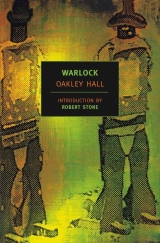

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

February 1, 1881

THE latest bag of road agents has been acquitted by a Bright’s City jury. There is high feeling here, and those who journeyed to Bright’s City to give evidence or as spectators are exceedingly violent in their anger against judge, jury, lawyers, Bright’s City in general, and Abraham McQuown in particular. Since Benner was the only bandit positively identified by his victims, the defense mounted the outrageous presumption that the other two were consequently innocent, and, that since both of these swore that Benner had been with them all day and that they had engaged in no crimes whatsoever, then Benner was also innocent. The witnesses who identified Benner were tricked into admitting that the main factor in their identification was his small stature, which was made to seem ridiculous. The posse itself, it was claimed, was responsible for Phlater’s death, since it had begun firing wildly at the “innocent cowboys” as soon as they were within range, and the Cowboys plainly could not be blamed for defending themselves from such a vicious assault. It was implied even further that the whole affair was staged by “certain parties,” and the strongbox carefully disposed where it would implicate the poor Cowboys most foully.

It is said that the prosecution was pursued with less than diligence. It is also said that judge and jury were bribed, and that the courtroom was crowded with McQuown’s men brandishing six-shooters and muttering threats. Along the way my credulity begins to fail, amongst all this evidence of perfidy, but the fact remains that the three men have been freed. They rode through here yesterday on their way back to San Pablo. They encountered a sullen and most unfriendly Warlock, and had sense enough not to linger here in their triumph.

I think next time it may be very difficult to discourage a lynching party from its objective.

Still, certain good has come out of the affair. Public opinion, as it did when our poor barber was killed and Deputy Canning driven out of town, has again congealed, so that the Citizens’ Committee feels itself in not so exposed and arbitrary a position in trying to administer some kind of law in Warlock.

The Citizens’ Committee has not met yet. We are not in a hurry to face the situation, and feel it best to move slowly. The question foremost in everyone’s mind is, of course, whether or not Blaisedell should be called upon to post the “innocent Cowboys” out of town, and, insofar as I can see, the great majority of the Citizens’ Committee, and of Warlock itself, is for this. There is much talk of a Vigilante Army convened to ride upon San Pablo and “clean the rascals out.” There is also talk of posting McQuown and allhis men, and backing up Blaisedell in whatever action might ensue with a vigilante troop, which would be only operative within Warlock and for this one purpose.

As to the wholesale posting, you may hear it being argued on every hand, but with qualifications almost as numerous as the arguers. I think some of us are obsessed with the pleasure and presumption of dictating Life & Death.

There are also some who seem to be having grave second thoughts about the whole system of posting. Will Hart, I notice, is beginning to sound remarkably like the judge in his arguments. True, these say, posting worked in the case of Earnshaw, who is definitely reported to have left the territory – but is it not asking for trouble? Does not posting actually make it a point of honor that a man come in to fight our Marshal? What if a number come in against him at once and he is killed – are we not then still more at the mercy of the outlaws? What, if this be carried too far, is to prevent the enemies of each among us from seeing that he himself is posted?

I must face the fact, of course, that Public Opinion is not so unanimous as I would like to think. There are issues at stake, but as too often happens, we are apt to look to men as symbols rather than to the issues themselves. There are two sides here; one is Blaisedell, the other McQuown. So, alas, have the people chosen to see it. Blaisedell is, at the moment, the favored one by far; the profanum vulgusis solidly for him, and, as evinced by the lynch mob (which, curiously, Blaisedell had a large hand in putting down), against McQuown and the “innocents.” The Citizens’ Committee, of course, is behind Blaisedell too, but, as is usual when some are more violently partisan than we are, we edge away a little and restrain our own enthusiasms.

Still, McQuown retains some of his adherents. Grain, the beef butcher, who, I am sure, buys stolen beef from McQuown, remains loyal to him. Ranchers, such as Blaikie, Quaintance, and Burbage, view the outlaw as a necessary evil, point out that their problems would be greatly increased without the presence of a controlling hand, and in any case are apt to view Blaisedell, possibly because he is a townsman and an agent of townsmen, with suspicion.

I do not think the Citizens’ Committee intends to do more than post the three road agents (or more probably four, including Friendly) out of town, but that remains to be seen. There is some talk of posting at the same time a chronic malcontent and agitator among the miners, but I feel this would confuse the present issue. I presume a meeting will be called by this week’s end, at the latest.

February 2, 1881

I am sorry for Deputy Gannon. He must know that his brother’s fate is being decided, all around him, by the jury this town has become, and he looks gaunt and haunted, and as though he has not slept in days. He, Schroeder, and the Marshal have not had much to occupy their time of late. Warlock is in a fit of righteousness, and men are exceedingly careful in their actions. The presence of Death does not make us feel pity for the dead or the condemned, but only a keen awareness of our own ultimate end and a determination to circumvent it for as long as possible.

February 3, 1881

A despicable rumor is being circulated, to the effect that the Cowboys are truly innocent, and that the bandits actually were Morgan and one or more of his employees from the Glass Slipper; that Morgan was seen riding furtively back to town not long after the stage arrived here, etc. This is an obvious tactic of McQuown’s adherents here to backhandedly attack Blaisedell, as well as of Morgan’s enemies, of whom there are a great number. Why Morgan should have taken up road-agentry, when he has a most lucrative business in his gambling establishment, has not been stated.

Morgan is certainly roundly hated here, with good reason and bad. I might venture to say that unanimity of opinion comes closest to obtaining in Warlock as regards dislike of him. Personally, I think I would choose him over his competitor, Taliaferro, and I am sure that Taliaferro relieves his customers of their earnings no less rapidly or crookedly than Morgan. Yet Morgan does it with a completely unconcealed disdain of his victims and their manner of play. His contempt of his fellows is always visible, and his habitual expression is that of one who has seen all the world and found none of it worth while, least of all its inhabitants. He has evidently acted viciously enough upon occasion too. There was the instance of a Cowboy who worked for Quaintance, a handsome and well-liked young fellow named Newman, who, unfortunately, had larcenous tendencies. He stole three hundred dollars from his employer, which he promptly lost over Morgan’s faro layout. Quaintance learned of this and applied to Morgan for the return of the money. Morgan did return it, possibly under pressure from Blaisedell, but dispatched one of his hirelings, a fellow named Murch, after young Newman. Murch caught him in Bright’s City and, following Morgan’s instructions, beat the boy half to death.

Like others of prominence here Morgan has been the object of many foul, and, I am sure, untrue tales. Unlike others, he seems pleased and flattered by this attention (I suppose this furnishes further evidence to him in support of his opinions of his fellow man), and has even sometimes hinted that the most incredible accusations of him may be true.

Because of all this, however, Blaisedell, in his fast friendship with Morgan, is rendered most vulnerable. I hope Morgan does not become the Marshal’s Achilles’ heel.

18. THE DOCTOR ARRANGES MATTERS

THE doctor hurried panting up the steps of the General Peach and into the thicker darkness of the entryway. He rapped on Jessie’s door; his knuckles stung. “Jessie!”

He heard her steps. Her face appeared, pale with the light on it, framed in curls. “What’s the matter, David?” she said as she opened the door wider for him. He moved in past her. A book lay open on the table, a blue ribbon across the page for a bookmark. “What’s the matter?” she said again.

“They have instructed him to post five men out,” he said, and sat down abruptly in the chair beside the door. He held up his hand, spread-fingered, and watched it shake with the sickening rage in him. “Benner, Billy Gannon, Calhoun, and Friendly. Andhe is to post Frank Brunk.”

She cried out, “Oh, they have not done that!”

“They have indeed.”

She looked frightened. He watched her close the book over the blue ribbon. She stood beside the table with her head bent forward and her ringleted hair sliding forward along her cheeks. Then she sank down onto the sofa opposite him.

“I have talked myself dry to the bone,” he said. “It did no good. It was not even a close vote. Henry and Will Hart and myself – and Taliaferro, of course, who would not want to offend the miners’ trade. The judge had already left in a rage.”

“But it is a mistake, David!”

“They did it very well,” he went on. “I will admit myself that Brunk is a troublemaker. His activities could easily lead to bloodshed. Lathrop’s did. Brunk has been posted to protect the miners from themselves – that is the way Godbold put it. And to protect Warlock from another mob of crazed muckers running wild and smashing everything – that is the way Slavin put it. What if they fired the Medusa stope? Or all the stopes, for that matter? I think the only thing Charlie MacDonald had to say in the matter was what would happen to Warlock if the miners, led by Brunk, succeeded in closing all the mines out of spite? Evidently they are thought entirely capable of it.”

He beat his fist down on the arm of the chair. And so we fell into the trap we had set for ourselves when we brought Blaisedell here, he thought. “It was so well done!” he cried. “But Jessie, if you had been at the meeting, they could not have done it.”

“Posting men from Warlock is nothing I can—”

“You should have gone!”

“I will go to see every one of them now.”

“It will do no good. Each one will lay it on the rest.” He slumped back in the chair; he told himself firmly that he would not hate Godbold, Buck Slavin, Jared Robinson, Kennon, or any of the others; he would only try to understand their fears. What angered him most was the knowledge that they were, in part, right about Frank Brunk. But he knew, too, that he himself was now inescapably on the side of the miners. Heaven knew that a blundering, stupid leader such as Brunk was no good to them; but Brunk was all, at present, that they had. It was as though he had, at last, come face to face with himself, and, at the same moment, saw that the man who was his own mortal enemy was Charles MacDonald of the Medusa mine.

“Poor Clay,” he heard Jessie whisper.

“Poor Clay!Not poor Frank? Not those poor fellows—” He stopped. She had said it was a mistake, and he saw now what she meant. The miners’ angel had become the guardian of Blaisedell’s reputation. All at once he could regard her more coldly than he had ever done before.

“Yes,” he said. “It is a terrible mistake. Do you think you can persuade Blaisedell that he must do no such a thing?”

“I must try,” she said, nodding as though Clay Blaisedell were the object of both their concerns.

“Yes,” he said. “For if he does this to Brunk, how is he any better than Jack Cade, who was hired to do it to Lathrop? And you know what Frank is like as well as I do. I think he would not go if ordered to, and how would Clay deal with him then? Frank is no gunman.”

He glanced at her from under his brows. She was sitting very stiffly, with her hands clasped white in her lap. Her great eyes seemed to fill the frail triangle of her face. “Oh, no,” she said, with a start, as though she had not been listening but knew some reply was called for. “No, he can’t be allowed to do it. Of course he can’t. It would be terribly wrong.”

“I’m glad we agree, Jessie.”

She frowned severely. “But if I can’t persuade him to – to disobey the Citizens’ Committee, then Frank will have to go. That’s all there is to it. He will go if I ask him to, won’t he, David?”

He did not know, and said so. She announced decisively that she wished to speak with Brunk first, and he left her to find him. In the entryway, with her door closed behind him, he stood with a hand to his chest and his eyes blind in the solid dark. He had thought she was in love with a man, but now he saw, with almost a pity for Blaisedell, that she was in love merely with a name, like a silly schoolgirl.

The doctor moved slowly along the tunnel of darkness toward the lighted hospital room. The faces in the cots turned toward him as he entered. Four men were playing cards on Buell’s cot – Buell, Dill, MacGinty, and Ben Tittle. The boy Fitzsimmons stood watching them, with the thick wads of his bandaged hands crossed over his chest.

There was a chorus of greetings. “What about the road agents, Doc?” someone called to him.

“Did Blaisedell post those cowboys yet?”

He nodded curtly, and asked if anyone had seen Brunk.

“Him and Frenchy’s up in old man Heck’s room, I think,” MacGinty said.

“You want him, Doc?” Fitzsimmons said. “I’ll go tell him.” He went out, his bandaged hands held protectively before him.

“Hey, Doc, how many got posted?” a man called.

“Four,” he said. Someone laughed; there was a swell of excited speculation. He said. “Ben, could I see you for a minute?”

He stepped back out into the dark hall. When Tittle came out, he told him to go find Blaisedell in half an hour. Then he went back down to Jessie’s room; she glanced up at him and apprehensively smiled when he entered, and he went over and put out a hand to touch her shoulder. But he did not quite touch it, and, as he stared down at the curve of her cheek and the warm brown glow of the lamplight in her hair, his throat swelled with pain, for her. He turned away and his eye caught the dark mezzotint of Bonnie Prince Charlie, kilted, beribboned, gripping his sword in noble and silly bravado.

He heard heavy footsteps descending the stairs. “Come in, Frank,” he said, as Brunk appeared in the doorway.

Brunk came inside. “Miss Jessie,” he said. “Doc. What was it, Doc?”

“The Citizens’ Committee has voted to have you posted out as a troublemaker,” he said, and saw Brunk’s eyes narrow, his scar of a mouth tighten whitely.

“Did they now?” Brunk said, in a hoarse voice. All at once he grinned. “Is the marshal going to kill me, Miss Jessie?”

“Don’t be silly, Frank.”

Brunk held out his hands and looked down at them. Then, with a ponderous, triumphant lift of his head Brunk looked up at the doctor and said, “Why, I expect he is going to have to, Doc. Do you know? The boys wouldn’t move for Tom Cassady, but maybe they will if—”

“Don’t be a fool!” he said.

“Now, Frank, you are to listen to me,” Jessie said, in a crisp, sure voice, and she rose and approached Brunk. “I am going to ask him not to do this thing, whatever the Citizens’ Committee has decided. But if I—”

“Ah!” Brunk broke in. “The miners’ angel!”

“You will be civil, Brunk!”

A flush darkened Brunk’s face. He took hold of his forelock and pulled his head down, as though in obeisance. “Bless you, Miss Jessie,” he said. “I am beholden to you again.”

“I have promised to try,” Jessie went on. “But as I was saying when you interrupted me – if I cannot, then you must promise to leave.”

“Run for it?” Brunk said. “Run?”

“Do you have to go out of your way to be offensive, Brunk?”

“Doc, I am trying to go out of my way to be a man! But she won’t let me, will she? She will nurse me off this. She is too heavy an angel! She wouldn’t let Tom Cassady die when he was begging to. She won’t let me—” He stopped, and his mouth drew sharply down at the corners. “If I had courage enough,” he said. “But maybe I don’t.”

“I don’t know what you are talking about, Frank.”

“I don’t know what I am talking about either. Because they would not move even for me, and I would be a fool. But what would youdo, Doc?”

“I think I would do as she asks,” he said, and could not meet Brunk’s eyes.

“Why, I have to, don’t I?” Brunk said. “She has kept me since I was fired at the Medusa. Put up with me, and fed me. But, Miss Jessie – you said Jim Lathrop didn’t have courage enough. Why won’t you let me have it? Maybe I have got enough.”

“I’m sure I don’t know what you are talking about,” Jessie said. “But if you will not do this for your own sake – and I understand that men must have their pride, Frank – then you must do it for mine. I hope it will not be necessary.”

Brunk stared at her. “Why, I would be a fool, wouldn’t I?” he said in his heavy, infinitely bitter voice. “And ungrateful too, since it is for your sake, Miss Jessie. But don’t you see, Doc?”

The doctor could say nothing, and Jessie put a sympathetic hand on Brunk’s arm. But Brunk drew away from her touch and backed out the door. His heavy tread slowly remounted the stairs.

“I don’t understand,” Jessie said, in a shaky voice.

“Don’t you?” he said. “Brunk was just wishing he might be a hero, and knows he cannot be. It is difficult for a man to bring himself to be a martyr when he is afraid he might look a fool instead. Do you think you can persuade Blaisedell?”

She did not answer. She was staring at him strangely, tugging at the little locket that hung around her throat.

“It is very important that you do,” he went on. “Because of what the miners would think of you if Blaisedell went through with this. Whether Brunk fled, or not. And because of what everyone would think of Blaisedell.”

He felt a blackguard; he turned so as to confront himself in her glass, and saw there a short, gray man with bowed shoulders in a shabby black suit, undistinguished looking, not handsome, not heroic in any way, almost old. The eyes that gazed back at him from the glass looked like those of a man with a dangerous fever.

“There is Clay,” Jessie whispered, as footsteps came along the boardwalk outside her window.

“I wish you luck with him, Jessie,” he said. He went out into the entryway just as Blaisedell entered; a little light from Jessie’s open door gleamed in the marshal’s hair as he took off his hat.

“Evening, Doc,” he said gravely.

“Pardon me,” the doctor said, and Blaisedell stepped aside so that he could pass.

Outside he stood on the porch for a moment, breathing deeply of the fresh, cool air, and gazing up at the stars bright and cold over Warlock. Behind him he heard Blaisedell say, “Did you want to see me, Jessie?” Quickly the doctor descended the steps to get out of earshot. He went up the boardwalk, across Main Street, and on up toward Peach Street and the Row.

19. A WARNING

IN THE jail Carl Schroeder, Peter Bacon, Chick Hasty, and Pike Skinner were talking about the posting, while at the cell door Al Bates, from up valley, watched them with his whiskered chin resting on one of the crossbars.

“You suppose the news got down to Pablo yet?” Hasty asked.

“Dechine was in,” Bacon said, from his chair at the rear. “And went back down valley yesterday. I expect he’d take it as neighborly to stop in and tell McQuown the news on his way home.”

“They won’t come,” Schroeder said, hunched over the table, scowling, gouging the point of a pencil into the table top.

Hasty said, “I guess Johnny’s plenty worried Billy’ll show.”

“Worried of getting in bad with McQuown, mostly,” Skinner said. “He—”

“You!” Schroeder said. “I am sick of hearing you picking at Johnny Gannon!” He flung the pencil down. “He come in here and put on that star, youdidn’t! You quit fretting at him, Mister Citizens’ Committee Skinner!”

Peering up at Skinner from under his hat brim, Hasty said, “Is MacDonald going to see the Committee fires Blaisedell for saying them no on that jack, Pike?”

“He did right,” Skinner said, with a sour face. “Nobody’s thought of firing him. MacDonald fired that son of a bitch Brunk how long ago, but he still hangs around trying to drum up a fuss. It’s the Committee’s business to post out troublemakers, but Blaisedell can’t go against a dumb jack that doesn’t know one end of a Colt from the other.”

“Old Owen was saying he heard some muckers talking that if the Committee fired Blaisedell over it, the miners would get together and hire him themself,” Schroeder said. “And put him to post MacDonald first thing.”

The others laughed.

“There is talk Miss Jessie had a hand in the marshal changing his mind about Brunk,” Hasty said.

“Lot of talk up our way them two is going to come to matrimony right quick,” Bates said from the cell. “Make a fine-looking couple.”

Nobody spoke for a time, and finally Bacon sighed and said, “You suppose the four of them is going to come against him? Or not?”

“They won’t come,” Schroeder said again, grimly. He began to jab his pencil at the table top once more.

Standing in the doorway Skinner worriedly shook his head. He turned as there was an approaching cracking sound on the board-walk.

“Here comes old Judge,” Bates said. “Charging along on that crutch of his to give everybody pure hell again.”

The judge entered past Skinner. With his shoulders hunched up by the crutch and his claw-hammer coat hanging loose, the judge looked like a big, awkward, black bird. He halted and his bloodshot eyes glared fiercely around the jail. “Where’s the deputy?”

“Here!” Schroeder said. He raised himself reluctantly from the judge’s chair, and leaned against the cell door.

“Not you. The other one.”

“Sleeping, I guess. He was on late last night.”

“There’s no sleep any more,” the judge said. He shifted his weight from the crutch to a hand braced on the table, and sat down with a grunt. His crutch clattered to the floor.

“Aw, please, Judge,” Hasty said. “Leave us sleep sometimes. We got little enough else.”

The judge scraped his chair around to face the others. “You would sleep through the roof of the world caving in and not even know it,” he said. He removed his hat, using both hands, and set it before him. He glared around the room.

“By God, you stink, Judge,” Skinner said. “Why don’t you come down to the Acme and me and Paul and Nate’ll scrape you down in the horse trough?”

“I don’t stink like you all stink.” The judge rubbed at his eyes, muttering to himself. “Where is Blaisedell?” he said suddenly. “He is running from me!”

Everyone laughed. “Laugh!” the judge cried. “Why, you poor, ignorant pus-and-corruption sons of bitches, he is afraid of me!”

“He’s went for his gold-handles, Judge,” Schroeder said. “Then he’ll show.”

They laughed again, but the laughter broke off abruptly as a shadow fell in the door. Blaisedell came in, bowing his head a little as he stepped through the doorway. He was coatless, wearing a clean linen shirt and a broad, scrolled-leather shell belt, with a single cedar-handled Colt holstered on his right thigh.

“Judge,” he said. He nodded to each of them. “Deputy. Boys. Looking for me, Judge?”

“I was,” the judge said, and Bates snickered. The judge said, “I am warning you, Marshal. You are now standing naked and all alone. The Citizens’ Committee has gone and disqualified itself plain to everyone from pretending to run any kind of law in this town. Ordering you to something that wasn’t only illegal and bad but was pure damned outrage besides. And you have gone and disqualified yourself from them by refusing to do it. Now!” he said, triumphantly.

Blaisedell took off his hat and idly slapped it against his knee. He looked at once amused and arrogant. “You are speaking for who, Judge?” he asked politely.

“I am speaking—” the judge said. His voice turned shrill. “I’m speaking for– I’m just warning you, Marshal!”

“Listen to him go at it!” Bates whispered. “By God, he is a real Turk, that old Judge.”

Blaisedell glanced at him and he looked abashed.

“For what you have done,” the judge went on, more calmly, “you have run up a ukase on those four boys all by yourself now.”

“Pardon?” Blaisedell said.

“Now, hold on, Judge—” Schroeder began.

“Ukase!” the judge said. “That is a kind of imperial king I-want. What the king does when he makes the rules as he goes along. You have run one up the flagstaff and yourself with it. For what was behind you has blown itself out to nothing, and you have walked off away from it anyhow. I told you it was the only thing you had! And a poor thing, but even it gone now.”

“Don’t listen to the old cowpat, Marshal,” Skinner said placatingly. “He has got a load on and raving. He is not talking for anybody. He is surely not talking for the Citizens’ Committee.”

“I am talking for his conscience,” the judge said. “If he can hear it talking in his pride!”

“Why, I can hear you, Judge,” Blaisedell said. He stood looking down at the judge with his eyebrows hooked up, and his mouth, beneath the fair mustache, flat and grave. “But saying what?”

“Saying there is nothing you are accountable to any more,” the judge said. “You have got no status, you have chucked it away. No blame to you for that, Marshal, but it is gone. What I am saying is you can’t post those four fellers out. You are no law-making body. You can’t make laws against four men. Neither could the Citizens’ Committee, but they had a better claim than you. Mister Blaisedell, you are running up a banishment-or-death ukase and it is illegal and outlaw and pure murder. There is no law behind you!”

“Fry your head in your God-damned law!” Skinner said. “We saw enough of it, up in Bright’s City.”

The judge massaged his eyes with his hands again. Then he squinted cunningly up at Skinner. “You saw lynch law here in town just before that,” he said. “You didn’t like that either, did you? Liked that some less, didn’t you?” he cried. Pressing down on the table top, he half-raised his thick body, and cords stood out on the sides of his neck. “Did you like that mob? I tell you he is a one-man lynch mob if he goes on like he is headed!”

“By God!” Bates whispered, admiringly. “I bet he could beller a brick wall down.”

The judge sank back into his seat. Blaisedell’s intense blue stare inspected, one by one, the men in the room. They fastened last upon the judge again, and he said, coldly, “One man is a different thing from a mob. If a man runs with a pack like that he is only a part of the pack and the whole thing hasn’t got a brain or anything. I say what you said just now is foolishness, and I think you know it. I am not scared of myself so I have to look around every second to make sure the Citizens’ Committee is standing right behind, nodding to me. Or the town either,” he said, glancing at Hasty. “Because in a thing like this I know best and can do best by myself.”

“You have said it out loud!” the judge whispered. “You have said it. You have set yourself above the rest in your pride!”

Blaisedell’s face tightened. “If I am hired to keep the peace in this town,” he said, slowly and distinctly, “why, I will do it and the best I can. Judge, I would keep those four birds out of town whether anyone told me to or not.”

“You are not going to keep them out! You are going to kill them! You are going to shoot them down dog-dead in the street, or them you. Keep the peace! Why, if that don’t make somebody a murderer and somebody dead that didn’t need to be then I can’t see across my nose! Keep the peace! Why, you will bust it wide open with your hail-to-the-king ukase!”

“Maybe,” Blaisedell said. “But most likely they won’t come in.”

“They will come!” the judge said. “I’ll tell you why they will come. Because now they are guilty-as-sin road agents to every man, and they know it. They are that if they stay out, and yellow-bellies besides. If they come in they will think they are honest-to-genuine, gilt-edged heroes proving they are innocent to all, and striking a blow for freedom too. Men have died for that many’s the time, and God bless them for it!”

“They know better than to come,” Skinner said.

“They will have to come. And you, Mister Marshall of Warlock Blaisedell, have made it so. There is no way out of it. So you will have to kill them. And that will put you wrong. You will fall by it, son.”

“Don’t call me son, Judge,” Blaisedell said, very quietly. A vein began to beat in his temple.

The judge said in a blurred voice, “Marshal, if you understand me and go your way anyhow, God help you. You will be killing men out of pride. You will be doing foul murder before the law, and you will stand trial in Bright’s City for it or these deputies here ought to throw their badges in the river. For you will be an illegal black criminal and outlaw and murderer with the blood fresh on you as bad as any of McQuown’s and worse, and every man’s hand should be against you. Murder for pride, Marshal; it is an ancient and awful crime to go to book for.”

Blaisedell backed up a step, to stand in the patch of sunlight just inside the door. He put his hat back on and tapped it once, and glanced around the jail again. This time no one met his eyes.

Blaisedell said gravely, “Maybe somebody will get killed, Judge. But that is between them and me, for who else is hurt by it?”

“Every man is,” the judge whispered.

Blaisedell flushed, and the arrogant, masklike expression came over his face again. But his voice remained pleasant. “You have been going on about pride like it was a bad thing, and I disagree with you. A man’s pride is about the only thing he has that’s worth having, and is what sets him apart from the pack. We have argued this before, Judge, and I guess I will say this time that a man that doesn’t have it is a pretty poor specimen and apt to take to whisky for the lack. For all whisky is, is pride you can pour in your belly.”