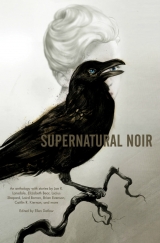

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

His most recent books are a short-fiction collection, Viator Plus, and a short novel, The Taborin Scale. Forthcoming are another short-fiction collection, Five Autobiographies; two novels, tentatively titled The Piercefields and The End of Life as We Know It (the latter, young adult); and a short novel, The House of Everything and Nothing.

| THE LAST TRIANGLE |

| THE LAST TRIANGLE |

Jeffrey Ford

–

I was on the street with nowhere to go, broke, with a habit. It was around Halloween, cold as a motherfucker in Fishmere—part suburb, part crumbling city that never happened. I was getting by, roaming the neighborhoods after dark, looking for unlocked cars to see what I could snatch. Sometimes I stole shit out of people’s yards and pawned it or sold it on the street. One night I didn’t have enough to cop, and I was in a bad way. There was nobody on the street to even beg from. It was freezing. Eventually I found this house on a corner and noticed an open garage out back. I got in there where it was warmer, lay down on the concrete, and went into withdrawal.

You can’t understand what that’s like unless you’ve done it. Remember that Twilight Zone where you make your own hell? Like that. I eventually passed out or fell asleep, and woke, shivering, to daylight, unable to get off the floor. Standing in the entrance to the garage was this little old woman with her arms folded, staring down through her bifocals at me. The second she saw I was awake, she turned and walked away. I felt like I’d frozen straight through to my spine during the night and couldn’t get up. A splitting headache, and the nausea was pretty intense too. My first thought was to take off, but too much of me just didn’t give a shit. The old woman reappeared, but now she was carrying a pistol in her left hand.

“What’s wrong with you?” she said.

I told her I was sick.

“I’ve seen you around town,” she said. “You’re an addict.” She didn’t seem freaked out by the situation, even though I was. I managed to get up on one elbow. I shrugged and said, “True.”

And then she left again, and a few minutes later came back, toting an electric space heater. She set it down next to me, stepped away and said, “You missed it last night, but there’s a cot in the back of the garage. Look,” she said, “I’m going to give you some money. Go buy clothes. You can stay here and I’ll feed you. If I know you’re using, though, I’ll call the police. I hope you realize that if you do anything I don’t like I’ll shoot you.” She said it like it was a foregone conclusion, and, yeah, I could actually picture her pulling the trigger.

What could I say? I took the money, and she went back into her house. My first reaction to the whole thing was to laugh. I could score. I struggled up all dizzy and bleary, smelling like the devil’s own shit, and stumbled away.

I didn’t cop that day, only a small bag of weed. Why? I’m not sure, but there was something about the way the old woman talked to me, her unafraid, straight-up approach. That, maybe, and I was so tired of the cycle of falling hard out of a drug dream onto the street and scrabbling like a three-legged dog for the next fix. By noon, I was pot high, downtown, still feeling shitty, when I passed this old clothing store. It was one of those places like you can’t fucking believe is still in operation. The mannequin in the window had on a tan leisure suit. Something about the way the sunlight hit that window display, though, made me remember the old woman’s voice, and I had this feeling like I was on an errand for my mother.

I got the clothes. I went back and lived in her garage. The jitters, the chills, the scratching my scalp and forearms were bad, but when I could finally get to sleep, that cot was as comfortable as a bed in a fairy tale. She brought food a couple times a day. She never said much to me, and the gun was always around. The big problem was going to the bathroom. When you get off the junk, your insides really open up. I knew if I went near the house, she’d shoot me. Let’s just say I marked the surrounding territory. About two weeks in, she wondered herself and asked me, “Where are you evacuating?”

At first I wasn’t sure what she was saying. “Evacuating?” Eventually, I caught on and told her, “Around.” She said that I could come in the house to use the downstairs bathroom. It was tough, ’cause every other second I wanted to just bop her on the head, take everything she had, and score like there was no tomorrow. I kept a tight lid on it till one day, when I was sure I was going to blow, a delivery truck pulled up to the side of the house and delivered, to the garage, a set of barbells and a bench. Later when she brought me out some food, she nodded to the weights and said, “Use them before you jump out of your skin. I insist.”

Ms. Berkley was her name. She never told me her first name, but I saw it on her mail, “Ifanel.” What kind of name is that? She had iron-gray hair, pulled back tight into a bun, and strong green eyes behind the big glasses. Baggy corduroy pants and a zip-up sweater was her wardrobe. There was a yellow one with flowers around the collar. She was a busy old woman. Quick and low to the ground.

Her house was beautiful inside. The floors were polished and covered with those Persian rugs. Wallpaper and stained-glass windows. But there was none of that goofy shit I remembered my grandmother going in for: suffering Christs, knitted hats on the toilet paper. Every room was in perfect order and there were books everywhere. Once she let me move in from the garage to the basement, I’d see her reading at night, sitting at her desk in what she called her “office.” All the lights were out except for this one brass lamp shining right over the book that lay on her desk. She moved her lips when she read. “Good night, Ms. Berkley,” I’d say to her and head for the basement door. From down the hall I’d hear her voice come like out of a dream, “Good night.” She told me she’d been a history teacher at a college. You could tell she was really smart. It didn’t exactly take a genius, but she saw straight through my bullshit.

One morning we were sitting at her kitchen table having coffee, and I asked her why she’d helped me out. I was feeling pretty good then. She said, “That’s what you’re supposed to do. Didn’t anyone ever teach you that?”

“Weren’t you afraid?”

“Of you?” she said. She took the pistol out of her bathrobe pocket and put it on the table between us. “There’s no bullets in it,” she told me. “I went with a fellow who died and he left that behind. I wouldn’t know how to load it.”

Normally I would have laughed, but her expression made me think she was trying to tell me something. “I’ll pay you back,” I said. “I’m gonna get a job this week and start paying you back.”

“No, I’ve got a way for you to pay me back,” she said and smiled for the first time. I was 99 percent sure she wasn’t going to tell me to fuck her, but, you know, it crossed my mind.

Instead, she asked me to take a walk with her downtown. By then it was winter, cold as a witch’s tit. Snow was coming. We must have been a sight on the street. Ms. Berkley, marching along in her puffy ski parka and wool hat, blue with gold stars and a tassel. I don’t think she was even five foot. I walked a couple of steps behind her. I’m six foot four inches, I hadn’t shaved or had a haircut in a long while, and I was wearing this brown suit jacket that she’d found in her closet. I couldn’t button it if you had a gun to my head and my arms stuck out the sleeves almost to the elbow. She told me, “It belonged to the dead man.”

Just past the library, we cut down an alley, crossed a vacant lot, snow still on the ground, and then hit a dirt road that led back to this abandoned factory. One story, white stucco, all the windows empty, glass on the ground, part of the roof caved in. She led me through a stand of trees around to the left side of the old building. From where we stood, I could see a lake through the woods. She pointed at the wall and said, “Do you see that symbol in red there?” I looked but all I saw was a couple of Fucks.

“I don’t see it,” I told her.

“Pay attention,” she said and took a step closer to the wall. Then I saw it. About the size of two fists. It was like a capital E tipped over on its three points, and sitting on its back, right in the middle, was an o. “Take a good look at it,” she told me. “I want you to remember it.”

I stared for a few seconds and told her, “Okay, I got it.”

“I walk to the lake almost every day,” she said. “This wasn’t here a couple of days ago.” She looked at me like that was supposed to mean something to me. I shrugged; she scowled. As we walked home, it started to snow.

Before I could even take off the dead man’s jacket, she called me into her office. She was sitting at her desk, still in her coat and hat, with a book open in front of her. I came over to the desk, and she pointed at the book. “What do you see there?” she asked. And there it was, the red, knocked-over E with the o on top.

I said, “Yeah, the thing from before. What is it?”

“The Last Triangle,” she said.

“Where’s the triangle come in?” I asked.

“The three points of the capital E stand for the three points of a triangle.”

“So what?”

“Don’t worry about it,” she said. “Here’s what I want you to do. Tomorrow, after breakfast, I want you to take a pad and a pen, and I want you to walk all around the town, everywhere you can think of, and look to see if that symbol appears on any other walls. If you find one, write down the address for it—street and number. Look for places that are abandoned, rundown, burned out.”

I didn’t want to believe she was crazy, but . . .

I said to her, “Don’t you have any real work for me to do—heavy lifting, digging, painting, you know?”

“Just do what I ask you to do.”

Ms. Berkley gave me a few bucks and sent me on my way. First things first, I went downtown, scored a couple of joints, bought a forty of Colt. Then I did the grand tour. It was fucking freezing, of course. The sky was brown, and the dead man’s jacket wasn’t cutting it. I found the first of the symbols on the wall of a closed-down bar. The place had a pink plastic sign that said Here It Is, with a silhouette of a woman with an Afro sitting in a martini glass. The E was there in red on the plywood of a boarded front window. I had to walk a block each way to figure out the address, but I got it. After that I kept looking. I walked myself sober and then some and didn’t get back to the house till nightfall.

When I told Ms. Berkley that I’d found one, she smiled and clapped her hands together. She asked for the address, and I delivered. She set me up with spaghetti and meatballs at the kitchen table. I was tired, but seriously, I felt like a prince. She went down the hall to her office. A few minutes later, she came back with a piece of paper in her hand. As I pushed the plate away, she set the paper down in front of me and then took a seat.

“That’s a map of town,” she said. I looked it over. There were two dots in red pen and a straight line connecting them. “You see the dots?” she asked.

“Yeah.”

“Those are two points of the Last Triangle.”

“Okay,” I said and thought, “Here we go . . .”

“The Last Triangle is an equilateral triangle; all the sides are equal,” she said.

I failed math every year in high school, so I just nodded.

“Since we know these two points, we know that the last point is in one of two places on the map, either east or west.” She reached across the table and slid the map toward her. With the red pen, she made two dots and then made two triangles sharing a line down the center. She pushed the map toward me again. “Tomorrow you have to look either here or here,” she said, pointing with the tip of the pen.

The next day I found the third one, to the east, just before it got dark. A tall old house, on the edge of an abandoned industrial park. It looked like there’d been a fire. There was an old rusted Chevy up on blocks in the driveway. The E-and-o thing was spray-painted on the trunk.

When I brought her that info, she gave me the lowdown on the triangle. “I read a lot of books about history,” she said, “and I have this ability to remember things I’ve seen or read. If I saw a phone number once, I’d remember it correctly. It’s not a photographic memory; it doesn’t work automatically or with everything. Maybe five years ago I read this book on ancient magic, The Spells of Abriel the Magus, and I remembered the symbol from that book when I saw it on the wall of the old factory last week. I came home, found the book, and reread the part about the Last Triangle. It’s also known as Abriel’s Escape or Abriel’s Prison.

“Abriel was a thirteenth-century magus . . . magician. He wandered around Europe and created six powerful spells. The triangle, once marked out, denotes a protective zone in which its creator cannot be harmed. There’s a limitation to the size it can be, each leg no more than a mile. At the same time that zone is a sanctuary, it’s a trap. The magus can’t leave its boundary, ever. To cross it is certain death. For this reason, the spell was used only once, by Abriel, in Dresden, to escape a number of people he’d harmed with his dark arts who had sent their own wizards to kill him. He lived out the rest of his life there, within the Last Triangle, and died at one hundred years of age.”

“That’s a doozy.”

“Pay attention,” she said. “For the Last Triangle to be activated, the creator of the triangle must take a life at its geographical center between the time of the three symbols being marked in the world and the next full moon. Legend has it, Abriel killed the baker Ellot Haber to induce the spell.”

It took me almost a minute and a half to grasp what she was saying. “You mean, someone’s gonna get iced?” I said.

“Maybe.”

“Come on, a kid just happened to make that symbol. Coincidence.”

“No, remember, a perfect equilateral triangle, each one of the symbols exactly where it should be.” She laughed, and, for a second, looked a lot younger.

“I don’t believe in magic,” I told her. “There’s no magic out there.”

“You don’t have to believe it,” she said. “But maybe someone out there does. Someone desperate for protection, willing to believe even in magic.”

“That’s pretty far fetched,” I said, “but if you think there’s a chance, call the cops. Just leave me out of it.”

“The cops,” she said and shook her head. “They’d lock me up with that story.”

“Glad we agree on that.”

“The center of the triangle on my map,” she said, “is the train-station parking lot. And in five nights there’ll be a full moon. No one’s gotten killed at the station yet, not that I’ve heard of.”

After breakfast she called a cab and went out, leaving me to fix the garbage disposal and wonder about the craziness. I tried to see it her way. She’d told me it was our civic duty to do something, but I wasn’t buying any of it. Later that afternoon, I saw her sitting at the computer in her office. Her glasses near the end of her nose, she was reading off the Internet and loading bullets into the magazine clip of the pistol. Eventually she looked up and saw me. “You can find just about anything on the Internet,” she said.

“What are you doing with that gun?”

“We’re going out tonight.”

“Not with that.”

She stopped loading. “Don’t tell me what to do,” she said.

After dinner, around dusk, we set out for the train station. Before we left, she handed me the gun. I made sure the safety was on and stuck it in the side pocket of the brown jacket. While she was out getting the bullets she’d bought two chairs that folded down and fit in small plastic tubes. I carried them. Ms. Berkley held a flashlight and in her ski parka had stashed a pint of blackberry brandy. The night was clear and cold, and a big waxing moon hung over town.

We turned off the main street into an alley next to the hardware store and followed it a long way before it came out on the south side of the train station. There was a rundown one-story building there in the corner of the parking lot. I ripped off the plywood planks that covered the door, and we went in. The place was empty but for some busted-up office furniture, and all the windows were shattered, letting the breeze in. We moved through the darkness, Ms. Berkley leading the way with the flashlight, to a back room with a view of the parking lot and station just beyond it. We set up the chairs and took our seats at the empty window. She killed the light.

“Tell me this is the strangest thing you’ve ever done,” I whispered to her.

She brought out the pint of brandy, unscrewed the top, and took a tug on it. “Life’s about doing what needs to get done,” she said. “The sooner you figure that out, the better for everyone.” She passed me the bottle.

After an hour and a half, my eyes had adjusted to the moonlight and I’d scanned every inch of that cracked, potholed parking lot. Two trains a half-hour apart rolled into the station’s elevated platform, and from what I could see, no one got on or off. Ms. Berkley was doing what needed to be done—namely, snoring. I took out a joint and lit up. I’d already polished off the brandy. I kept an eye on the old lady, ready to flick the joint out the window if I saw her eyelids flutter. The shivering breeze did a good job of clearing out the smoke.

At around three a.m., I’d just about nodded off, when the sound of a train pulling into the station brought me back. I sat up and leaned toward the window. It took me a second to clear my eyes and focus. When I did, I saw the silhouette of a person descending the stairs of the raised platform. The figure passed beneath the light at the front of the station, and I could see it was a young woman, carrying a briefcase. I wasn’t quite sure what the fuck I was supposed to be doing, so I tapped Ms. Berkley. She came awake with a splutter and looked a little sheepish for having corked off. I said, “There’s a woman heading to her car. Should I shoot her?”

“Very funny,” she said and got up to stand closer to the window.

I’d figured out which of the few cars in the parking lot belonged to the young woman. She looked like the white-Honda type. Sure enough, she made a beeline for it.

“There’s someone else,” said Ms. Berkley. “Coming out from under the trestle.”

“Where?”

“Left,” she said, and I saw him, a guy with a long coat and hat. He was moving fast, heading for the young woman. Ms. Berkley grabbed my arm and squeezed it. “Go,” she said. I lunged up out of the chair, took two steps, and got dizzy from having sat for so long. I fumbled in my pocket for the pistol as I groped my way out of the building. Once I hit the air, I was fine, and I took off running for the parking lot. Even as jumped up as I was, I thought, “I’m not gonna shoot anyone,” and left the gun’s safety on.

The young woman saw me coming before she noticed the guy behind her. I scared her, and she ran the last few yards to her car. I watched her messing around with her keys and didn’t notice the other guy was also on a flat-out run. As I passed the white Honda, the stranger met me and cracked me in the jaw like a pro. I went down hard but held onto the gun. As soon as I came to, I sat up. The guy—I couldn’t get a good look at his face—drew a blade from his left sleeve. By then the woman was in the car, though, and it screeched off across the parking lot.

He turned, brandishing the long knife, and started for me.

You better believe the safety came off then. That instant, I heard Ms. Berkley’s voice behind me. “What’s the meaning of this?” she said in a stern voice. The stranger looked up, and then turned and ran off, back into the shadows beneath the trestle.

“We’ve got to get out of here,” she said and helped me to my feet. “If that girl’s got any brains, she’ll call the cops.” Ms. Berkley could run pretty fast. We made it back to the building, got the chairs, the empty bottle, and as many cigarette butts as I could find, and split for home. We stayed off the main street and wound our way back through the residential blocks. We didn’t see a soul.

I couldn’t feel how cold I was till I got back in the house. Ms. Berkley made tea. Her hands shook a little. We sat at the kitchen table in silence for a long time.

Finally, I said, “Well, you were right.”

“The gun was a mistake, but if you didn’t have it, you’d be dead now,” she said.

“Not to muddy the waters here, but that’s closer to dead than I want to get. We’re gonna have to go to the police, but if we do, that’ll be it for me.”

“You tried to save her,” said Ms. Berkley. “Very valiant, by the way.”

I laughed. “Tell that to the judge when he’s looking over my record.”

She didn’t say anything else, but left and went to her office. I fell asleep on the cot in the basement with my clothes on. It was warm down there by the furnace. I had terrible dreams of the young woman getting her throat cut but was too tired to wake from them. Eventually, I came to with a hand on my shoulder and Ms. Berkley saying, “Thomas.” I sat up quickly, sure I’d forgotten to do something. She said, “Relax,” and rested her hand for a second on my chest. She sat on the edge of the cot with her hat and coat on.

“Did you sleep?” I asked.

“I went back to the parking lot after the sun came up. There were no police around. Under the trestle, where the man with the knife had come from, I found these.” She took a handful of cigarette butts out of her coat pocket and held them up.

“Anybody could have left them there at any time,” I said. “You read too many books.”

“Maybe, maybe not,” she said.

“He must have stood there waiting for quite a while, judging from how many butts you’ve got there.”

She nodded. “This is a serious man,” she said. “Say he’s not just a lunatic, but an actual magician?”

“Magician,” I said and snorted. “More like a creep who believes his own bullshit.”

“Watch the language,” she said.

“Do we go back to the parking lot tonight?” I asked.

“No, there’ll be police there tonight. I’m sure that girl reported the incident. I have something for you to do. These cigarettes are a Spanish brand, Ducados. I used to know someone who smoked them. The only store in town that sells them is over by the park. Do you know Maya’s Newsstand?”

I nodded.

“I think he buys his cigarettes there.”

“You want me to scope it? How am I supposed to know whether it’s him or not? I never got a good look at him.”

“Maybe by the imprint of your face on his knuckles?” she said.

I couldn’t believe she was breaking my balls, but when she laughed, I had to.

“Take my little camera with you,” she said.

“Why?

“I want to see what you see,” she said. She got up then and left the basement. I got dressed. While I ate, she showed me how to use the camera. It was a little electronic job, but amazing, with telephoto capability and a little window you could see your pictures in. I don’t think I’d held a camera in ten years.

I sat on a bench in the park, next to a giant pine tree, and watched the newsstand across the street. I had my forty in a brown paper bag and a five-dollar joint in my jacket. The day was clear and cold, and people came and went on the street, some of them stopping to buy a paper or cigs from Maya. One thing I noticed was that nobody came to the park, the one nice place in crumbling Fishmere.

All afternoon and nothing criminal, except for one girl’s miniskirt. She was my first photo—exhibit A. After that I took a break and went back into the park, where there was a gazebo looking out across a small lake. I fired up the joint and took another pic of some geese. Mostly I watched the sun on the water and wondered what I’d do once the Last Triangle hoodoo played itself out. Part of me wanted to stay with Ms. Berkley, and the other part knew it wouldn’t be right. I’d been on the scag for fifteen years, and now somebody’s making breakfast and dinner every day. Things like the camera, a revelation to me. She even had me reading a book, The Professor’s House by Willa Cather—slow as shit, but somehow I needed to know what happened next to old Godfrey St. Peter. The food, the weights, and staying off the hard stuff made me strong.

Late in the afternoon, he came to the newsstand. I’d been in such a daze, the sight of him there, like he just materialized, made me jump. My hands shook a little as I telephotoed in on him. He paid for two packs of cigs, and I snapped the picture. I wasn’t sure if I’d caught his mug. He was pretty well hidden by the long coat’s collar and the hat. There was no time to check the shot. As he moved away down the sidewalk, I stowed the camera in my pocket and followed him, hanging back fifty yards or so.

He didn’t seem suspicious. Never looked around or stopped, but just kept moving at the same brisk pace. Only when it came to me that he was walking us in a circle did I get that he was on to me. At that point, he made a quick left into an alley. I followed. The alley was a short one with a brick wall at the end. He’d vanished. I walked cautiously into the shadows and looked around behind the dumpsters. There was nothing there. A gust of wind lifted the old newspapers and litter into the air, and I’ll admit I was scared. On the way back to the house, I looked over my shoulder about a hundred times.

I handed Ms. Berkley the camera in her office. She took a wire out of her desk drawer and plugged one end into the camera and one into the computer. She typed some shit, and then the first picture appeared. It was the legs.

“Finding the focus with that shot?” she asked.

“Everyone’s a suspect,” I said.

“Foolishness,” she murmured. She liked the geese, said it was a nice composition. Then the one of the guy at the newsstand came up, and, yeah, I nailed it. A really clear profile of his face. Eyes like a hawk and a sharp nose. He had white hair and a thick white mustache.

“Not bad,” I said, but Ms. Berkley didn’t respond. She was staring hard at the picture and her mouth was slightly open. She reached out and touched the screen.

“You know him?” I asked.

“You’re wearing his jacket,” she said. Then she turned away, put her face in her hands.

I left her alone and went into the kitchen. I made spaghetti the way she’d showed me. While stirring the sauce, I said to my reflection in the stove hood, “Now the dead man’s back, and he’s the evil magician?” Man, I really wanted to laugh the whole thing off, but I couldn’t forget the guy’s disappearing act.

I put two plates of spaghetti down on the kitchen table and then went to fetch Ms. Berkley. She told me to go away. Instead I put my hands on her shoulders and said, “Come on, you should eat something.” Then, applying as little pressure as possible, I sort of lifted her as she stood. In the kitchen, I held her chair for her and gave her a cup of tea. My spaghetti was undercooked and the sauce was cold, but still, not bad. She used her napkin to dry her eyes.

“The dead man looks pretty good for a dead man,” I said.

“It was easier to explain by telling you he was dead. Who wants the embarrassment of saying someone left them?”

“I get it,” I said.

“I think most people would, but still . . .”

“This clears something up for me,” I told her. “I always thought it was pretty strange that two people in the same town would know about Abriel and the Last Triangle. I mean, what’s the chances?”

“The book is his,” she said. “Years after he left, it just became part of my library, and eventually I read it. Now that I think of it, he read a lot of books about the occult.”

“Who is he?”

“His name is Lionel Brund. I met him years ago, when I was in my thirties. I was already teaching at the college, and I owned this house. We both were at a party hosted by a colleague. He was just passing through and knew someone who knew someone at the party. We hit it off. He had great stories about his travels. He liked to laugh. It was fun just going to the grocery store with him. My first real romance. A very gentle man.”

The look on her face made me say, “But?”

She nodded. “But he owned a gun, and I had no idea what kind of work he did, although he always had plenty of money. Parts of his life were a secret. He’d go away for a week or two at a time on some ‘business’ trip. I didn’t mind that, because there were parts of my life I wanted to keep to myself as well. We were together, living in this house, for over two years, and then, one day, he was gone. I waited for him to come back for a long time and then moved on, made my own life.”

“Now you do what needs to get done,” I said.

She laughed. “Exactly.”

“Lionel knows we’re onto him. He played me this afternoon, took me in a circle and then was gone with the wind. It creeped me.”

“I want to see him,” she said. “I want to talk to him.”

“He’s out to kill somebody to protect himself,” I said.

“I don’t care,” she said.

“Forget it,” I told her and then asked for the gun. She pushed it across the table to me.

“He could come after us,” I said. “You’ve got to be careful.” She got up to go into her office, and I drew the butcher knife out of its wooden holder on the counter and handed it to her. I wanted her to get how serious things were. She took it but said nothing. I could tell she was lost in the past.

I put the gun, safety off, on the stand next to my cot and lay back with a head full of questions. I stayed awake for a long while before I eventually gave in. A little bit after I dozed off, I was half wakened by the sound of the phone ringing upstairs. I heard Ms. Berkley walk down the hall and pick up. Her voice was a distant mumble. Then I fell asleep for a few minutes, and the first thing I heard when I came to again was the sound of the back door closing. It took me a minute to put together that he’d called and she’d gone to meet him.

I got dressed in a flash, but put on three T-shirts instead of wearing Lionel’s jacket. I thought he might have the power to spook it since it belonged to him. It took me a couple of seconds to decide whether to leave the gun behind as well. But I was shit scared so I shoved it in the waist of my jeans and took off. I ran dead out to the train-station parking lot. Luckily there were no cops there, but there wasn’t anybody else either. I went in the station, searched beneath the trestles, and went back to the rundown building we’d sat in. Nothing.