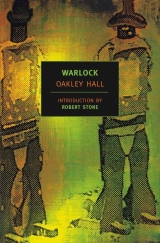

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

IN HIS office at the rear of the Glass Slipper, Tom Morgan changed into a clean linen shirt and tied his tie by the dim last dregs of daylight. From the mirror the image of his pale face with the silver-white sleek hair and the black slash of mustache gazed back at him, expressionless and shadowy. He put on a bed-of-flowers vest, his shoulder harness, and short holster that carried his Banker’s Special flat against his side, and his fine black broadcloth coat.

Then he poured a quarter of an inch of whisky into a glass from the decanter on his desk, and rinsed it through his mouth, gazing up now at the dull painting of the nude woman sprawled lushly on a maroon coverlet that hung, slanting sharply, on the wall over the door into the Glass Slipper. He raised his empty glass to her in a formal salute, and swallowed the whisky in his mouth. As though it had been a signal, the piano began to fret and tinkle beyond the door, the notes muted sourly in the increasing busy hum of evening.

He went out into the Glass Slipper. The big chandelier was still unlighted. To his right the long bar was lined with men’s backs, the mirror behind it lined with their faces, but the miners had not started coming in yet and only one faro layout was going. Two barkeeps were hustling whisky and beer. The professor sat erect and narrow-shouldered at the piano, his hands prancing along the keys, a glass of whisky before him. He turned and smiled nervously at Morgan, the little tuft of whiskers on his chin popping up. Murch, brooding over the faro layout, his shotgun lying across the slots in the arms of his highchair, nodded down at him. Morgan nodded back, and, as he passed on, nodded to Basine, and to the case keeper, and to the dealer, shadowy-eyed in his green eyeshade; to Matt Burbage and Doctor Wagner. He sat down at an empty table in the corner to the left of the louvre doors, and raised two fingers to one of the barkeepers.

There was a deck of cards on the table, and he began to sort the cards by suit and number, his pale, long hands moving rapidly. When he had finished the sorting he quickly cut, recut, and shuffled. He frowned as he examined the result. The barkeeper arrived with a bottle and two glasses, but he did not look up, sorting, cutting and shuffling as before. This time the cards had reformed in proper order. He regarded them more with boredom than with pleasure. He was thirty-five, he thought suddenly, for no reason; half done. He poured a little whisky in his glass and touched it to his lips, but only to taste it, and his eyes glanced around the Glass Slipper. It was the same, here as in Fort James, here as anywhere. He had been pleased to sell out there and come ahead when Clay had told him he was going to take the place as marshal in Warlock; he had been eager to move on, eager for a change, but there was no change. It was the same, and he was only half done.

The batwing doors swung inward and Curley Burne and one of the Haggins came in. They did not see him, and he watched them go down along the bar, Curley Burne with his sombrero hanging against his back from the cord around his neck. They shouldered their way up to the bar, McQuown’s first lieutenant and McQuown’s cousin. And McQuown himself was coming in tonight, Dechine had said. He felt an anticipatory pleasure, and, almost, excitement.

He sat regarding the slight nervousness within himself as though it were some organic peculiarity, watching the heads turning covertly toward the newcomers and listening to the heavy conglomerate noise of men drinking, quarreling, whispering, gossiping, and to the little silences from the nearby layout when a card was turned and then the sudden click of chips and counters. The piano notes flickered through the noise like shards of bright glass. The sounds of money, he thought, and raised his glass again.

“Here’s to money,” he said, not quite aloud. After a time you discovered that it was all that was important, because with it you could buy liquor and food, clothes and women, and make more money. Then, after a further time, you went on to discover that liquor was unnecessary and food unimportant, that you had all the clothes you could use and had had all the women you wanted, and there was only money left. After which there was still another discovery to be made. He had made that by now, too.

Still, though, he thought, putting his glass down untouched and turning again to gaze at the two at the bar, there was a thing or two worth watching yet. The eyes that chanced to meet his in the mirrors behind the bar glanced away; they all disliked him already, as always, and he could enjoy that, and enjoy, too, their displeasure and surprise that Clay should associate with him, that Clay was his friend. There were a few tilings yet.

Basine had lowered the chandelier and was lighting the wicks with the long-handled spill. As each flame climbed and spread, the room lightened perceptibly. He noticed that the piano notes no longer filtered through the sounds around him; the professor was coming toward him, in his shiny black suit.

“Well, sir!” the professor said, sitting down opposite him. “Place should be filling up pretty soon now, shouldn’t it?” His eyes were like bright beads.

“Why, yes, sir, Professor. I believe it should.”

“Well, now, this place has done fine here, Mr. Morgan. I wouldn’t have believed it, coming in here cold like we did. Nice town too, but noisy.” He leaned forward, conspiratorially. “However, I see that a couple of McQuown’s people are in tonight. Expecting trouble, sir?”

“Always expect trouble, Professor,” he said, conspiratorially too. “That’s my practice.”

The professor cackled, but he seemed distressed. The professor leaned toward him again as he shuffled the cards once more and dealt them out for patience.

“I’ve been thinking, Mr. Morgan.”

“Now, why is that, Professor?”

“You know me, Mr. Morgan. I have worked for you for two years now, here and Fort James, and I’m an honest man. You know, I have to speak my mind when I see a thing that’s wrong. Well, sir, money is being wasted here. By you, Mr. Morgan, on me!”

The professor had spoken dramatically, but Morgan did not look up from his cards. “How is that, Professor?”

“Mr. Morgan, I am an honest, outspoken man, and I have to say it. No one can hear that piano going, with the runkus in here. It is a waste of money, sir, and I made up my mind I was just going to say it to you.”

“Play louder,” he said; now he saw, and was bored. Taliaferro, who owned the Lucky Dollar and the French Palace, had been after the professor again. He flipped the cards rapidly, red onto black, black onto red, the aces coming out one by one; cheating yourself, he thought, as the kings appeared, queen to king, and jack to queen, and ten to jack – what use to play it out? But he continued to turn and place the cards, cheat himself, and laugh at himself for it. The last day, he thought, would be the day when he could laugh at himself no longer.

The professor was staring at him with his face askew as though he were about to cry. “Why, I play as loud as I can, sir!” the professor said, in an aggrieved and trembling voice.

Morgan said, “Taliaferro?”

The professor licked his lips. “Well, sir, it is that fellow Wax that works for Mr. Taliaferro. You know that Mr. Taliaferro went and got a piano for the French Palace, but there is no one around can play one but me. Well, they have been after me, Mr. Morgan, and you know I wouldn’t leave working for you for double pay, but– Well, I was thinking, like I said, since it is a waste of your good money me playing here with nobody can hear it, so much runkus going on – I thought I might go up there to the French Palace and waste Mr. Taliaferro’s money.”

“You are too good to play a piano in a whorehouse, Professor,” he said, and sat staring steadily at the other until the professor left him and went slowly back over to the piano.

Morgan watched a man he had never seen before enter and move over to the faro layout to stand behind Matt Burbage. The newcomer wore dusty store pants and a dust– and sweat-stained shirt. He was not heeled, was thin, not quite tall, with a narrow, clean-shaven face and a prominent bent nose. He bent over to speak to Burbage, and straightened suddenly, his lips bent into a strained grin. As he turned away and moved toward the bar, somebody cried, “Hey, Bud!”

Haggin flung himself upon the newcomer, and Curley Burne came up to slap him on the back. “Why, Bud Gannon!” Burne said. One on either side of him, they dragged him to the bar.

Morgan watched the three of them in the mirror. He had heard that Billy Gannon had a brother off somewhere. A group of miners came in, in their wool hats and faded blue clothes and heavy boots, two of them sporting red sashes – heavy, pale, bearded men. It was difficult to tell one from the other among them, but they were trade. Clay appeared behind them in his black frock coat.

Clay held the batwing doors apart as he halted for a fraction of a second, and in that fraction glanced, without even appearing to turn his head, right and left with that blue, intense and comprehensive gaze. Then, removing his black hat, he came over and sat down on the far side of the table and placed his hat on the chair beside him. “Evening,” he said.

Morgan grinned. “Is, isn’t it? And a couple or three San Pablo boys over there at the bar, too.”

“Is that so?” Clay said, with interest. “McQuown?”

“He’s supposed to show tonight.”

“Is that so?” Clay said again. He stuck out his lower lip a little, raised his eyebrows a little. “Hadn’t heard. I guess I ought to be tending to business instead of buggy-riding around.”

Now the professor’s piano playing carried well enough. Morgan could see the eyes watching Clay in the mirror. Murch had shifted the shotgun slightly, so that the muzzle was directed toward the three at the bar.

“Been a hot day,” Clay said. He propped a boot up on the chair where he had laid his hat. Beneath the black broadcloth of his coat his shirt was wilted.

“Hot,” Morgan said, nodding. As he poured whisky into the second glass he watched Clay’s pursed, half-smiling mouth beneath the thick, blond crescent of mustache. “And it looks like a hot night,” he said.

Clay grinned crookedly at him and they raised their glasses together. “How?” Clay said.

“How,” he replied, and drank. “Look at them,” he said, and indicated the people in the Glass Slipper with a nod of his head. “They are all in a twitch. If they stay around they might see a man shot dead – you or one of McQuown’s. Only there might be stray lead slung and bad for their hides. But the money’s been paid and time for the show to begin. You like this town, Clay?”

“Why, it’s just a town,” Clay said, and shrugged.

“Just a town,” Morgan said, grinning again as Jack Cade came in. “Smaller than most and about as dull. Hotter than most, and dustier, but it has got a fine pack of bad men. Not just tourists like those Tejanosin Fort James, either.”

“Who’s that one?” Clay said thoughtfully, as Cade swung on down the bar, dark-faced with a stubble of beard, his round-crowned hat exactly centered on his head, his holstered Colt swung low.

“Jack Cade,” Morgan said; he had made it his business to know who McQuown’s people were. Cade joined the others at the bar, elbowing a miner out of the way. “Next to him is Curley Burne – number two to McQuown. That’ll be Billy Gannon’s brother in the store pants, and the other is one of the Haggin twins, cousins of McQuown’s. One’s right-handed and one left. This’s the left-handed one, but I forget his name.”

Clay nodded, watching them with a slight shine now in his blue eyes, a little more color showing in his cheeks. The room had quieted again, and there was traffic moving toward the door. The doctor and Burbage left the faro layout. As they went out they encountered another bunch of miners entering. “Doc,” each miner said, as he passed the doctor. “Doc.” “Evening, Doc.” “You’ll be needed later, I hear, Doc.”

Clay grinned again. Luke Friendly came in. With him was a cocky, mean-faced little man who swaggered like a sailor walking the deck in rough weather. They joined the others, where the little man turned to glance at Clay, and spat on the floor.

“I expect that might be Pony Benner, that shot the barber a while back,” Morgan said. “I haven’t seen him in before. The big one is Friendly. By name, not nature. But watch out for Cade. He is a bad one.”

“So I hear.”

“McQuown is sitting off to let you chew your fingernails up a while. He won’t play it your way, Clay. He will play it with a back-shooter, which is his style. Watch out for Cade.”

“Why, I will play it my own way, Morg. And see if they don’t have to, too.”

Morgan shrugged and raised his glass. “How?”

“How,” Clay said, nodding, and they drank.

“I hope you have got on your gold-handled pair. There will be a lot disappointed here if they don’t get to see them flash.”

He laughed, and Clay laughed too, easily. Clay said, “Why, they are for Sunday-go-to-meeting. This is a work day.”

Carl Schroeder was approaching, and Clay got politely to his feet. “Evening, Deputy,” he said, and put out his hand. Schroeder shook it, said, “Evening, Marshal,” nodded tightly to Morgan, and sat down, pushing his hat back on his head. Above the brown of his face his forehead was a moist, pasty white. Little muscles stood out along his jaw, like the heads of upholstery tacks.

“I will stick by tonight, Marshal,” Schroeder said, in a strained voice that was almost a stutter. “I am no shakes of a gunhand, but it’ll maybe help to have me by.”

“Why, I kind of thought I could count on you, Deputy,” Clay said. He paused a moment, frowning. “But when it comes right down to it, this is no trouble of yours. You are not paid for it and I am – no offense meant.”

“Pay is not the only reason for a thing, Marshal,” Schroeder said. He looked down, scrubbing his hands together as though they itched.

Clay said, “Morg, would you call for another glass, and—”

“No, not for me. No, thanks,” the deputy said. He looked sick with dread. His back was to the bar and he tried awkwardly to glance around, and then he said, “Is Johnny Gannon with them over there, can you see, Morgan?”

“He’s there,” Morgan said, and picked up the cards again. Schroeder bared his teeth in some kind of grimace. Clay got to his feet. His Colt was out of sight beneath the skirt of his black frock coat.

“Might take a little paseararound town, Deputy,” he said. “There is no reason to sit in here and give ourselves the nerves.” Schroeder scrambled up quickly, and Clay took up his hat.

“I’ll probably clean them out myself,” Morgan said, “if they get noisy.” Schroeder stared, and Clay grinned at him. Morgan watched them leave, taking a cigar from his breast pocket and clamping his teeth down on it. Schroeder kept close as a shadow to Clay’s heels.

As soon as they had gone, Murch signaled to Basine to replace him as lookout. Murch clambered ponderously down and came over toward Morgan. He looked like a carp, with his wall eye and his great slit of a mouth.

“Something going to come off in here?” Murch said, in his gravelly voice.

“Yes.”

“How you want to handle it?”

“Tell Basine I want him behind the bar. You on the stand. They’ll play one behind him. It’ll probably be Cade. You hold on whoever it is with the shotgun and let go if he moves.”

“Holy Jumping H. Jupiter!” Murch muttered. “I can’t let that thing off, it’s crowded in here! It’ll mash half the place full. I’ll—”

“You’ll let it off if one of them makes a move at Clay’s back,” he said, through his teeth. He stared into Murch’s straight-on eye. “I don’t care who you mash.”

Murch said, “All right,” unemotionally. The piano began to play again. Murch poured whisky into the glass Clay had left; his throat worked as he drank.

“What’s chewing the professor?” he asked.

“Taliaferro wants him to play that new piano at the French Palace. That Wax’s been scaring him.”

“That’s poor of Wax,” Murch said.

“He just works for Taliaferro, and Taliaferro’s got a new piano and nobody to run it.”

Murch nodded stolidly. “What’ll we do about it, Tom?”

“I’ll see,” Morgan said. “Get back up on that stand. I meant what I said about backshooters, Al.”

Murch nodded again. Sweat showed on his forehead in a delicate fringe beneath his receding hair. He went back over to the faro layout.

Morgan poured himself another quarter-inch of whisky, leaned back, and waited.

It was dark outside when McQuown came in, wearing a pale buckskin shirt, smiling pleasantly, his face slanted down and his red beard against his chest, the lamplight catching glints off the big silver conchos on his belt. With him were Billy Gannon and Calhoun. Billy looked like his brother, Morgan thought, except that he was six or eight years younger and had a sparse young mustache sprouting on his lip, and his nose was straight, his eyes narrower and warier. His walk was a copy of Curley Burne’s slow-gaited, cocky stride.

Morgan nodded to McQuown as the three of them went on down the bar. Billy yelled with surprise and jumped forward to embrace his brother, while McQuown glanced casually around the room. Now there was a steadier exodus. When McQuown’s eyes met his for a moment, Morgan grinned back. “All right, McQuown,” he whispered, hardly aloud. “Clay Blaisedell won’t play your game, but I can, and better than you.”

5. GANNON SEES A SHOWDOWNSTANDING beside his brother at the bar of the Glass Slipper, John Gannon looked from one to another around him – at Pony Benner’s mean, twisted little face; at Luke Friendly, who could, at least, be dismissed as a blowhard and braggart; at the sour, cruel, dark features of Jack Cade, whom he had always feared; at Calhoun, with whom he had learned to be merely careful, as with a rattlesnake out of striking distance; at Curley Burne, who, with Wash Haggin, had been his friend, whose droll, easy manner of speech he had once tried to copy, and whose easy gait he had seen that Billy was copying now. He looked at Abe McQuown’s keen, cold, red-bearded face. Once, when he had been Billy’s age, he had admired Abe more than he ever had any other man.

Now he was back among them, and he tried to smile at Billy, his brother. Billy looked thinner and taller in his double-breasted flannel shirt and his narrow-legged jeans pants. It was like seeing a photograph of himself taken five years ago – same height, same weight, the same quick, not quite sure movements that he recognized as having been his own, but surer than his own had been; the same narrow, intent, deep-eyed face, with the only differences the mustache Billy was trying to grow, and Billy’s nose straight still, whereas his own slanted off to one side, broken-bridged and ugly. Billy was watching Abe McQuown.

“Blaisedell’ll be about halfway to Bright’s by now,” Pony said, in his shrill voice, and Luke Friendly laughed and glanced toward the batwing doors.

“Don’t you wish it, Shorty,” Wash Haggin said, and winked at Gannon. He had a big mustache, whereas his twin was – or had been – cleanshaven, silent, and reserved. Chet was home, Wash had said, disgustedly, when Gannon had asked.

“Blaisedell’ll be around,” Wash went on, to Pony. “This one is a different breed of horse.”

Abe smiled and bent his head forward as he lit a cheroot. In the brightness of the match flame, his skin looked clear and fine as oiled parchment. Long, harshly cut wrinkles ran down his cheeks into his beard. He shook the match out, blew smoke, glanced up to meet Gannon’s gaze, and smiled again.

“It is surely nice to see you back, Bud,” he said. His eyes were bright as wet green stones. Casually he turned his buckskin back, and Cade leaned forward to whisper to him. Abe nodded in reply.

Gannon saw the big, flat-faced lookout staring down at them. “What’s going on?” he said to Billy.

“New marshal,” Billy said. “Clay Blaisedell, that’s a gunman from Fort James. Citizens’ Committee hired him to run us out of town. We’ll see who’s going to run tonight.”

“Well, I expect he won’t run,” Wash said cheerfully. “He’s the one that shot Big Ben Nicholson,” he told Gannon. “And got a pair of gold-handled Colts from some Wild West writer for it.”

Gannon nodded, watching Billy’s stony young profile. “Pretty bad odds against him, isn’t it?” he said, more drily than he intended.

Billy’s face turned sullen. “Why, we’ll make a play in here,” he said.

“Not so bad odds in here,” Wash explained. He jerked a thumb and whispered, “Morgan over there is kin to him, I heard; anyway they are partners here. And a charge of buckshot up there,” he went on, indicating the lookout. “Only I hope to God it is birdshot. And count up Morgan’s dealers and barkeeps and who knows what the hell else besides. Morgan is supposed to’ve cut plenty score himself. It is a fair enough shake.”

Cade finished his conversation with Abe and turned to the bar with his back to the others. Calhoun was watching the door, scraping a thumbnail along his boneless nose.

“Billy,” Abe said. “Maybe you and me and Curley and Wash could have a hand of cards over there.”

Billy nodded tautly, and, with Wash and Curley, moved off after Abe. As they sat down in the rear, beyond the piano, a group of miners hurriedly vacated a nearby table. The piano player banged his hands down in a sour chord, and got up too, bumping, in his departure, against Calhoun and Friendly as they moved down to the end of the bar, and apologizing profusely. Pony Benner swaggered over toward the lookout’s stand. Men were crowding out the door.

Gannon felt leaden as he stood alone against the bar, watching, in the mirror, McQuown’s disposition of his men. At the table Billy sat facing the bar, with Abe and Wash on either side of him, Curley across from him, back to the room. So it would be Billy. He remembered that his father, dying, had charged him with watching out for Billy until Billy was grown. But Billy had grown too fast for him, and already Deputy Jim Brown was dead by Billy’s six-shooter. His responsibility had been long ago dissolved in incapacity, and now the dread he felt as he stared into the mirror was more disgust and hopelessness than fear. He had fled this hard and aimless callousness where a human life was only a part of a game, and never, so far as he had seen, a fair game. He had thought he could escape it by fleeing it. But he could not escape having been one of McQuown’s, nor the nightmare-crowded memory of what they had done, himself as much as any of them, one day six months ago, in Rattlesnake Canyon just over the border; and he could not escape himself.

The Glass Slipper continued to empty, men abandoning the bar and the gambling layouts without apparent haste, but steadily, clotting together as they thrust their way out the doors. The gambler, Morgan, came down along the bar against the traffic, his hair gleaming smoothly silver under the light of the chandelier, his face dead pale with the black bar of the mustache across it. Icy eyes touched his briefly. Morgan disappeared through the door at the back, beyond where Calhoun and Friendly stood.

Then Gannon was aware of the congealing silence. He saw the men crowded at the louvre doors pushing back out of someone’s way. Among them appeared a man in black broadcloth, wearing a black hat. A step behind him was Carl Schroeder.

Carl halted there, among the others, but the man who must be Blaisedell came on, a tall, broad man with long arms, and a way of carrying himself that was halfway between proud and arrogant. His faintly smiling mouth was framed between a thick, fair curve of mustache and a prominent, rounded chin. For an instant the most intensely blue eyes Gannon had ever seen glanced directly into his. The marshal halted at a vacant stretch of bar between him and Jack Cade, who was bent forward over his glass.

“Whisky,” the marshal said. A reluctant barkeep brought it. The sound as he set the bottle down on the bar was very loud, as was the slap of a coin on wood. The bartender, his hands in his apron, glided rapidly backward. Then there was no sound at all.

In the mirror Gannon saw that Curley Burne had risen and turned, and was standing to the right of McQuown, facing the room now. So it was not to be Billy; but he felt no relief.

Curley was grinning. Glints of light flickered in his black curls. Billy and Wash were sitting with their hands on the table before them. McQuown shuffled the deck of cards with a sound like tearing cloth.

“Oh, Mister Marshal!” Curley said.

Out of the corners of his eyes Gannon watched the marshal raise his glass to his lips and toss down the whisky. Then he set the glass down, and turned.

Curley’s face wore a mock sheepish expression. “Marshal,” Curley said. “I wonder could I make a little complaint?”

Blaisedell inclined his head once, politely.

“I guess it is up to me, Marshal,” Curley went on. “There is a lot of complaint around about it – but folks have just kind of gone and left it up to me. Those gold-handles of yours, Marshal. They are awful hard on a fellow’s eyes.”

Someone laughed shrilly.

The door through which Morgan had disappeared stood open now, and Morgan leaned there casually.

“I mean, speaking for myself now, Marshal,” Curley said. “I would surely hate to get a case of eyestrain from those gold-handles. They are so bright in the sun and all. A fellow is not much use without his good eyes. I hear they have been strained bad in Warlock lately.”

“You could close your eyes,” Blaisedell said, in his deep voice, but pleasantly still.

With a deprecating gesture Curley said, “Aw, Marshal. I’d just be bumping and wumping all over the place, trying to get around with my eyes closed. And look foolish! Marshal, por favor, couldn’t you just not polish them handles so bright, hand-rubbing on them like they say you do?”

“Why, I guess I could do that. If things fell right in town here.”

Curley nodded seriously, but long dimples cut his cheeks. Blaisedell stood with his boots set apart, his arms hanging loosely. Beyond him Gannon saw Jack Cade’s head half turned, his lips drawn tight and bloodless over his teeth. Carl Schroeder stood alone just inside the batwing doors; he looked as though he were in pain.

“Marshal,” Curley said loudly. “What if somebody painted them handles black for you?”

“It might do,” Blaisedell said. He walked forward, not directly toward Curley, but at a slant to the right, and Gannon knew the marshal had not moved until he had worked out the geometry involved. Gannon found himself sidling doorward along the bar. He stepped past Jack Cade, but Cade’s hand caught his arm and held him there, between Jack and the lookout on the stand. He stared up into the lookout’s sweating face and the round huge muzzle of the shotgun.

“But who is to do it?” Blaisedell said. He moved another step toward Curley.

Gannon felt the movement of Cade’s arm behind him. Instinctively he jerked his elbow back, and slammed his hand down on Cade’s Colt, gasping as the sharp point of the hammer tore into the web of flesh between his thumb and forefinger, and staring up at the shotgun barrel. He fought the Colt down, looking wildly toward the table now, and saw, past Blaisedell’s broad back, Curley’s hand snatch for his six-shooter; and saw the swifter flick of the bottom of Blaisedell’s coat. Curley’s hand halted, the gleaming barrel of his Colt not quite level, and his left hand held spread-fingered and protective before his belly. His face was twisted into a grimace that was half grin still, half shock and horror as he stared at Blaisedell’s hand, which was hidden from Gannon. In that same frozen instant McQuown flinched forward away from Curley, Wash straightened stiffly, and Billy sat perfectly still with his hands held six inches above the table top. Gannon saw him glance to his right, where Morgan had produced a short-barreled shotgun, which he held trained on Calhoun and Friendly. Then, as Gannon turned back to face the lookout again, he had a glimpse, behind and below the stand, of Pony Benner’s baffled, furious face gaping at Blaisedell.

“Whooooo-eee!” he heard Curley whisper. Jack Cade’s breath was scalding on the back of his neck. The upward pressure on the gun beneath his hand was released, the hammer drew loose from his flesh. He saw Blaisedell make a peremptory motion with his head at Curley.

Curley gave his hand a little shake and his Colt fell with a thump shockingly loud. Blaisedell returned his own piece to the holster hidden by the skirt of his coat. It was not gold-handled, Gannon saw.

He felt blood sticky and warm in the palm of his hand; he pressed it hard against his pants leg, his back to Cade still. Sweat stung in his eyes, and above him he saw sweat dripping from the lookout’s chin. The muzzle of the shotgun was drawn back a little. Glancing toward the door he saw that Carl Schroeder had disappeared.

“McQuown,” Blaisedell said. McQuown sat in profile, his head bent forward, deep shadows caught in the lines in his cheeks. He acted as though he had not heard. “McQuown,” Blaisedell said, again.

Billy’s hot eyes swung toward his chief, and Abe McQuown slowly pushed his chair back and rose. He slowly turned, one hand braced on the back of his chair, his eyes moving jerkily from side to side, his nostrils flaring and slackening with his breathing. His beard twitched as though he were trying to smile. Morgan was leaning casually in the doorway again, the short-barreled shotgun under his arm.

“McQuown,” Blaisedell said, for the third time. Then he said, his deep voice without expression, “My name is Blaisedell and I am marshal here. I am hired to keep the peace here,” he said, and stopped, and waited, just long enough for McQuown to speak if he wished, but not so long that he had to.

Then Blaisedell glanced around as though he were talking to all now, in the breathless silence. “Since there is no law for this town I will have to keep the peace as best I can. And as fair as I can. But there is two things I am going to lay down right now and back up all the way. The first one is this.” His voice took on an edge. “Any man that starts a shooting scrape in a place where there is others around to get hurt by it, I will kill him unless he kills me first.”