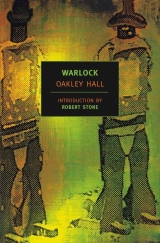

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 33 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

He gaped at her. She sounded as though he had promised to play the organ at her wedding and did not know how, but would learn, for her. He laughed out loud and she looked momentarily confused. But then she gathered up her skirts and ran out of the corral and through the pelting rain toward the back steps of the General Peach. She ran as a young girl runs, lightly but awkwardly.

He put on his hat and went out into the rain, and his cigar sizzled and died. The rain beat viciously down on his hat and back from an oyster-colored sky. It made craters in the dust where it fell, and muddy puddles spread in the ruts. He walked back to the Western Star Hotel in the rain.

57. JOURNALS OF HENRY HOLMES GOODPASTURE

June 3, 1881

IT HAS been most oppressively hot this last week or ten days, as though the sun were burning each day a little closer to the earth. Then this afternoon it rained, a brief and heavy downpour that turned the streets to mud. By tomorrow the mud will be gone, and the dust as fine and dry as ever. Yet we will have a spring: here there is a miniature spring of green leaves and blossoms appearing after any rain. This should cheer us, for all have been tense, or listless.

Six weeks have passed since Whiteside made his promise to us. Buck feels we should set out immediately to put our threats into effect, but I have instead written a strong letter to Whiteside saying that in one more week we will do so. I am sure my further threats are worthless, but it allows me to procrastinate. Hart, more honest than I, readily admits he has no stomach for another journey to Bright’s City.

The Sister Fan has had to put on a night crew. The water struck there at the lower levels has become a problem of increasing dimensions. They have a fifty-gallon bucket to bail out the excess and men must be kept working night and day to stay abreast of the flow. God-bold, the superintendent, says it looks as though expensive pumping machinery will have to be brought in. The Medusa strikers are, the doctor says, in despair over this (as they were previously over a rumor that Mexicans were to be brought in to work the idle Medusa), feeling that the Porphyrion and Western Mining Co. will not attempt to settle the strike until it is seen how grave is the water problem at the Sister Fan.

All is quiet in the valley. The Cowboys, now apparently led by Cade and Whitby, have, according to report, descended into Mexico on a rustling and pillaging expedition. This is looked upon as foolhardy at the present time, since the border is supposedly under close surveillance.

It is whispered that a board cross appeared briefly upon McQuown’s grave, with the inscription “murdered by Morgan.” In a way, I think, people have come to fear Morgan as they once feared McQuown. It is an unreasonable thing, and I suppose it is closely akin to the passions aroused in a lynch mob. Somehow he stands convicted of the murder of McQuown, and other murders as well, by some purblind emotionality for which there seems little basis in fact.

There is talk of bad blood between Gannon and Blaisedell, this stemming, evidently, from the encounter they had when the miner who shot MacDonald took refuge, himself wounded, in the General Peach. No one seems to know what actually passed between them, but I have found from long experience that much smoke can be generated here from no fire at all. The human animal is set apart from other beasts by his infinite capacity for creating fictions.

I must say that I myself have felt it necessary to change my own opinions of the deputy to a degree. I feel he is an honorable, though slow-moving man – a plodder. He has taken on a certain stature here – proof of which lies in the pudding of the speculation and of contention regarding him. He has become what none of the other deputies here has ever been – except possibly, and briefly, for Canning – a man to reckon with.

MacDonald is in Bright’s City. I suspect he will soon return, and I suspect that he is plotting reprisal. He is indeed hot-headed enough to seek illegal means of punishing the strikers, who I am sure he feels conspired to take his life by means of a hired assassin. If he is fool enough, however, to attempt to convene his erstwhile Regulators again to this purpose, he will find an angry town solidly aligned against him. MacDonald has no friends in Warlock.

So life in Warlock, with terrors more shadows at play upon the wall than actuality. The atmosphere remains a charged one, yet I wonder if it is not merely something that will go on and on without ever breaking into violence; if it is not, indeed, merely part of the atmosphere of Warlock, with the dust and heat—

I spoke too soon. Another drought is ended. A gunshot; I think from the Lucky Dollar.

June 4, 1881

It is uncertain yet what provoked the shooting last night in the Lucky Dollar. Will Hart, who was present, says that Morgan suddenly accused Taliaferro of cheating, and, in an instant, had swung around and shot a half-breed gunman named Haskins through the head, and swung back evidently with every intention of shooting Taliaferro, who, instead of drawing his own pistol, sought to flee, and, on his hands and knees, was crawling to safety through the legs of the onlookers. Morgan, instead of pursuing him, had immediately to face the lookout, who had brought his shotgun to bear. All this, says Hart, took place in an instant, and Morgan was cursing wildly at Taliaferro for his flight and calling upon the lookout to drop his weapon, which order the lookout had the courage to ignore, or more probably, Hart says, was too paralyzed to comply with. The situation remained in this deadlock while Taliaferro made good his escape, and until Blaisedell, who had previously been present but had absented himself for a stroll along Main Street, burst back in.

Blaisedell immediately commanded Morgan to drop his six-shooter, although, Hart says, Blaisedell did not draw his own. Morgan refused and abused Blaisedell in vile terms. Blaisedell then leaped upon his erstwhile friend and wrested his weapon from him, upon which, Morgan, evidently surprised by Blaisedell’s quick action and further infuriated by it, closed with the Marshal and a violent brawl ensued. Evidently Morgan sought to cripple Blaisedell a dozen times by some villainous trick or blow, but Blaisedell at last sent him sprawling senseless to the floor, and then carted him off for deposit in the jail as though he had been any drunken troublemaker.

Last night the town was in part aghast, in part wildly jubilant, and the rumor sprang up immediate and full-blown that Blaisedell had posted Morgan out of town – people here are apt to forget that it is the Citizens’ Committee who posts the unworthy, not Blaisedell himself. The judge, however, was promptly summoned to hear Morgan on the murder of Haskins. Morgan claimed he had caught Taliaferro using a stacked deck. This is a strange argument. No doubt it is true, but in these engagements between master gamblers, such as the one that has been in progress for some time between Taliaferro and Morgan, it is clear to all that stacked decks are being used and the whole basis of the game becomes Taliaferro’s cunning in arranging a deck against Morgan’s cunning at ferreting out the system used. It has been said that Morgan was surpassingly clever at guessing Taliaferro’s machinations previous to this, but that for the last two days he has been losing heavily. Morgan also claimed that Haskins had, as Taliaferro’s gunman, attempted to shoot him in the back. Will says he could not have known this without eyes in the back of his head, but Morgan’s statement in this regard was supported by Fred Wheeler and Ed Secord, who swore that Haskins had indeed drawn his six-shooter as soon as Morgan had accused Taliaferro of cheating, and showed every sign of aiming a shot at Morgan. The judge could do nothing but absolve Morgan for the death of Haskins, and although Morgan had clearly been bent upon Taliaferro’s speedy demise, he had been thwarted in this, and was culpable of nothing by our standards of justice, except creating a disturbance, for which he was given a night in jail.

Gannon seems to have arrived in the Lucky Dollar while Morgan and Blaisedell were seeking to maim each other, but was fittingly nonparticipant throughout. I think it can be said of him that he knows his place.

The hearing over, members of the Citizens’ Committee met stealthily to discuss the situation, and to remind ourselves that on the occasion of Blaisedell’s first encounter with McQuown and Burne, Blaisedell had warned the outlaws in violent terms against starting gunplay in a crowded place, where there was danger to innocent bystanders; the parallel was clear. Still in cowardly secrecy, a general meeting was called at Kennon’s livery stable. The secrecy was necessitated by the fact that we were not sure what Blaisedell’s attitude toward his friend now was, but we were one and all determined to seize the occasion at its flood and post Morgan out of Warlock, if possible. All were present except for Taliaferro, who was not sought, and the doctor and Miss Jessie, who, it was felt, would make us uncomfortable in our plotting.

It was speedily and unanimously decided that Morgan should be posted. His actions had constituted, we told ourselves, exactly the sort of threat and menace to the public safety with which the white affidavit was meant to deal. The problem lay only in advising Blaisedell of our decision. It might suit him exactly, some felt, while others were afraid it would not suit him at all. Still, there are members of the Citizens’ Committee, whose names I shall not mention here, who, in the past weeks and even months, have become restive over Blaisedell’s high salary, or wish him gone for other reasons. They now began to speak up, each giving another courage, or so it seemed – I will not say more about them than that Pike Skinner had to be forcibly restrained from striking one of the more outspoken. Their attitude in general was that if Blaisedell refused to honor our instructions to post Morgan out, as he had done in the case of the miner Brunk, then he should resign his post. In the end their view carried, and I am sorry to say that I, in all conscience, felt I had to agree with them. Blaisedell is our instrument. If he will not accept our authority, then he must not accept our money.

The meeting was adjourned, to be reconvened this morning with Blaisedell instructed to attend. He came, much bruised around the face, but he was not told he was to post Morgan out of Warlock. It was he who did the speaking. He said he was resigning his position. He thanked us gravely for the confidence we had previously reposed in him, said that he hoped his fulfillment of his duties had been satisfactory, and left us.

Warlock, since this morning, has been as silent as was the Citizens’ Committee when we heard his statement. I think I am, ashamedly, as disappointed as the rest, but I know I think better of Blaisedell than I have ever before. It was clear that he knew exactly what was our intention at the meeting, and, since he did not wish to do it, saw that he must resign. There was no reproach evident in his demeanor. We will reproach ourselves, however, for what was said of him the night before. And I respect him for not wishing to post his friend from Warlock; I think he has acted with honor and with dignity, and I have cause to wonder now if this town, and the Citizens’ Committee, has ever been worthy of the former Marshal of Warlock.

58. GANNON SPEAKS OF LOVE

GANNON lay fully clothed on his bed and contemplated the darkness that enclosed him, the barely visible square of vertical planes that were the walls marred here and there by huddled hanging bunches of his clothing, and the high ceiling that was not visible at all, so that the column of darkness beneath which he lay sprawled seemed topless and infinitely soaring. He had been forced out of the jail tonight not by any danger, but only because there were too many people there endlessly and repetitiously talking about Morgan and Blaisedell, Blaisedell and Morgan, and he did not want to hear any more of it.

Yet even now he could hear the excited murmur of voices from one of the rooms down the hall, and he knew that throughout Warlock it was the same, everyone talking it over and over and over, changing and fitting and rearranging it to suit themselves, or rather making it into something they could accept, angrily or puzzledly or sadly. Each time they would come to the conclusion that Blaisedell had better move on, but, having reached that conclusion, they would only start over again. He, the deputy, he thought, must not enter their minds at all; nor could he see in the black blank of his own mind what his part was. He had come, finally, almost to accept what Morgan had said to him – that it was not his business.

He heard the upward creaking of the stairs, and then Birch’s high voice: “Now watch your step, ma’am. It is kind of dark here on these steps.”

He started up, and groped his way to the table. His hand encountered the glass shade of the lamp; he caught it as it fell. He lit a match and the darkness retreated a little from the sulphur’s flame, retreated farther as the bright wedge mounted from the wick. As he replaced the chimney there was a knock. “Deputy!” Birch said.

He opened the door. Kate stood there in the thick shadows; he could smell the violet water she wore. “Here is Miss Dollar to see you,” Birch said, in an oily voice.

“Come in,” he said, and Kate entered. Birch faded into the darkness, and the steps creaked downward. The voices in the room down the hall were still. Kate closed the door and glanced around; at his cartridge belt hanging like a snakeskin from the peg beside the door, at the clothes hanging on their nails, at the pine table and chair and the cot with its sagging springs. Lamplight glowed in a warm streak upon her cheek. “Sit down, Kate,” he said.

She moved toward the chair, but instead of seating herself she put her hands on the back and leaned there. He saw her looking around a second time, with her chin lifted and her face as impassive as an Indian’s. “This is where you live,” she said finally.

“It isn’t much.”

She did not speak again for a long time, and he backed up and sat down on the edge of the bed. She turned a little to watch him; one side of her face was rosy from the lamp and the other half in shadow, so that it looked like only half a face. “I’m leaving tomorrow,” she said.

“You are?” he said numbly. “Why – why are you, Kate?”

“There is nothing here for me.”

He didn’t know what she meant, but he nodded. He felt relief and pain in equal portions as he watched her face, which he thought very beautiful with the light giving life to it. He had never known what she was, but he had known she was not for him. He had dreamed of her, but he had not even known how to do that; his dreams of her had just been a continuation of the sweet, vapid day and night dreams embodied once in Myra Burbage, not so much because Myra had been attractive to him as because she was the only girl there was near at hand; knowing then, as he knew now, that there would be no woman for him. He was too ugly, too poor, and there were too few women ever to reach down the list of unmarried men to his name.

“You’re going with Morgan?” he asked.

Her face looked suddenly angry, but her voice was not. “No, not Morgan. Or anybody.”

He almost asked her about Buck, but he had once and she had acted as though he were stupid. “By yourself?” he asked.

“By myself.”

She said that, too, as though it should mean something. But he felt numb. What had been said was only words, but now the realization of the actuality of her leaving came over him, and he began to grasp at the remembrance of those times he had seen her, as though he must hold them preciously to him so that they would not disappear with her. He had, he thought, the key to remember her by.

“When?” he said.

“Tomorrow or – Tomorrow.”

He nodded again, as though it were nothing. He could hear the roomers talking down the hall again. He rubbed his bandaged hand upon his thigh and nodded, and felt again, more intensely than he had ever felt it, his ineptness, his inadequacy, his incapacity with the words which should be spoken.

“I guess I didn’t expect anything,” Kate said harshly. “I guess you are sulking with the rest tonight.”

“Sulking?”

“About Blaisedell,” she said, and went on before he could speak. “I was the only one that thought it was wonderful to see,” she said in a bitter voice. “For I saw Tom Morgan try to do a decent thing. I think it must have been the first decent thing he had ever tried to do, and did it like he was doing a dirty trick. And had it fall apart on him. Because Blaisedell was too—” Her voice caught. “Too—” she said, and shook her head, and did not go on. Then she said, as though she were trying to hit him, “I’m sorry you feel cheated.”

“You think if Blaisedell had posted him he would have gone?”

“Of course he would have gone. He was trying to give Blaisedell that – so people would think Blaisedell had scared him out. I think it’s funny,” she said, but she did not sound as though she did.

They were talking about Blaisedell and Morgan like everyone else, and he knew she did not want to, and he did not want to.

He looked down at his hands in his lap and said, “I’d thought you might be going with Morgan.”

“Why?”

“Well, I talked to him. He said you’d been his girl but that you were through with each other. But I thought you might have—”

“ Itold you I’d been his girl,” Kate said. Then she said, “Did he tell you more? I told you more, too. I told you what I’d been.”

He closed his eyes; the darkness behind his eyes ached.

“I guess I am still,” her voice continued. “Though I don’t have to work at it any more, since I’ve got money. That came from men.” Again she spoke as though she were hitting him. She said, “I’m damned if I am ashamed of it. It is honest work and kills no one. What are you waiting for, a little country girl virgin?”

Now he tried to shake his head.

“Why, men marry whores,” she said. “Even here. But not you. And not me. There is nothing here at all for me, is there?” Her voice began to shake and he looked up at her and tried to speak, but she rushed on. “So I have been a whore by trade,” she said. “But I can love, and I can hate by nature. But you can’t. You just sit and stare in at yourself and worry everything every way so there is no time nor place for any of that. Is there?”

“Kate,” he said in a voice he could hardly recognize. “That is not so. You know well enough I have loved—”

“Don’t say that!” she broke in fiercely. Her face looked very red in the lamplight, and her black eyes glittered. “I have never heard you lie before and don’t start for me. I know you haven’t been to the French Palace,” she said, “because I asked.” She said it cruelly. “I wanted to know if you were waiting for a little country virgin or not. And I—”

“That’s not so, Kate!” he cried in anguish.

Slowly the lines of her face relaxed until it was as gentle and full of pity as that of the little madonna in her room. He had never seen it this way before. “No,” she said gently. “No, I guess it isn’t. I guess you thought going to a whore wasn’t right. And I guess you thought that about me, too.”

“Kate – I guess I knew you felt – kindly toward me. I kind of presumed you did. I’m not a fool. But Kate—” he said, and couldn’t go on.

“But Kate?” she said.

“Well, this is where I live.”

He waited for a long time, but she did not speak. When he looked up he saw the harsh lines around her mouth again. He heard the rustle of her garments as she moved; she clasped her hands before her, staring down at him, her eyes in shadow.

“Another thing,” he said. “You have been in the jail and seen those names scratched on the wall there.” He took a deep breath. “There was something Carl used to say,” he went on. “That there wasn’t a man with his name on there that didn’t either run or get killed. And Carl used to say who was he to think he was any different? And that he wouldn’t run. I think he even knew who was going to kill him.”

“I’ve got money, Deputy,” Kate said. “Do you want to come with me? Deputy, this town is going to die and there is no reason for anybody to die with it. I am asking you to take the stage to Bright’s City with me tomorrow. Out of here, out of the territory.”

“Kate—” he groaned.

“Do you want to, or not?”

“Yes, but Kate – I can’t, now.”

“Killed or run!” she cried. “Deputy, you can run with me. I have got six thousand dollars in the bank in Denver. We can—” She stopped, and her face twisted in anger and contempt, or grief. “What kind of a fool am I?” she said, more quietly. “To beg you. Deputy, you can’t give me anything I haven’t had a thousand times and better. I can give you what you’ve never had. But you will lie down and die instead. Do you want to die more?”

“I don’t want to die at all. I only have to stay here.” He beat his bandaged hand upon his knee. “Anyway till there is a proper sheriff down here, and all that.”

“Why?” she cried at him “Why? To show you are a man? I can show you you are more a man than that.”

“No.” He got to his feet; he rubbed his sweating hands on his jeans. “No, Kate, a man is not just a man that way. I—”

“Because you killed a Mexican once,” she broke in. Her tear-shining eyes were fastened to him. “Is that why?”

“No, not that either any more. Kate, I have set out to do a thing.” He did not know how to say it any better. “Well, I guess I have been lucky. That’s part of it, surely. But I have made something of the deputy in this town, and I can’t leave it go back down again. Not till things are – better. I didn’t drop it a while back when I was afraid, and, Kate, I can’t now because I would rather go off with you”—he groped helplessly for a phrase—“than anything else in the world.”

He wet his dry lips. “Maybe to you Warlock is not worth anything. But it is, and I am deputy here and it is something I am proud of. There are things to do here yet that I think I can do. Kate, I can’t quit till it is done.”

He saw her nod once, her face caught halfway between cruel contempt and pity. He moved toward her and put out a hand to touch her.

“Don’t touch me!” she said. “I am tired of dead men!” She stepped to the door and jerked it open. The bottom of her skirt flipped around the door as she disappeared, pulling it half closed behind her.

He took up the lamp and followed her, stopping in the hallway and holding the lamp high to give her a little light as she hurried down the stairs away from him, and, when she was gone, stared steadily at the faces that peered out at him from the other doorways until the faces were drawn back and the doors closed to leave him alone.