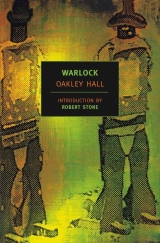

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

April 10, 1881

IT IS impossible to watch these things happening and feel nothing. Each of us is involved to some degree, inwardly or outwardly. Nerves are scraped raw by courses of events, passions are aroused and rearoused in partisanships that, even in myself, transcend rationality.

It must be a wracking experience to stand before a mob as Schroeder and Gannon did last night; to do it not once, but twice, and to be trampled at the last by men no more than crazed beasts. I write this trying to understand Carl Schroeder, as well as in memoriam to him. I see now that his office had served to ennoble him, as it had done with Canning before him. We gave him not enough credit while he lived, and I think we did not because he was too much one of us. God bless his soul; he deserves some small and humble bit of heaven, which is all he would have asked for himself.

He was an equable and friendly man. Perhaps he was inadequate to his position here. Yet who would have been wholly adequate except, perhaps, Blaisedell himself? I think a part of Schroeder’s increasing strength (has it not been a part of all our increasing strength?) was Blaisedell’s presence and example here. I think he must have been badly shaken by Blaisedell’s decline from Grace. As he drew his strength from Blaisedell, so must he have been all too rawly aware of the cruel vicissitudes of error, or rumored error, or of mere foul lies, to which such dispensers of rough-and-ready law as Blaisedell, and himself, were prey.

Poor Schroeder, to die not only in an undignified street scrape, but in one of the multitudinous arguments over Blaisedell and McQuown. Buck Slavin heard the quarrel, and saw it at the end; he says it seems to him that Carl was as much at fault in it as Curley Burne. He says there was a deeper grudge there than the mere quarrel, but I think of my own feelings of that time last night, and know it would have taken little to rouse me to a deadly rage.

Buck was present at the General Peach almost until Schroeder’s death, and says that Schroeder chided himself bitterly for being tricked with what is called the “road agent’s spin.” This is a device whereby the pistol is proffered butt foremost, and then spun rapidly upon the trigger finger and discharged when the muzzle is level. It is a foul trick. Curley Burne has had more friends in this town by far than any other creature of McQuown’s. He has only sworn enemies now.

Gannon did not accompany the posse that went out after Burne, perhaps, as Buck suggests, because Curley has been an especial friend of his, or perhaps, as the doctor says, because Carl expressed a wish that Gannon remain with him in his final hour. The miners set fire to the Glass Slipper shortly after Schroeder’s death and Gannon has been much occupied in putting out the fire. The feeling is that he was too much occupied with it, and that his proper business lay with the posse. It is to be hoped that his office will be as ennobling to Gannon as it has been to his last two predecessors.

I think that Carl Schroeder would have been pleased to know that his death has taken men’s minds away from Blaisedell’s failure before the jail, and concentrated hate upon one man. I fervently hope that the posse will catch Curley Burne and hang him to the nearest tree.

I burn the midnight oil, I bleed myself upon this page in inky blots and scratchings. How can I know men’s hearts without knowing my own? I peel back the layers one by one, like an onion, and find only more layers, smaller and meaner each than the last. What dissemblers we are, how we seek to conceal from our innermost beings our motives, to call the meanest of them virtue, to label that which in another we can plainly see as devilish, in ourselves angelic, what in another is greed, in ourselves righteousness, etc. Observe. The Glass Slipper is burned, gutted to char and stink, and the pharmacy beside it saved by a miracle. The fire was set by the miners; they have got back at Morgan. They are devils, I say, to so endanger a town as tinder-dry as this. But is that it? No, they have endangered my property. I will forgive being shamed, discountenanced, and insulted; threaten my property and I will never forgive. Take everything from me but my money. With money I can buy back what I need, the rest is worthless.

Poor devils, I suppose they had to destroy something. Men rise to the heights of courage and ingenuity when they avenge their slights or frustrations. It has always been so. It is comforting to some to see men work together with a good will against catastrophe. Humanity at its best, they say. Yet against, as I have written. When will humanity work with all its strength, its courage and ingenuity, and all its heart, for?

Morgan is burnt out. Will he rebuild, or accept this as earnest of the widespread sentiment against him here and depart our valley of Concord and Happiness? And in that case what of Blaisedell, who has been banking faro for him? Will he go too, or will he undertake the position of Marshal here again? I am sure the Citizens’ Committee intends to ask, or beg, him to reassume his office, next time it meets.

Blaisedell and Morgan: it is said that Blaisedell did not shoot his assailants before the jail because he would not kill for the sake of Morgan, who had wrongfully murdered Brunk (if not a number of others!). Yet Blaisedell’s prestige would have been even more grievously damaged had Morgan actually been taken out and hanged, and so I see Miss Jessie’s part in this. Blaisedell is obviously very much her concern, and, with the friendship of Blaisedell and Morgan an established fact, did she not realize that Morgan had to be saved at all costs, distasteful as the object of her salvage must have been to her?

There has been some talk to the effect that Blaisedell began his career as a gunman in a position similar to that of the now-departed Murch, as pistolero-in-chief for Morgan’s gambling hall in Fort James, and that he killed at Morgan’s behest various and sundry whom Morgan found bothersome in his affairs of the heart, as well as in his business. Morgan once saved Blaisedell’s life, it is further said, so Blaisedell is sworn to protect Morgan forever and serve whatever purpose Morgan assigns him. Morgan becomes possessed of horns, trident, a spiky tail, and Blaisedell’s soul locked up in a pillbox.

Morgan is replacing McQuown as general scapegoat and what might be called whipping-devil. McQuown has remained in San Pablo and out of our ken for so long that he is becoming only a name, like Espirato, and someone readier to hand is needed. So are the witches burned, like coal, to warm us.

April 11, 1881

The posse has returned with Curley Burne, and Deputy Gannon has shown his true colors.

Burne has gone free on Gannon’s oath that Schroeder’s death-bed words were that his shooting was accidental, caused by his pulling on the barrel of Burne’s six-shooter and thus forcing Burne’s finger against the trigger. Judge Holloway, whatever his feelings in the matter, could not under these circumstances remand Burne to Bright’s City for proper trial; there would be no point in it with Gannon prepared to swear such a thing. Joe Kennon, who was at the hearing, says he thought Pike Skinner would shoot Gannon then and there, and called him a liar to his face.

It is fortunate for Gannon that this town has had a bellyful of lynch gangs lately, or he and Burne would hang together tonight. Oh, damnable! Gannon must have been eager indeed to please McQuown, for in all probability Burne would have been discharged by the Bright’s City court, as is their pleasure. Certainly Gannon is in danger here now, and, if he is here to serve McQuown in any way he can, has destroyed any further usefulness he might have had to the San Pabloite by this infuriating, and, it would seem, foolish, action. It is presumed that he will sneak out of town at the first opportunity, and that will be the last Warlock will see of him. Good riddance!

The posse was evidently divided to begin with as to whether they should capture Curley Burne at all, a number of them feeling he should be shot down on sight. His horse had gone lame, however, and, lucidly for him, he offered no resistance. Opportunities were evidently made for him to try to escape, so ley fugacould be practiced, but Burne craftily did not attempt to take advantage of them. No doubt he was already counting on Gannon’s aid.

It must have taken a strange, perverted sort of courage for Gannon to stand up with such a brazen lie before so partisan a group as there was at Burne’s hearing. Evidently he tried to claim that Miss Jessie had also heard Schroeder’s last words. Several men promptly ran to ask her if this was so, but she only increased Gannon’s shame by replying, in her gentle way, that she had been unable to hear what Schroeder was saying at the end, since his voice had become inaudible to her. Buck says now that he knew all the time that Gannon was trying to play both ends, and was just biding his time to pull one coup for McQuown such as this. I must say I cannot myself view Gannon as a villain, but only as a contemptible fool.

Burne has promptly and sensibly made himself scarce. Some say he has joined the Regulators, who are encamped at the Medusa mine. If Blaisedell will resume his duties as Marshall here, and this town has its say, Curley Burne will become his most urgent project.

Toward this end the Citizens’ Committee is meeting tomorrow morning, at the bank.

April 12, 1881

Blaisedell has resumed his position, and Curley Burne has been posted from Warlock. I have never felt the temper of this place in such a unanimously cruel mood. It is fervently hoped that Curley Burne, wherever he is, will take the posting process as what we have never before considered it to be – a summons, instead of a dismissal.

April 13, 1881

Word seems to have come, I’m sure I don’t know how – perhaps it is some kind of emanation in the air – that Burne will come in. It seems to me that at one moment there was not a man in Warlock who believed he could be fool enough to come, and at the next it was somehow fixed and certain that he would. He is expected at sun-up tomorrow, but I still cannot believe that he will come.

April 14, 1881

I saw it, not an hour ago, and I will put down exactly what I saw. I will then have this record so that, in time to come, if what others perceived is changed by their passions or the years, I may look back at this and remind myself.

Before sun-up I was on the roof of my store, sitting behind the parapet. Others came up a ladder placed against the Southend Street wall, made apologetic gestures to me for invading my premises, and squatted silently near me in the first gray light. There were men to be seen in the street, too, occupying doorways and windows, and a number of them established within the burnt-out shell of the Glass Slipper. From time to time whispering could be heard, and there were frequent coughs and a continual rustle of movement, as in a theater when the curtain is about to rise.

Some of our eyes were trained east, for the sun, or for Blaisedell, who would presumably appear from the direction of the General Peach; some west, as the proper direction for Curley Burne’s entry upon the stage.

There came the rhythmic creaking of wheels; it was the wagons taking the miners out to the Thetis, the Pig’s Eye, and the farther mines, ten or twelve of them, with the miners seated in them knee to knee. Their bearded faces glanced from side to side as the wagons passed down Main Street, with, from time to time, a hand raised in greeting to a fellow, but none of the cheerful, disgruntled, or profane calling back and forth we are so used to hearing of a work-day morning. The water wagon, driven by Peter Bacon, crossed Main Street on its morning journey to the river. It was seen that the harness of the mules glittered, and all eyes turned to see the sun.

It climbed visibly over the Bucksaws, a huge sun, not that which Bonaparte saw through the mists of Austerlitz, but the sun of Warlock. I felt its warmth half gratefully, half reluctantly. There was an increasing stirring and rustling in the street. I saw Tom Morgan come out of the hotel, and, cigar between his teeth, seat himself upon the veranda. He leaned back in his rocking chair and stretched, for all the world as though it were a bore but he would make the best of what poor entertainment Warlock had to offer. I saw Buck Slavin with Taliaferro in the upstairs window of the Lucky Dollar, Will Hart in the doorway of the gunshop, Gannon leaning in the doorway of the jail, a part of the shadow there, appearing as tiredly and patiently permanent as though he had spent the night in that position, in that place.

“Blaisedell.” Someone said it quite loudly, or else many whispered it in chorus. Blaisedell debouched from Grant Street into Main. He waited there a moment, almost uncertainly, with his shadow lying long and narrow before him. He wore black broadcloth with white linen, a string tie; beneath his open coat the broad buckle of his belt was visible, his weapons were not. With almost a twinge of fear I watched him start forward. He carried his arms most casually at his sides, walked slowly but with long, steady strides. Dust plumed about his feet and whitened his boots and his trouser bottoms. Morgan nodded to him as he passed, but I saw no answering nod.

“He’ll just have a little walk and then we’ll go home,” someone near me whispered.

Blaisedell crossed the intersection of Broadway, and from all around I heard a concerted sigh of relief. Perhaps I sighed myself, with the surety that Curley Burne was not going to appear after all. Hate can burn itself out in the first light of day as readily as love can. I could see Blaisedell’s face now very clearly, his broad mouth framed in the curve of his mustache, one of his eyebrows cocked up almost humorously, as though he, too, felt he would only have a little walk and then go home.

The sun had separated itself from the peaks of the Bucksaws by now; it glinted brilliantly upon the brass kick-plate on the hotel door. I saw Morgan, slouched in his rocking chair, raise his hand to take the cheroot from his mouth, then hold cigar and hand arrested. He leaned forward intently, and I heard a swift intake of breath from all around me, and knew that Curley Burne had appeared. I was reluctant to turn and see that this was so.

He was a hundred yards or so down Main Street. I saw Gannon, without changing his position, turn with that same slow reluctance I had felt in myself, to watch him. I found in myself, too, a grudging admiration for Burne, that he managed even now to accomplish that saunter of his we in Warlock knew so well. His shoulders were thrown back at a jaunty angle, his sombrero hung, familiarly, down his back, his flannel shirt was unbuttoned halfway to his cartridge belt as though in contempt of the morning chill, his striped pants were thrust into his boot tops. He looked very much a Cowboy. He was grinning, but even from where I was I could see his struggle to maintain that grin; it was exhausting to see it. I had to remind myself that he had murdered Carl Schroeder by a filthy trick, that he was a rustler, road agent, henchman of McQuown’s. “Dirty son of a b–!” growled one of my companions, and summed up what I had to feel, then, for Curley Burne.

He and Blaisedell were not a block apart when there was another gasp around me, as Burne broke stride. He halted, and cried out, “I have got as much right to walk this street as you, Blaisedell!” I felt ashamed for him, and, all at once, pity. Blaisedell did not stop. I saw Burne raise a hand to his shirt and wrench it open further, so that his chest and belly were exposed.

“What color?” he cried out. “What color is it?” He glanced up and around at us, the watchers, with quick, proud movements of his head. The skull-like grin never left his face. Then he started forward toward Blaisedell again. He sauntered no longer, and his hand was poised above the butt of his six-shooter. My eyes were held in awful fascination to that hand, knowing that Blaisedell would give him first draw.

It flashed down, incredibly swift; his six-shooter spat flame and smoke and my ears were shocked by the blast despite my anticipation of it – three shots in such rapid succession they were almost one report, and Burne and his weapon were obscured in smoke. Blaisedell’s own hand seemed very slow, in its turn. He fired only once.

Burne was flung back into the dust and did not move again. He had a depthless look as he lay there, as though he were now only a facsimile of himself laid like a painted cloth upon the uneven surface of the street. Blood stained his bare chest, his right arm was flung out, his smoking Colt still in his hand.

Blaisedell turned away, and as he retraced his steps I watched that marble face for – what? Some sign, I do not even know what. I saw his cheek twitch convulsively, I noticed that he had to thrust twice for his holster before he was able to reseat his Colt there. I could not see whether it was gold-handled or not.

The doctor appeared in the street, to walk through the dust to where Burne lay, carrying his black bag. A short, stocky, bowed figure in his black suit, he looked sad and weary. Gannon did not move from his position in the jail doorway. His eyes, from where I watched, looked like burnt holes in his head. Other men were coming out along the far boardwalk, and there was no longer silence.

“Center-shotted the b– as neat as you please,” a man near me said, as he got to his feet and spat tobacco juice over the parapet.

“Give him three shots,” said another. “Couldn’t give a man any more than that. I call that fair.”

“Give him all the time in the world,” agreed a third.

But I could feel in their voices what I myself felt, and feel more strongly now. For all that Blaisedell had given Burne three shots, for all he had given him all the time in the world, we knew we had not witnessed a gunfight but an execution. I leaned upon the parapet and looked down upon the men who had surrounded the mortal remains of Curley Burne, and I saw, when one of them moved aside, a little patch of bloody flesh. I thought of that gesture he had made, opening his shirt and confronting us with the color of his belly; showing us, more than Blaisedell.

It had been an execution, and at our order. Perhaps we had changed our mind at the last moment, but there was no reprieve, no way, before the end, to turn our thumbs up instead of down, and save the gladiator. And I think we felt cheated. There should have been some catharsis, for Carl Schroeder had been avenged, and an evil man had received his just deserts. There was no catharsis, there was only revulsion and each man afraid, suddenly, to look into the face of the one next to him. And there was the realization that Curley Burne had not been an evil man, the remembrance that we had once, all of us, liked and enjoyed him to some degree; and there was the cancerous suspicion spreading among us that Gannon might not, after all, have been lying.

I feel drained by an over-violent purge to my emotions, that has taken from me part of my manhood, or my humanity. I feel scraped raw in some inner and most precious part. The earth is an ugly place, senseless, brutal, cruel, and ruthlessly bent only upon the destruction of men’s souls. The God of the Old Testament rules a world not worth His trouble, and He is more violent, more jealous, more terrible with the years. We are only those poor, bare, forked animals Lear saw upon his dismal heath, in pursuit of death, pursued by death.

I am ashamed not only of this execution I myself have in part ordered, but of being a man. I think the climax to my shame for all of us came when Blaisedell was walking back up the street, dragging his arrow-thin, arrow-long shadow behind him, and Morgan came down from the veranda of the Western Star to put a hand on his shoulder, no doubt to congratulate his friend. At that moment I heard someone near me on my rooftop whisper – I did not see who, but if I believed in devils I would have been sure it was the voice of one come to yet more hideously corrupt our souls than we have ourselves corrupted them this day – whisper, “There is the dirty dog he ought to kill.”