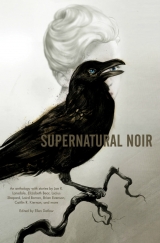

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

I make four stumbling steps toward the door before the jar shatters. Black clouds veined with fire and lightning roll forward, growing. The redhead with the gashes shrieks and hits her knees, and as I reach the door I can only watch as the cloud rears back like a snake and then strikes her, a tendril of black and red wrapping around her skull.

Her reaction is awful and instantaneous. Her body jitterbugs for a terrible, violent second, and then something flashes through her. When it’s done, she falls apart, ashes scattering across blood-spattered marble.

I run. More screams follow me, but they die one by one. Afraid of getting lost in Michael’s gigantic home, I return to the window and crawl out.

By the time I reach the Mercury, the snub nose still clenched in my fist and my lap slick with blood, the cloud has started billowing out of the mansion’s windows. Shelly tries to examine my wounds, but I yell at her to drive, just drive, goddamn it.

She speeds away from Michael’s home, and Hell follows.

–

Shelly walks me into the motel room—a flop worse than my place back in the city—and I sink onto the bed. I’m cold, freezing, and the only warm things in the room are Shelly’s hands against my face.

“It’ll be all right,” she tells me, and I’m happy she cares enough to lie.

“Maybe . . . for you.”

“Don’t say that.”

“I’ll say a lot more, babe.”

Her hands leave my face, and suddenly she’s busy ripping up sheets that have probably seen more sex than soap. “We just have to get you bandaged up,” she says.

“No!” The shout runs a spike of hot iron straight through me, and I scream.

Shelly freezes. “Baby?”

“You gotta go.”

Her lips tremble. I know what she wants to say.

“I can’t let . . . you die with me,” I tell her. “I’m not gonna make it, anyway. Besides, I . . . I did this so you could get free.”

Shelly stands there, tears running down her face, and I can tell she’s full of love. When she mashes her lips to mine, it’s the most welcome kiss I’ve ever received.

“I love you, baby.”

“I love you. Now go.”

She kisses me again and disappears out the door.

So that’s it. I listen for the Mercury’s engine, for the sound of tires peeling away over hot asphalt. When I hear it, when I know she’s safe, I close my eyes and listen for the other sound, that rumble that turns into a roar.

Soon, the light begins to flicker, only this time it’s nothing in the room. It’s the sun. Everything shudders.

As I wait for Hell to arrive, I think of Shelly, of her pale skin and dark curves. I think of what I’ve done for her, and I think of everything I’d do if I could, and the last blister on my heart breaks.

–

Nate Southard’s books include Red Sky, Just Like Hell, Broken Skin, He Stepped Through, This Little Light of Mine, and Focus, which was co-written with Lee Thomas. His short fiction has appeared in such venues as Cemetery Dance, Thuglit, and the Bruce Springsteen–inspired anthology Darkness on the Edge. Nate lives in Austin, Texas, with his girlfriend and numerous pets. He loves food, cigars, and muttering under his breath. Look him up at NateSouthard.com.

| THE ABSENT EYE |

| THE ABSENT EYE |

Brian Evenson

–

I

I lost my eye back when I was a child, running through the forest as part of some game or other. At the time I was with two other children, a boy and a girl, a brother and a sister, neither of whom I knew, or, indeed, had even seen before. It was one of them, the skinny shoeless boy, who suggested the game. I cannot now remember much about it, only that when I lost the eye I had been giggling and chasing the girl, and was also being pursued by the boy. In my flight, a thin, barbed branch snapped back and lashed like a wire, slashing a deep scar across my nose and tearing the eye itself free of the socket to leave it unseeing and ruptured on my cheek.

I do not remember exactly how I got home. Perhaps the boy and girl took me, perhaps they carefully led me home and rang the bell before fleeing, but nobody had seen them do so and this was not, in any case, what I remembered. All I remembered was standing stunned in the forest, feeling what was left of my face, and then suddenly and without transition being home again, standing just before my front door.

There was, a doctor informed me, no choice but to remove the eye, which was, for all intents and purposes, already removed. At first they left my socket exposed—to allow the wound to heal, I suppose. The optic nerve, confused, continued to collect information, sending my brain random, broken flashes of light.

Later, I was issued a patch, a cheap cotton affair dyed black and affixed with an elastic band. If the patch got wet, its dye would bleed, staining a black circle around my eye and, when wet enough to seep through, within the socket itself. I wore this patch for several months, continuing to see flashes of light when I removed it. At times these cohered into something that gave the semblance of an image. Through my remaining eye I would see the real world around me—would see, for instance, the solitary and spare confines of my bedroom, the even line of the top of my dresser and, above it, the even line of the ceiling. But the optic nerve would impose upon this other, twisting shapes, initially incomprehensible in form and aspect but, as the weeks and months went on, slowly becoming more articulated.

When I told the doctor what I saw, he just shook his head at me as if I were a fool. And yet even as he did so, I could see a smoky and blurred figure congealing around him. A floating figure which, as I watched, resolved into clarity and revealed itself to be his bloated double. It looked not unlike the doctor, though its legs faded into the air as indistinct smoke. It floated there, for a moment clear, and then hard to discern, and then clear again. It had something like an arm wrapped tight around the doctor’s shoulder. Its other hand, I saw, was at his throat. As I watched, the hand tightened.

The doctor, unaware of the creature itself, touched his throat and coughed. I watched his double smile and let go. I threw up my hands in surprise, much to the doctor’s puzzlement, and that was when the creature clinging to him turned and stared. It saw me, and knew it was seen by me. Both of us remained motionless, waiting for what the other would do. And then, very slowly, I watched its blurred mouth stretch into a grin.

–

A few months later, my parents were surprised when I declined to have a false eye fitted into my empty socket. What I had understood, what they would never understand, was that there was still an eye of sorts there, one that saw exceedingly well, but just not in the fashion other eyes saw.

At first, I kept my socket blinkered, covered by the patch, hoping not to see the creature I had seen before. But one night, afflicted with curiosity, I lifted the patch.

I was alone in my room, one lamp burning fitfully in the corner, shadows dancing along the wall. I wanted to see if the shadows themselves were something more, thinking that if they were I would turn the lamp up and drive them away. There was nothing there. Or nothing in the shadows, rather. But when I looked down, I saw a thin, smoky, long arm grasping my waist. A face that was a parody of my own floated just inches away, staring into my empty socket.

I shuddered. A gleam came into the creature’s eye, but just as quickly faded, though it continued to regard me with what might be described as curiosity. It opened its mouth and I watched its lips and tongue, such as they were, operate in a semblance of speech.

I could not hear words, but I tried to follow the movements of its lips. “You can see me,” I believe it must have said, or else it was, “You can’t be me,” unless it was something else. I quickly lowered the patch so as to blot it out. There immediately followed a tightness in my throat that I tried to see as natural, that I tried to ignore, and then I found myself briefly choking. I ignored this until I felt a stabbing pain in my chest, and lifted the patch to find the creature had insinuated its hand beneath my ribs, had its fingers apparently wrapped around my heart. When it saw that I was looking, it let go and smiled.

“What is it?” I asked. “What do you want?”

It pointed languidly to its ear, then pointed to my own, then said something that I could not hear. When I did not respond, it did this again, and again, until finally, not knowing what else to do, I nodded as if I had understood. Its smile grew wider. Slowly it wriggled its way up my torso until its head was just beside my own. And then it stabbed its finger deep into my ear again and again until I screamed in pain and lost consciousness.

–

II

For fifteen years they kept me confined—for my own protection, they claimed. My parents, alerted by my screams, had climbed the stairs to find me writhing on the floor, blood leaking from one of my ears. Though they could not find the needle or pencil or other implement that I had used to pierce my own eardrum, they did not doubt that I had done this to myself. I only worsened matters by trying to be honest first with them and then with the medical profession, but after all I was young. At the time I hardly knew that the world does not operate through directness and honesty but by way of falsehood and deception. Thus I remained adamant and insistent about what had happened, describing the creature and what it had done to me, not realizing how I was tightening the noose around my own neck.

In the place of my ruined eardrum there grew another sort of ear, one that could hear that which could not, properly speaking, be heard. The creature that clung to me began to speak to me as well, its voice not a voice exactly, but a kind of whispery echo, not always easy to make out, more a suggestion of a voice than a voice itself.

At first I resisted the creature, tried to ignore it, tried to pay no attention as it squeezed my heart or upset my belly or bore down on my lungs. I would hold out as long as I dared, keeping the patch over my eye and stopping my ear with whatever came to hand—a scrap of wet fabric, chewed paper, bits and scraps of food—but it persisted. Eventually I could feel its fingers stroke the fibers of my brain, exciting them into a kind of panic that brought the orderlies running, and like as not got me straitjacketed or sedated. Once I was subdued, they cleaned me up, picked the bits out of my ear, and then the creature could speak to me while I, restrained, could do nothing to resist. What did it want of me? It could not hear me, but it knew I could hear it and seemed to have a need to communicate. You will be of use, friend, it most often said. “Of use how?” I asked, raising pained looks among the orderlies who saw this as nothing but a man speaking to himself. You must not fight, it said. You must give yourself over, friend. Listen and watch and wait, and later on you shall know.

With the additional confusion of the injections and shock treatments and straitjacketings, it took the creature and me years to settle into an uneasy sort of truce. For one thing I learned that though it could cause me pain, though it could excite me, it could not do much more, could not kill or damage me permanently without my permission, and as time went on I learned to control my responses to it. For another, I realized that when my ear was unplugged I could hear not only its whispers, but beneath them, lower and farther away, other sounds humans could not hear.

It was this that finally got me spending a few hours of the day with my patch rolled higher up on my forehead, peering through my empty socket. What I saw at first surprised me, though it should not have. I had long assumed that the smoky creature that had come to me had been the same creature I had seen torturing the doctor, that it was one of a kind, and that it had, by leaving the doctor and coming to me, begun to take on my own characteristics. But what I saw now was a similar creature clinging to each person around me, a whole world of trailing ghosts. They assumed all postures, some of them simply clinging loosely to the bodies of their hosts, others coiled murkily around them. With some of the mad, the creatures seemed malicious, their smiles unholy and their fingers wedged deep into their host’s brains. With others, the creatures seemed to be wailing and crying, trying as well as they could to extricate themselves from the person to whom they were attached. But as they worked one part of themselves free, another smoky strand would form and attach. The orderlies had them as well, though their creatures were generally calmer, though perhaps more inclined to enjoy violence when it did happen. The doctors had them too. Indeed, I began to realize, these creatures perhaps had no choice but to be with us. They were in some sense imprisoned. We were part of them and they were part of us.

This was a terrible thing to know and I fought it as long as I could. I finally got used to it because there was no other choice, at least not one that I could see. I was like everyone else, with one exception: I knew.

–

III

And then, late in my confinement, I found myself awoken by a slow, steady whispering. Friend, it said. Get up, friend. Friend, get up. It repeated the same words over and over again, and kept at it until, finally, I arose.

“What is it?” I asked, but in the dark my double could not read lips. And so I stood and switched on the light, then lifted my eye patch and repeated my question.

The creature curling around me seemed anxious, though I could not understand why. It regarded me as I spoke again and then nodded curtly. Out the door, it said. When I stood waiting, it repeated its command again, adding, in a more gentle whisper, Friend, I will lead you.

And indeed it did. The door, I was surprised to find, was unlocked. We went out the door, and then down the hall and past a sleeping orderly whose own creature had its fumid hands plunged deep within the man’s skull, and who nodded and broke into a saurian smile as we passed. Another turning and then another, and then to the door of another inmate’s room. This too, I was surprised to discover, was unlocked.

I went inside and closed the door behind me. Turn on the light, my creature said to me, and so I did. Sit in the chair, my creature said, and so I did, further drawing it close to the bed when he so commanded.

The man in the bed was an older inmate, a man who had been old even when I had first arrived. The little hair he had left was like a haze around his skull, the flesh liver-spotted and his forehead pale. Uncover him, my creature said, and I did, and saw that he lay there with his skin loose and unhealthy, looking all but dead. His creature was wound around him but losing shape, resembling him less and less. And when I leaned closer to the man his creature hissed, more like the double of a snake than that of a man.

I turned toward the creature wrapped around me, regarded it questioningly. Watch, it suggested. And so I turned back and watched.

With my physical eye alone I would have missed the transition. There was little to tell me physically when the man died. But with the other eye, the missing one, I could see his death happen. Not because of the man himself, but rather because of his creature, for as he approached death he grew smaller, less and less distinct, until he was little more than a shadow. And then, suddenly, he dropped out of existence altogether.

Where does he go? my creature wanted to know. Why does he leave? What becomes of him? I thought at first he meant the man himself, as I would have meant, but as he continued to speak on, whispering away in a susurrating language that seemed at once identical to and absolutely distinct from my own, I realized that it was the man’s creature he was asking about. To him the man meant nothing, but the disappearance of the creature meant everything, for in it he foresaw the disappearance of himself.

I tried to talk to my creature, tried to console it with the so-called wisdom we humans use when facing the knowledge of our own death. But my words were too complex for it to be able to read them well from my lips and the creature grew quickly frustrated and dissatisfied. So I took pencil and paper and began to write words out for it, but when I blinked my human eye I realized that what I saw as words the creature saw as much less, as hardly marks as all. Indeed, to make words it could understand, I had to trace the words over again and again, and flourish them. Only then, once the paper seemed to my good eye an inextricable maze of lines, did it read to my absent eye as words.

What the creature had gained from its proximity to my mind that allowed it to read my tongue I don’t know, but when I first started to trace, it became interested and I saw it startle with recognition when at last the words were revealed. Yet it took me long enough to do my trace work that by the time I finished, my purpose was no longer the same as when I had begun. Rather than telling the creature something along the lines of It is vain to shrink from what cannot be avoided or Take consolation in the fact that he lives on in your memory or Surely there is a life beyond this one, I found myself laboriously creating through my words—first over the course of hours, then over the course of days, and finally over the course of a lifetime—a lie that would allow me to lead a different sort of life.

–

IV

What did I write? It hardly matters now. I wrote what I had to write to convince my creature to aid me in shaking my way free of the institution, and then engraved my lie over and over again with stroke after stroke of the pencil until the creature too could read it.

What I wrote was in essence an offer of help. I did not know where the other creature had gone, I claimed, but if anyone could find out, I said, it was I, someone with a foot in both worlds. I was willing to search, willing to try to find out. I was, I lied, a sort of detective. If he would only agree to aid and assist me, he had my promise that I would dedicate my life to finding the answer to his questions, questions that I privately figured from the very beginning to be unanswerable.

And thus it was that we entered into a kind of compact in which, by pretending to be a detective, I in fact became one. We agreed that for me to be able to answer his questions, I would have to have a free hand, so to speak. Arrangements were made among the various creatures attached to those confined to the asylum, such that at the end of another month I found the right doors left open to me and a series of sleeping guards along my path. With the help of my creature, I walked unimpeded out of the sanitarium and never looked back.

In the years that followed I traveled the earth, looking, searching, for any sign of what might become of a creature when its host died. I have learned little, perhaps nothing. I have played the role of detective, and have gotten my hands dirty. I have stood among the tombs of the dead looking for wisps of smoke to arise or fall that might be the remnants of the creatures. I have lain on my back wrapped deep in furs, staring up at the northern lights and wondering if the glow might not be their unearthly remains. I have stood late at night in the wards of the comatose, watching drowsy figures swaying gently above motionless bodies. I have shot a man in order to witness the moment of his death. I have poisoned a man and attempted to capture the creature wound around him in a bottle before it could disappear. All to no avail.

But the majority of my life has not been spent nearly so romantically. These moments are the exceptions rather than the rule. What I most often do, day after day, is await the moment when my creature begins to direct my footsteps, leading me to a new corpse. Once there, I make notes of the scene and then interview, with the help of my creature, any others close enough to have seen the moment of death. Name? I used to begin, but came quickly to realize that this is not a word they understood. So instead it became, What happened? What did you see? Was there any hint of where he went? And so on. And then I search for clues, strangenesses in the scene of the crime, disturbances visible only to my missing eye. I write down the responses and record whatever clues I find or pretend to find all in the overlapped script that they can read, and then I take the pages and I leave them pinned to trees and pasted to walls, crumpled beneath bridges, secured in trash bins. What becomes of them then, I do not know.

The irony is through this process, unearthly though it is, I might learn enough to know if a man has been murdered, and even have some sense of who his killer is. I often acquire sufficient information to make a call to the police, give them a nudge or two in the right direction. I do not know how many crimes, in how many countries, have been solved by me, how many criminals brought to justice, but I suspect there have been many.

But as to the matter of where our creatures go upon our death, I find myself no closer to having an answer than I was when I first began. My investigation, admittedly, began as a ruse, but as time has gone on I find I cannot help but go from miming the detective to taking on this investigation in earnest. I grow older and more discouraged, but my creature remains hopeful, optimistic. It insists that I keep on, that I continue to drag my way across the earth, and no doubt it will so insist until I am dead, until all that remains of me are the words I have written here.

–

I am writing this not in the overlapped and baroque letters that have become second nature to me, but in the normal human way, as ordinary letters on an ordinary page. Mostly I feel there is no point writing this. Nothing will come of it, I know, and any who read it can only think me mad. But I do not know what else to do.

My creature curls in the air beside me, regarding me with curiosity but saying nothing, at least not yet. Soon it will demand to know what I have inscribed on the paper and why it cannot read it; I hope to have finished before then.

Soon I must move on. But until then, I will finish my account and then sit here, hand idly moving, pretending to write. Until I feel my creature’s hand tight on my throat and its words forming in my ear, and know that I must once again haul myself to my feet. And then I will continue my wandering, a lone and failed detective in the employ of someone not quite myself, but not quite other, either.

–

—for Michael Cisco

–

Brian Evenson is the author of ten books of fiction, most recently the story collection Fugue State and the novel Last Days, which received the American Library Association’s Award for Best Horror Novel of 2009. His novel The Open Curtain was a finalist for an Edgar Award and an International Horror Guild Award and was among Time Out New York’s top books of 2006. Other books include The Wavering Knife (winner of the IHG Award for best story collection) and the tie-in novels Aliens: No Exit and Dead Space: Martyr. He has received an O. Henry Award, as well as an NEA fellowship. He lives and works in Providence, Rhode Island, where he directs Brown University’s creative-writing program.

| THE MALTESE UNICORN |

| THE MALTESE UNICORN |

Caitlнn R. Kiernan

–

New York City (May 1935)

It wasn’t hard to find her. Sure, she had run. After Szabу let her walk like that, I knew Ellen would get wise that something was rotten, and she’d run like a scared rabbit with the dogs hot on its heels. She’d have it in her head to skip town, and she’d probably keep right on skipping until she was out of the country. Odds were pretty good she wouldn’t stop until she was altogether free and clear of this particular plane of existence. There are plenty enough fetid little hidey holes in the universe, if you don’t mind the heat and the smell and the company you keep. You only have to know how to find them, and the way I saw it, Ellen Andrews was good as Rand and McNally when it came to knowing her way around.

But first, she’d go back to that apartment of hers, the whole eleventh floor of the Colosseum, with its bleak westward view of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades. I figured there would be those two or three little things she couldn’t leave the city without, even if it meant risking her skin to collect them. Only she hadn’t expected me to get there before her. Word on the street was Harpootlian still had me locked up tight, so Ellen hadn’t expected me to get there at all.

From the hall came the buzz of the elevator, then I heard her key in the lock, the front door, and her footsteps as she hurried through the foyer and the dining room. Then she came dashing into that French rococo nightmare of a library, and stopped cold in her tracks when she saw me sitting at the reading table with al-Jaldaki’s grimoire open in front of me.

For a second, she didn’t say anything. She just stood there, staring at me. Then she managed a forced sort of laugh and said, “I knew they’d send someone, Nat. I just didn’t think it’d be you.”

“After that gyp you pulled with the dingus, they didn’t really leave me much choice,” I told her, which was the truth, or all the truth I felt like sharing. “You shouldn’t have come back here. It’s the first place anyone would think to check.”

Ellen sat down in the armchair by the door. She looked beat, like whatever comes after exhausted, and I could tell Szabу’s gunsels had made sure all the fight was gone before they’d turned her loose. They weren’t taking any chances, and we were just going through the motions now, me and her. All our lines had been written.

“You played me for a sucker,” I said, and picked up the pistol that had been lying beside the grimoire. My hand was shaking, and I tried to steady it by bracing my elbow against the table. “You played me, then you tried to play Harpootlian and Szabу both. Then you got caught. It was a bonehead move all the way round, Ellen.”

“So, how’s it gonna be, Natalie? You gonna shoot me for being stupid?”

“No, I’m going to shoot you because it’s the only way I can square things with Auntie H., and the only thing that’s gonna keep Szabу from going on the warpath. And because you played me.”

“In my shoes, you’d have done the same thing,” she said. And the way she said it, I could tell she believed what she was saying. It’s the sort of self-righteous bushwa so many grifters hide behind. They might stab their own mothers in the back if they see an angle in it, but that’s jake, ’cause so would anyone else.

“Is that really all you have to say for yourself?” I asked, and pulled back the slide on the Colt, chambering the first round. She didn’t even flinch . . . But, wait . . . I’m getting ahead of myself. Maybe I ought to begin nearer the beginning.

–

As it happens, I didn’t go and name the place Yellow Dragon Books. It came with that moniker, and I just never saw any reason to change it. I’d only have had to pay for a new sign. Late in ’28– right after Arnie “The Brain” Rothstein was shot to death during a poker game at the Park Central Hotel—I accidentally found myself on the sunny side of the proprietress of one of Manhattan’s more infernal brothels. I say accidentally because I hadn’t even heard of Madam Yeksabet Harpootlian when I began trying to dig up a buyer for an antique manuscript, a collection of necromantic erotica purportedly written by John Dee and Edward Kelley sometime in the sixteenth century. Turns out, Harpootlian had been looking to get her mitts on it for decades.

Now, just how I came into possession of said manuscript, that’s another story entirely, one for some other time and place. One that, with luck, I’ll never get around to putting down on paper. Let’s just say a couple of years earlier, I’d been living in Paris. Truthfully, I’d been doing my best, in a sloppy, irresolute way, to die in Paris. I was holed up in a fleabag Montmartre boarding house, busy squandering the last of a dwindling inheritance. I had in mind how maybe I could drown myself in cheap wine, bad poetry, Pernod, and prostitutes before the money ran out. But somewhere along the way, I lost my nerve, failed at my slow suicide, and bought a ticket back to the States. And the manuscript in question was one of the many strange and unsavory things I brought back with me. I’ve always had a nose for the macabre, and had dabbled—on and off—in the black arts since college. At Radcliffe, I’d fallen in with a circle of lesbyterians who fancied themselves witches. Mostly, I was in it for the sex . . . But I’m digressing.

A friend of a friend heard I was busted, down and out and peddling a bunch of old books, schlepping them about Manhattan in search of a buyer. This same friend, he knew one of Harpootlian’s clients. One of her human clients, which was a pretty exclusive set (not that I knew that at the time). This friend of mine, he was the client’s lover, and said client brokered the sale for Harpootlian—for a fat ten percent finder’s fee, of course. I promptly sold the Dee and Kelley manuscript to this supposedly notorious madam who, near as I could tell, no one much had ever heard of. She paid me what I asked, no questions, no haggling—never mind it was a fairly exorbitant sum. And on top of that, Harpootlian was so impressed I’d gotten ahold of the damned thing, she staked me to the bookshop on Bowery, there in the shadow of the Third Avenue El, just a little ways south of Delancey Street. Only one catch: she had first dibs on everything I ferreted out, and sometimes I’d be asked to make deliveries. I should like to note that way back then, during that long, lost November of 1928, I had no idea whatsoever that her sobriquet, “the Demon Madam of the Lower East Side,” was anything more than colorful hyperbole.

Anyway, jump ahead to a rainy May afternoon, more than six years later, and that’s when I first laid eyes on Ellen Andrews. Well, that’s what she called herself, though later on I’d find out she’d borrowed the name from Claudette Colbert’s character in It Happened One Night. I was just back from an estate sale in Connecticut, and was busy unpacking a large crate when I heard the bell mounted above the shop door jingle. I looked up, and there she was, carelessly shaking rainwater from her orange umbrella before folding it closed. Droplets sprayed across the welcome mat and the floor and onto the spines of several nearby books.