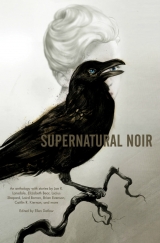

Текст книги "Supernatural Noir "

Автор книги: Paul Tremblay

Соавторы: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan,Brian Evenson,Joe R. Lansdale,Lucius Shepard,Laird Barron,Nate Southard,Gregory Frost,John Langan,Richard Bowes,Tom Piccirilli

Жанры:

Городское фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Genius. Something perked up in his fried brain. “What’s your name, sweetheart?”

Sweetly she lisped, “Little Shit.”

He gave a surprised laugh, then got threatening. “Cut the crap. What’s your real name?” Perps thought they had power over a little kid once they had your name.

Like she’d tell him. Like she even knew. “That is my real name, mister, honest. Little Shit.”

“I ain’t callin’ you that.”

“You can call me whatever you want to, mister.” How about Trouble? Ball-Buster? Bait?

He gave the swing a hard shove that pretended—not very well—to be playful. “Pretty little thing like you,” he rasped. “Somebody might take advantage.”

She shrieked and fell against him at an angle that would keep him from having contact with the dead giveaway of her boobs. He went for her crotch. These scum were so predictable. If he got his hand inside her pants it’d out her as an adult, but she wouldn’t let that happen. Barbie and some of the other hos on her advisory committee wore baby-doll dresses with no panties, but besides the chill and the strategic issues—social workers couldn’t talk without saying “issues”—she wasn’t about to let filthy fingers that had been who knew where come into actual contact with anything personal. She’d aced that Human Sexuality class.

She did have to get close enough for long enough that he’d do something incriminating, and so she could collect identifying information: his body-dirt-cigarettes-wine odor, a ridged scar on the inside of his left wrist, a smooth bald spot fringed by almost silky hair. Auditory info was easy—his voice, the way he breathed. Easiest to gather but hardest to convince anybody by was the thought pattern, in this case a jumbled buzz with stretches of spooky purplish clarity. You couldn’t put it in a report or say it on a witness stand. A lot of the most true stuff in life you had to be careful about admitting to.

When she faked losing her grip on the swing chains, he caught her, thinking something like, “All right!” and tried again to stick his hand between her legs. Clamping her thighs to trap his forearm in the act, she pressed the button on her bra strap.

The cops materialized, only two this time, and bored, distracted, Raul wishing he was home with his new baby, Dixie with a migraine coming on. It was better when there were a lot of them and they were into it and they invited her out partying afterward and bartenders who’d checked ID a million times carded her again, and people made rude cracks about her size and she made rude cracks about theirs, and it was all good. Tonight was just business.

This would-be perp was squealing about castrating bitches as Little Shit collected her fee from Raul. His “good job, kid” was like you’d talk to a two-year-old who’d gone potty in the toilet, but Little Shit decided to take it as camaraderie and reciprocated by putting in his mind the sweet, powdery smell of his baby’s head. Best she could do right now. Might help, might make things worse. You had to take risks. Not for the first time she wondered if people could sense her messing around in there. On her way out of the park, she fixed Dixie’s headache, not because they were homies or anything, just because she could.

Little Shit wasn’t what they knew her by at school. She’d made that name up, too, for her A and A+ papers and exams and her GREs that would get her into grad school. Also what Lourdes called her, off the “Pretty Names” list she kept for when there was a possible new friend or lover. She was a self-made woman, every time, and proud of it, never mind what she was learning about how most people’s identity and sense of self were formed. She’d never been most people. Might as well make something of that.

And she’d made quite a bit of it, actually, in her almost twenty-three years. She kept working on self-improvement, but overall she was down with how her life was going. Even before she got her degree she was making more of a diff than most people did in their whole entire lives.

Sometimes she felt sorry for the perps, though. Pitiful dudes, once in a while chicks, a lot of them looking for what they called love. Some people would call just about anything love. Others didn’t have “love” at all, even in what they believed was private vocabulary. She herself had no clue what love was, but most of the time it was fun trying to figure it out.

Like spring break with Lourdes. When they’d walked on the beach holding hands people’d probably thought they were mother and daughter. Like every other social worker, Lourdes talked a lot about “boundaries,” so holding hands was just about all they did in public. It’d be funny if somebody saw them doing other stuff and called the cops on Lourdes, but Lourdes didn’t see the humor. Lourdes didn’t see humor in much of anything, and she wouldn’t find it amusing or noble if she knew how Little Shit was putting her personal strengths to use working her way through school.

It was a syndrome, what fools called a birth defect. Fools like her egg and sperm donors. They could have at least put something on her birth certificate other than “Baby Girl.” Their loss. No way did the word “defect” have anything to do with her.

If she’d ever known the name of the syndrome, she didn’t now. Some people with it were normal height, but she was short enough to be almost but not quite an official “Little Person,” a cutesy label with not nearly the coolness of “Little Shit.” Tendency toward hip dysplasia. Crooked little fingers and toes that worked fine and curled like macaroni in lovers’ mouths, in Lourdes’s mouth. Streaked hair auburn and strawberry blond and almost black, which she used to dye all one color but now she made sure to brush it so all the colors showed, gleamed. Lourdes had a thing for long hair. She also had a thing for fuzzy shaved heads—actually, for fuzzy shaved anythings.

The ability to screw with other people’s thoughts was probably part of the syndrome, too. Lourdes didn’t know about that, and it wouldn’t be in her records even if she had any. That probably wasn’t why she’d been thrown away, either, unless she’d been seriously precocious; when she used to try to figure it out, she’d usually decided it was because of her weird little fingers and short legs.

In the days after the perp on the swing, she and Lourdes had one of their big dramatic fights and big dramatic reconciliations. Both would’ve been easier if she’d poked around to find out what Lourdes secretly wanted from her, but that would be cheating.

When she got an A– on her policy paper, though, she did a quick intervention. First she shifted a few things around in the teacher’s pathetic OCD mind, and let that sit for a day or two. Then she challenged the six lost points, and the teacher couldn’t quite remember why he’d deducted them. It was really sort of embarrassing to watch, so she conceded two points and the plus, but she won back four, which made it the A she deserved.

When Raul texted her JOB 4 U, she was working with her group on the case presentation and then they went for tamales and beers. She texted back LTR but it was almost nine before she could call him. “What up?”

“Where the hell you been?” The sound of the baby crying receded and she heard a door shut.

“Um? Studying?” She’d give him that much.

“Um? This is your job?”

“My bad.”

He wasn’t letting it go. “You don’t take six fucking hours to get back to me.”

“Hey,” she said, “dude. You could always find somebody else.” They both knew how valuable and rare her particular skill set was, and there were other cops and lawyers and PIs in this town who might have an interest in what she could do. Also that she needed the money and she loved the job.

For somebody in such a hurry he didn’t seem to mind wasting more time. During the pause she did dishes, banging as much as possible without breaking something.

Raul finally got over himself enough to tell her, “Looks like we got us a social-worker perp.” She could hear his smirk.

“You’re smokin’ crack!”

“Not today.”

He always said that when she said that. This time she didn’t laugh. “I meant, ‘really’?”

“Yeah, really. Hits on underage males and females she’s doing therapy on.”

“What do you mean, hits on?”

His voice got weird—husky, a little breathless, raggedy. She felt a stirring in her own groin. Normal, she knew; occupational hazard. Still, it bothered her, made her vigilant about her own motivations. She hoped Raul was watching his. “Gropes minors,” he explained. “Tells them bullshit like it’s part of the treatment so they’ll ‘learn to trust.’ ”

“This one’s mine.” In her minuscule kitchen space, balancing a plate in both hands to keep from dropping it, she held her breath and focused her mind.

“Thought you might say that.”

“Fer shizzle.”

“Come again?”

“Oh, sorry, old dude. Yeah, sure, you’re right.”

“Any reason you can’t speak English?”

“Gotta be hip, Raul, my man. Gotta be cool.”

“High on my list.”

“Who’s the slimeball? Hopefully nobody I know.”

“Name’s Lords something.”

She went very still and repeated it the way he’d said it. “Lords?”

Audibly shuffling papers, he spelled it. “Lourdes Malone. You know her?”

“No,” she said.

She made lists and flow charts and went through the steps in the social-work problem-solving process up to “implementation.” She did not think about Lourdes’s hands, Lourdes’s laugh, Lourdes’s tongue.

The first thing she had to do was pick a fight and stage another breakup. That wouldn’t take much. The hard part was that if Lourdes was doing this stuff, they’d never make up.

Having to take a semester off school would have sucked even worse, so she was totally relieved to find out about the online option for three of her four classes. Good thing they didn’t use video, or even audio, because if she could get her voice to change enough she’d have to keep it that way until this was done. She recorded herself using higher and lower pitches, various bogus accents, a lisp, a horror-movie whisper. The cartoon squeak would be the easiest to keep going but it was also the most obviously fake. Finally she found a website with audios of voices and accents, played around with the kids’ ones until she came up with one that sounded kind of real and that she could manage, talked aloud to herself in it for days, and was happy when Raul called and thought he had a wrong number and she had to say code before he was convinced it was her. He was both pissed and impressed. Cool beans.

She dug out the rose cologne and the ginger lip gloss. In real life she didn’t love all that girlie stuff, on principle, but the job gave her an excuse and it was kind of cool, like Halloween, like a kid playing dress up.

Next was the hair. Without looking in a mirror she whacked it off—scraggly would be in character—and then dyed it what the box called “Mahogany Brown” but came out Carrot-Top Red. She told her reflection, “You are uuuuuugly, girlfriend, you know that?” She looked so different that she tried messing with her own mind, and couldn’t really tell if it worked or not, if she even got in. Could there be such a thing as autotelepathy? Probably—so far in her life she hadn’t run into very many totally impossible things.

Voice, hair, posture, gait, tics, breathing patterns, gestures—by now she knew how to do all that. A few hours’ practice to get them down, a little more time and effort when this was over to get rid of whatever she decided not to keep as part of her ever-evolving self.

Okay, all five of the regular senses were covered: she looked, sounded, felt, tasted, smelled different. But this was not exactly regular. This was Lourdes.

What would happen if Lourdes recognized her? There’d been some rough stuff, all in play, definitely consensual. But if Lourdes was really a pedophile, or if she wasn’t and she went off about being set up, what would happen? It seriously bit that this reading and screwing around with thoughts thing didn’t work worth crap from a distance.

For a day and a night she considered how much she was willing and able to do. A lot, it turned out. In a weird way she owed it to Lourdes not to hold anything back, not to underestimate either of them.

But there wasn’t enough time to lose or gain more than a couple of pounds or get Botox in her lips or get the very cool snake tat removed—after all the money and pain it had cost her she’d have hated to lose it, and Sammy’s artistic integrity would have been offended, but she’d have done it if she could. Hopefully things wouldn’t go far enough for Lourdes to find it.

Marina Abramovic, mutilating herself for art on YouTube, was one out-there chick, but fresh wounds would be suspicious. Same problem with actual surgery. She had to settle, uneasily, for blue contacts, lashes thickened and curled, a yellowy tan from hours under a lamp, a vaguely spider-shaped birthmark colored on the inside of her thigh, shaving all body hair and shaving it again for maximum smoothness, and wrestling her boobs into submission with an Ace bandage wrapped tight as a girdle. That last one was a big risk; Raul and his team better get right in there if kid nipples were what floated Lourdes’s boat.

When she showed up at the DA’s office in a lavender baby-doll dress and, just to stay in character, no underwear, Raul had no idea who she was. Even though that’s what she was after, it kind of hurt her feelings, which was weird.

To the giraffelike assistant DA at the desk, she introduced herself as Madison Smith, the preppy name she and Raul had finally compromised on. Behind her she heard Raul come up out of his chair. She probably could have just stirred up his thoughts so he’d believe her, but it was more fun to watch him do it himself. “Shit,” he said.

“Yup,” she said in the voice.

“Fuck.”

“Nope.”

“How’d you do it?”

“Trade secrets.”

“You’re taller.”

“That’s just shoes, dummy.” She showed him, careful not to lift her foot too high and expose herself.

His hand went briefly to her shoulder. Like every other time they’d touched—accidentally in passing, comradely fist bumps, brush of the hands maybe or maybe not flirtatious—she stiffened. Then he nodded. “It is you.”

“Whatever that means.”

“I take it,” Giraffe said dryly, “we’ve established that the disguise is convincing. Can we move on?” First, though, Giraffe had to brag about other child sex-abuse cases she’d prosecuted. “Sixty-nine years to life is what I got,” she told them about one particularly nasty one. The passionate, joyous pride in her voice and in her heart was really pretty creepy.

“Very good,” said Raul. Little Shit was getting a contact high from all this moral certainty.

“I’m telling you, section 85.67 of the penal code is a wonderful tool. No judicial discretion to get in the way of justice. When I know in my gut, as a person, that somebody should get life, I pick the charges and I make it happen.”

“Enhancements,” Raul said to Little-Shit-as-Madison. “Gotta get those enhancements.”

“Enhance like what?”

“GBI’s always good.”

“Great bodily injury,” Giraffe supplied, and she and Raul laughed.

“Double my rate.”

“Mayhem works, too,” Raul allowed. “That’s just disfigurement. You already got some of that goin’ on. What’s a little more disfigurement for the cause?” She flipped him off.

“And/or torture,” added Giraffe.

On a roll now, they listed burglary during the crime, which wasn’t likely in this case, and multiple victims, which was. Felony priors would have been even better. Administering controlled substances during the crime had a certain appeal; Little Shit kept what she knew about Lourdes’s sources to herself. And there was kidnapping, which could just mean driving to more than one location or even moving from one room to another. Kidnapping was good.

“Whatever works,” she told them.

“You’re awesome.” Giraffe was doing something on her computer—researching, entering data—and she said it with no meaning, like you’d say, “Have a nice day.”

“I’m sayin’,” said Raul, meaning it.

“Innocent till proven guilty, though, right?”

Giraffe waved one long hand. “Right. Sure. Of course.”

“You going all social worky on me?”

She rolled her enhanced eyes at him, then moved to where she could see the computer screen. Giraffe was playing Scrabble and had just typed in a seven-letter word Little Shit had never heard of.

During the two and a half days it took to figure out the plan and get everything ready, she wouldn’t let herself obsess about the kids who might be getting hurt. She was in Raul’s office when he called Lourdes posing as a caseworker in a homeless shelter where somebody would confirm they had a staff person by the fake name he gave if she checked. He was able to make an appointment the very next morning for his consumer, Madison Smith. Little Shit grinned at his use of the PC word.

Lourdes called her a couple of times and then when she didn’t answer texted HOW R U? She texted back K, then ignored the MUSM although she did miss her, too.

Just for grins, she hauled out the book she’d paid a fortune for, for the class she now couldn’t take this semester, and poked around in it for a diagnosis for somebody who finally decided they loved the person they’d been with for almost a year only after they were part of an elaborate scheme to find out if that person was a serial sex offender. Depersonalization disorder and Dissociative Fugue and Sexual Deviance had possibilities. So did Reactive Attachment Disorder. “Attachment” was on the syllabus of one of the classes she’d be taking online. So much to learn, so little time.

The contacts were bothering her eyes, the boobie girdle was pinching and itching in addition to aching, and there was a burn blister on her shoulder from the tanning lamp. Eye drops, non-allergenic gauze and tape, and Solarcaine went onto her expense report with receipts attached along with the ones from the thrift stores, where she’d loaded up with outfits for a lot more days than this thing better take, including glittery capris like she’d been hunting for and a pair of purple Crocs that looked brand new, plus a ridiculous white jumper with a pleated skirt that would get recycled right back to a thrift store when this was over. There was a really short blue satin skirt she’d have looked stellar in, but Madison Smith was supposed to be eight years old. Being professional sucked.

When Raul-as-caseworker came to pick her up he had that intensely calm, focused-mind thing going on, like a gleaming tube. There was nothing in there about his baby or his wife or the Cornhuskers or the head cold coming on. Madison Smith was in there, and Lourdes Malone, and taking this thing step by step by step and bringing it on home.

He stared at her, circled her, felt her hair, told her to walk around, sniffed, told her to say something. If he’d tried to taste her, she’d have had to hurt him. It was messed up how proud she was when he pronounced, “Madison Smith.” Pride and happiness and all that crap could get in the way of doing what had to be done just like sorrow and rage could.

Madison Smith wasn’t glad to see Lourdes, hadn’t missed her, didn’t want to run into her arms. Madison Smith also didn’t want to put her behind bars for sixty-nine years to life. Madison Smith wasn’t real, but Little-Shit-as-Madison was, and she picked the chair in the dimmest corner of the dim therapy room. She’d been thinking Madison would be surly and smart-ass, like she herself had been when they tried to make her go to therapy, but now it occurred to her that if Lourdes had to win Madison over it would drag this thing out, so she went and got a baby doll from the toy box in the other room and curled up with it. This time finding tears wasn’t hard.

Raul-as-caseworker was so hip-casual when he introduced Madison Smith and Lourdes Malone that neither one of them could stand him, and the way he went through why Madison was here—sexual assault top on the list, naturally—made her feel dissed and dirty. But when he promised he’d be right outside in the waiting room she was relieved, and when he left the room she was actually kind of scared.

Lourdes had been watching her even when she hadn’t looked like she was. Now she asked if she wanted a Coke. Little Shit drank Pepsi. Madison said sure and thank you and held the can in both hands with the baby doll in her lap. Queasy from all this vulnerability, she vowed to jack something out of here today, one of the smaller toys supposed to get kids to drop their guard, the Mardi Gras beads maybe. If Lourdes turned out to be innocent, she could have them back. If not, plenty of kids on the street would like something cheap and pretty.

Lourdes settled back. Today her hair was a good color for her, yellow silk in the lamplight, and it would be nice to touch. Her hands were crossed in her lap, crisp white cuffs folded back. Little-Shit-as-Madison crossed her own fidgety hands the same way and tried to keep them still.

She’d never seen Lourdes professional like this, majorly conscious of herself and of her client. Being on the receiving end of all that was creepy and flattering and creepy because it was flattering. You didn’t have to have a syndrome to pick up on it.

“I’d like to tell you a bit about myself so you know who you’re dealing with.”

About half of what Lourdes told Madison, Little Shit was pretty sketched about because she’d never heard it before. Looking in her head to see what was true would pull her out of character, and it didn’t matter anyway.

When Lourdes asked if she had any questions, she didn’t. “Are you a checkers player, Madison?”

This must be in the Play Therapy class she hadn’t taken yet. She had Madison say, “Am I a what player?”

Lourdes showed her the checkerboard set up on a table, neat red and black squares, red and black discs like Pogs from when she was a kid. “Have you ever played?”

“Games are retarded.” Now that she got how insulting that was to the people you used as an insult, like “gyp” and “You run like a girl,” she didn’t like saying it, but Madison did.

“Sometimes it’s easier to talk when you’re doing something else besides just sitting and talking. I could teach you the basic rules.” This wasn’t working. Lourdes ought to give it up.

“I didn’t come here to play stupid games.”

Lourdes took the gift. “Why did you come here, Madison?”

“Because the judge said I had to or go to juvie,” she sneered.

“Why did the judge say that?”

“Because I’m a bad kid?” Hopefully that wasn’t overplaying it. Madison lifted her feet up on the chair and hugged her knees and buried her face, with the doll squished in the V between her thighs and stomach. This was pretty uncomfortable but it hid a lot of her and showed a lot else of her.

“You’re not a bad kid, Madison.” That was definitely in the therapist rule book. Little Shit wanted to roll her eyes and groan at how predictable it was, and Madison wanted to go sit in the nice lady’s lap.

“I do bad things.”

Lourdes didn’t say anything. That was use of silence to get the client uncomfortable enough to fill it. Little-Shit-as-Madison didn’t say anything, either.

Madison’s thoughts were babyish, full of holes and sharp broken pieces and mushy spots, mostly about fighting things off—fighting something off right now, something circling and poking and trying to get in—and about wanting somebody to love her and fighting off anything that looked like love and letting in stuff that wasn’t even close, not knowing the difference between love and danger. If there even was a difference. Little Shit knew this space.

Eventually Lourdes was the one who broke the silence and said a few more gentle, encouraging things. Little-Shit-as-Madison just sat there all curled up until her back started to hurt and she couldn’t stand the boobie girdle cutting into her anymore, and then she threw the doll on the floor and got up and left. The Mardi Gras beads in her pocket didn’t rattle or bulge.

Raul-as-caseworker was texting and she walked right past him and out the door of the office and she found the stairway and ran down three flights and was in the street before he caught up with her. “You got a problem with elevators? Jesus.”

When she got home she stripped, soaked in a bubble bath, listened to a Grizzly Bears CD really loud, put on clean pajamas. To sop up some of the longing to go out dancing with Lourdes, she read as many pages as she could stand in the social-work policy book.

The next day she went by herself. Whether Lourdes thought that made Madison more alone and vulnerable or not, Little Shit did. This time she sat on the couch so there’d be a space beside her. Pretty much the same thing went down. After a few minutes and a few words, Lourdes stopped talking.

Madison was antsy and went ahead and filled the silence but not too much, too soon. “I’m gonna be a social worker,” she said in the squeaky voice that would have been fake even if Madison had been real. “I’m gonna help kids.”

“Do you know a lot of kids who need help?”

“Well, yeah-uh.”

“Why do they need help?”

Don’t make this too easy, Little Shit warned Madison Smith. Let her think she’s God’s gift to screwed-up kids. “All kinds of stuff.”

“Like what?”

“My friend Kelsey? Her mom’s a crack ho.” Madison watched Lourdes to see if she was shocked. Little Shit knew she wouldn’t be.

“That’s hard.”

“And there’s this dude at the center? Doesn’t know if he’s gay or straight or bi or whatever. He says he’s queer.” She giggled. She had a whole list of sex-related issues to warm Lourdes up with.

“What do you need help with, Madison?”

Too fast, you idiot. I don’t trust you yet.

Madison cradled the baby doll against her almost-boobless chest and cooed to it, “It’s okay, little girl, I won’t hurt you, you’re safe with me.”

Lourdes took the hint. “It’s hard to find a safe place, isn’t it?”

Madison nodded. Little Shit let Madison nod.

Now Lourdes came to sit beside her on the couch. Madison wanted to run out of there and to snuggle. Little Shit wanted Lourdes to make a move. Make a move, come on, let’s get this over with.

Lourdes tucked one leg up under her, wedged herself against the pillows, leaned her elbow on the back of the couch, and propped her head on her fist. There was one of those silences. Madison got weirded out and threw the doll down and knocked the checkerboard off the table and left.

On her way out, Little Shit thought she’d just jump in and jump out of Lourdes’s head, not to change anything, not to give her the idea of assaulting young kids if it wasn’t already in there and not to take it away if it was, just to see what the hell was going on. She couldn’t get in at all. That had never happened before. Madison Smith might not be real, but she was really in the way.

This went on for over a week. The online classes started and she already had two papers. She had to keep shaving, and her crotch prickled and itched. Her boobs, shoulders, neck, back hurt all the time even when she unwrapped herself at home—she was going to need a serious massage when this was over, which would go right on her expense report. She wasn’t sleeping very much.

It turned out that the Madison Smith story had to spin out past where they’d planned it, and now she was making it up as she went, getting the poor kid more and more messed up, hoping she could keep it straight or if she got caught in a lie it would look like Madison’s pathology. Like a bug under a magnifying glass, she was about to burn to a crisp any second under Lourdes’s attention. And there was not a single sexual vibe.

“I think she’s innocent.”

“Nah.”

“What if she’s innocent?”

Raul was thinking. She was too tired and stressed out to see about what. She almost fell asleep. Finally he swiveled, tapped on his keyboard, sat back in his chair, leaned forward again to turn up the volume.

Voices of prepubescent girls and boys came up, seven or eight different ones, some of them hard to understand, some clear and close. Soft-spoken male and female interviewers asked carefully nonleading questions, just like in the role-play in Forensic Interviewing. At least one of the kids was crying. Another one kept making a barking sound like a goofy cartoon seal that was probably laughter. One of the interviewers had a cough.

Raul closed the audio file, peered into the coffee mug on his desk that had DADDY on it in puffy blue letters, sighed and got to his feet. “Coffee?”

She’d told him a million times that she took her caffeine cold. She said, “Uh. No.”

He missed the sarcasm or ignored it, which pissed her off more. She thought she might just get outta here while he was refilling his stupid mug, but she couldn’t quite.

When he came back she said, “Nothing was really disclosed on there.”

“Makes you wonder, though, all that disgusting stuff.”

“That wasn’t at the level of an outcry.” Using the intense word “outcry” in such a familiar way made her feel like a real social worker.

Raul patted her shoulder. “That’s why we got you.”

“Probable cause,” she said, like she knew what she was talking about.

“Something like that. So, you okay now?”

For a split second she thought he was asking if she felt okay, if she was upset, if she was sick. But he just meant was she okay to keep going with the job. She said, “I guess,” and that seemed to be enough for him. Whether it was enough for her they’d just have to see.

By about two thirty in the morning she really, really wanted to smoke a joint to help her sleep, but that would compromise her testimony if for some reason she had to pee in a cup in the next few hours. She did drink part of a beer and almost hurled.

The next morning, Little Shit had Madison sit in the chair where her feet didn’t quite touch the floor. Lourdes settled herself on the closest end of the couch. “How are you today?”

“You look terrible.”

“I didn’t sleep very well last night, but I’m fine. Thank you for noticing, Madison. That’s very nice of you.”

“You going to fall asleep?”

“No. I promise.”

“You going to die?”

“Oh, honey, don’t worry. I’m right here with you.” Lourdes reached over to pat her knee but got her thigh instead, the inside of her thigh.

“Oops,” Lourdes said softly. “Sorry.”