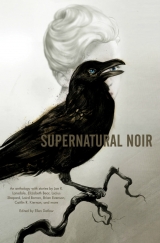

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

I say, “Easy, Greg.”

“Even if we get there, which we won’t, and find the place empty, which we fucking won’t, we’re gonna do what? Set up a happy house and then dump the shit in the lake? At the same lake we’re staying at? Nice. They’d never find that shit, right?” Greg’s voice goes higher and louder, getting shrill, his face turning red.

I turn around because I want to actually see Mike punch him instead of watching it in the rearview mirror. And then Greg’s voice cuts out, mid-rant. He looks at us, mouth open, eyes wide, and his face crumbles, slides away, like something broke, and I turn back around fast, because, that look on his face, I can’t watch that, can’t, and whatever happens next will be better seen from the safety of my rearview mirror.

So now I’m looking in that glass and I’ve lost Greg. Can’t find him. Then he’s there again, and he flickers. In and out of the mirror. He’s not moving. He flickers like a goddamn light bulb.

I turn back around. Greg’s throat is gone. It’s all just red pulp. Blood leaks out of Greg’s eyes, nose, and ears, and his mouth is open and keeps opening, a silent scream, and how does his mouth keep going like that? And his eyes opening too, the whites gone all red, then worse than a scream, this horrible whisper from his ruined throat, a hiss, a leaking of air, and he winks out. No more flickering light. Blood mists the rear passenger window and Greg’s seat, but he’s not sitting in the back seat. He’s not there. He’s gone.

Mike screams Greg’s name and kicks and punches the back of my seat, the door, the ceiling. I turn back around and I’m doing ninety, didn’t realize it, and am about to plow into the back of a tractor-trailer. I brake and swerve onto the shoulder, rumble strip, then grass and dirt, and manage to stop the SUV. Mike is still screaming. I look at the dash, the speedometer reading zero, the road, but don’t really see anything other than Greg’s face, before . . . before he what?

I yell to Mike: “Before he what? Before he what?”

“I don’t know, Danny. Just go. Just keep driving.”

“What?”

“Keep fucking driving. Just keep driving, keep driving . . .” Mike repeats himself and keeps on repeating himself.

I want to dive out of the car and run away and keep running. But I don’t. I listen to Mike. I drive. Pull off the shoulder and onto the highway. I keep driving, and try not to look into the rearview.

–

Overcast. The clouds are low and getting lower. North on I-91 and Mike sits in the middle of the back seat, filling my rearview. He watches himself. Making sure he’s still there, maybe. I’m watching him too, him holding Henry’s sawed-off shotgun. Every few minutes his hands get to shaking. The gunmetal vibrates in his hands.

I’ve tried slowing down, pulling off the road or into seemingly empty rest areas, but Mike won’t have it. He threatens to shoot me in the head if I stop. Says that I have to keep driving. Keep going. I keep going, more because I’m scared, and don’t know what else to do. I know Mike won’t shoot me, would never shoot me. Still.

“Hey, Mike.”

“Still here.”

“Need to think about this. Back at the pawnshop. Did that old guy shoot Henry?”

“It happened so fast. He jumped up with that gun pointed at us and . . . I can’t remember, Danny.”

“Did he shoot Greg, too?”

Mike shakes his head, and it turns into a shrug of the shoulders, and that turns into his hands shaking all over again.

I don’t ask Mike if he thinks what happened to Greg happened to Henry. I don’t ask Mike about the three gunshots I heard. I don’t ask Mike if he thinks what happened to Greg will happen to him. I know Mike’s answer to the questions. And I know mine.

We cross the border, into Vermont. Things feel kind of funny in the car. The air all wrong. Too light. Or too heavy.

Mike says, “Remember that one summer your grandma let me come up to the lake house?”

“What? Yeah, of course I remember. Grandma never called to run it by your mom and you didn’t tell your mom you were going and by the time we got back the cops had put up posters on half the telephone poles in Wormtown.”

Mike breathes through his nose. Almost sounds like a laugh. He says, “That was the first time I’d ever been in Vermont. This is my second.” I watch Mike talking in the rearview mirror. Maybe if I focus hard enough on watching him, he won’t disappear.

“You need to get out more often.”

“Henry or Greg ever go up?”

“Fuck, no. Greg would’ve burnt the place down just trying to make toast. Just you, man. And Grandma didn’t know about Henry.”

“She knew. She told me we shouldn’t be spending time with a stranger in the neighborhood that much older than us. She told me it wasn’t right.”

“When did she tell you that?”

“At the lake house. It was the only time she talked to me the whole week up there.” Mike laughs for real this time. “I loved it up there, Danny. I really did. But man, it was really weird too. Your grandmother would cook us meals and make our beds, but I remember her not talking much at all and spending most of the week by herself, smoking her Lucky Strikes on the dock, going for walks by herself, leaving us alone.”

I say, “She did the same shit back home.” Grandma fed us but would kick me and Joe out of the apartment until it got dark out, and Joe would usually go off on his own, not let me come with him. If it was raining or something and we couldn’t go out, she’d stay in her room with a book or her little black-and-white TV. Away from us.

“I’m not feeling right, Danny.” Mike rubs a forearm across his forehead. Doesn’t let go of the gun. His voice sounds smaller, farther away, coming from another room.

“We’re almost there, Mike.” I say it without thinking. I don’t know what to do.

“I know your grandma ignored us all at your home. But it was different up there, all by ourselves, away from the city and everything. Up there, I really noticed it. I got up earlier than you and your brother a couple of mornings and spied on her. She’d just stare into the mountains or into nowhere, really. It was like we weren’t even there, Danny. I’m getting fucking worried; maybe we were never there. Oh shit, Danny, I don’t feel right.”

“I’m pulling over, Mike. You relax. Keep talking to me.” We’re only ten miles from the exit, not that it matters. I slowly pull over onto the shoulder and I want to believe that if we just get out of the car, then we’ll be okay; he’ll be okay. But there were three shots.

Mike’s eyes are closed and he’s concentrating hard on something. Brow folding in on itself, upper lip shaking like an earthquake. He says, “Don’t know how she could ignore you and Joe fighting the way you did. You fought over everything. Made me feel really, I don’t know, uncomfortable. That probably sounds messed up coming from me. But, I don’t know, man, it just didn’t feel right. Wanted to kick both your heads in by the end of the vacation.”

“Wish you were here, send us a postcard, right? Mike, listen, the car is stopped. We’re going to get out. Just walk around. Get some fresh air, all right?” I say, then I lie to him: “It’ll help.”

“What was the name of the card game you guys always played?”

“Cribbage. Joe always tried cheating me on the counts.”

“Nah, you were just too dumb to count the points right and Joe would call you on it and . . .” Mike stops talking and slow fades out.

I scream his name and he comes back. He looks like Greg did. Bleeding from everywhere. There’s a dime-sized hole in his forehead, and it’s growing. He opens his mouth but can’t speak.

I call his name, not that his name works anymore, right? I ask him if he’s still with me. I ask him to say something.

Mike whimpers like a goddamn dog that just had his leg stepped on, and he slides across the back seat, out the door and onto the shoulder of the highway, carrying the shotgun.

I get out, sprint around the front of the car, my own ears ringing, but not because of the cuff in the head he gave me forever ago. Mike stumbles, turns around aimlessly, his feet lost in a circle. His eyes are rolled back in his head. He puts the barrels of the sawed-off in his mouth. He pulls the trigger and disappears. He disappears and pulls the trigger. Which came first? Fuck if I know, but there’s nothing left of him but a fog of blood, and the shotgun drops to the pavement after hovering in the air for an impossible second.

–

Earlier, after telling Greg and Mike my getaway plan, I was more than a little worried that I wouldn’t remember how to get to the lake house. But I remember. Every turn.

I’m not feeling so great. Don’t know if it’s because I watched Greg and Mike (and goddamn Henry, I saw him flicker in the rearview, in the dark too, you betcha) and I only think I’m feeling what they were feeling. Joe always said I was nothing but a follower. Fucking Joe.

So there’s that, and now I’m thinking about the shots I heard. Did I hear three? Or was it four? The first two came in a quick burst, one right after the other, piggybacking. Then a pause. Then a third. But it could’ve been three shots in that quick burst. And how long was that pause? I really can’t remember now.

I drive down the long dirt road. I’m the only one out here. Within sight of both lake and house there’s a small chainlink fence across the road. I plow through it and park next to the house. The white shingles have gone green with mold. The roof is missing tiles and tar and is sunken in parts. The screened porch is missing its screens. If a house falls apart in the woods and nobody’s there, will anyone miss it?

This is where I spent so many quiet and solitary summer weeks with Grandma and Joe, but not really with them. Joe painted, and she smoked and walked. This place here, this is where I learned to hate them.

In Wormtown, it was different. I had Mike and Henry. I kept busy and didn’t have time to think about how fucked up it all was. I miss Mike. Really miss him already, like he’s been gone for years instead of minutes.

Now that I’m here, I’m afraid of the house. Like if I stare at the porch too long, I might see Grandma there, sitting in a chair, looking out over the lake, seeing whatever it was she saw, and smoking those Lucky Strikes. And what if now, right now, she finally turns to look at me, to see me?

I spin the car around, and park it so I’m facing the lake instead of the house. It doesn’t help. I feel the house and Grandma somewhere behind me.

Not sure if I’ll get reception out here, but I take my cell out and call Joe. It goes through. He picks up, says, “Hey.”

“Hey.”

We don’t say anything else. We sit and stew in the quiet. It feels, I don’t know, thick. Like it always has. I’m thinking Joe maybe feels it too. What’d Mike say? Being around me and Joe was uncomfortable. Sounds about right.

He says, “What do you want now, Danny? You want to borrow money that I don’t have? Bail you out of jail again? Go call Henry if that’s it.”

“Joe,” I say. “Hey, Joe. I got something to tell you. It’s important.”

I pause and imagine what Henry, Greg, and Mike felt after they were shot, and before they disappeared. “Hey, Joe,” I say again. “Listen carefully. I’m up in Vermont, at the old place.”

I roll down my window. Goddamn, it’s cold out. Like I said earlier, didn’t wear the right clothes for this. Just a brown flannel and some black jeans, steel-toed boots laced to the ankle. Still no jacket, and I left my black hoodie at the apartment. Too bad all that stuff I left behind won’t just disappear like they did. Like I might. Three shots or four.

Winter is coming early.

“What?”

“Yeah. I’m here, by myself, Joe. The place looks fucking terrible. Rotting away to nothing.”

“What are you doing up there?”

“I don’t know. Trying to get away, I guess. Can’t, though. Doesn’t matter. I’m here, and I decided to call you. Because I’m thinking I should’ve told you something a long time ago. You listening? Here it is: Fuck you, Joe.”

I drop the phone. It disappears somewhere below me. The black gloves I’m still wearing don’t keep my hands warm. I rub my hands together, and I slouch into the seat. I’m not feeling good at all. Things getting heavy. Lake getting blurry.

The shotgun is on the seat next to me. I might pick it up, and then fade away.

–

Paul G. Tremblay is the author of the novels The Little Sleep and No Sleep till Wonderland, both of which feature narcoleptic private detective Mark Genevich; the short speculative-fiction collections In the Mean Time and Compositions for the Young and Old; and the novellas City Pier: Above and Below and The Harlequin and the Train. His stories have appeared in Weird Tales, The Last Pentacle of the Sun: Writings in Support of the West Memphis Three, and Best American Fantasy 3. He served as fiction editor of ChiZine and as coeditor of Fantasy Magazine. He is also the coeditor of the Fantasy, Bandersnatch, and Phantom anthologies with Sean Wallace, and of Creatures! with John Langan. Paul is currently an advisor for the Shirley Jackson Awards. He still has no uvula, but plugs along, somehow. More information can be found at PaulTremblay.net and TheLittleSleep.com.

| MORTAL BAIT |

| MORTAL BAIT |

Richard Bowes

–

When I think of death, what comes to mind is the feel of an ice-cold knife racing up my leg like I’m a letter being sliced open. When that happens in my nightmares I wake up. In real life, just before the blade of ice reached my heart, the medic got to me where I lay in that bloody field at Aisne-Marne, tied and tightened a tourniquet above my left knee and stopped the flow before all my blood ran onto the grass.

–

That memory of my war came out of nowhere as I sat in my little office in Greenwich Village on a sunny October afternoon. It felt like someone had riffled through my memories and pulled out that one. Beings that my Irish grandmother called the Gentry and the Fair Folk walk this world and can do things like that to mortals. A shiver ran through me.

My name’s Sam Grant and I’m a private investigator. Logic and deduction come into my line of work. So do memory and intuition. My grandmother always said a sudden shiver meant someone had just stepped on the spot where your grave would be.

I could have told myself it was that or a stray draft of cold air. But I’d felt this before and knew what it meant. Some elf or fairy had shuffled my memories like a card deck. And that wasn’t supposed to happen to me.

At that moment I was writing a letter to my contact, Bertrade le Claire. It was Bertrade who had worked a magic to shield me.

An intruder would see her image, her long dark hair, beautiful wide eyes—a face that seemed like something off a movie screen. She wore a jacket of red and gold and a look that said, “Step back!” She was a law officer in the Kingdom beneath the Hill.

The letter I was writing concerned new clients, the Beyers, a couple from Menlo Park, New Jersey. He worked for an insurance company; she taught Sunday school. In my office, she talked, he studied the photos I keep on my wall, and they both clung to hope and the arms of their chairs.

They were the parents of Hilda, a junior at Rutgers and currently a missing person. Hilda, who, according to her mother, was a sensitive girl who wrote poetry, was due to graduate in June of 1952 and become an English teacher. She’d had a few boyfriends over the years, but nothing serious as far as anyone knew. Not the kind of young lady to run off on a whim. But four months back, it seemed that she had.

While his wife talked, Mr. Beyer looked at the signed photo of Mayor La Guardia with His Honor mugging for the camera as he shook my hand and thanked me for civilian services to New York City during the Second War to End All Wars.

The one where I’m getting kissed by Marshal Foch, I leave in the drawer, because some guys in this neighborhood might get the wrong idea.

But I display Douglas MacArthur, executive officer of the Rainbow Division in 1918, pinning a Distinguished Service Cross on the tunic of a soldier on crutches. I’m not that easy to make out. But Colonel MacArthur, with his soft cap at a jaunty angle and a riding crop under his arm, you’d recognize anywhere. I figure it’s got to be worth something that I served under Dugout Doug and lived to tell about it.

Mrs. Beyer told me how the New Jersey cops couldn’t find a lead on Hilda. After other private eyes struck out, my name came up.

Mrs. Beyer paused, then said, “We have heard that she could have gone to another . . . ,” and trailed off.

“. . . realm,” I offered and she nodded. “It’s possible,” I said. Mr. Beyer’s eyes widened at hearing a man who’d been decorated by MacArthur say he believed in fairies.

After that we closed the deal quickly. My initial fee is $250. It’s stiff, but I think I’m worth it, especially since I wore my good suit and a fresh starched shirt for the occasion. I didn’t promise them their daughter back. I did promise I’d do everything I could to find her. On their way out, I shook hands with him. Put my left hand on hers for reassurance.

Playing baseball as a kid, I was a switch hitter, and I could field and throw with both my right and my left. I even learned to write with either hand. These days, the left’s the only thing about me that still works the way everything once did. And I tend to save it for special occasions.

In the Beyers’ presence I walked tall. But I still have metal fragments in my knee. With the clients gone I limped a bit on my way back to the desk.

I took a sheet of paper and a plain envelope out of the desk, stuck in a high-school-yearbook photo of Hilda, scribbled a few lines about the case, dated and signed it. Then I felt the intrusion and added the P.S.: “Some stray elf or fairy just got into my memories.” On the envelope I wrote Bertrade’s full name and her address in the Kingdom.

The phone rang and a woman said, “Sam,” and nothing more. She sounded tired, flat.

“Annie.” Anne Toomey is the wife of my buddy Jim. He and I were in France together. “How’s Jimmy?” Since she was calling I knew the answer. Knew what she was going to ask.

“Not feeling great, Sam. We wondered if you could handle the Culpepper case today.”

“We” meant that Anne was doing this on her own.

“Sure I’ll do it. Nothing changed from Jim’s report yesterday, right?”

“You’re a saint, Sam.”

I picked up the phone and dialed the Up to the Minute Answering Service. Gracie was on duty. Behind her I could hear half a dozen other girls at switchboards.

“Doll,” I said, “I’ll be out for most of the afternoon. Anyone wants me, I’ll be back after six.”

Under her operator voice, Gracie talks Brooklyn like the Queen speaks English. “Be careful, you,” she said. She gets her ideas of private detectives from paperback novels.

We’ve never met. Going down in the elevator, I thought of Gracie as being maybe in her midthirties—which seems young to me now. I imagined her as blond and nicely rounded, sitting at the switchboard in a revealing silk robe.

I imagined the other Up to the Minute ladies sitting around similarly dressed. This is the privilege of a divorced and decorated veteran who once got kissed by a French field marshal.

My office is on the fifth floor. With a couple of errands to do, I crossed the vestibule and stepped outside. They tore down the elevated line before World War II, but better than a decade later, Sixth Avenue still looked naked in the October afternoon sunlight.

Across the way, the women’s prison stood like a black tower as all around it, paddy wagons unloaded their cargo. Some parents find out their daughters have run off to Fairyland. Others discover them at the Women’s House of Detention.

They use the old Jefferson Market courthouse next door to the prison as the police academy now. Sergeant Danny Hogan was showing a couple of dozen cadets in their gray-and-green uniforms how to write out parking tickets. Hogan and I did foot patrol in the old Fourteenth Precinct back when we were both starting out. He spotted me and rolled his tired eyes.

As I headed towards the subway, I saw the headlines and front pages of the afternoon papers. My old pal MacArthur had landed at Inchon a couple of weeks before. Maps of the Korean Peninsula showed black arrows pointing in all directions.

On the subway stairs, I felt something like the opposite of forgetting. A stray sprite with nothing better to do had tried to probe me. The mental image of Bertrade appeared and whatever it was immediately broke contact. I continued down the stairs, stuck a dime in the slot, and got on the uptown A train.

Early in life I heard about fairies. My mother’s mother saw leprechauns in the coal cellar and elves under the bed. Mostly I ignored her once I turned into a hard guy at the age of eight.

My mother was born and raised in the Irish stretch of Greenwich Village. She learned stenography, got a job in an import-export office, and married late. Sam Grant Senior was part Irish and not very Catholic. He had been on the road as a salesman for many years before my mother forced him to settle down. I was the only kid.

I remember my old man a little sloshed one night, telling me about having been on the night train to Cincinnati with “the crack women’s-apparel salesman on that route.” This guy was very smashed and told the old man how he’d gone down the path to Fairyland when he was young, stayed there for a few years, learned a few tricks. My father told me, “He said some of the ones there could read your mind like a book.”

I heard about the Kingdom beneath the Hill a few more times over the years. As a legend, it was slightly more believable than Santa Claus and a bit less likely than the fabled speakeasy that only served imported booze.

Then almost ten years ago, an elf almost killed me, and a couple of fairies saved my life. One of them was Bertrade.

The two errands I had were within a few blocks of each other. I rode the A train up to Penn Station and used the exit on Thirty-Third and Eighth. First I went to the General Post Office. The place is like a mail cathedral. I climbed the wide stairs, and my knee complained.

Inside under the high vaulted ceilings were big posters commemorating the pilots who had died flying mail planes thirty years back. I walked past the window that said Overseas Mail to the small window that said nothing.

It was there that I always mailed my letters to the Kingdom. The man on duty had a slight crease on the left side of his head—a veteran of something, I thought. I’d spoken to him a couple of times, asked him questions, and never got more than a shrug or a shake or nod of the head.

He took the letter. Right then, another mind touched mine, saw the image of Bertrade that I flashed, and bounced away.

The clerk’s eyes widened. He’d caught some of it, too. I took back the letter, picked up a pen, and wrote, “Urgent—contact!” on the envelope. The clerk nodded, stuck on a stamp I’d never seen before—one with a falcon in flight on it—turned, and put it down a slot behind him.

“They’ll have it by midnight,” he said in an accent I couldn’t catch. “Keep your head down. Tall elves are questing today.” Then he stepped away from the window.

I waited for a minute for him to come back. When he didn’t, I turned and walked the length of the two-block-long lobby all the way to Thirty-First Street. Maybe it was just an elf, lost and a stranger in the big city, who kept trying to bust into my head, and I was overreacting. Maybe I was lonely and wanted to see Bertrade.

Going down the stairs was tougher on my knee than going up them. I walked two blocks south on my errand for Jim and Anne. Thinking it was good to have a simple assignment to occupy my mind, I bought a late edition of the Journal American. It was four thirty-five. Some people were already heading for the subway.

Just west of Sixth Avenue on the south side of Thirtieth Street stood the Van Neiman, a nondescript office building. Across the street was a luncheonette. The only other customer was hunched over his paper; the counterman and waitress were cleaning up.

I ordered coffee, which was old and tired at this time of day, and sat where I could await the appearance of Avery J. Culpepper, CPA. His wife, Sarah, a jealous lady out in Queens, was convinced that he was stepping out on her.

Private investigators in one-man offices, like Jim Toomey and me, need to form alliances with other guys in similar circumstances. For the two of us it went beyond that. In France I was the one who got to smell the mustard gas, take out the machine-gun nest, and get my leg chewed up. For me, the real war lasted about two weeks. I got decorated and never fired another shot for Uncle Sam.

Jimmy passed unharmed right up through Armistice Day, won few medals, got to see every horror there was to see. I was hard to deal with when I got back, and my marriage to the girl I’d left behind only lasted as long as it did because she was very Catholic.

But Jim still woke up at night screaming. It drove Anne crazy and it broke her heart, but she stuck with him. For a while things got better. Lately they seemed to have gotten worse.

I thought about that as Avery J. Culpepper, wearing a light-gray suit and a dark felt hat, carrying a briefcase, and looking just like the photos his wife had supplied, came through the revolving door of the Van Neiman Building. A punctual guy, Mr. Culpepper, in his late thirties and in better shape than your average philanderer.

This was the first time I’d tailed him. Twice before Jim Toomey had followed Culpepper and ended up riding the crowded F train all the way out to Forest Hills. When Jimmy talked to me about it on the phone, even that routine assignment had him ready to jump out of his skin.

The time with me was a little different. Mr. C. came out the door and headed west along Thirtieth Street. I followed him for a few blocks through the rush-hour crowds pouring out of offices and garment factories.

He turned south on Ninth Avenue then turned west again on Twenty-Ninth. These blocks had warehouses and garages, body shops, but also some rundown apartment houses. Here, the crowds heading east for the subways were longshoremen, workers from the import-export warehouses. I stayed on the other side of the street, kept an eye on him, and watched the sky, which was getting dark and cloudy.

Culpepper crossed Tenth Avenue. A long freight train rolled over the elevated bridge halfway down the block. On the north corner of the avenue was an apartment house that must once have been a bit ritzy when this was mostly residential but now looked rundown and out of place. That’s where he turned and went in.

I glanced over as I passed to make sure he wasn’t lingering in the entryway, waiting to pop out and give me the slip. As I did, a light went on, up on the third floor. I noted it and wondered if that’s where he was. Then I continued walking till I was under the train tracks. Already the streets and sidewalks were getting empty.

At the end of the next block, beyond Twelfth Avenue, was a pier with a tired-looking freighter moored, and beyond that, the river. A string of barges, each with its little captain’s shack, went by pulled by a tug.

It was growing dark and all the warmth had been in the sun. I paused and turned like I’d forgotten something. Culpepper had not come out of the apartment house.

I crossed the street then walked back to the building he’d gone in. I spotted no one watching me. The outer door was open. One side of the entry hall was lined with mailboxes, twenty-four of them. I took out my notebook and copied the names. Many times when the husband strays it’s with someone the wife already knows.

The third floor was where I’d seen a light go on. So I gave those mailboxes my special attention. Number fifteen in particular had a recently installed nameplate. Mimi White, it read. If that’s where Culpepper was, the name seemed too good to be true.

Somebody upstairs had the news on the radio. In the first floor back, the record of “If I Knew You Were Coming, I’d Have Baked a Cake” got played a few times.

As I finished copying the names, an old lady came in carrying an armload of groceries. Like the building itself, she looked like she’d seen better days. I held the door for her, said my name was Tracy, that I was from the National Insurance Company and was looking for a Mr. Jameson, who was listed as living at this address in apartment number fifteen.

She thought for a moment, then said number fifteen had been occupied for years by an Asian couple. They had moved out, and it had stayed empty for a while. A young lady had moved in just recently. I thanked her and noted that.

As she headed upstairs, I heard footsteps and voices coming down. I went outside, crossed the street, turned, and walked slowly back towards Tenth Avenue. I noticed the third-floor light was off.

When I paused on the corner, I saw the couple. Mr. Culpepper had left his briefcase upstairs. The lady he was with wore a short camel-hair coat, a nice black hat set on her blond hair, and high heels. She looked like her name could easily be Mimi and like you could take her places.

Culpepper glanced neither left nor right as they walked to the corner and he hailed a cab. In my experience, a guy stepping out with a good-looking woman usually wants to see who else notices. Culpepper apparently was made of sterner stuff.

Walking back across town, I was amazed at how easy this assignment was and wondered why that bothered me. I’d detected no presence of the Gentry in the last couple of hours. That probably meant the one or ones I’d felt earlier had found whoever they were looking for.

Or maybe they had discovered I was right where I was supposed to be and doing what they wanted me to. Being involved with the Fair Folk had always left me feeling like a dollar chip in a very big game.

I remembered a face, elongated and a little blurred, that I’d once seen. It was a tall elf with a smile that said, “How stupid these mortals are.”

On the A train downtown, I got a seat and thought over that first time I felt an alien presence and how close I came to dying from it.

In ’41 I did undercover work, none of it strictly official. My old regiment was the Sixty-Ninth, “The Fighting Irish,” and our colonel was Donovan—the one they called “Wild Bill.” Later he was the guy who started the OSS and became the US intelligence chief in World War II. But even before that war, he had connections in Washington and an interest in foreign espionage in New York City. He got to do something about it.