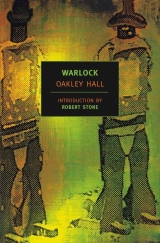

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 34 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

MORGAN stood at the open window with his tongue mourning after a lost tooth and the night wind blowing cool on his bruised face. The night was a soft, purplish black, like the back of an old fireplace, the stars like jewels embedded in the soot. He stood tensely waiting until he saw the dark figure outlined against the dust of the street, crossing toward the hotel. Then he cursed and flung his aching body down into the chair, and took out a cigar. His hand shook with the match and he felt his face twisting with a kind of rhythmic tic as he listened to the footsteps coming up the stairs, coming along the hall. Knuckles cracked against the panel of his door. “Morg.”

He waited until Clay rapped again. Then he said, “Come on in.”

Clay entered, taking off his hat and bowing his head as he passed through the doorway. There was a strip of court plaster on his cheek, and his face was knuckle-marked enough. Morgan looked straight into his eyes and said, “You damned fool!”

“What was I supposed to do?” Clay said, closing the door behind him. “Post you out because you were going anyhow?”

The blue, violent stare pierced him, and his own eyes were forced down before it. “Why not?”

“Would you kill two men to serve a trick like that, Morg?”

“Why not?” he said again. His tongue probed and poked at the torn, pulpy socket. “One,” he said. “I had to take scarface first and Lew crawled for it.” With an effort he looked back to meet the blue gaze. “I told you I couldn’t let a man get away with burning me out!”

“I asked you to leave that alone.”

“Post me then, damn you!”

Clay moved over to sit on the edge of the bed, with his shoulders slumped and his face sagging in spare, flat planes. He shook his head. “I couldn’t anyhow. I am not marshall any more.”

“Well, I will back a play I have made. I don’t go unless you post me.”

Clay shrugged.

“What would it cost you? It might win you something.”

“No.”

“What does Miss Jessie Marlow say?”

Clay frowned a little. He said in a level voice, “What would you try to do this for, Morg?”

Because I never liked to look a fool, he thought. He had never hated it so much as he did now. “God damn it, Clay! A whole town full of clodhopping idiots aching for you to play the plaster hero for them one time again, and post out the Black Rattlesnake of Warlock. Which is me. And why not? It would have pleased every damned person I know of here except maybe you. Maybe you are yellow, though – a damned hollow, yellow Yankee. I hate to see you show it for these here!”

“They can have it that way if they want it. I have quit.”

“You could have posted me and quit after the big pot when I’d run.”

“It wasn’t a game to cheat and make a fraud of,” Clay said. His face looked pasty pale beneath the bruises. He shrugged again, tiredly. “Or maybe it was and it took a thing like this to show me. And maybe if it could be that, it is time and past time to quit.”

“Clay, listen. I am sick to death of this town! I am sick of sitting in the Lucky Dollar taking Lew’s money away, I am dead sick of watching the gawps from the chair on the veranda. I want to get out of here! It was a good reason for me to get out of here. I am trying to tell you it would have pleased everybody, me included. Now you are a damned has-been and a fool besides.” And you have not quit, he added, to himself; now you have not, whatever you think.

“Why, I have pleased myself then,” Clay said. He said, quietly, “What are you so mad about, Morg?”

He sat slumped down in his chair with his cold cigar clenched between his teeth. For whom was he doing this, after all? To please himself, was it? At least he wanted a live plaster saint rather than a dead one, and for that he had done what he had done, and for that he would do more. For whom? he wondered. It stuck now to try to say it was for Clay.

“Mad?” he said. “Why, I am mad because I have looked a fool. I am mad because I am used to having my way. I will have my way this time. If you won’t post me for that, I will—” He stopped suddenly, and grinned, and said, “I will ask you for it for a favor.”

Clay looked at him as though he were crazy.

“For a favor, Clay,” he said.

Clay shook his head.

“Then I will see what it takes. Do you think I can’t make you do it?”

“Why would you?” Clay said.

“I said I will have my way!” He felt his fingers touch his cheek, and the tic convulsed his face again.

“I have quit,” Clay said. “I will post no man again, nor marshal again.” He held his hand up before his face and stared at it as though he had never seen it before. “What is all this worth?” he said, in a shaky voice. “What is all this foolish talk? What’s my posting you out of Warlock worth to anybody?”

“It is worth something to me,” he said, under his breath.

“What are you trying to make of me?” Clay went on. His voice thickened. “You too, Morg! Not a human being at all, but a damned unholy thing—and a fraud of a thing in the end. No, I have quit it!”

“Do it for me, Clay,” he said. “For a God-damned favor. Post me out and turn me loose. I am sick to death of it here. I am sick of you.”

He saw Clay close his eyes; Clay shook his head, almost imperceptibly. He continued to shake it like that for a long time. He said, “Go then. I don’t have to post you so you can go. I—”

“You have to post me!”

“As soon as I did you would walk the street against me.”

“I’ve told you I wasn’t a stupid boy to play stupid boys’ games!”

“I don’t know that many of them was stupid boys,” Clay said. “But every time now it is that way. If I posted you out for whatever reason you made me – no sooner it was done than you would come against me. No, God, no!” he groaned, and slapped his hand hard against his forehead. “No, no more! What have I done that I was made to shoot pieces off myself forever? No, I have done with it, Morg!”

“Clay—” he started. “Clay, what are you taking on like this for? All I am asking is post me and I will get out of town on the first stage or before it. Good Christ! Do you think I am fool enough to—”

“I will not!” Clay said. His lips were stretched tight over his teeth, and his face looked pitted, as though with some skin disease.

Morgan got up and stood with his back to him. He could not look at that face. He said, “If you had been any kind of marshal here you would have posted me before this. But I guess you couldn’t see the hand in front of your nose. That everybody else saw.”

“What?” Clay asked.

“You should have posted me for killing McQuown, for one. If you had been any kind of marshal.”

Clay said nothing, and he felt a dart of hope. “If you had been any kind of marshal,” he said again, “which was supposed to be your trade, but I guess you did not think so much of your trade as you liked to make out. And before that. Those cowboys that stopped the Bright’s City stage didn’t kill Pat Cletus.”

“I don’t believe that, Morg,” Clay said, almost inaudibly. Then he cleared his throat. “Why?”

Morgan swung around. “Because Kate was bringing him out here to show me she had another Cletus to bed her, as big and ugly as the first one. I am tired of watching that parade. Do you think I like her throwing every trick she has rutted with in my face?” His heart beat high and suffocating in his throat as Clay raised his head, and the blue stare was colder than he had ever seen it before. Then, almost in the same instant, it seemed to turn inward upon itself, and Clay only looked gray and old once more.

Do you have to have more? he cried, to himself. For maybe the curse upon him was that now even the truth itself would not be enough. He said calmly, “Why, then, if you will have more I will tell you why Bob Cletus came after you in Fort James.”

Clay’s head jerked up, and Morgan laughed out loud, proud that he could laugh.

“Are you listening, Clay?” he said. “For I will tell you a bedtime story. Do you know why he came after you? Because he wanted to marry Kate, the son of a bitch. And the bitch – she told him I might make trouble, and he had better see me. So he came to see me. You didn’t know you killed Cletus over Kate, did you?”

“Kate?” Clay said; his eyes had a pale, milky look.

“I told him it wasn’t me he had to worry about, it was you. You. For you had been rutting Kate and you were jealous by nature and no man to fool with. He was mad because she hadn’t told him about you, so I told him if he wanted Kate he had better get you before you got him, and sent word roundabout to you that he was out—”

His breath stopped in his throat as Clay got to his feet. But Clay only went to stand at the window. He leaned one hand upon the sash, staring out.

When Morgan spoke again his voice had gone hoarse. “By God, it was the best trick I ever pulled,” he said. “It made you a jackass and him a dead jackass – and Kate—” He stopped to catch his breath again. “Do you know what has always eaten on me? That nobody knew how I had served you all. It was a shame nobody knew. But how I laughed to think of Cletus jerking for that hogleg like it was a fence-post stuck in his belt. And you—”

Clay faced him. “He never did draw,” Clay said. “I don’t think he ever meant to. You are lying, Morg.” There was a little pink in his face and his expression was strangely gentle. “Why, Morg, are you trying to give me that, too? I don’t need that any more.” Then his eyes narrowed suddenly, and he said, “No, it is not even that, is it? You are telling me something to kill you for, not post you.”

“I told you I don’t play boys’ games!”

“Stop playing this one.”

“It is so, God damn you to hell!”

“Why, I expect part of it is,” Clay said. “I knew you had been in on it, for I have seen you chewing yourself. I expect you told him something like that to scare him so he would let Kate be. Not thinking he would come to me, though maybe you fixed it so that cowboy told me he’d heard Cletus was after me on account of Nicholson and I had better watch out – just in case Cletus did decide to make trouble. But I don’t believe he meant to draw on me; he just wanted to find out about Kate when he called after me. I was just edgy about any friends of Nicholson’s, was all, and thought he was out for blood.” He stopped, and his throat worked as he shook his head. “It is not so, Morg.”

Morgan stared back at him. Strangely it did not shake him that Clay had known, or guessed; he only felt dazed because he could not see what he could do next. He had chewed the end of his cigar to shreds, and with an uncertain movement he took it from his lips. He flung it on the floor. Clay said, “Once I would’ve wanted pretty bad to think what you just told me was so. But it was more my fault than it was yours. Whatever you did.”

“I served you up!” Morgan cried. He could feel the sweat on his face. “Hollow!” he cried. “Hollow as a damned plaster statue.”

“It doesn’t matter any more,” Clay said. “If it hadn’t been Bob Cletus dead to teach me a lesson, it would have been another. I learned that day a man could be too fast. I thought I had learned it,” he said.

“Damn you, Clay!” he whispered. All at once there was nothing in the world to hold to except this one thing. “Damn you! I will have my way!”

Clay shook his head almost absently. “Do you know what I wish?” he said. “I wish I was some measly deputy in some measly town a thousand miles away. I wish I was not Clay Blaisedell. Morg, you have killed men for my sake – Pat Cletus and McQuown that I know of. But I can’t thank you for it. It is the worst thing you have done to me, because it was forme, and I am more of a fraud of a thing than I knew. Morg – we think different ways, I guess.” He took up his hat; he turned his face away. When he went out he pulled the door quietly but firmly closed behind him.

“Don’t you have the dirty rotten gall to forgive me, damn you to hell!” Morgan whispered, as though Clay were still present. “You didn’t take that away too, did you? You didn’t take that!” He put his hands to his face; his mouth felt stretched like a knife wound. A burst of laughter caught and froze in his bowels like a cramp. “Well, I am sorry, Miss Jessie Marlow,” he said aloud. “But he was iron-mouthed beyond me.” You took me to the last chip, Clay, and won my pants and shirt too, and my longjohns are riveted on and too foul to bear. He shook his head in his hands. He would rather Clay had shot him through the liver than say what he had said, as he had said it, meaning what he had meant by it: We think different ways, I guess.

He pressed his hands harder to his aching face, suffocating in the sour, dead stench of himself. It was a long time before he remembered that he was lucky by trade, and that no one had ever beaten him.

60. GANNON SITS IT OUT

THE sun was standing above the Bucksaws in the first pale green light of morning as Gannon came like a sleepwalker along the echoing planks of the boardwalk, along the empty white street. The inside of the jail was like an icehouse, and he sat at the table shivering and massaging his unwashed, beard-stubbled face. He felt sluggish and unrested, and his blood as slow and cold in the morning chill of the adobe as a lizard’s blood.

He sat staring out through the doorway at the thin sunlight in the street, waiting for the sounds of Warlock waking and going about its Sunday business, and waiting especially for the sound of the early stage leaving town. Today, like every other day, the sun would traverse its turquoise and copper arch of sky; a particular sun for a particular place, it seemed to him, this sun for this place bounded by the Bucksaws and the Dinosaurs, illuminating indiscriminately the righteous and the unrighteous, the just and the unjust, the wise and the foolish. Shivering in the cold he waited for Warlock to waken, and for Kate Dollar to leave, examining the righteousness that both moved and paralyzed him, the injustice he had performed upon himself because of his love of justice. He called himself a fool and prayed for wisdom, and saw only that he could not change his mind, for nothing was changed. He felt as though he were a monk bound to this barren cell by some vow he had never even formulated to himself. He thought of the end of the vow that Carl had known, and accepted. Maybe the only thing changed now was that that end was so much harder to accept.

The first sound he heard was a horn blowing a military call. It was faint, but clear and precise in the thin air – as out of place and improbable as though a forest with stream, moss, and ferns had showed itself suddenly in the white dust of the street. He did not move, holding his breath, as though he had mistaken the sound of his breathing for that other sound. After a while it came again, a bugle call signifying what, rallying or commanding what, he did not know. The brassy notes hung in the air after the call had ended. He rose and moved to the doorway. A Mexican woman with a black rebozoover her head came down Southend Street, and Goodpasture’s mozoappeared, broom in hand, to speak to her as she passed, and then turned and leaned on the broom and stared east up Main Street.

He went back inside the jail and sat down again. Once he thought he heard the sound of hoofbeats, but it was faint, and, when he listened for it, inaudible, as though it had only been some kind of ghostly reverberation along his nerves. He began to think he had heard the bugle only in a half-dream, too. Immediately the brassy, shivering call came again, close now, a different call this time, and now when he hurried out the door there were many people up and down the street, all staring east.

Back of the Western Star he could see the cloud of tan dust rising, and he could hear the hoofs clearly as the dust rolled nearer. Preceding it, riders wheeled into Main Street on the road from Bright’s City. There were ten or twelve of them, in dusty blue and forage caps, one with the fork-tailed pennon on a staff. They came down Main Street at a pounding trot, looking neither right nor left as men hurried out of the street before them, the leader with three yellow Vs on the sleeve of his dark blue shirt, and a dusty-dark, mustachioed face beneath the vicious-looking, flat-vizored cap; the second man holding the pennon staff, and, next to him, the bugler with rows of braid upon his chest. He watched them pass him, and another group appeared, far up the street. The first group trotted to the end of town, wheeled about, and halted. The second turned south down Broadway. A third did not come into Main Street at all, but trotted dustily on past it. Another bugle sounded and more cavalry appeared, this time a much larger body and a mixed one, for there were civilian riders in it. Frozen into his eye for an instant was the image of a huge, uniformed man in a wide, flat hat with one side pinned up, and a white beard blown back against his chest.

Pike Skinner came running across Main Street toward him, shoving his shirttails down into his pants. “What the hell is this, Johnny?”

He could only shake his head. The main body came slowly down Main Street, to halt before the burnt shell of the Glass Slipper. One of the civilians rode on toward him; it was Sheriff Keller. He reined up and dismounted, heavily, and dropped his reins in the dust. Grunting, he mounted the boardwalk, and with a sideways glance at Gannon stamped on into the dimness of the jail. There he slumped down into the chair at the table as Gannon followed him inside. The sheriff wiped his face and the back of his neck with a blue handkerchief and squinted at Pike, who stood in the doorway.

“Glad to’ve seen you, hombre,” he said blandly, and made a slight movement with his head.

Pike started to speak, but changed his mind and went out. Down the street someone was yelling in a brass voice that was drowned in another sudden pad of hoofs.

Gannon felt a sudden wild and rising hope that this was to be some kind of ceremony investing a new county. “What’s the cavalry down here for, Sheriff?”

The sheriff rubbed his coarse-veined red nose. The plating was worn from his sheriff’s star and the brass showed through. “What we forget,” he said slowly, staring at Gannon with his flat eyes. “We get to thinking the general runs things. But there is people to run him too.”

The hope burst in him more wildly still; but then the sheriff said, “Gent named Willingham. Porphyrion and Western Mining Company, or some such. There is a flock of wagons coming down.”

“Wagons?”

“Wagons for miners to ride in.”

“Miners?” he said, stupidly.

“Over to Welltown to the railroad,” the sheriff said. He sucked on his teeth. “And out,” he said, jerking his thumb east. “Out of the territory. Troublemaking miners,” he said, nodding, pursing his lips, scowling. “Ignorant, agitating, murdering foreigners, and a criminal conspiracy, what the general’s general says. Willingham, that is.” He sighed, then he scowled at Gannon. “This Tittle a friend of yours too, son? That was what tore it.”

A crutch-tip cracked on the planks. Judge Holloway came in, red-faced and panting. “Oh, it’s you, Keller!” the judge said. “Oh, you have come down to Warlock at last, have you?”

“Uh-huh,” Keller said. “Sit,” he said, vacating the chair grudgingly, and moving his bulk to the other. The judge sat down. His crutch got away from him, and clattered to the floor.

“Will you tell me what damned dirty devilment is going on here, Keller?”

“Run out of Apaches,” the sheriff said. His fat face looked tired and disgruntled. In the street Gannon saw a man running, looking back over his shoulder. He started out. “Here!” Keller barked. “Come back here, boy! You are going to have to pay this no mind.”

“Pay what no mind?”

“What are you saying about Apaches, Keller?” the judge said.

“Why, they are all cleaned out, so now it is Cousin Jacks to take out after. New flag; it has got Porphyrion and Western wrote on it. Wagons coming. All those striking ones are going to get hauled up to Welltown and a special train is going to haul them back east somewheres and dump them.”

“MacDonald,” the judge whispered.

“Why, surely, MacDonald. Only he has got his big brother along, name of Willingham. Out from Frisco. Willingham has thrown a scare into old Peach something terrible.”

The judge began to hawk as though he would strangle. The sheriff rose and pounded him on the back. “Son,” he said to Gannon. “You should have snatched down on that Tittle, what you should have done. You let me down, boy, and I got ordered down here the same as some tight-britches trooper.” He pounded the judge on the back once more, and then reseated himself. Gannon leaned back against the wall.

“They can’t do it!” the judge cried. “He is crazy!”

“Didn’t you people down here in Warlock know that? But he can surely do it. Colonel Whiteside was arguing and stamping around, how he couldn’t do it; and Willingham giving it to him he had damned well better. I heard Whiteside telling him Washington’d have his ears for it. But when Peach gets a bee in his bonnet he moves and if you think he can’t do it, you just watch him.”

Keller took off his hat, ran a hand back over his head, sighed, and said, “Whiteside is a nice old feller for a colonel, and thinks high of Peach too. He says all he wants is for Peach to go out well thought of, which he is near to doing – and this will ruin him for sure. But Peach thinks how Willingham can do him some good in Washington some way, and anyway Willingham is claiming this is armed rebellion against the U.S. down here, and up to Peach to stop it. Why, they are going to round up these jacks like a herd of longhorns and ship them out in cattle cars, and it is a crying shame.” He extended a long, spatulate finger. “But judge,” he said, “and boy: there is nothing to do about it.”

The judge slid the drawer open against his belly and worked his bottle of whisky out of it. He cracked it down on the table before him. He said, “We are overrun with Philistines!”

“Save some of that for me,” the sheriff said. “I rid drag all the way down here.”

Gannon leaned against the wall and stared at the sheriff’s face. “What are you here for, Sheriff?”

The sheriff took the bottle the judge handed him, and drank. His belly began to shake; he was laughing silently. He handed the bottle back and winked. “Why, I am to clean things out down here,” he said. “You and me, son. Why, we are to fill up one of those wagons ourself. Road agents, rustlers, murderers, and such trash; we are to round up a bagful. Old Peach heard somewhere that things’ve got a little out of hand down here.”

Gannon turned to watch a squad of cavalry ride slowly by, spaced to fill the street from side to side, carbines held at the ready. “Blaisedell,” the sheriff said, and laughed.

Gannon’s head swung back. He heard the judge draw in a sharp breath. The sheriff’s belly shook again with silent laughter. “Shoot him down like a dog if he don’t go peaceable,” the sheriff said. “And that’s when I unpinned this wore-out old badge here and handed it in. And said I had just retired, being too old for the job.”

“Great God!” the judge said.

“MacDonald said how Blaisedell went and interfered with Johnny here in the performance of his duty, which was Tittle,” Keller went on. “Only that’s not all of it. Peach don’t like anything about Blaisedell. Blaisedell’s been stealing his thunder. There is a lot of bad things being said about Blaisedell now, too, to give the crazy old horse his due. Some talk he went down and settled McQuown kind of backside-to.”

“It is a lie!” the judge said, wearily. “Well, what happened? I see you have your badge back. Did you decide to shoot him down?”

“Worked out so I don’t have to,” Keller said, grinning. “Whiteside talked him some turkey on that one. Told him how Blaisedell was held innocent up in court, and how Peach would just make him more of a thing down here than he is already if he tried to run him out, and Blaisedell got shot or Igot shot. What he said to do was, since the Citizens’ Committee down here had hired Blaisedell and they wanted a town patent pretty bad, was tell them they could have it if they got rid of Blaisedell. It was slick to see Whiteside getting around him on that, and it worked too. Except—” He looked suddenly depressed. “Except if he don’t go, it is back to me again. But I can always resign,” he said, brightening. “Pass over that bottle again, will you, Judge?”

The judge handed it to him. “We are a bunch of vile sinners,” he said in a blurred voice. “But I am damned if we deserve this. What about Doc Wagner, Keller? Does Peach mean to have him transported too?”

“Yep,” the sheriff said. “Now, you just sit down, Judge. There is not a thing in the world you can do. Johnny!” he snapped. “Don’t sneak that hand up there to be unpinning that star, or I will load you on my wagon first off and you will wait it out in the hot sun till I catch the rest, which might be a while. Now you just calm yourself. All the arguing and maneuvering to be done’s been done already. I have seen Peach take out after Whiteside with that sword of his, fit to take his head off. Don’t go trying to interfere with him.”

“He can’t do that to those poor damned—”

“He can,” the sheriff said. “What was you going to do to stop it, son?”

Peter Bacon stuck his head in the door. “Johnny, are you going to stand by and let those blue-leg sons of bitches—” He stopped, staring at the sheriff. “My God, are you here, Keller?” he said, incredulously.

“I’m here,” the sheriff said. “And how’s things going out there?”

Peter’s brown face wrinkled up as though he were going to cry. “Sheriff, they are rounding up those poor fellows from the Medusa like—”

“Going well, huh?” the sheriff said. “Well, drop in some later and see us again, Bacon. Pass me that bottle, Judge.”

Peter stared at the sheriff, and turned and looked Gannon up and down. Then he withdrew. Keller tilted the bottle to his lips. Gannon saw the sheriff’s hand, lying on the table before him, clench into a fist as there was a burst of shrill shouting down the street.

Gannon started toward the door.

“Don’t even look, boy,” the sheriff said heavily. “You might turn into a pillar of salt or something.”

“Salt’s not what I’m worth. Or you.”

“I know it, boy. I never said otherwise. But you can’t interfere with the cavalry, and the military governor. During maneuvers,” he added. “That’s what they are calling it; maneuvers.”

“And you are supposed to maneuver down to San Pablo?” the judge asked.

“Supposed to. I guess I won’t rush things, though.”

“You might do well to rush. From what we hear they are all down raiding the Hacienda Puerto range right now.”

“Rush,” the sheriff said, nodding. Then Keller looked at Gannon again with his sad eyes. “Nothing you can do, boy,” he said. “Nor any man. Just stand steady and let it go by. He’s put his big foot in it now, and who knows but things might change, maybe, because of this.”

“I have thought,” the judge said bitterly, “that things were so bad they couldn’t get any worse. But they have got worse today like I wouldn’t believe if I didn’t hear it going on. And maybe there is no bottom to it.”

“Bottom to everything,” the sheriff said, holding up the bottle and shaking it. Through the door Gannon watched a young lieutenant cantering past on a fine-looking sorrel, followed by a sergeant. He slammed his hand against his leg.

“Hold steady now,” the sheriff said.

“Yes, learn your lessons as they come your way,” the judge said. “And when you have learned them all they can stick red-hot pokers in your wife and babies and you will only laugh to see it. Because you will know by then that people don’t matter a damn. Men are like corn growing. The sun burns them up and the rain washes them out and the winter freezes them, and the cavalry tramps them down, but somehow they keep growing. And none of it matters a damn so long as the whisky holds out.”

“This here’s gone,” the sheriff said. “Go cut some of that corn and stir up some more mash, Judge. Say, did you people get any rain down this way?”

A rumble of bootheels came along the boardwalk. Old man Heck came in the door, his chin whiskers bristling with outrage, and Frenchy Martin and four others, of whom Gannon recognized only one named Daley, a tall, mild, likeable miner. Then he saw the doctor, with a trooper holding his arm. The doctor’s face was grayer than ever, but his eyes were bright. There followed two other troopers, a sergeant, and Willard Newman, MacDonald’s assistant at the Medusa, who shouldered his way inside past troopers and miners.

“Deputy, these men are to be locked up until the wagons get here.”

“Lickspittles, all of you!” the doctor said.

“Now, Doc, that don’t do no good,” Daley said.

“MacDonald is afraid to look me in the face so he sends his lickspittles!”

Daley thrust himself between the doctor and Newman, as Newman cursed and raised a hand. “You!” the sergeant said, to Newman. “You mistreat the prisoners and I’ll drink your blood, Mister!”

“That’s the sheriff!” one of the miners said, and Gannon saw Keller’s face redden. The doctor moved stiffly inside the cell, and the others followed him.

“I hope you soldiers are proud of your uniforms today!” the judge said, raising his voice above the shuffling of boots.

“You should be in here with me, George Holloway!” the doctor called, standing with the miners in the cell. “This is a thing every man who likes to think himself of a liberal persuasion should know for himself. We belong—”

“I will stay out and drink myself to death instead,” the judge said, with his head bent down.

“Lock them up, Johnny,” the sheriff said. He held the bottle up, studied it, and then handed it back to the judge.

Newman kicked the door shut.

“I’ll not!” Gannon said, through his teeth.

The sergeant turned to look at him; he had a sour, weatherbeaten face and thick graying sideburns. Newman glared at him. “Lock them up, Deputy!”

“By whose orders?”

“General Peach’s order, you fool!” Newman cried. “Will you lock these sons of bitches up before I—”

“Not in my jail!” He thrust between the sergeant and Newman, snatched the key ring from its peg, and retreated to stand against the wall where the names were scratched. He put his hand on the butt of his Colt. The sheriff stared at him; the judge averted his face.