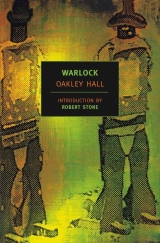

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“Stop it!”

“All right, I will stop it. And you get out of here. You are not a man. Not the man I want.”

“More man than you are woman, I guess, Miss Dollar.” He spoke in anger; instantly he was sorry. “I am sorry,” he said quickly. “I didn’t go to say a thing like that. I’ll ask you to forgive me, Kate.”

But she didn’t speak, and he could feel the hate. It was as though he were in a cage with an animal. He turned and moved toward the door.

He heard a shot. It came from the direction of Main Street, and there was a yell, and a chorus of yells. But still he did not leave. “Kate—” he said.

“Maybe they have killed him for me,” Kate said, viciously, and he went outside. He ran down toward the corner of Main Street with his ribs aching and the scabbarded Colt slapping against his leg.

It was some time before he could find out what had happened; no one seemed to know. Someone said that Blaisedell had shot Curley Burne, who had been taken dying to the General Peach; another thought that some of the Regulators had come in and scared up a Medusa miner. He crossed the street finally, to another group of men before the Billiard Parlor. Hutchinson, Foss, and Kennon were there.

“Carl got shot,” Foss told him. “It was Curley.”

“Dirty hound!” Kennon said, in a cracked voice.

“Where is he?”

“Forked a horse and lit out running,” someone said. “There is a bunch going to take out after him. They’re down at—”

“No– Carl!” he said.

“They took him over to the General Peach,” Hutchinson said. “He was bleeding bad.”

As Gannon ran back down Main Street, Kennon shouted after him, “You had better start getting a posse together, Gannon!”

There was another bunch before the General Peach, and a number of horses. “It’s Gannon,” someone said. “Here comes Johnny Gannon.” He made his way through them and up the steps, where Miss Jessie’s man Tittle barred his way with a Winchester.

“Listen, nobody else comes—”

He shouldered past, and Tittle stumbled back clumsily, banging his rifle butt against the door. “Where is he?” Gannon panted, starting back toward the hospital room. Then he saw Pike Skinner and Mosbie through Miss Jessie’s open door. Buck Slavin was there, and Sam Brown and Fred Wheeler. Morgan leaned on the foot of the bed, with the doctor beside him, and Blaisedell stood apart. Miss Jessie was sitting beside the bed, where Carl was.

“Well, hello, Johnny,” Carl said, in a breathless voice. He looked like a scared, white-faced boy with a pasted-on, graying mustache. Gannon hadn’t realized how gray Carl was. He moved over to kneel beside the bed, next to Miss Jessie’s chair. Carl wet his lips and carefully turned his head toward him.

“You will have to deputy alone awhile, Johnny.”

“Sure,” he panted. “Surely, Carl. We’ll make out.”

Behind him Pike Skinner said roughly, “We will help him till you are up and around again, Carl.”

Carl grinned thinly; he turned his head a little farther toward Gannon, and winked. “Sure,” he whispered. “There is some good boys to help. They have been rallying round. You’ll be all right, Johnny.”

“Hush, now, Carl,” Miss Jessie said, and patted his hand. She wore the high-necked, frilled blouse with the black necktie she had worn when she had come to the jail, and she smelled cleanly of sachet and starched linen. “You mustn’t talk so much, Carl,” she said.

“it’s all right,” the doctor said, in his clipped, curt voice.

“I have always been a talker, ma’am,” Carl said. “It is hard to quit being one now.”

Leaning on the brass foot of the bed in a clean shirt and trousers, his cigar bobbing in the corner of his mouth as he spoke, Morgan said gently, “A man needs a little rest after fighting those wild-eyed jacks off my neck half the night.”

Carl grinned again. Behind Morgan, Blaisedell stood with his arms folded over his chest, and only his blue eyes alive in his cold, bruised and scraped face. There was a tramp of hoofs outside the window, and Gannon could hear the men talking there. “Let’s get moving,” one said. “Where’s Gannon. He going to weasel on this?”

“What happened?” Gannon said quickly, to Carl.

“Just stupid,” Carl said, in an embarrassed voice. “Curley and me had some more words. That was there by the Billiard Parlor and I kind of surprised myself and him too getting drawed before he did.” He laughed shakily. “Durned if I didn’t! Well, I kind of cooled off, seeing I’d got the drop; so I thought I’d camp him in jail for the night. So I called for his piece—” His voice trailed off.

“Curley went to let him take it and then spun it on him,” Mosbie said. “I saw him do it, and a good lot of others standing there saw it. Run the road-agent spin on him, by God – pardon me, Miss Jessie. I should have chose him myself, I just about did earlier.”

“We’ll see he is caught, Carl,” Buck Slavin said solemnly.

Gannon saw a little cluster of bluish veins at Carl’s temple, and the slow beat of blood in them. He had never seen those veins there before. The flesh of Carl’s face looked as though it had been waxed.

“Better get a posse riding, Johnny,” Pike said. “There is a good lot gathered outside already.”

“Not much use till morning,” Carl said. “If I was doing it I’d wait. Nobody could follow sign till light.”

Miss Jessie patted Carl’s hand. Her hand was white and small beneath the long cuff of her sleeve, the nails cut shorter than Kate’s. Carl’s brows knit together beneath the long, crusted scratch on his forehead, and Carl’s eyes took on an inward expression.

“Feels like something’s broke loose again, Doc,” Carl said easily. “I don’t want to bleed up Miss Jessie’s nice bed.”

“It will stop,” the doctor said.

“Let’s go on outside,” Pike whispered, and he left the room, followed by Buck, Wheeler, Mosbie, and Sam Brown.

Gannon could hear more horses in the street now. He saw Carl’s eyes close and he quickly looked up at the doctor, who had on his nightshirt beneath his rusty black suit. The doctor shook his head.

Gannon saw that Blaisedell was watching him expressionlessly. Above Blaisedell’s head was a mezzotint of a man thrashing at some ocean waves with a long sword.

Carl opened his eyes again. “You know?” he said. “It makes a person sort of mad – I mean I was just watching it go by in my head here. Say you catch him, Johnny, and the judge binds him over to trial in Bright’s. He will just get off.” He laughed a little and said, “Are you going to post him out of town for me, Marshal?”

Gannon heard Miss Jessie draw in her breath; he saw Morgan’s face harden. Blaisedell didn’t give any sign that he had heard.

Miss Jessie said, “David, I think he ought to rest a little now. I think everybody ought to leave and let him rest.” She said it as though she were talking to the doctor, but it sounded like a command. Gannon started to get to his feet.

“Except Johnny,” Carl said. “Leave Johnny stay.”

Miss Jessie rose with a quick movement, brushing her hands together in her skirt. Her eyes looked tired, but very bright; her brown ringlets swung as she turned toward Blaisedell. She went over to take Blaisedell’s arm, as though she must lead him out, and Morgan’s cold eyes followed her all the way. They all left the room.

Gannon knelt uncomfortably beside the bed, watching Carl’s face, in profile to him, and the steady throb of the little cluster of veins. Carl whispered, “I’m going, old horse.”

Gannon shook his head.

“It is like big gray curtains coming down. You can kind of see them trailing down – like the bottom of a tornado cloud coming down. Getting black like that too, but slow.”

“I’m sorry, Carl,” he said.

“Surely,” Carl said, as though to comfort him. “We have been friends and got along, haven’t we? I was a good enough deputy, wasn’t I? Whatever old Judge had to say about it.”

Gannon tried to speak and choked on it.

Carl laughed soundlessly. “Well, I don’t know what I am crying about now. I knew one of those cowboys was going to score me, and I guess I’d just as soon it was Curley.

“Ah, I came in all big medicine brave on account of Bill Canning,” he went on. “And saw what I was into, and caved in for a while. Pure fright. But I come up again, I’ll say that for myself. I picked up there toward the last. Why, I was right proud of myself standing up to Curley like I did. I just wish I didn’t have to go out on killing that poor, stupid jack, though; that was no kind of thing. And sorry to leave you right in the middle of all hell, Johnny. With Curley to get, and I suppose somebody ought to get word in to Bright’s City on Murch, in case he went that way. And muckers and Regulators.” He began to chuckle again, his shirt trembling over his chest with it. “Maybe I picked the best time after all,” he said. “But damn Curley Burne anyhow.”

Carl looked exhausted now, and his eyes seemed suddenly sunken. After a moment he said, “Me and Curley scrapped over Blaisedell mostly. I guess you figured that.”

“I thought it’d been that, Carl.”

Carl’s eyes flared in their sockets, like candles guttering. “Once in a while – once in a long while there’s a man– Blaisedell made a man of me, Johnny. But now—”

“I know,” he said quickly.

“Things getting him down,” Carl whispered. “Bringing him low. Like those jacks tonight, and nothing for a man to do to help him back. Then somebody comes along and you can speak up for him. And maybe because it is the only thing you can do – you push it too hard. Maybe I pushed Curley too hard.”

“Never mind it now, Carl.” Gannon could hear now, in the street outside, the pad of hoofs and the jingle of spurs and harness, and voices, diminishing as the men rode away.

“I always was a talker,” Carl said. His eyes drooped closed. His hands moved slowly to fold themselves upon his chest. He looked as though he were aging at tremendous speed.

Gannon rose from his knees and sank into the chair. He saw Miss Jessie standing in the doorway behind him, one hand to her throat and her round eyes fixed on him steadily.

Carl whispered something and he had to bend forward to hear it.

“—post him out,” Carl was saying, smiling a little, his eyes still closed. “And right down the middle of the street with no two ways about it, like that in the Acme was.” His voice came more strongly. “Why, that’d be epitaph enough for a man! Carl Schroeder that was deputy in Warlock, shot by Curley Burne. And right next to me: Curley Burne, killed for it by Clay Blaisedell, Marshal. Cut that in stone! That’d be—” His words became a kind of soft rustling Gannon could no longer understand.

Gannon sat watching with fascination the slow movement in the little veins, knowing he should be both with the posse, which was not a posse without him, and here with Carl.

“That stupid jack!” Carl said suddenly. His eyes opened and all at once fright was written with cruel marks upon his face. He reached for Gannon’s hand and gripped it tightly. “Johnny! Bring out your Colt’s and hand it here!”

“Carl, you—”

“Quick! There is not much time!”

Gannon drew his six-shooter and held it out where Carl could see it, which seemed to be what Carl wanted.

“Hold it right,” Carl said. “Finger on the trigger.” Carl caught hold of the barrel and gave it a jerk. Then he groaned. “Yes!” he whispered, as Gannon withdrew the Colt. “I pulled on it the same as that damned, stupid jack did to me with the shotgun. No, not the same!But by God it was!”

Carl turned his head from side to side with a tortured movement. “Oh, God Almighty, there is no way to know! But maybe he didn’t go to do it, Johnny.”

“But he ran—” he started.

“Because there was half a dozen there would’ve cut him down! Johnny—” Carl stopped, his throat working as though he could not swallow. Finally he got his breath; he lay there panting. “Forgive as you would be forgiven,” he whispered. “And I will be going to that judgment seat directly. Oh, God!” he whispered, dully.

Tears squeezed from beneath his eyelids. His throat worked again. He whispered, “Johnny – I guess you had better tell them that Curley didn’t go to do it.”

That was all. Still a faint flicker of life showed in the blue veins. Gannon stared at them, slowly thrusting the muzzle of his Colt toward its scabbard, until the barrel finally slid in; he sat hunched and aching, watching the little veins, and at no given instant could he have said that the movement in them ceased. There was only, after a time, the realization that Carl’s life was gone, and he rose and disengaged the counterpane from beneath Carl’s arms, folded the hands together on the thin chest, and drew the counterpane up over all.

He backed away, upsetting the chair in his clumsiness, and catching it as it fell. Jessie Marlow still stood in the doorway. She nodded, just as he said, “He’s gone,” and raised her finger to her lips in a curious, straitened, intense gesture he did not understand.

He moved out past her into the dark entryway. Blaisedell stood across from him, his legs apart, hands behind his back, his head bent down – as still as a statue. Morgan sat on the bottom step, smoking.

“He’s gone,” he said again. Still Blaisedell didn’t move. The doctor came out of the shadows near the front door and followed Miss Jessie into her room. Gannon knew these out here had not heard Carl’s last words; he wondered if even Miss Jessie had.

“They went on down toward San Pablo,” Morgan told him. “Skinner said he thought you would just as soon not go anyway.”

He nodded dumbly, and went on outside. There was no one now in the street before the General Peach. He walked to the jail and in the darkness there sank down in the chair at the table, with his head in his hands. He did not know if he could face telling them what Carl had said. They would say he lied, with utter condemnation and contempt, and the lie thrown in his face until he would have to fight back. But how would he be able to blame them for thinking that he lied? He could only pray that the posse would not catch Curley. Surely they would not catch Curley Burne.

He groaned. Finally he rose, with broken glass scraping beneath his boots, and lit the lamp, staring, in the gathering light, at the names scratched on the wall. He slid open the table drawer and took out Carl’s pencil. With his ribs aching, he squatted before the list of the deputies of Warlock, and, carefully, in small, neat lettering, he added, beneath Carl’s name, the name of John Gannon.

35. CURLEY BURNE LOSES HIS MOUTH ORGAN

CURLEY was half asleep in the saddle when the sun came up, sudden and painfully bright just above the peaks of the Bucksaws. As he cut in from the river his eyes felt sandy and his spine jarred into the shape of a buttonhook. The gelding he had taken plodded along, stiff-legged, and he was grimacing now at every jolt.

“That is some gait you got, horse,” he complained, leaning both hands on the pommel to ease his seat. “I never heard of a horse without knee joints before.” He reached for his mouth organ inside his shirt; somehow the cord had got broken, and he had to dig for the mouth organ inside his shell belt. He blew into it to wake himself up, and now he began to feel a growing elation. For now he could go, now he must move on, and there was good news for Abe about Blaisedell’s comedown for him to leave on.

The elation faded when he thought of Carl Schroeder. Carl had been an aggravating man, and more and more aggravating and scratchy lately, but he had not wanted to see Carl dead. He wondered if there was a posse out yet, and he looked back for dust; he could see none.

“Poor old Carl,” he said aloud. “Damned scratchy old son of a bitch.” In his mind’s eye he saw Carl go down with the front of his pants afire, and he winced at the sight. He knew that Carl was dead by now.

The gelding went grunting pole-legged down a draw, and labored up the rise beyond it. He had a glimpse of the windmill on the pump house with the blades wheeling slowly in the sun, and the tall chimney of the old house. He pricked the gelding’s flanks with his spurs. “Let’s run in there with our peckers up, you!” The gelding maintained the same pace. “Gait like banging an ax handle on a fence post,” he said.

By dint of jabbing in his spurs, yelling, and flapping his hat right and left, he got the gelding into a shambling, wheezing run down the last slope. He fired his Colt into the air and whooped. The gelding fell back into a trot. Joe Lacey and the breed came out of the bunkhouse and waved to him. Abe appeared on the porch of the ranch house in an old hat and a flannel shirt, and no pants on. The legs of his long-handled underwear were dirty and baggy at the knees.

Curley gave one last half-hearted whoop and jumped off the gelding; his knees gave beneath his weight and he almost fell. Abe leaned on the porch rail, sleepy and cross-looking, as Curley mounted the steps.

“Where’d you get that bottlehead?”

“Stole him, and a bad deal too.” He leaned against the porch rail beside Abe. “I’m leaving, Abe,” he said. “Things look like they’ll be getting hot for me here.”

Abe said incuriously, “Blaisedell?”

“Carl and me come to it.”

A shadow came down over Abe’s red-bearded face, and he blew out his breath in a whisper like a snake hissing.

“Abe!” the old man called from inside. “Abe, who is that rode in? Is that you, Curley?”

“It surely is,” he called back. “Coming and going, Dad McQuown. I’m on the run.”

“Killed him?” Abe said sharply.

“Looked like it. I didn’t stay to see.” When he flipped his hat off, the jerk of the cord against his throat made his heart pump sickly.

“Killed who?” Dad McQuown cried. “Son, bring me out so’s I can see Curley, will you? Killed who, Curley?”

“Carl,” Curley said. He tried to grin at Abe. He said loudly, for the old man’s benefit, “Run the road-agent spin on him. Neat!”

The old man’s laughter grated on him insupportably, and Abe cried, “Shut up, Daddy!” One of Abe’s eyes was slitted now, while the other was wide; he looked as though he were sighting down a Winchester. Curley saw Joe Lacey coming toward the porch.

“You are not needed here!” Abe snapped, and Joe quickly retreated. “What happened?” Abe said.

“Why, it seems like they get a new set of laws up there every time a man comes in. Now you can’t even talk any more. And scratchy! Well, I was there by Sam Brown’s billiard place, minding my own business and talking to some boys, and Carl comes butting in and didn’t like what I was saying. We cussed back and forth some, and—”

“God damn you!” Abe whispered.

Curley stiffened, his hands clenching on the rail on either side of him as he stared back at Abe.

“You did it now,” Abe said. He didn’t sound angry any more, only washed-up and bitter.

“What’s the matter, Abe?”

Abe shrugged and scratched at his leg in the dirty longjohns. “Where you going?” he asked.

“I guess up toward Welltown, and then– quién sabe?”

“In a hurry?”

“I don’t expect they got a posse off till sun-up. But it’s not something I better count on. Why’d you get so mad, Abe?”

“People liked Carl,” Abe said. He hit his fist, without force, down on the porch rail, and shook his head as though there were nothing that was any use. “They’ll hang this on me too,” he went on. “That I put you to killing Carl. But you’ll be gone. It’s nothing to you.”

“Ah, for Christ’s sake, Abe!”

“They have got me again,” Abe said.

“Sonny, you shut that crazy talk!” the old man shrilled. “Now, you bring me out there with you boys. Abe!”

“I’ll get him,” Curley said. He went inside to where the old man lay, on his pallet on the floor by the stove, and picked him up pallet and all. The old man clung to his neck, breathing hard. He didn’t weigh over a hundred pounds any more, and the smell of him was the hardest part of carrying him.

“Got the deputy, did you, Curley?” the old man said, blinking and scowling in the sun as Curley put the pallet down on the porch. “Well, now; I always thought high of you, Curley Burne!” His mouth was red and wet through his white beard. “Well now,” he went on, glancing sideways at Abe. “That’s all there is to it. Man’s pushing on you, all you do is ride in there—”

“By God, you talk,” Abe said, in a strained voice. “Daddy, I’ve told you I don’t mind dying, if that’s what you want of me. I just mind dying a damned fool!”

“Abe,” Curley said. “I guess I had better be moving.”

Abe didn’t even hear him. “I mind dying a damned fool, and I mind dying one for every man to spit on,” he went on. He began to laugh, shrilly. “Pile everything on me! By God, they will have a torchlight parade and fireworks when I am dead! They will carry him around Warlock on their shoulders and make speeches and set off giant powder, for him; that never did a sin in his life. And tramp me in the dust for the dogs to chew on – that never did anything else but!”

The old man gazed at his son in horror, at Curley in shame. There was an iron clamor from Cookie’s triangle, and the dogs began to bark out by the cook shack.

“Well, there is breakfast now,” the old man said in a soothing voice. “You boys’ll feel better after some chuck.”

“Blaisedell don’t stand so high now, Abe,” Curley said. “I heard a thing or two about Blaisedell, and saw a pack of miners tramp over him too.” He told about the miners storming over Blaisedell to try to lynch Morgan. Abe looked barely interested.

“And maybe things’re getting stacked against him some, for a change,” Curley went on. “There is plenty talk it was Morgan stopped that stage, and maybe Blaisedell with him.”

“That’s stupid,” Abe said, but he stood a little straighter.

“And that those boys was killed in the Acme Corral to cover it over.”

“That’s a stupid lie,” Abe said. He grinned a little.

“No, there is something there. Pony and Cal stopped that stage, surely. But you remember Cal and Pony being kind of suspicious back and forth about who it was shot that passenger, and then they finally decided it must’ve been Hutchinson trying to sneak a shot at Cal and the passenger jumped out and got hit instead. But maybe it wasn’t Hutchinson, either.”

Abe was nervously running his fingers through his beard.

“There is something there,” Curley said again. “Taliaferro had some news might interest you, and it is spreading around Warlock pretty good, I hear. There is some whore named Violet at the French Palace that was in Fort James when Morgan and Blaisedell was. And this Kate Dollar woman that Bud Gannon is chasing after now. Lew says this Violet says the Dollar woman was Morgan’s sweetie in Fort James, and she took up with another fellow and Morgan paid Blaisedell money to burn him dead. How a lot of people knew about it in Fort James– Wait a minute, now!” he said, as Abe started to interrupt. “And then this Dollar woman was married to the passenger that got shot on that stage. Now if Pony or Cal didn’t shoot him, who did? Lew likes it it was Morgan – he is down on Morgan something fierce – but there is talk that if Blaisedell hired out to Morgan for that kind of job once, why not twice? There is all kind of things being said around Warlock, Abe.”

“Boys, what is this hen-scratch low gossip you are talking here?” the old man said indignantly.

“Shut up,” Abe said, but he began to grin again.

He had better go, Curley thought. There was more than he had told Abe, but he did not like to hear himself saying all this. Lew Taliaferro was a man he could stand only if the wind was right; and what Taliaferro had told him, part of which he had just repeated to Abe, had made as poor hearing as telling, medicine though it was to Abe.

“So I expect you will be going into Warlock one of these days yourself,” he said, and tried to grin back at Abe’s grin. “There is a time coming. I wish I could go in with you when you go, but you won’t need me, Abe.”

“By God!” the old man whispered.

“I’d sure like to stay to see it,” Curley went on. “But it has come time for me to make tracks. Like you said, people liked old Carl.” He took a deep breath. “I’m telling you things are running the other way, Abe. You have done right, staying down here till they started changing. And it was the smartest thing you ever did, too, telling MacDonald you wouldn’t have nothing to do with his Regulators. Just wait it out. It won’t be long. Abe, Blaisedell is starting to come down like a pile of bricks.”

He felt exhausted watching the life and sharpness coming back into Abe’s face. He had given Abe what he had to give, and he would do it again, but he had lied when he had said he wished he could see the end. He could stomach no more of it.

“Thanks, Curley,” Abe said, softly. “You’ve been a friend.” With a lithe swing of his body he turned to gaze off at the mountains. His face, in profile, looked younger. He said, “Well, you will hear one way or other when the time comes.”

“I’ll drink a bottle of whisky to you, Abe.”

“Do that for me. One way or the other.”

“One way,” Curley said, grinning falsely.

“You have sure bucked him like a dose of kerosene,” the old man said, in a breathless voice. The clanging of the iron triangle sounded again.

“Better eat before you go,” Abe said.

“I’ll grab something and say so long to the boys.”

“What do you want to move on for, Curley?” the old man complained. “How’ll we make out? Have to break in a new hand on that mouth organ of yours.”

“You’ll never get one as good as me.”

“Wait a minute till I get my pants on,” Abe said, and disappeared inside.

Curley took the mouth organ out of his shirt and began to play the old man a tune. “Curley,” Dad McQuown said, scrounging up on one elbow. “Tell me how it was you popped that deputy before you go. Ran him the road-agent spin, did you?”

It was sour music he was making. He wiped the spit from the mouth organ, and put it down on the rail beside him. “No, it wasn’t that,” he said.

“You said—”

“It wasn’t so,” he said. “The whole thing was poor all around. He had the drop on me and I went to give him my Colt’s like a good boy. But he grabbed hold of the barrel—” He stopped, for Abe was standing in the doorway with his hands frozen where he’d been buckling his shell belt on. Abe’s eyes were blazing.

“You always was a God-damned liar, Curley Burne,” the old man said disgustedly, and lay back again.

“You didn’t mean to do it?” Abe whispered, and his face was crafty and cruel as Curley had not seen it since Abe had heard the Hacienda Puerto vaqueros were coming after them through Rattlesnake Canyon.

He shook his head.

“Carl went and did it himself? Pulling on the barrel with your finger on the trigger. Like that?”

“That was it.” The expression on Abe’s face frightened him a little, but then it was gone and Abe bent to attend to buckling his belt on. “It was poor,” Curley said. “It don’t set so good either, but it is done. I kind of thought I’d better not stick around and try and explain it to folks, what with five or six of them getting ready to pop away at me. Well, I guess I’ll go get some breakfast.”

Abe nodded. “I’ll go down and saddle up for you,” he said, in a strange voice. “You send the breed around and I’ll put him on that you rode out here on, and send him on down Rattlesnake Canyon in case they have got somebody following sign. You head for Welltown and I’ll get a herd run over your track.” Abe nodded again, to himself.

“Well, that’s fine of you, Abe.”

“So long, Curley,” the old man said. “You take care of yourself, hear?”

Curley hurried down the steps. “So long, Dad McQuown!” he called back over his shoulder. At the cook shack he shook hands around with the boys who hadn’t gone with MacDonald, and told them to say so long for him to the rest when they got back from Warlock. He sent the breed to Abe, and got some bread and bacon and a canteen of water from Cookie. Hurrying, he went on out to the horse corral, where Abe had saddled a long-legged, big-barreled, steady-standing gray he had not seen before. “He’ll take you in a hurry,” Abe said, and slapped the gray on the shoulder. Curley swung into the saddle, and Abe reached up to wring his hand.

“Curley,” he said.

“So long, boy, Suerte.”

“ Suerte,” Abe said, grinning, but not quite meeting his eyes. Something had gone wrong again, but now Curley was only in a hurry to get out. He swung the big gray out of the corral on the hard-packed red earth. He could see the dust the breed was making, heading south. The big gray moved powerfully; he drew up as Abe yelled something after him, and cupped a hand to his ear.

“I say!” Abe yelled. “They catch you all you do is see you get to Bright’s City for trial all in one piece. No worry then!”

Curley waved and spurred on again. When he had crossed the river that was the border of the ranch, he had never felt so free. He reached for his mouth organ. But he had left it on the porch rail.

His mood was not affected; he began to sing to himself. The gray loped steadily along. The land stretched board-flat away to Welltown, the gray-brown desert marbled with brush. The sun burned higher in the sky. He glanced back from time to time – at first he thought it was only a dust-devil.

Then he whistled. “We had better stop loafing, boy,” he said. “Look at them come!” But he was not worried, for the big gray was strong and fresh, and the posse must have been riding hard from Warlock. The gray broke into a long, swinging stride that ate up the ground, and he laughed to see the dust cloud fading behind him.

Then the gray grunted and went lame.

He dismounted to examine the hoof; carefully he looked over the leg for something wrong, but he could see nothing. The gray stood with the lame leg held off the ground, looking at him with unconcerned brown eyes. “Boy, why would you do such a thing?” he complained, and remounted and dug his spurs in. The gray limped along, grunting, more and more slowly; he bucked half-heartedly at the spurs.

Curley looked back at the oncoming dust. It was a big posse. The gray stopped and would go no more, and he sighed and dismounted, shot the horse through the head, and sat down on the slack, warm haunch to wait in the sun. “Boy,” he said again, “why would you do such a thing?” His hand fumbled once more after his mouth organ which he had left behind him.