up my sister, or trying to.”

“That’s an odd thing to think.”

“The dirt was always disturbed,” she said. “The flowers from the day before were buried under the dirt. It didn’t seem right.”

“So, you want me to check the place out, see if that’s what’s going on?”

“The police were so noisy and so obvious I doubt they got a true view of things. No one would try with them there. They thought I was crazy. What I need is someone who can be discreet. I would go myself, but I might need someone with some muscle.”

“Yeah, you’re too nice a piece of chicken to be wandering a graveyard. It would be asking for trouble. Your sister’s name is Susan. What’s yours?”

“Oh, I didn’t tell you, did I? It’s Cathy. Cathy Carter. Can you start right away?”

“Soon as the money hits my palm.”

–

I probably didn’t need a .38 revolver to handle a grave robber, but you never know. So I brought it with me.

My plan was if there was someone actually there, to put the gun on him and make him lie down, tie him up, and haul him to the police. If he was digging up somebody’s sister, the country cops downtown might not let him make it to trial. He might end up with a warning shot in the back of the head. That happened, I could probably get over it.

Course, it could be more than one. That’s why the .38.

My take, though, was it was all hooey. Not that Cathy Carter didn’t believe it. She did. But my guess was the whole business was nothing more than her grieving imagination, or a dog or an armadillo digging around at night.

I decided to go out there and look at the place during the day. See if I thought there was any kind of monkey business going on.

Sweet Pines isn’t a pauper graveyard on the whole, but a lot of paupers are buried there, on the low back end near Coats Creek—actually on the other side of the graveyard fence. Even in death, they couldn’t get inside with the regular people. Outsiders to the end.

There’ve been graves there since the Civil War. A recent flood washed away a lot of headstones and broke the ground open and pushed some rotten bones and broken coffins around. It was all covered up in a heap with a dozer after that: sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, grandmas and grandpas, massed together in one big ditch for their final rest.

The fresher graves on the higher ground, inside the cemetery fence, were fine. That’s where Susan was buried.

I parked at the gate, which was a black ornamental thing with fence tops like spearheads. The fence was six feet high and went all around the cemetery. The front was a large, open area with a horseshoe sign over it that read in metal curlicues Sweet Pine Cemetery.

That was just in case you thought the headstones were for show.

Inside, I went where Cathy told me Susan was buried and found her grave easy enough. There was a stone marker with her name on it, and the dates of birth and death. The ground did look fresh dug. I bent down and looked close. There were scratches in the dirt, but they didn’t look like shovel work. There were a bunch of cigarette butts heel mashed into the ground near the grave.

I went over to a huge shade tree nearby and leaned on it, pulled out a stick of gum and chewed. It was comfortable under the tree, with the day being cool to begin with and the shadow of the limbs lying on the ground like spilled night. I chewed the gum and looked at the grave for a long time. I looked around and decided if there was anything to what Cathy had said, then the cops wouldn’t have seen it, or rather they would have discouraged any kind of grave-bothering soul from entering the cemetery in the first place. Those cigarette butts were the tip-off. My guess was they belonged to the cops, and they had stood not six feet from the grave, smoking, watching. Probably, like me, figuring it was all a pipe dream. Only thing was, I planned to give Cathy her whole dollar.

I drove back to the office and sat around there for a few hours, and then I went home and changed into some old duds, left my hat, grabbed a burger at Dairy Queen, and hustled my car back over to the cemetery. I drove by it and parked my heap about a half mile from the graveyard under a hickory-nut tree well off the main road and hoped no one would bother it.

I walked back to the cemetery and stood under the tree near Susan’s grave and looked up at it. There was a low limb, and I got hold of that and pulled myself up, and then climbed higher. The oak had very few leaves, but the limbs were big, and I found a place where there was a naturally scooped-out spot in the wood and laid down on that. It wasn’t comfortable, but I lay there anyway and chewed some gum and waited for the sun to set. That wouldn’t be long this time of year. By five thirty or six, the sun was gone and the night was up.

Night came, and I lay on the limb until my chest hurt. I got up and climbed higher, found a place where I could stand on a limb and wedge my ass in a fork in the tree. From there, I had a good look at the grave.

The dark was gathered around me like a blanket. To see me, you’d have to be looking for me. I took the gum out of my mouth and stuck it to the tree, and leaned back so that I was nestled firmly in the narrow fork. It was almost like an easy chair.

I could see the lights of the town from there, and I watched those for a while, and watched the headlights of cars in the distance. It was kind of hypnotic. Then I watched lightning bugs. A few mosquitoes came to visit, but it was a little cool for them, so they weren’t too bad.

I touched my coat pocket to make sure my .38 was in place, and it was. I had five shots. I didn’t figure I would need to shoot anyone, and if I did, I doubted it would take more than five shots.

I added up the hours I had invested in the case, my expenses, which were lunch and a few packs of chewing gum. This wasn’t the big score I was looking for, and I was beginning to feel silly, sitting in a tree waiting on someone to come along and dig around a grave.

I wanted to check my watch, but I couldn’t see the hands well enough, and though I had a little flashlight in my pocket, I didn’t want any light to give me away.

I twisted around and looked behind me. The fork in the tree split in the direction of the creek. It was the only direction I couldn’t see easily, so I checked it out for grins. All that mattered was I could see the grave and anything that came to it.

I’ll admit it: I wasn’t much of a sentry. After a while, I dozed.

What woke me was a scratching sound. When I came awake, I nearly fell out of the tree, not knowing where I was. By the time I had it figured, the sound was really loud. It was coming from the direction of the grave.

–

When I looked down I saw an animal digging at the grave, and then I realized it wasn’t a dog at all. I had only thought it was. It was a man in a long black jacket. He was bent over the grave and he was digging with his hands like a dog. He wasn’t throwing the dirt far, just mounding it up. While I had napped like a squirrel in a nest, he had dug all the way down to the coffin.

I pulled the gun from my pocket and yelled, “Hey, you down there. Leave that grave alone.”

The man wheeled then and looked up, and when he did, I got a glimpse of his face in the moonlight. It wasn’t a good glimpse, but it was enough to nearly cause me to fall out of the tree. The face was as white as a nun’s ass, and the eyes were way too bright, even if he was looking up into the moonlight; those eyes looked the way coyote eyes look staring out of the woods.

He hissed at me and went back to his work, popping the lid off the coffin like it was a cardboard box. It snapped free, and he reached inside and pulled out the body of a girl. Her hair was undone, and it was long and blond and fell over the dirty white slip she was wearing. He pulled her out of there before I could get down from the tree with the gun. The air was full of the stink of death. Susan’s body, I guessed.

By the time I hit the ground, he had the body thrown over his shoulder, and he was running across the graveyard, between the stones, like a goddamn deer. I ran after him with my gun, yelling for him to stop. He was really moving. I saw him jump one of the tall upright grave stones like it was lying down and land so light he seemed like crepe paper floating down.

Now that he was running, not crouching and digging like a dog, I could tell more about his body type. He was a long, skinny guy with stringy white hair and the long black coat that spread out around him like the wings of a roach. The girl bounced across his shoulder as though she was nothing more than a bag of dry laundry.

I chased him to the back fence, puffing all the way, and then he did something that couldn’t be done. He sprang and leaped over that spear-tipped fence with Susan’s body thrown over his shoulder, hit the ground running and darted down to the creek, jumped it, and ran off between the trees and into the shadows and out of my sight.

That fence was easily six feet high.

–

I started to drive over to Cathy’s place. I had her address. But I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t go there and I didn’t go home, which was a dingy apartment. I went to the office, which was slightly better, and got the bottle out of the drawer, along with my glass, and poured myself a shot of my medicine. It wasn’t a cure, but it was better than nothing. I liked it so much I poured another.

I went to the window with my fresh-filled glass and looked out. The night looked like the night and the moon looked like the moon and the street looked like the street. I held my hand up in front of me. Nope. That was my hand, and it had a glass of cheap whiskey in it. I wasn’t dreaming, and to the best of my knowledge I wasn’t crazy.

I finished off the drink. I thought I should have taken a shot at him. But I hadn’t because of Susan’s body. She wouldn’t mind a bullet in the head, but I didn’t want to have to explain that to her sister if I accidentally hit her.