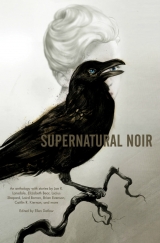

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

I laid down on the couch for a little while, and the whiskey helped me sleep, but when I came awake, and turned on the light and looked at my watch, it was just then midnight.

I got my hat and my gun and my car keys off the desk, went down to my car, and drove back to the cemetery.

–

I didn’t park down from the place this time. I drove through the horseshoe opening and drove down as close as I could get to the grave. I got out and looked around, hoping I wouldn’t see the man in the long coat, and hoping in another way I would.

I got my gun from my pocket and held it down by my side, and walked over to the grave. It was covered up, patted down. The air still held that stench from before. Less of it, but it still lingered, and I had this odd feeling it wasn’t the stink of Susan’s body after all. It was that man. It was his stink. I felt sure of it, but there was no reasoning as to why I thought that. Call it instinct. I looked down at the grave. It was closed up.

The hair on the back of my neck stood up like I had been shot with a quiverful of little arrows.

Looking every which way as I went, I made it back to the car and got inside and locked all the doors and started it up, and drove back to town and over to Cathy’s place.

–

We were in her little front room sitting on the couch. There was coffee in cups on saucers sitting on the coffee table. I sipped mine and tried to do it so my hand didn’t shake.

“So now you believe me,” she said.

“But I don’t know anyone else will. We tell the cops this, we’ll both be in the booby hatch.”

“He took her body?”

I nodded.

“Weren’t you supposed to stop him?”

“I actually didn’t think that was going to come up. But I couldn’t stop him. He didn’t look like much, but he was fast, and to leap like that, he had to be strong. He carried your sister’s body like it was nothing.”

“My heavens, what could he want with her?”

I had an idea, considering she only had on a slip. That meant he’d been there before, undressed her, and put her back without her burial clothes. But Cathy, she was on the same page.

“Now someone has her body,” she said, “and they’re doing who knows what to her . . . Oh, Jesus. This is like a nightmare. Listen, you’ve got to take me out there.”

“You don’t want to do that,” I said.

“Yes I do, Mr. Taylor. That’s exactly what I want to do. And if you won’t do it, I’ll go anyway.”

She started to cry and leaned into me. I held her. I figured part of it was real and part of it was like the way she showed me her legs; she’d had practice getting her way with men.

–

I drove her over there.

It was just about daybreak when we arrived. I drove through the gate and parked near the grave again. I saw that fellow, even if he was carrying two dead blonds on his shoulders, I was going to take a shot at him. Maybe two. That didn’t work, I was going to try and run over him with my car.

Cathy stood over the grave. There was still a faint aroma of the stink from before.

Cathy said, “So he came back and filled it in while you were at your office, doing—what did you say—having a drink?”

“Two, actually.”

“If you hadn’t done that, he would have come back and you would have seen him.”

“No reason for me to think he’d come back. I just came to look again to make sure I wasn’t crazy.”

As the sun came up, we walked across the cemetery, me tracing the path the man had taken as he ran. When I got to the fence, I looked to see if there was anything he could have jumped up on or used as a springboard to get over. There wasn’t.

We went back to the car and I drove us around on the right side near the back of the cemetery. I had to park well before we got to the creek. It was muddy back there where the creek rose, and there were boot prints in the mud from the flooding. The flood had made everything a bog.

I looked at the fence. Six feet tall, and he had landed some ten feet from the fence on this side. That wasn’t possible, but I had seen him do it, and now I was looking at what had to be his boot tracks.

I followed the prints down to the creek, where he had jumped across. It was all I could do to stay on my feet, as it was such a slick path to follow, but he had gone over it as sure-footedly as a goat.

Cathy came with me. I told her to go back, but she wouldn’t listen. We walked along the edge of the creek until we found a narrow spot, and I helped her cross over. The tracks played out when the mud played out. As we went up a little rise, the trees thickened even more and the land became drier. Finally we came to a nearly open clearing. There were a few trees growing there, and they were growing up close to an old sawmill. One side of it had fallen down, and there was an ancient pile of blackened sawdust mounded up on the other where it had been dumped from the mill and rotted by the weather.

We went inside. The floorboards creaked, and the whole place, large as it was, shifted as we walked.

“Come on,” I said. “Before we fall all the way to hell.”

On the way back, as we crossed the creek, I saw something snagged on a little limb. I bent over and looked at it. It stank of that smell I had smelled in the graveyard. I got out my handkerchief and folded the handkerchief around it and put it in my pocket.

Back in the car, driving to town, Cathy said, “It isn’t just some kook, is it?”

“Some kook couldn’t have jumped a fence like that, especially with a body thrown over its shoulder. It couldn’t have gone across that mud and over that creek like it did. It has to be something else.”

“What does ‘something else’ mean?” Cathy said.

“I don’t know,” I said.

We parked out near the edge of town, and I took the handkerchief out and unfolded it. The smell was intense.

“Throw it away,” Cathy said.

“I will, but first, you tell me what it is.”

She leaned over, wrinkled her pretty nose. “It’s a piece of cloth with meat on it.”

“Rotting flesh,” I said. “The cloth goes with the man’s jacket, the man I saw with Susan’s body. Nobody has flesh like this if they’re alive.”

“Could it be from Susan?” she asked.

“Anything is possible, but this is stuck to the inside of the cloth. I think it came off him.”

–

In town, I bought a shovel at the hardware store, and then we drove back to the cemetery. I parked so that I thought the car might block what I was doing a little, and I told Cathy to keep watch. It was broad daylight, and I hoped I looked like a gravedigger and not a grave robber.

She said, “You’re going to dig up the grave?”

“Dang tootin’,” I said, and I went at it.

Cathy didn’t like it much, but she didn’t stop me. She was as curious as I was. It didn’t take long because the dirt was soft, the digging was easy. I got down to the coffin, scraped the dirt off, and opened it with the tip of the shovel. It was a heavy lid, and it was hard to do. It made me think of how easily the man in the coat had lifted it.

Susan was in there. She looked very fresh and she didn’t smell. There was only that musty smell you get from slightly damp earth. She had on the slip, and the rest of her clothes were folded under her head. Her shoes were arranged at her feet.

“Jesus,” Cathy said. “She looks so alive. So fair. I understand why someone would dig her up, but why would they bring her back?”

“I’m not sure, but I think the best thing to do is go see my mother.”

–

My mother is the town librarian. She’s one of those that believe in astrology, ESP, little green men from Mars, ghosts, a balanced budget, you name it. And she knows about that stuff. I grew up with it, and it never appealed to me. Like my dad, I was a hardheaded realist. And at some point, my mother had been too much for him. They separated. He lives in Hoboken with a showgirl, far from East Texas. He’s been there so long he might as well be a Yankee himself.

The library was nearly empty, and as always, quiet as God’s own secrets. My mother ran a tight ship. She saw me when I came in and frowned. She’s no bigger than a minute, with overdyed hair and an expression on her face like she’s just eaten a sour persimmon.

I waved at her, and she waved me to follow her to the back, where her office was.

In the back, she made Cathy sit at a table near the religious literature.

“What am I supposed to do?” Cathy asked.

Mother looked around the room at all the books. “You do know how to read, don’t you, dear?”

Cathy gave Mother a hard look. “Until my lips get tired.”

“Know anything about the Hindu religion?”

“Yeah. They don’t eat cows.”

“There, you’re already off to a good start.”

“Here,” Mother said, and gave her a booklet on the Hindu religion, then guided me into her office, which was only a little larger than a janitor’s closet, and closed the door. She sat behind her cluttered desk, and I sat in front of it.

“So, you must need money,” she said.

“When have I asked you for any?”

“Never, but since I haven’t seen you in a month of Sundays, and you live across town, I figured it had to be money. If it’s for that floozy out there, to buy her something—forget it. She looks cheap.”

“I don’t even know her that well,” I said.

She gave me a narrow-eyed look.

“No. It’s not like that. She’s a client.”

“I bet she is.”

“Listen, Mom, I’m going to jump right in. I have a situation. It has to do with the kind of things you know about.”

“That would be a long list.”

I nodded. “But this one is a very specialized thing.” And then I told her the story.

She sat silent for a while, processing the information.

“Cauldwell Hogson,” she said.

“Beg pardon?”

“The old graveyard, behind the fence. The one they don’t use anymore. He was buried there. Fact is, he was hanged in the graveyard from a tree limb. About where the old sawmill is now.”

“There are graves there?” I asked.

“Well, there were. The flood washed up a bunch of them. Hogson was one of the ones buried there, in an unmarked grave. Here—it’s in one of the books about the growth of the city, written in 1940.”

She got up and pulled a dusty-looking book off one of her shelves. The walls were lined with them. These were her personal collection. She put the book on her desk, sat back down, and started thumbing through the volume, then paused.

“Oh, what the heck. I know it by heart.” She closed the book, sat back down in her chair, and said, “Cauldwell Hogson was a grave robber. He stole bodies.”

“To sell to science?”

“No. To have . . . well, you know.”

“No. I don’t know.”

“He had relations with the bodies.”

“That’s nasty,” I said.

“I’ll say. He would take them and put them in his house and pose them and sketch them. Young women. Old women. Just as long as they were women.”

“Why?”

“Before daybreak, he would put them back. It was a kind of ritual. But he got caught and he got hung, right there in the graveyard. Preacher cursed him. Later they found his notebooks in his house, and his drawings of the dead women. Mostly nudes.”

“But Mom, I think I saw him. Or someone like him.”

“It could be him,” she said.

“You really think so?”

“I do. You used to laugh at my knowledge, thought I was a fool. What do you think now?”

“I think I’m confused. How could he come out of his grave after all these many years and start doing the things he did before? Could it be someone else? Someone imitating him?”

“Unlikely.”

“But he’s dead.”

“What we’re talking about here, it’s a different kind of dead. He’s a ghoul. Not in the normal use of the term—he’s a real ghoul. Back when he was caught, and that would be during the Great Depression, no one questioned that sort of thing. This town was settled by people from the old lands. They knew about ghouls. Ghouls are mentioned as far back as The Thousand and One Nights. And that’s just their first known mention. They love the dead. They gain power from the dead.”

“How can you gain power from something that’s dead?”

“Some experts believe we die in stages, and that when we are dead to this world, the brain is still functioning on a plane somewhere between life and death. There’s a gradual release of the soul.”

“How do you know all this?”

“Books. Try them sometime. The brain dies slowly, and a ghoul takes that slow dying, that gradual release of soul, and feasts on it.”

“He eats their flesh?”

“There are different kinds of ghouls. Some eat flesh. Some only attack men, and some are like Hogson. The corpses of women are his prey.”

“But how did he become a ghoul?”

“Anyone who has an unholy interest in the dead—no matter what religion, no matter if they have no religion—if they are killed violently, they may well become a ghoul. Hogson was certainly a prime candidate. He stole women’s bodies and sketched them, and he did other things. We’re talking about, you know—”

“Sex?”

“If you can call it that, with dead bodies. By this method he thought he could gain their souls and their youth. Being an old man, he wanted to live forever. Course, there were some spells involved, and some horrible stuff he had to drink, made from herbs and body parts. Sex with the bodies causes the remains of their souls to rise to the surface, and he absorbs them through his own body. That’s why he keeps coming back to a body until it’s drained. It all came out when he was caught replacing the body of Mary Lawrence in her grave. I went to school with her, so I remember all this very well. Anyway, when they caught him, he told them everything, and then there were his notebooks and sketches. He was quite proud of what he had done.”

“But why put the bodies back? And Susan, she looked like she was just sleeping. She looked fresh.”

“He returned the bodies before morning because for the black magic to work, they must lie at night in the resting place made for them by their loved ones. Once a ghoul begins to take the soul from a body, it will stay fresh until he’s finished, as long as he returns it to its grave before morning. When he drains the last of its soul, the body decays. What he gets out of all this, besides immortality, are powers he didn’t have as a man.”

“Like being strong and able to jump a six-foot fence flat footed,” I said.

“Things like that, yes.”

“But they hung the old man,” I said. “How in hell could he be around now?”

“They did more than hang him. They buried him in a deep grave filled with wet cement and allowed it to dry. That was a mistake. They should have completely destroyed the body. Still, that would have held him, except the flood opened the graves, and a bulldozer was sent in to push the old bones away. In the process, it must have broken open the cement and let him out.”

“What’s to be done?” I said.

“You have to stop it.”

“Me?”

“I’m too old. The cops won’t believe this. So it’s up to you. You don’t stop him, another woman dies, he’ll take her body. It could be me. He doesn’t care I’m old.”

“How would I stop him?”

“That part might prove to be difficult. First, you’ll need an ax, and you’ll need some fire . . .”

–

With Cathy riding with me, we went by the hardware store and bought an ax and a file to sharpen it up good. I got a can of paint thinner and a new lighter and a can of lighter fluid. I went home and got my twelve-gauge double barrel. I got a handful of shotgun shells. I explained to Cathy what I had to do.

“According to Mom, the ghoul doesn’t feel pain much. But they can be destroyed if you chop their head off, and then you got to burn the head. If you don’t, it either grows a new head, or a body out of the head, or some such thing. She was a little vague. All I know is she says it’s a way to kill mummys, ghouls, vampires, and assorted monsters.”

“My guess is she hasn’t tried any of this,” Cathy said.

“No, she hasn’t. But she’s well schooled in these matters. I always thought she was full of it, but turns out she isn’t. Who knew?”

“And if it doesn’t work?”

“Look for my remains.”

“I’m going with you,” she said.

“No you’re not.”

“Do you really think you can stop me? It’s my sister. I hired you.”

“Then let me do my job.”

“I just have your word for all this.”

“There you are. I wouldn’t tromp around in the dark based on my word.”

“I’m going.”

“It could get ugly.”

“Once again, it’s my sister. You don’t get to choose for me.”

–

I parked my car across the road from the cemetery under a willow. As it grew dark, shadows would hide it reasonably well. This was where Cathy was to sit. I, on the other hand, would go around to the rear, where the ghoul would most likely come en route to Susan’s grave.

Sitting in my jalopy talking, the sun starting to drop, I said, “I’ll try and stop him before he gets to the grave. But if he comes from some other angle, another route, hit the horn and I’ll come running.”

“There’s the problem of the six-foot fence,” Cathy said.

“I may have to run around the graveyard fence, but I’ll still come. You can keep honking the horn and turn on the lights and drive through the cemetery gate. But whatever you do, don’t get out of the car.”

I handed her my shotgun.

“Ever shot one of these?” I said.

“Daddy was a bird hunter. So, yes.”

“Good. Just in case it comes to it.”

“Will it kill him?”

“Mom says no, but it beats harsh language.”

I grabbed my canvas shoulder bag and ax and got out of the car and started walking. I made it around the fence and to the rear of the graveyard, near the creek and the mud, about fifteen minutes before dark.

I got behind a wide pine and waited. I didn’t know if I was in the right place, but if his grave had been near the sawmill this seemed like a likely spot. I got a piece of chewing gum and went to work on it.

The sun was setting.

I hoisted the ax in my hand, to test the weight. Heavy. I’d have to swing it pretty good to manage decapitation. I thought about that. Decapitation. What if it was just some nut, and not a ghoul?

Well, what the hell. He was still creepy.

I put the ax head on the ground and leaned on the ax handle.

I guess about an hour passed before I heard something crack. I looked out toward the creek where I had seen him jump with Susan’s body. I didn’t see anything but dark. I felt my skin prick, and I had a sick feeling in my stomach.

I heard another crack.

It wasn’t near the creek.

It wasn’t in front of me at all.

It was behind me.

–

I wheeled, and then I saw the ghoul. He hadn’t actually seen me, but he was moving behind me at a run, and boy could he run. He was heading straight for the cemetery fence.

I started after him, but I was too far behind and too slow. I slipped on the mud and fell. When I looked up, it was just in time to see the ghoul make a leap. For a moment, he seemed pinned against the moon, like a curious brooch on a golden breast. His long white hair trailed behind him and his coat was flying wide. He had easily leaped ten feet high.

He came down in the cemetery as light as a feather. By the time I was off my ass and had my feet under me, he was running across the cemetery toward Susan’s grave.

I ran around the edge of the fence, carrying the ax, the bag slung over my shoulder. As I ran, I saw him, moving fast. He was leaping gravestones again.

Before I reached the end of the fence, I heard my horn go off and saw lights come on. The car was moving. As I turned the corner of the fence, I could see the lights had pinned the ghoul for a moment, and the car was coming fast. The ghoul threw up its arm and the car hit him and knocked him back about twenty feet.

The ghoul got up as if nothing had happened. Its movements were puppetlike, as if it were being pulled by invisible strings.

Cathy, ignoring everything I told her, got out of the car. She had the shotgun.

The ghoul ignored her, and ran toward Susan’s grave, and started digging as if Cathy wasn’t there. As I came through the cemetery opening and passed my car, Cathy cut down on the thing with the shotgun. Both barrels.

It was a hell of a roar, and dust and cloth and flesh flew up from the thing. The blast knocked it down. It popped up like a jack-in-the-box and hissed like a cornered possum. It lunged at Cathy. She swung the shotgun by the barrel, hit the ghoul upside the head.

I was at Cathy’s side now, and without thinking I dropped the ax and the bag fell off my shoulder. Before the ghoul could reach her, I tackled the thing.

It was easy. There was nothing to Cauldwell Hogson. It was like grabbing a hollow reed. But the reed was surprisingly strong. Next thing I knew, I was thrown into the windshield of my car, and then Cathy was thrown on top of me.

When I had enough of my senses back, I tried to sit up. My back hurt. The back of my head ached, but otherwise, I seemed to be all in one piece.

The ghoul was digging furiously at the grave with its hands, throwing dirt like a dog searching for a bone. He was already deep into the earth.

Still stunned, I jumped off the car and grabbed the canvas bag, and pulled the lighter fluid and the lighter out of it. I got as close as I dared and sprayed a stream of lighter fluid at the creature. It soaked the back of its head. Hogson wheeled to look at me. I sprayed the stuff in his eyes and on his chest, drenching him. He swatted at the fluid as I squeezed the can.

I dropped the can. I had the lighter, and I was going to pop the top and hit the thumb wheel, when the next thing I knew the ghoul leaped at me and grabbed me and threw me at the cemetery fence. I hit hard against it and lay there stunned.

When I looked up, the ghoul was dragging the coffin from the grave, and without bothering to open it this time, threw it over his shoulder and took off running.

I scrambled to my feet, found the lighter, stuffed it in the canvas bag, swung the bag over my shoulder, and picked up the ax. I yelled for Cathy to get in the car. She was still dazed, but managed to get in.

Sliding behind the wheel, I gave her the ax and the bag, turned the key, popped the clutch, and backed out of the cemetery. I whipped onto the road, jerked the gear into position, and tore down the road.

“He’s over there!” Cathy said. “See!”

I glimpsed the ghoul running toward the creek with the coffin.

“I see,” I said. “And I think I know where he’s going.”

–

The sawmill road was good for a short distance, but then the trees grew in close and the road was grown up with small brush. I had to stop the car. We started rushing along on foot. Cathy carried the canvas bag. I carried the ax.

“What’s in the bag,” she said.

“More lighter fluid.”

Trees dipped their limbs around us, and when an owl hooted, then fluttered through the pines, I nearly crapped my pants.

Eventually, the road played out, and there were only trees. We pushed through some limbs, scratching ourselves in the process, and finally broke out into a partial clearing. The sawmill was in the center of it, with its sagging roof and missing wall and trees growing up through and alongside it. The moonlight fell over it and colored it like thin yellow paint.

“You’re sure he’s here,” Cathy said.

“I’m not sure of much of anything anymore,” I said. “But his grave was near here. It’s about the only thing he can call home now.”

When we reached the sawmill, we took deep breaths, as if on cue, and went inside. The boards creaked under our feet. I looked toward a flight of open stairs and saw the ghoul moving up those, as swift and silent as a rat. The coffin was on his shoulder, held there as if it were nothing more than a shoebox.

I darted toward the stairs, and the minute my foot hit them, they creaked and swayed.

“Stay back,” I said, and Cathy actually listened to me. At least for a moment.

I climbed on up, and then there was a crack, and my foot went through. I felt a pain like an elephant had stepped on my leg. I nearly dropped the ax.

“Taylor,” Cathy yelled. “Are you all right?”

“Good as it gets,” I said.

Pulling my leg out, I limped up the rest of the steps with the ax, turned left at the top of the stairs—the direction I had seen it take. I guess I was probably thirty feet high by then.

I walked along the wooden walkway. To my right were walls and doorways without doors, and to my left was a sharp drop to the rotten floor below. I hobbled along for a few feet, glanced through one of the doorways. The floor on the other side was gone. Beyond that door was a long drop.

I looked down at Cathy.

She pointed at the door on the far end.

“He went in there,” she said.

Girding my loins, I came to the doorway and looked in. The roof of the room was broken open, and the floor was filled with moonlight. On the floor was the coffin, and the slip Susan had worn was on the edge of the coffin, along with the ghoul’s rotten black coat.

Cauldwell Hogson was in the coffin on top of her.

I rushed toward him just as his naked ass rose up, a bony thing that made him look like some sad concentration-camp survivor. As his butt came down, I brought the ax downward with all my might.

It caught him on the back of the neck, but the results were not as I expected. The ax cut a dry notch, but up he leaped, as if levitating, grabbed my ax handle, and would have had me, had his pants not been around his ankles. It caused him to fall. I staggered back through the doorway, and now he was out of his pants and on his feet, revealing that though he was emaciated, one part of him was not.

Backpedaling, I stumbled onto the landing. He sprang forward, grabbed my throat. His hands were like a combination of vise and ice tongs; they bit into my flesh and took my air. Up close, his breath was rancid as roadkill. His teeth were black and jagged, and the flesh hung from the bones of his face like cheap curtains. The way he had me, I couldn’t swing the ax and not hit myself.

In the next moment, the momentum of his rush carried us backward, along the little walkway, and then out into empty space.

–

Falling didn’t take any time. When I hit the ground my air was knocked out of me, and the boards of the floor sagged.

The ghoul was straddling me, choking me.

And then I heard a click, a snap. I looked. Cathy had gotten the lighter from the bag. She tossed it.

The lighter hit the ghoul, and the fluid I had soaked him with flared. His head flamed, and he jumped off of me and headed straight for Cathy.

I got up as quickly as I could, which was sort of like asking a dead hippo to roll over. On my feet, lumbering forward, finding that I still held the ax in my hand, I saw that the thing’s head was flaming like a match, and yet it had gripped Cathy by the throat and was lifting her off the ground.

I swung the ax from behind, caught its left leg just above the knee. The blade I had sharpened so severely did its work. It cut the ghoul off at the knee, and he dropped, letting go of Cathy. She moved back quickly, holding her throat, gasping for air.

The burning thing lay on its side. I brought the ax down on its neck. It took me two more chops before its rotten, burning head came loose. I chopped at the head, sending the wreckage of flaming skull in all directions.

I faltered a few steps, looked at Cathy, said, “You know, when you lit him up, I was under him.”

“Sorry.”

And then I saw her eyes go wide.

I turned.

The headless, one-legged corpse was crawling toward us, swift as a lizard. It grabbed my ankle.

I slammed the ax down, took off the hand at the wrist, then kicked it loose of my leg. That put me in a chopping frenzy. I brought the ax down time after time, snapping that dry stick of a creature into thousands of pieces.

By the time I finished that, I could hardly stand. I had to lean on the ax. Cathy took my arm, said, “Taylor.”

Looking up, I saw the fire from the ghoul had spread out in front of us, and the rotten lumber and old sawdust had caught like paper. The canvas bag with the lighter fluid in it caught too, and within a second, it blew, causing us to fall back.

The only way out was up the stairs, and in the long run, that would only prolong the roasting. Considering the alternative, however, we were both for prolonging our fiery death instead of embracing it.

Cathy helped me up the stairs, because by now my ankle had swollen up until it was only slightly smaller than a Civil War cannon. I used the ax like a cane. The fire licked the steps behind us, climbed up after us, as if playing tag.

When we made the upper landing, we went through the door where Susan’s body lay. I looked in the coffin. She was nude, looking a lot rougher than before. Perhaps the ghoul had gotten the last of her, or without him to keep her percolating with his magic, she had gone for the last roundup, passed on over into true, solid death. I hoped in the end her soul had been hers, and not that monster’s.

I let go of Cathy, and, using the ax for support, made it to the window. The dark sawdust was piled deep below.

Stumbling back to the coffin, I dropped the ax, got hold of the edge, and said, “Push.”

My thinking was maybe we could save Susan’s body for reburial. Keep it away from flames. I didn’t need to explain to Cathy. She got it right away. Together we shoved the coffin toward the window.

We pushed the coffin and Susan out the window. She fell free of the box and hit the sawdust. We jumped after her.

When we were on the pile, spitting sawdust, trying to work our way down the side of it, the sawmill wall started to fall. We rolled down the side of the piled sawdust and hit the ground.

The burning wall hit the sawdust. The mound was high enough we were protected from it. We crawled out from under it and managed to get about fifty feet away before we looked back.

The sawmill, the sawdust, and poor Susan’s body—which we had not been able to save—and whatever was left of Cauldwell Hogson was now nothing more than a raging mountain of sizzling, crackling flames.

–

Joe R. Lansdale has been a freelance writer since 1973, and a full-time writer since 1981. He is the author of thirty novels and eighteen short-story collections, and has received the Edgar Award, seven Bram Stoker Awards, the British Fantasy Award, and Italy’s Grinzani Prize for Literature, among others.

“Bubba Ho-Tep,” his award-nominated novella, was filmed by Don Coscarelli and is now considered a cult classic, and his story “Incident On and Off a Mountain Road” was filmed for Showtime’s Masters of Horror.

He has written for film, television, and comics, and is the author of numerous essays and columns. His most recent works are a collection from the University of Texas Press, Sanctified and Chicken Fried; The Portable Lansdale; and Vanilla Ride, his latest in the Hap Collins–Leonard Pine series. The series has recently been released in paperback from Vintage Books.