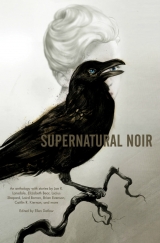

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

January imagines the theme is carried all the way around. Around the curve of the building, the milk-glass snows probably melt out in lime green and gold.

The band organ almost blows her hair back as she passes inside. It thumps through the cold cement floor. The bass drum shudders in the empty spaces of her chest. The lofty space isn’t as warm as she’d hoped—cold air settles along the neckline of the pushed-back hood of her cardigan—but it’s bright and crowded and full of the smell of popcorn and the voices of crowds of people January knows sort of halfway well, or used to know well in college.

She waves with her free hand as she moves around the outskirts of the carousel, looking for the birthday boy, the snack table, or both. The crowd keeps her from getting a good look at the merry-go-round; apparently Martin can turn out enough friends for his fiftieth to make even a carousel housing seem crowded. But that’s okay; she can wait until she’s found Martin to go pet the wooden ponies.

As if her determination were a summoning, he materializes before her, one hand extended for the plate and the other to take her shoulder and kiss her quickly in hello. He’s got crow’s feet and spectacles now, and he’s thicker in the middle than when they were lovers. The hair slicked back into his ponytail is more silver than ginger.

He points to the brownies with the corner of his eyeglasses. “Adulterated table?”

“Would I let you down?”

He grins, a grin that pays for all their long and questionable history, and takes her arm. Progress to the refreshments is slow—the penalty for traveling with the guest of honor—but the inevitable interruptions allow January to gaze her fill upon the carousel.

Because she was curious, and because she has the research skills of any good children’s librarian, she knows that it was carved between 1911 and 1914 by Russian Jews who had immigrated to Ohio. She knows that their previous work was carving ladies’ hair ornaments, and she knows that the carousel stood in its original setting for fifty years before being shipped east to its new place of pride as the focal point of a municipal park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted—where you can rent it for birthday parties at night or in the off-season.

But that’s not the kind of knowledge that can prepare one for the glow of lights and the flash of mirrors, the chiaroscuro and the colors. The crashing of the Wurlitzer echoes until January can only make out what Martin is saying because she knows him so well, and eventually they find themselves by the snack tables.

The larger one has a white cloth, and is covered with casseroles and chips and desserts. A cooler must contain cans of soda. The smaller one has a tie-dyed cloth, and the cooler underneath contains beer.

Martin sets her plate in the center of the display, whisking off the plastic to reveal a stack of two-bite chocolate squares, each stuck with a toothpick with a paper cannabis leaf glued to the top—just in case there should be any misunderstandings. Before he turns away, he liberates a brownie. “You made these kind of small.”

“I made them kind of strong,” she answers. A responsible herbalist always tests the merchandise before turning it loose. “Anyway, there’s three-quarters of a pound of chocolate in those things.”

Judging by the blissful expression that crosses his face when he sniffs the brownie, that’s the right ratio. “Someday, these will be nearly legal again.”

“Nah,” January says. She takes Martin’s arm and leads him toward the carousel. “It’ll take generations to recover from the eighties. Come on. Let’s ride.”

Despite the crush of people, there’s no real line, and even if there were, clinging to the birthday boy’s arm has its benefits. Martin, licking brownie grease off his opposite thumb, hands January up onto the deck of the carousel, which—unlike the smaller merry-go-rounds she rode as a kid—doesn’t settle beneath her weight.

Martin releases her hand. The Wurlitzer hesitates.

The carousel has more than just horses. The closest animals, three abreast, are giraffes, vivid yellow and chocolate brown with caparisons of gold and red and blue. Their long necks look knotty; January can see the places where one piece of wood was joined to another to make up the length. The giraffes look awkward and their blown-glass eyes bulge unnaturally, catching the harsh glow and reflecting it back like raccoon eyes in headlights.

“Lasers fully charged.”

“I don’t think the carvers ever saw a live giraffe.” Martin’s a contractor now—four years of college and it turns out he’s that much happier with a hammer in his hands. It took him years of thrashing to figure it out, but the fun of being fifty is having done the figuring.

He ducks to inspect the hooves. “These don’t move. Do giraffes really have hooves? I’d have thought camel feet.”

“They really do.” She reaches way up to pat the nearest giraffe on the nose. “And the next row go up and down. It looks like just the circus animals don’t move.”

Martin stands as if the rising thunder of the Wurlitzer raised him. He leans around the giraffe to follow her gaze. The next row of three is horses, and if the giraffes are stiff, the horses are stunning. The Russian cousins were apparently better at familiar animals, because these breathe. They’re slightly caricatured, flaring nostrils and bulging eyes—glass again, too-round bubbles affixed to the insides of the hollow heads, so the carousel lights shine through them—but the cartoonishness expresses itself as heroism rather than ridiculousness. The carved necks arch, the carved teeth champ, the carved manes mount like breaking waves. The outside horse in each row is larger and braver than his brothers, the exterior side of each pony more brilliantly decorated than the one inside.

January touches a palomino ear and feels a thrill. She walks the length of the horse, letting her fingers trail down his neck and across the saddle. The saddlecloth sparkles with silver gilt, though the stirrup irons hanging from stretched leathers are worn. When her fingers reach the tail, she almost jerks back; there’s hide under the cream-colored locks. It’s a real horsetail.

“Better pick a pony,” Martin says. “The ride is filling up.”

She smiles and moves on. Past a lovers’ carriage—red and gold, and decorated with cherubs even more uncanny than the giraffes—and another row of standees—elephant, lion, and tiger. (“How come the giraffes get three representatives?” Martin wants to know, and under her breath January answers, “Quotas.”) The elephant is a little questionable, and the lion and tiger are not to scale—the lion is largest of the three—but the carving on the big cats is spectacular. Their eyes squint over frozen snarls. Pink tongues roll slickly behind curved yellow fangs. Small chips at the tops of each canine tooth must be from children shoving their hands into the big cats’ mouths. She shudders. Even in play, who would want to do that?

Behind them are grays—and January’s heart skips. The inside pony might be the plainest on the carousel—in fact, January wonders if she was borrowed from an older merry-go-round to make up a gap—and the stallion on the outside is a heavy-hoofed, broad-shouldered draught horse, his whiskery head so huge it looks like his neck is bowed under the weight of it. But the mare in the middle is perfect—medium sized, caught at the bottom of her leap for easy mounting, and with a gentle expression and crimson leaves braided into the toss of her mane.

“Her,” January says, and strokes the pale-pink wooden muzzle under the long, dappled wooden nose.

“Oh, not the middle one,” says Martin. “You can’t catch the brass ring if you’re on the middle one.”

“Brass ring?” January tucks her long, felted-wool skirt around her tights.

“Sure,” Martin says. “This carousel still has brass rings. Catch one, and you get a free ride.”

“But the rides are all free—”

He waves his hand in that airy manner that used to make her want to kiss him, dismissing all protests. “It’s the principle.”

She rolls her eyes and puts on her best I’m humoring Martin face. Recognizing it, he grins.

“Fine, but I’m riding Buttercup next time.”

“Buttercup? You’re not keeping her—”

He stands aside so she can mount the stallion, but it still looks uncomfortably wide, and she turns to the plain little filly on the inside. She’s stiffer than the others, more plainly made, her seams more apparent. Even her paint looks dull. The bulging glass eyes are more crudely fitted, and this pony has not only a tail of real horsehair, but a mane also, mingled strands of black and white and gray.

“Macabre,” January says, petting it, and swings up into the saddle.

It’s been a long time since she was on a real horse, and she’s never done it in heels—even low heels like these Mary Jane clogs. But once her feet are in the stirrups and she’s remembering how to use the leverage, she finds herself sitting comfortably, legs extended, one hand resting on the spiraling brass sleeve that covers the steel pole the horse hangs from. Her skirt drapes the saddle like a lady’s cloak in a tapestry.

“Brass ring,” she says to Martin, who is watching her from under furrowed brow.

“Brass ring.” He swings onto the stallion, which—at the top of its arc—makes him seem miles and miles taller.

Other riders fill in. The elephant immediately in front of January is occupied by Martin’s freshman-year roommate Andrew. His narrow height is distorted in the middle by a potbelly now, but his colorless hair still sticks out every which way, though there is less of it. He dangles himself over the back of the beast and extends one telescopic arm to pat the dragonfly ornament between the gray filly’s eyes. “You got the ugliest ride in the joint again.”

“But the elephant has the ugliest rider,” she answers, and watches him try to take it as a joke, the way people who camouflage their viciousness as humor generally have to. He manages, more or less, but while he’s arranging his face January rolls her eyes at Martin.

Martin rolls them right back. Andrew must catch the exchange, because he says, “Don’t tell me you two are back together?” in a prickly voice, which makes Martin laugh like he’ll never stop.

January grins at him, and the carousel starts.

–

Ripples of force spread across the girl’s flesh from the clean entry wound, small as a puncture. The impact and transfer of force cause cavitation: shock waves blow the path of the bullet as wide as if a fist were shoved into the injury. The wound collapses again.

Human skin and muscle are elastic; bone and liver are not.

–

January is getting the hang of this brass-ring thing. She’d expected they would be on hooks overhead, so you’d have to stand in the saddle to reach. In retrospect, that strikes her as a silly supposition—imagine the liability issues!—but how was she supposed to know? She’s never seen a carousel that still has them before.

The rings are in long-armed dispensers, one outside and one inside the deck of the carousel, between the inner edge and the brightly painted and bemirrored drum. They are easy to reach—January doesn’t have to lean far out of her saddle to hook her fingers through one—but they are mostly not shiny brass at all. All the ones she collects are sweat tarnished and dull brown, but there’s still something satisfying about the hook, the tug, the click, the release.

Andrew, with his long arms and quick fingers, is getting two or three rings at once. He can reach out ahead, swipe the first, and the dispenser has reloaded before he’s out of range. Martin is much more casual about it. He snags his rings as if lifting an hors d’oeuvre from a passing waiter’s tray. Martin is mugging for her, feet out of the stirrups, knees drawn up, sitting high in the saddle of the big carved Percheron as if he were a jockey in the Kentucky Derby. She wants to tell him not to fall and split his head open, but she’s also known him long enough to know better.

There are probably worse ways to die.

The painted ponies don’t just go up and down (sorry, Joni Mitchell)—they travel in geared circles, undulating forward as the carousel spins. The Wurlitzer booms and squeaks and plinks. Inside it, January imagines bellows and hammers and little plinky valves. The bars on the glockenspiel jump when struck, and the swell shutters on its gold-and-white face open and shut, controlling the volume.

“Dixie” is ending and January expects the carousel to slow, but apparently it’s two songs a ride, because the Wurlitzer hiccups and wheezes and swings into “Bicycle Built for Two” as she comes around again. Andrew snags a brown ring, two, and as he palms the second one January sees a gold-bright flash of brass when his hand comes down.

She’s not prepared for the jump of her heart, the surge of adrenaline, the way it feels, for a moment, as if the pony under her stretches warm, real flanks and surges forward. She leans into the stirrup, skirt furling in the wind of her passage, feeling the tension and strength up her leg, and lets her fingers grope forward—

But Andrew’s fingers flash again, there’s the rattle of the springs, and the brass ring is gone, replaced by one dull and lifeless. January settles into the stirrups, balanced again, the strain equalized through both legs. Whatever trick of perception made the gray filly seem to move like a real horse is gone, and she’s just a painted pony again.

After the ride, Andrew tries to give January the brass ring, but she decides she’d rather have a brownie.

–

Before the bullet strikes the girl, it is blown from the muzzle of the pistol at a velocity of some 830 feet per second, pushed before a cloud of hot, expanding gases. Those gases, the product of combustion, are created when the propellant in the bullet’s cartridge undergoes deflagration. Smokeless powder is a solid propellant, and it burns rather than detonating.

Rifling along the barrel of the pistol (a brand-new, innovative Colt 1911 model, all blued steel and the gin smell of gun oil) imparted a spin to the bullet, gyroscopically stabilizing its trajectory and improving its accuracy. In this instance, the rifling made no difference to the outcome. A bullet doesn’t wobble much at point-blank range.

–

January dangles a paper cup of hot cider by the rolled edges to avoid burning her fingers and listens to Martin talk to Jeff about mortgages and gardening. It’s a better conversation than you’d expect—Jeff is younger, in his thirties, a muscular African American with mobile, elegant hands. He’s a work friend of Martin’s from before Martin owned his own company, and he’s sharply witty and not too impressed with what one of January’s lesbian friends calls the Social Program.

In any case, Jeff is in the midst of an involved history of his attempts to use nonlethal force to keep what he refers to as the Yard Bunny from consuming his corn plants when the brownie takes hold of Martin. Because Martin blinks, holds up a hand to pause Jeff’s conversation, and says, in his best Tommy Chong, “Whooaaaa.”

Jeff switches gears effortlessly—“Colors?”—leaving January making a mental note to get the rest of the bunny story later. Somehow, she suspects that the beleaguered corn plants were not the final victors.

“Good brownies,” Martin says, with a grin. “Don’t eat two. For a minute there, I thought the ponies were moving.”

“It’s a carousel,” Jeff says. “They’re supposed to.”

Martin flips him off genially. “A lot of help you are.”

January feels the uncontrollable swell of her Internet research toward her vocal cords, and doesn’t even try to choke it down. “You know this carousel is supposed to be haunted?”

Jeff cocks his head; Martin stops with his glass already tilted toward his mouth. “Haunted? No kidding. What do they say?”

“Well . . .” She leans forward conspiratorially, to draw the anticipation out a little. “Supposedly it runs backward at night, and Martin, you’re not the first one to think he’s seen the horses moving. And there are the usual reports of cold spots, weird film exposures, shadows with nothing to cast them—”

“Runs backward?” Martin checks ostentatiously over each shoulder. “Hey, has anyone seen that nice Mr. Cooger?”

January tosses her head back and laughs. It feels good, easy, and that’s not just the influence of the brownie. “I dunno,” she says, “but some kid was looking for you. Do you think ghosts affect digital cameras?”

Jeff opens his hands, expressing something that could be bewilderment unless he’s simply making the universal gesture for the ineffable. “Yeah,” he says. “Supposedly you get the same kind of effects. Cameras pick up all sorts of things the human eye doesn’t.”

“Ghosts are kind of Jeff’s hobby,” Martin says.

“Nah, nah, now.” Jeff stretches out one hand with a finger extended, drawing it through the space between him and Martin. “Call it an interest. It’s kind of inevitable, given my work.”

Jeff specializes in renovating old houses. In this part of the world, old means eighteenth century, or the early part of the nineteenth. Not at all an old house by England’s standards, but then, in England they don’t generally build dwelling places out of wood.

January can’t resist. ’Tis the season, after all—Martin’s birthday is only a week before Halloween. “Have you ever seen a ghost?”

Jeff grins, flash of teeth stained slightly from too much coffee, and January suddenly finds him beautiful. Martin nudges her. He sees through her like a sheet of oiled paper. Try not to perv on the infants, you dirty old woman.

Jeff, thank God, seems oblivious. He’s busy gathering himself for whatever tall tale he’s about to tell, his attention somewhere off to the right while he figures out where to start. Just when January is starting to get antsy, he folds his fingers together and begins. “So you know contractors leave gifts inside houses, right?”

January doesn’t. “Gifts?”

Jeff’s head bobs emphatically, while Martin folds one arm over the other and lets his shoulders drop, his own cup of apple cider still hanging from his left hand. Either his cooled off faster than January’s, or his hands are impervious. “I like to leave a nice bottle of Scotch and a newspaper. Some guys do wine, photos, toys—it’s just kind of a message to the next guy to knock the wall down from the last one.”

“A gift,” January says, understanding. “Like when you sell a house, you leave toilet paper and paper towels for the people moving in.”

Jeff laughs, delighted. “Maybe not quite that practical. Anyway, I’ve found the damnedest things inside houses. Like, once a pair of suede slippers, new in box, except not such a great idea, because some kind of bugs had eaten them. Wine is common. Sometimes it’s vinegar. Scotch is a better idea.” He nods to Martin. “I like to leave books. Classics, nice editions. But you have to seal them up really well or they wind up like the slippers.”

“So what does this have to do with ghosts?” January rolls cider over her tongue. The taste is fruity, acid, complicated even before you consider the layers of sweet spices. She thinks there’s orange peel in there, star anise, allspice, cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, clove. And some unexpected things—black pepper, maybe. Bay leaf. It makes her want to suck air over it and rub her tongue against her palate to extract the subtleties.

“Well, so this one house had a china plate in the wall,” he says. “Willowware, sealed in a tiny little crate with wood shavings for packing material. Anyway, funny thing—as soon as I took that plate out, everything with the job started to go wrong.”

“It’s supposed to be a creepy doll,” Martin says, “that comes to life and starts trying to kill people until the final girl scorches its face off with a steam iron.”

Colored swirls follow the men’s movements. January knows they’re not real, but they are pretty.

“Now, when I say everything, I mean—drill bits snapping, nail guns jamming, the homeowner complaining of cold spots and feeling watched all the time. She was expecting a baby—we were renovating the nursery—and she eventually miscarried. So the husband took the plate and boxed it up, with styrofoam this time, instead of the wood shavings. And I opened the wall back up and tucked it inside, nice and careful.” He pauses, heavily, and raises one hand as if avowing, attesting, and swearing. “And that was the end of the troubles.”

Martin says, “It doesn’t sound as if anybody saw a ghost.”

“Cold spots.” January shivers dramatically. “Very good sign of a ghost infestation. If you have cold spots, look for ghosts.”

“If you have sawdust, look for termites.” Martin unfolds his arms and touches her. “Come on, I’m starving. You think there’s some food still left that isn’t laced?”

“Stoners,” Jeff says, following them back to the snack bar. “So predictable.”

–

Jeff and Martin start talking about repairing antique wood paneling in technical detail, and January decides that this is the opportune time to visit the snack tables. She pushes through the press of people and gets herself a small popcorn, more for the smell than the taste, and checks on the status of her brownies. Despite being cut small, they have already attrited by half. A small, round, white woman in a flowing skirt stops her, blue eyes peering through slipping strands of straight gray-brown hair that hang to her nominal waist. “You’re January, right?”

January nods, groping after a half-remembered name. “Mmm—Martha?”

“Marsha,” the woman says, with a winning smile and a negligent wave of her hand. “Don’t sweat it. I just wanted to say the brownies are really good. How do you get them not to be gritty?”

“Family secret,” January says. “It’s all about the butter. Pardon me.” She winks and turns away, as unenthralled suddenly with the technical details of infusing herb extracts into fats as she was with dadoing mahogany for tongue-and-groove construction. The line for the carousel has thinned as the evening has progressed, and since a group has just gone in, there is nobody standing at the gate. January presents herself just as the young Latina in gray coveralls who apparently came with the rental is closing the latch.

The carousel operator smiles apologetically. “I’m sorry,” she says. “Next ride?”

“I’m in no hurry,” January answers.

The woman nods and turns away to start the great machine revolving. She must have filled both hoppers with rings already, because as the music swells and the mounts begin to revolve she swings neatly up a stepladder and grabs a lever that extends both arms. The sound of wood on wood is almost buried under the Wurlitzer’s noise.

She comes back, dusting her hands, with a grin that makes January want to befriend her.

“Do you like your job?”

The woman looks down shyly. “I don’t mind it. Sometimes the kids’ birthday parties are a bit hairy, and sometimes it’s drunk college kids. We had a wedding in September. That was nice.”

“I work in a library.” January tosses her hair behind her shoulder. “I hear you about the kids.”

She extends her barely touched popcorn to the woman, who waves it off.

“Once you’ve worked here a month, you can’t get near the stuff anymore.” She wipes her hand on her trousers before she sticks it out and waits for January to clasp it. “I’m Maricela.”

“January,” January replies, giving her a little squeeze.

Maricela’s face softens with surprise—possibly even shock. “You’re pulling my leg.”

January is used to reactions, but this one seems a little over the top. “Fifty-one years,” she says. “Is there some reason it shouldn’t be?”

“No,” Maricela says, visibly gathering herself. “It’s just a little unusual, is all. A weird coincidence. Do you like carousels?”

“Love ’em,” January says. It isn’t as if she could have missed Maricela changing the subject. “More now than before. I read up on them when I found out Martin was throwing himself a kid party.”

“Everybody needs a kid party now and again,” Maricela says. “Especially people who don’t have kids. So you know about the horses having a romance side, the outside that’s all carved and pretty?”

“And a back side,” January says. “Which is so plain it doesn’t even get a pretty name.”

Maricela laughs, nodding.

Behind January, someone whoops, having caught the brass ring. It sounds like a child, but there are no kids at this party.

–

The combustion that propels the bullet—while not, properly speaking, an explosion in and of itself—is triggered by an explosion. A minuscule one: the detonation of the cartridge’s primer. That explosion is caused by the smack of the firing pin against the cartridge. It ignites the propellant, and the propellant pushes the bullet.

What causes the firing pin’s descent, of course, is the convulsive clenching of a human hand.

–

They’re not as young as they used to be: by midnight, the crowd has thinned. January’s still there, and so is Martin, and so is Jeff. In search of a place to sit, they’ve moved to the mostly empty carousel and claimed one of the carriages, really two ornately carved and gilded red-painted benches set facing each other. The boys sit together with January across, her feet tucked against the footboard and her knees between Jeff’s and Martin’s.

January’s coming down, and she’s pretty sure Martin is long grounded. It must be seriously cold outside; there was a frost warning, and the draft every time the doors open to let somebody else leave is bitter. She thinks she’ll be good to drive in another twenty minutes, anyway, and somewhere east of here her cats are probably picketing.

She’ll make her excuses after two more rounds on the carousel. The woman running it for the rental party is probably ready to go home to whomever she has, even if Martin has the place until one.

Besides, if January stays much longer, she’ll be stuck cleaning up.

The conversation has reached that point where they’re tidying up stray threads from earlier—like the end of a well-constructed movie—and Jeff has just finished telling them how the Yard Bunny defeated him as roundly as the Road Runner waxing Wile E. Coyote when she remembers something she was going to ask about earlier. Her research bump is itching: it’s a hazard of being a librarian.

“Did you ever find out what the backstory on the ghost plate was?” she asks.

“Backstory?” Jeff looks sleepy and contented, to the point where January is a little worried about him driving home. She doesn’t think he’s touched a drop of anything mood altering all night, however, which puts him on firmer ground than she and Martin, even if they’re both coming all the way back through sober and into a little cold and achy.

“You know.” She gropes dreamily after the right words. She has to raise her voice to be heard over the thump and blare of the band organ as they come around in the circle once more. They’ve been through its rolls—assuming they are rolls; the Internet tells her many band organs now run on MIDIs—so many times that she knows what order the songs come in now. She’ll be hearing them in her sleep.

One rank ahead of the red-painted chariot, the gray ponies—including the mismatched one—go up and down in little circles, riderless as horses in a funeral parade. “Provenance. History. Who put it there and where did it come from? That sort of thing.”

Jeff leans his head back, closes his eyes, and shrugs. “Houses are mysteries, and not all of those mysteries are nice things. Sometimes it’s best to not ask.”

Behind him, the brass ring glints in the dispenser, but January is so surprised to see it she doesn’t think to stand up and grab it until it has gone by. The carousel slows, song ending. She’d thought they were the only riders, but there must be somebody on the other side. Because when they come around again, the ring in the dispenser is just dull wire.

She’d swear the gray filly flicks its tail in annoyance, but of course it’s just a cold draft from the opening door. Somebody else is leaving the party for the long drive home.

–

Once the decision to fire the gun is made, the neural impulse to pull the trigger travels from brain to finger. Or possibly the action is reflexive. Possibly deep in the animal regions of the brain, electrical activity commences, leading the finger to convulse upon the trigger, the gun to discharge, and the mind—a few tremendously significant fractions of a second later—to justify the action to itself, believing it—I—has made a decision.

Or maybe those animal regions of the brain are part of its I, whether—culturally speaking—we are trained to regard them as such. Maybe those bits of ourselves that we alienate as subconscious impulses are as much I as the things Freud quantified as the ego and superego.

That I will provide reasons—motives, justifications, triggers. Jilted love or spurned advances. Money, sex, control. Any homicide cop can tell you those are the reasons people die.

In real life, it’s simple. The romance only happens in the movies.

–

All her best intentions of making a clean getaway evaporate, and January—of course—winds up staying behind to help clear. She and Martin and Jeff divide the spoils between them. Her share of the take includes a plate and a half of assorted cookies (unadulterated—January notes with a bit of pride that all of her brownies are gone), half of a tuna casserole, three deviled eggs, the heel of the saffron bread, and some shrimp dip. She won’t have to cook for a week.

She hopes none of the folks who left plates behind want them back, because she’s got no clue who brought what, or even who half the people in attendance were.

Behind her, the carousel sits empty and silent, even the Wurlitzer no longer breathing out its jangling tunes. The lanky Latina operator has been bagging trash and hauling it out to the dumpster. She seems overjoyed that some of the partygoers stayed behind to help tidy, and keeps shooting January shy thank-you smiles whenever their paths cross.

Actually, considering the crowd, the mess isn’t bad. January finds the brooms and dustpan behind the popcorn counter. While Martin starts cleaning out the popcorn machine, Jeff takes the big push broom, leaving January with the flat corn broom. She climbs onto the carousel platform and begins ferreting crumbs and paper wrappers from under chariots and between horses. She holds onto the pole that runs through a panda, leaning down to sweep between its paws, and the surreality of the moment strikes her.