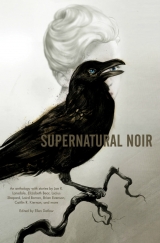

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“So what? You thought I was gonna plead for my life? You thought maybe I was gonna get down on my knees for you and beg? Is that how you like it? Maybe you’re just steamed cause I was on top—”

“Shut up, Ellen. You don’t get to talk yourself out of this mess. It’s a done deal. You tried to give Auntie H. the high hat.”

“And you honestly think she’s on the level? You think you pop me and she lets you off the hook, like nothing happened?”

“I do,” I said. And maybe it wasn’t as simple as that, but I wasn’t exactly lying, either. I needed to believe Harpootlian, the same way old women need to believe in the infinite compassion of the little baby Jesus and Mother Mary. Same way poor kids need to believe in the inexplicable generosity of Popeye the Sailor and Santa Claus.

“It didn’t have to be this way,” she said.

“I didn’t dig your grave, Ellen. I’m just the sap left holding the shovel.”

And she smiled that smug smile of hers and said, “I get it now, what Auntie H. sees in you. And it’s not your knack for finding shit that doesn’t want to be found. It’s not that at all.”

“Is this a guessing game,” I asked, “or do you have something to say?”

“No, I think I’m finished,” she replied. “In fact, I think I’m done for. So let’s get this over with. By the way, how many women have you killed?”

“You played me,” I said again.

“Takes two to make a sucker, Nat,” she smiled.

Me, I don’t even remember pulling the trigger. Just the sound of the gunshot, louder than thunder.

–

Caitlнn R. Kiernan is the author of seven novels, including the award-winning Threshold and, most recently, Daughter of Hounds and The Red Tree. Her short fiction has been collected in Tales of Pain and Wonder; From Weird and Distant Shores; To Charles Fort, with Love; Alabaster; A Is for Alien; and, most recently, The Ammonite Violin & Others. Her erotica has been collected in two volumes, Frog Toes and Tentacles and Tales from the Woeful Platypus. She is currently beginning work on her eighth novel. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

| DREAMER OF THE DAY |

| DREAMER OF THE DAY |

Nick Mamatas

–

Hallway, just narrow enough for two. Tin ceiling, haze in the air. It’s a railroad apartment, three floors up. A pile of old toys and junk—half a bicycle, plastic playhouse all stained and grimy Day-Glo, empty wrinkled cardboard boxes, coils of cable—blocks the back door. By the front door, a small table littered with envelopes. Bills, looks like. Cellophane windows and a name over and over, in all caps.

So you pick a bill, Paul says.

Any one? Lil asks.

That’s the fee. Pick a bill and pay it. This operator, he doesn’t leave the house, he’s not on anyone’s payroll. He puts his bills out here. You want to hire him, you pick out a bill and pay it. This is how he lives.

Yeah, but . . . She bites her lower lip. Licks it. She’s a real lip licker. So what if I take this one?

She taps a Verizon envelope. Her finger is fat on it, like crushing a bit.

Maybe it’s fifty bucks. Maybe he calls lots of 900 numbers, she says. Is that enough, though? If he’s as good as you say he is—

He’s the best.

It’ll look like an accident?

No.

The finger comes off the envelope. No?

It’ll be an accident, he says.

Eyes roll. Whatever, she says. How can he live like this? I mean, if people can pick any bill they like and pay it, why would anyone bother to pay his rent when they could pay some fifty-dollar phone bill? The West Village, I mean. Jesus.

Rent control. It’s not that bad. He’s been here for a long time, Paul says. Then he puts his hands to his mouth, cupping them. Woom woommm wommm he plays, like a sad trumpet. Then he sings two words. Twi-light time. You know it? Paul asks.

She looks at him.

Glenn Miller, Paul says. Plain as day.

A cheek inches up, dragging her lips into a smirk. Another lick.

“Stardust.” Google it or something. Glenn Miller vanished over the English Channel. He and his army band were flying into liberated Paris to play and . . . He lifts his palms in a shrug.

And they crashed and drowned?

No, just vanished. Not a trace of him, or the band, or the plane. That was his first hit, they say, Paul says. That’s how old this guy is.

I thought you said this guy makes his hits look like accidents, not like episodes of The X-Files, she says.

We can leave right now, if you like. If you’re not impressed. If you don’t want to pick up a bill and take it downstairs to the check-cashing place and pay his electricity or his cable or whatever the hell else, Paul says. If you don’t want to give him three hundred bucks for his rent this month. If you want to try somebody else who might cut your husband’s brakes or shoot him in the fucking face for twenty times the money. Yeah, that won’t be traced back to you. Have you even practiced crying in the mirror, Merry Widow?

Tears well up in her eyes. She stands up straight, then her spine wilts. Waterworks. The man makes to reach out for her, not thinking. All autonomic nerves, limbs jerking toward the brunette Lil like she needs saving.

All right, all right, you’re good, Paul says.

Lil reaches for an envelope, flashes that it’s addressed from Marolda Properties, and puts it in her purse. Now what, she says.

We wait.

How about we knock? She raises a tiny fist.

I wouldn’t.

Can we smoke?

No . . . but yes, he says. He reaches into his suit pocket and pulls out a silver-on-bronze case, flicking it open and offering her a cigarette.

From crimped lips: no light?

He produces a lighter, flicks it open too. Matches the case. The cherry blooms, and the door unlocks.

Put those nasty things out, the Dreamer of the Day says. You’ll kill us all. The Dreamer’s not a striking man. He couldn’t get a job standing on the lip of a grave on a soundstage, to stare down at the lens of a video camera. A little pudgy, skin like defrosting chicken. His undershirt is yellowed, his eyes an unremarkable brown. Hair a bundt cake around the back of his head. Lil didn’t have lunch today. She couldn’t eat.

The apartment is all newspapers, at first. Then she sees other things—boxes stuffed with green-and-white-striped printouts, old black-screened TVs, dusty Easter baskets, a pile of shoes. The Dreamer leads them like there’s a choice—the kitchen is piles up to the Dreamer’s eyebrows except for the path carved out from force of habit, and the living room is newspapers and magazines avalanching from sagging couches, and the bedroom is just piles of old-man clothes. Hats and green suit jackets and shirtsleeves sticking out like quake victims who didn’t quite pull themselves from fissures. The man has to stand sideways and sidle after the Dreamer. The woman fits, but barely, her elbows tight.

Lil doesn’t smell a thing except old man: lavender and urine.

The bedroom—magazines she’s never seen before, filing cabinets on their sides across a twin bed, a rain of hanging plants. A patch of mattress ticking, bald and empty—the Dreamer takes a seat there. Paul finds a little bench, sweeps it free of old coffee cans and pipe cleaners, and sits. There’s room for her but she stands. The Dreamer reaches and there’s an audible click. A big cabinet-sized television set, framed in trash. Knobs. Black and white, but a nest of cables snaking up from it to a hole punched through the tin ceiling. Her former show is on. The Cove of Love.

Is this some kind of setup? Lil asks. Is this some kind of joke?

The Dreamer says, I like this show. You were good on it.

I don’t watch it anymore, she says.

Paul pats the bench. She sits.

Sotto voce, Paul says, We really should wait for a commercial.

On the screen there’s a man. Old, with silver hair. In business wear, but he means business too. Sleeves rolled up. Suspenders, thick and brown. A pile of dirt, a shovel. The sky behind him is swirls of paint, normally bursting with red and purple (the woman knows that matte painting well), but on the Dreamer’s television screen it’s a sea of gray. The man picks up the shovel and begins to dig. A voice, tinny and distant, begs him to stop. It’s her voice.

That’s a clip from three years ago, she says. Paul hisses at her. She nudges him with her elbow. The bench wobbles under them.

Yes, the Dreamer says. When Savannah was in that old bomb shelter where the gang had her cornered, and they decided to lock her in. I remember those words, that tone. Tell me something.

Yes?

Do you have a lot of the same outfit?

Excuse me?

When you’re doing something like that. Does wardrobe take back whatever you’re wearing every day and clean it, then dirty it up again so it’ll match, and you wear that suit every day? Or is there a rack full of identical pantsuits, with identical tears and identical smudges and burn marks, and you wear a new one every day? You were in that bomb shelter for three months, ten minutes a day.

They have a few outfits. We have girls who take digital pictures and they try to match the amount of dishevelment, Lil says. I think we had three of that outfit for that story arc.

That’s why I like The Cove of Love. I can tell that the director really cares about the show, the Dreamer of the Day says. The other soaps don’t even try anymore.

A commercial for vegetable oil. A world where people in a room can look out the windows, where women stare off into space and hold up bottles and confide in the universe that some things are tastier than others.

Why’d you bring her here, Ron? the Dreamer asks.

I want my husband—the words stick in her throat.

Ron.

Ron opens his mouth. She is tired of being married to her husband.

The Dreamer turns to look at her, to look at Ron too.

Aren’t you a women’s libber?

Lil laughs at that. Who even says women’s libber anymore?

You can get a divorce.

Maybe he doesn’t deserve a divorce. You want the gory details? Paul told me you’re a no-questions-asked kind of guy.

Ron, the Dreamer says.

She looks at the man next to her.

Here, he says, I’m Ron.

Savannah—

Call me Lil, she says.

Savannah, the Dreamer repeats, I am a no-questions-asked kind of guy. I can’t say I like women’s libbers very much. I don’t care why you want your husband dead, but women like you, Savannah, you want to talk about it.

I’m not a woman like Savannah, she says. That was a character I played on the show.

And the show starts again. There’s a hospital. A man turns on his heel and walks off frame. A close-up of a woman’s face. All redheads and blonds look alike. The Dreamer tells them the character’s name is Trista and that she has something horrible inside her. Then two kids bouncing on a couch, too enthusiastic when the man who meant business walks in after burying Savannah alive. A restaurant scene is next, the rhubarbrhubarb of the crowd scene like the Dreamer’s labored breaths. Then a commercial for people who want to fill a bag with gold and mail it away.

The Dreamer says, Ron, go downstairs and get us some coffees. Ron gets up and squeezes past the rubbish into the next room.

Lil puts her hand in her hair, combing it with her fingers. I want my husband dead because he’s been cheating on me.

Bullshit. Pardon my French. I don’t get many female visitors. I’m sure that doesn’t surprise you. I know I haven’t kept up my apartment. I’m embarrassed. Ron should have told me you were coming. That you were coming. We could have met in the diner.

I thought you never leave.

Maybe I’d make an exception, the Dreamer says. He looks at Lil. His dentures are heavy like two rows of tombstones.

He is cheating on me. This is his third or fourth little whore.

That’s not why you want him dead. If you wanted him dead, you would have put out a hit two or three whores ago.

I used to have a career, something to occupy my own days. Now I’m home all day, or at the gym. I can feel her sweat on the sheets of my own bed when I lay down at night. It’s humiliating.

Humiliating, the Dreamer echoes.

I don’t know if I’ll ever get another role. I’m forty-one years old. I never crossed over to movies, not even to prime time.

You’re not the bitch-goddess type, the Dreamer says. Not the part for you.

I want to know that there’s something more to the world than what I’ve already lived through.

The Dreamer extends a finger and turns off the television set. A single pixel burns in the middle of the screen.

There’s a lot more. Worlds within worlds. You are having an affair with Ron.

The irony doesn’t escape me, Lil says.

You ain’t escapin’ it either, the Dreamer says.

What?

Ron told me that you were together. I feel for him. His wife, the big C. In her breasts, and now her brain. But it’s not just that—he loves you, more than he ever loved her.

He’s a good man, Lil says.

What’s your husband’s name?

Whatever happened to no questions asked?

The Dreamer smiles. I do have to ask one question. Not a personal one. Well, it’s about preferences, not information.

Answer mine first, Lil says.

Anything for you, Miss Savannah.

Why do they call you the Dreamer of the Day?

All men dream, but not equally, the Dreamer says. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes to make it possible.

That’s beautiful.

That’s T. E. Lawrence.

Who?

The Dreamer of the Day shivers, visibly disgusted. Finally, he lets . . . of Arabia extrude from his mouth like sludge. And you got two questions out of me, Savannah. More than anyone ever has. I have a weakness for you.

I apologize, Lil says. I’ll collect another envelope from the foyer on my way out. She says foyer like a Frenchwoman. What’s your question?

Kill him fast or kill him slow?

Kill him slow.

The Dreamer gets up and leaves the room. Lil hears some clatter in the kitchen and gets up. The Dreamer has cleared off the stove. He has a teakettle out. She almost trips over the junk on the floor.

Pau—uh, Ron. He’s getting coffees from the diner.

Ron’s not getting us any fucking coffee, the Dreamer says, gravel in his teeth. Paul’s not getting coffees. He puts his hands on the stove, a little electric number, squeezes his fingers in the gaps between counter and stovetop on either side, and gives it all a shake. A red light blinks to life.

No apologies for your French this time, monsieur?

This is how it’s gonna go, the Dreamer of the Day says. He looks up and off to the side, at some random piece of paper up atop a teetering pile in the living room. Ron’s down at the diner, see. He knows the one. It used to be Greek; it’s Russian now. Your husband’s fourth little whore is there. Blond, milkmaid type. Her upper lip curls when she smiles. He likes that kind of thing. You can do it too.

She can, yes. She does, Pavlovian. Close-ups, she says. You’ve seen the show.

Well, it just so happens that your husband is in the diner too, see? He likes to watch the girl lean over the Formica for tips. He likes to count the seconds other men keep their hands on her ass while she takes their orders. Then he likes to take her up to your home, up to Valhalla on the Metro North so he doesn’t have to drive, doesn’t have to keep his hands on the wheel.

Valhalla. That’s on my Wikipedia page. You probably have a computer around here somewhere.

The Dreamer starts rummaging through a cabinet for a cup. He finds one, waves it hooked around his finger, and then finds a second. This on your Wikipedia page? he asks. Your boyfriend Paul Osorio is connected. How you think he knows me? He’s packing. He sees your husband and is overcome. He pulls out his gun.

Paul doesn’t carry a gun. He’s a good man.

He knows the Dreamer of the Day. I don’t know any good men. I don’t meet them in my line of work. No good women either. What did he tell you? That he knew a guy who knew a guy who knew someone who could help you? He is a guy. He’d have done it himself, if you’d asked him, but why would you ask him? He’s a good man.

Mister, I think I’m going to meet Paul downstairs. I’ll get you some help—my sister is a social worker. You don’t have to live like this. There are nice places. You won’t be lonely either.

The teakettle screams. You don’t want to go down there, the Dreamer says. Paul’s already put a bullet in your husband. He aimed for the head but missed because the whore’s a sharpie. Paul got a faceful of hot coffee the second she saw the gun. Right in the eyes. He’s not going to see out of his left anymore. That face—second– and third-degree burns. St. Vincent’s isn’t that far away. Both of them will make it to the ER.

My husban—

The chest. Bullet just misses the heart. But you said you wanted it slow, so you get it. He bleeds, but he lives. You can go see him later tonight if you want. Take in a movie. Buy yourself a nice dinner. Nine p.m. Visiting hours will be over, but they’ll let you in. The night shift, they’re all fans. You’ll cry like you did in court when the government took your Chinese baby away.

That wasn’t me. That was a character.

They were your tears, the Dreamer of the Day says. That’ll get you in. Go see him. You’ll think the staph will have come from here. That you’re the carrier, that you infected him.

He pours two cups of tea. He hands one to Lil. She takes it but doesn’t drink.

This is the most disgusting place you’ve ever set foot in, he says matter-of-factly. So when your husband gets the MRSA, you’ll think it’s your fault. It’ll get in his blood nice and slow. It’ll take weeks for him to die. He’ll cry even better than you, demand that you visit him every day. Get a hotel room so you can spend all day by his side. He’ll forget the whore entirely, and she’ll be sent back to Moscow till the heat is off. You’ll sneak down to the burn ward to see Paul twice, three times. Then forget it. It won’t matter though.

Why won’t it? she asks. She passes the cup from hand to hand. There’s no place to put it down.

His face will be ruined, but so will your husband’s. The MRSA will do a number on his skin. Boils worthy of Job. Kill him slow. He’ll lose half his nose. Three weeks of rats in the veins.

Lil throws the content of her teacup at the Dreamer of the Day, but he’s ready. He swipes an old New York Post off the countertop and holds it up. The tea splatters all over another disgraced governor in black and white and red.

The Dreamer drops the paper, steps on it as he walks past Lil. Show’s over, he says. Go home. You’ll see.

She follows him back to the bedroom. You crazy old man, she says. What the hell? Did you put Paul up to this? Did he put you up to this? What kind of freak show are you two lunatics running here? Christ, talk about far fetched. I’ve met some real winners, some deranged fans, but you, you are a fucking fruitcake—

The Dreamer grabs a great handful of old suits and tosses them on the white tongue of the bed on which he’d sat. The back door of the railroad apartment. He opens it and walks out without a word. Where are you going! You can’t leave! she demands. The door slams shut. Lil rushes to the door, tries the knob. It’s unlocked, but she has to push, not pull. All the trash and boxes bar the way. She can’t squeeze her pinky through the crack of the door for the rubbish. Lil grabs her purse from the little bench, runs through the apartment on tiptoes, sideways along the narrow path through the piles of garbage, and hits the hallway through the front entrance.

No Dreamer. Lil looks down the well of the staircase. No Dreamer. He’s an old, slow man. He couldn’t have made it outside in time. She’s on the second floor; there are no first-floor apartments he could have ducked into. Lil stomps down the steps and walks outside to a dusk painted red and blue from the lights of ambulances and a black and white. A radio crackles. A shrieking, thrashing blond held inches over the sidewalk by a pair of cops gets shoved into the back seat of the cop car. Then, gurneys.

–

Lil can’t see her husband. He’s in emergency surgery. Paul she doesn’t dare ask after, not when she sees two men in tank-shaped suits in the waiting area very patiently not reading the newspapers open in their hands. She doesn’t want to go all the way up to Grand Central. She doesn’t want to say to the Metro North ticket clerk behind those bars of bronze, “One-way to Valhalla.” She takes in a movie. Cries through it. It’s about someone with cancer. A real tearjerker. She can taste the hospital onscreen. Lil orders a nice dinner in a little place down on Greenwich Street, where the grid of the city collapses against the shore of the Hudson River. Doesn’t eat it. Tips 50 percent for some privacy. Indigo skies go gray. Nine o’clock, she’s crying in the lobby of St. Vincent’s. Not for her husband. Not for Paul. But her husband, he’s the one she decides to see.

Lil washes her hands at the restaurant. Again in the ladies’ restroom. She takes her husband’s hand now because he’s unconscious, breathing hard as though deep in his still body he’s running from somebody. She pulls her hand back, but it’s too late.

–

Nick Mamatas is the author of three novels—Move Under Ground, Under My Roof, and Sensation—and of over sixty short stories, many of which were collected in You Might Sleep . . . Nick’s fiction has been thrice nominated for the Bram Stoker Award, and as coeditor of Clarkesworld, he’s been nominated for the Hugo and World Fantasy Awards.

| IN PARIS, IN THE MOUTH OF KRONOS |

| IN PARIS, IN THE MOUTH OF KRONOS |

John Langan

–

I

“You know how much they want for a Coke?”

“How much?” Vasquez said.

“Five euros. Can you believe that?”

Vasquez shrugged. She knew the gesture would irritate Buchanan, who took an almost pathological delight in complaining about everything in Paris, from the lack of air conditioning on the train ride in from de Gaulle to their narrow hotel rooms, but they had an expense account, after all, and however modest it was, she was sure a five-euro Coke would not deplete it. She didn’t imagine the professionals sat around fretting over the cost of their sodas.

To her left, the broad Avenue de la Bourdonnais was surprisingly quiet; to her right, the interior of the restaurant was a din of languages: English, mainly, with German, Spanish, Italian, and even a little French mixed in. In front of and behind her, the rest of the sidewalk tables were occupied by an almost even balance of old men reading newspapers and youngish couples wearing sunglasses. Late-afternoon sunlight washed over her surroundings like a spill of white paint, lightening everything several shades, reducing the low buildings across the avenue to hazy rectangles. When their snack was done, she would have to return to one of the souvenir shops they had passed on the walk here and buy a pair of sunglasses. Another expense for Buchanan to complain about.

“M’sieu? Madame?” Their waiter, surprisingly middle aged, had returned. “Vous кtes—”

“You speak English,” Buchanan said.

“But of course,” the waiter said. “You are ready with your order?”

“I’ll have a cheeseburger,” Buchanan said. “Medium rare. And a Coke,” he added with a grimace.

“Very good,” the waiter said. “And for madame?”

“Je voudrais un crкpe au chocolat,” Vasquez said, “et un cafй au lait.”

The waiter’s expression did not change. “Trиs bien, madame. Merзi,” he said as Vasquez passed him their menus.

“A cheeseburger?” she said once he had returned inside the restaurant.

“What?” Buchanan said.

“Never mind.”

“I like cheeseburgers. What’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing. It’s fine.”

“Just because I don’t want to eat some kind of French food—ooh, un crкpe, s’il vous plaоt.”

“All this,” Vasquez nodded at their surroundings, “it’s lost on you, isn’t it?”

“We aren’t here for all this,” Buchanan said. “We’re here for Mr. White.”

Despite herself, Vasquez flinched. “Why don’t you speak a little louder? I’m not sure everyone inside the cafй heard.”

“You think they know what we’re talking about?”

“That’s not the point.”

“Oh? What is?”

“Operational integrity.”

“Wow. You pick that up from the Bourne movies?”

“One person overhears something they don’t like, opens their cell phone, and calls the cops—”

“And it’s all a big misunderstanding, officers, we were talking about movies, ha ha.”

“—and the time we lose smoothing things over with them completely fucks up Plowman’s schedule.”

“Stop worrying,” Buchanan said, but Vasquez was pleased to see his face blanch at the prospect of Plowman’s displeasure.

For a few moments, Vasquez leaned back in her chair and closed her eyes, the sun lighting the inside of her lids crimson. I’m here, she thought, the city’s presence a pressure at the base of her skull, not unlike what she’d felt patrolling the streets of Bagram, but less unpleasant. Buchanan said, “So you’ve been here before.”

“What?” Brightness overwhelmed her vision, simplified Buchanan to a dark silhouette in a baseball cap.

“You parlez the franзais pretty well. I figure you must’ve spent some time—what? In college? Some kind of study-abroad deal?”

“Nope,” Vasquez said.

“Nope, what?”

“I’ve never been to Paris. Hell, before I enlisted, the farthest I’d ever been from home was the class trip to Washington senior year.”

“You’re shittin’ me.”

“Uh-uh. Don’t get me wrong: I wanted to see Paris, London—everything. But the money—the money wasn’t there. The closest I came to all this were the movies in Madame Antosca’s French 4 class. It was one of the reasons I joined up: I figured I’d see the world and let the army pay for it.”

“How’d that work out for you?”

“We’re here, aren’t we?”

“Not because of the army.”

“No, precisely because of the army. Well,” she said, “them and the spooks.”

“You still think Mr.—oh, sorry—You-Know-Who was CIA?”

Frowning, Vasquez lowered her voice. “Who knows? I’m not even sure he was one of ours. That accent . . . He could’ve been working for the Brits, or the Aussies. He could’ve been Russian, back in town to settle a few scores. Wherever he picked up his pronunciation, dude was not regular military.”

“Be funny if he was on Stillwater’s payroll.”

“Hysterical,” Vasquez said. “What about you?”

“What about me?”

“I assume this is your first trip to Paris.”

“And there’s where you would be wrong.”

“Now you’re shittin’ me.”

“Why, because I ordered a cheeseburger and a Coke?”

“Among other things, yeah.”

“My senior-class trip was a week in Paris and Amsterdam. In college, the end of my sophomore year, my parents took me to France for a month.” At what she knew must be the look on her face, Buchanan added, “It was an attempt at breaking up the relationship I was in at the time.”

“It’s not that. I’m trying to process the thought of you in college.”

“Wow, anyone ever tell you what a laugh riot you are?”

“Did it work—your parents’ plan?”

Buchanan shook his head. “The second I was back in the US, I knocked her up. We were married by the end of the summer.”

“How romantic.”

“Hey.” Buchanan shrugged.

“That why you enlisted, support your new family?”

“More or less. Heidi’s dad owned a bunch of McDonald’s; for the first six months of our marriage, I tried to assistant manage one of them.”

“With your people skills, that must have been a match made in heaven.”

The retort forming on Buchanan’s lips was cut short by the reappearance of their waiter, encumbered with their drinks and their food. He set their plates before them with a madame and m’sieu, then, as he was distributing their drinks, said, “Everything is okay? Зa va?”

“Oui,” Vasquez said. “C’est bon. Merзi.”

With the slightest of bows, the waiter left them to their food.

While Buchanan worked his hands around his cheeseburger, Vasquez said, “I don’t think I realized you were married.”

“Were,” Buchanan said. “She wasn’t happy about my deploying in the first place, and when the shit hit the fan . . .” He bit into the burger. Through a mouthful of bun and meat, he said, “The court-martial was the excuse she needed. Couldn’t handle the shame, she said. The humiliation of being married to one of the guards who’d tortured an innocent man to death. What kind of role model would I be for our son?

“I tried—I tried to tell her it wasn’t like that. It wasn’t that—you know what I’m talking about.”

Vasquez studied her neatly folded crкpe. “Yeah.” Mr. White had favored a flint knife for what he called the delicate work.

“If that’s what she wants, fine, fuck her. But she made it so I can’t see my son. The second she decided we were splitting up, there was her dad with money for a lawyer. I get a call from this asshole—this is right in the middle of the court-martial—and he tells me Heidi’s filing for divorce—no surprise—and they’re going to make it easy for me: no alimony, no child support, nothing. The only catch is, I have to sign away all my rights to Sam. If I don’t, they’re fully prepared to go to court, and how do I like my chances in front of a judge? What choice did I have?”

Vasquez tasted her coffee. She saw her mother, holding open the front door for her, unable to meet her eyes.

“Bad enough about that poor bastard who died—what was his name? If there’s one thing you’d think I’d know . . .”

“Mahbub Ali,” Vasquez said. What kind of a person are you? her father had shouted. What kind of person is part of such things?

“Mahbub Ali,” Buchanan said. “Bad enough what happened to him; I just wish I’d known what was happening to the rest of us, as well.”

They ate the rest of their meal in silence. When the waiter returned to ask if they wanted dessert, they declined.

–

II

Vasquez had compiled a list of reasons for crossing the avenue and walking to the Eiffel Tower, from It’s an open, crowded space—it’s a better place to review the plan’s details, to I want to see the fucking Eiffel Tower once before I die, okay? But Buchanan agreed to her proposal without argument; nor did he complain about the fifteen euros she spent on a pair of sunglasses on the walk there. Did she need to ask to know he was back in the concrete room they’d called the Closet, its air full of the stink of fear and piss?

Herself, she was doing her best not to think about the chamber under the prison’s subbasement Just-Call-Me-Bill had taken her to. This was maybe a week after the tall, portly man she knew for a fact was CIA had started spending every waking moment with Mr. White. Vasquez had followed Bill down poured-concrete stairs that led from the labyrinth of the basement and its handful of high-value captives in their scattered cells (not to mention the Closet, whose precise location she’d been unable to fix) to the subbasement, where he had clicked on the large yellow flashlight he was carrying. Its beam had ranged over brick walls, an assortment of junk (some of it Soviet-era aircraft parts, some of it tools to repair those parts, some of it more recent: stacks of toilet paper, boxes of plastic cutlery, a pair of hospital gurneys). They had made their way through that place to a low doorway that opened on carved stone steps whose curved surfaces testified to the passage of generations of feet. All the time, Just-Call-Me-Bill had been talking, lecturing, detailing the history of the prison, from its time as a repair center for the aircraft the Soviets flew in and out of here, until some KGB officer decided the building was perfect for housing prisoners, a change everyone who subsequently held possession of it had maintained. Vasquez had struggled to pay attention, especially as they had descended the last set of stairs and the air grew warm, moist, the rock to either side of her damp. Before, the CIA operative was saying. Oh, before. Did you know a detachment of Alexander the Great’s army stopped here? One man returned.