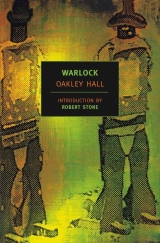

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

GANNON sat with his chair tilted back against the wall and his boot-tips just touching the floor, pushing the oily rag through the barrel of his Colt with the cleaning rod. He forced it through time after time, and held the muzzle to his eye to peer up the dark mirror-shine of the barrel. He tested the action and placed the piece, awkward with his bandaged hand, in its holster, and looked up to see Pike Skinner watching him with an almost ludicrous grimace of anxiety. The judge sat at his table with his face averted and his whisky bottle cradled against his chest.

Gannon tapped the wounded hand once against his thigh, then shot it for the Colt. His hand wrapped the butt gingerly, his forefinger slipping through the trigger guard as he pulled it free, his thumb joint clamping down on the reluctant cock of the hammer spring. He did not raise it, holding it pointed toward the floor.

“Christ!” Pike said.

It had not been as slow as all that, Gannon thought. He had never been fast, but he could shoot well enough. He felt very strange; he remembered feeling like this when he had had the typhoid and had waked finally with the fever broken. Then, too, all the outer things had seemed removed and unimportant, and as though slowed somehow, so there was much time to examine all that went on around him, and especially any movement seen in its entirety, component by component. Then, as now, there had been a very close connection between the willed act, and the arm, and hand and fingers that were the objects of the will; so that, too, his life and breathing had become conscious acts, and he could almost feel the shape of his beating heart, and watch the slow expansion and collapse of his lungs.

The judge drank, spluttered, and went into a coughing fit. Pike pounded him upon the back until he stopped. “They must be about through burying by now,” Pike said, scowling.

Gannon nodded.

“You just sit, son,” the judge said, in a choked voice. His eyes were watering, and he drank again and wiped his mouth. “You just let them go on out if they see fit, now, you hear?” he said feebly. “There is nothing gained anywhere if you are shot dead.”

“You let us handle them if they are calky,” Pike said. In a placating tone he said, “No, now, not vigilantes either, Johnny. There is Blaisedell down there and no reason for him not to be, and just some of the rest of us around. Now you hear, Johnny?”

“Why, I’m not going to hide in here,” Gannon said, and felt the necessity to grin, and, after it, the grin itself. He looked at the judge, whose face sagged in dark, ugly, bloated lines. “Nothing is gained if I sit it out in here, either.”

“You don’t have to prove anything,” Pike said. “You leave it to us, now. There is some of us got to stand now like we never did for Bill Canning. You leave us that.”

Gannon didn’t answer, for there was no point in arguing it further. Pike said, “They ought to be about through out there. I am going down.” He hitched at his shell belt, loosened his Colt in its holster, gave Gannon another of his confused and accusing glances, and disappeared.

When Pike was gone Gannon took out his own Colt again, and began to replace the heavy, vicious, pleasingly shaped cartridges in the cylinder.

“Blaisedell was right,” the judge said. “He said I would put too much on you and I have done it.”

“You put nothing on me, Judge. There is just a time and a place for a show. You know that.”

“But what place, and what time? Who is to know that?” The judge swung a hand clumsily to try to capture a fly that planed past his head. He contemplated his empty hand with bloodshot eyes, and made a contemptuous sound. “I saw you draw just now, son. Time you got that piece out, Jack Cade or either of the Haggins or any fumble-handed plowboy would have shot you through like a colander and had a drink to celebrate and rode halfway back to San Pablo.” He sighed heavily and said, “I thank you for saying I didn’t put it on you. Are you scared?”

Gannon shrugged. He felt not so much fright as a curious, flat anxiety. He was only afraid that it would be Jack Cade.

“I’m scared for you,” the judge said. “I don’t think you have got a Chinaman’s chance unless you let Pike and the marshal and those give you a chance. You too proud for that?”

“Proud’s nothing to do with it,” he said. It touched him that the judge felt responsible for this. “Well, maybe a little,” he said. “But if a deputy is going to be worth anything he can’t hole up when there is trouble.”

“All men are the same in the end,” the judge said. “Afraider to be thought a coward than afraid to die.”

Gannon rubbed his itching palm on the thigh of his pants, grimacing at the almost pleasant pain. The judge held the bottle up before him and squinted at it.

“Some men drink to warm themselves,” he said. “I drink to cool the brain. I drink to get the people out of it. You are nothing to me, boy. You are only a badge and an office, is all you are. Get yourself killed, it is nothing to me.”

“All right,” he said.

The judge nodded. “Just a process,” he said. “That’s all you are. What are men to me?” He rubbed his hand over his face as though he were trying to scrape his features off. “I told them they had put Blaisedell there, and put him there for the rest of us. I talk, and it makes me puke to hear myself talking. For Blaisedell is a man too. I wish to God I didn’t feel for him, or you, or any man. But do you know what whoever it was that shot down McQuown took away from Blaisedell? Who was it, do you suppose?”

Gannon shook his head.

“What they took away from him,” the judge went on. “Ah, I can’t stand to see what they will make of him. They will turn him into a mad dog in the end. And I can’t stand to see what they will do to you now, just when you—” He drank again. “Whisky used to take the people out of it,” he said, after a long time.

Footsteps came along the planks outside. Buck Slavin appeared in the doorway, carrying a shotgun. Kate entered a step behind him. “They are coming,” Kate said.

Gannon heard it now, the dry, protesting creak of a wagon wheel and the muffled pad of many hoofs in the dust. He got to his feet, and as he did, Buck raised the shotgun and pointed it at him.

“Now, you are not going out there, Deputy,” Buck said patronizingly. “There are people to deal with this. You just sit.”

“What the devil is this?” the judge cried.

Gannon began to shake with rage; for they had thought he would be glad of an excuse, and Kate had begged it and Buck furnished it. Kate stood there staring at him with her hands clutched together at her waist.

He started forward. “Get out of my way, Buck Slavin!”

Buck thrust the shotgun muzzle at him. “You will just camp in that cell awhile, Deputy!”

Gannon caught hold of the muzzle with both hands and shoved it back so that the butt slammed into Buck’s groin. Buck yelled with pain and Gannon wrenched the shotgun away and reversed it. Buck was bent over with his hands to his crotch.

“ Youmarch in there!” he said hoarsely. He grasped Buck’s shoulder and propelled him into the cell, locked the door, and tossed the key ring onto the peg. He leaned the shotgun against the wall. He didn’t look at Kate. The hoofs and the squealing wagon wheel sounded more loudly in the street.

“Now see here, Gannon!” Buck said in an agonized voice.

“Shut up!”

“Oh, you are brave!” Kate cried. “Oh, you will show the world you are as brave as Blaisedell, won’t you? I thought you had more sense than the rest behind that ugly, beak-nosed face. But go ahead and die!”

“That was a fool trick, Buck!” the judge said. “Interfering with an officer in the performance of his duty. And you ought to be jailed with him, ma’am, only it wouldn’t be decent!”

“Shut up, you drunken old fraud!” Kate said. Her eyes caught Gannon’s at last, and he saw that she had come to save him, almost as she had once saved Morgan; he felt awed and strangely ashamed for her, and for himself. He started out.

“We’ll send flowers,” Buck said.

“Why?” Kate whispered, as Gannon passed her. “ Why?”

“Because if a deputy can’t walk around this town when he wants, then nobody can.”

Outside, the sun was warm and painfully bright in his eyes as he gazed up at the new sign hanging motionless above his head. The sound of the wagon had ceased. He remembered to compose his face into the mask of wooden fearlessness, that was the proper mask, before he turned to the east.

The wagon had stopped before the gunshop in the central block. The San Pablo men had dismounted and there was a cluster of them around the wagon, and a few were entering the Lucky Dollar. Faces turned toward him. Some of the men, who had been moving toward the saloon, stopped, others moved quickly away from the wagon; they glanced his way and then across Main Street.

Blaisedell was there, he saw, standing coatless under the shadow of the arcade before the Billiard Parlor, one booted foot braced up on the tie rail; it was where he often stood to survey Main Street. His sleeves were gartered up on his long arms, a dark leather shell belt rode his hips. He stood as motionless as one of the posts that supported the roof of the arcade. Farther down were Mosbie and Tim French, and, on the comer of Broadway, Peter Bacon, with a Winchester over his arm. Pike Skinner stood before Goodpasture’s store, and in a group in Southend Street were Wheeler, Thompson, Hasty, and little Pusey, Petrix’s clerk, with a shotgun. His throat tightened as he saw them watching him; Peter, who was no gunman; Mosbie, who had railed at him most violently over Curley Burne; Pike, who he had begun to think was his sworn enemy, until today; Blaisedell, who had wanted to make this his own play; and a bank clerk, after all.

He started forward down the boardwalk. He flexed his shoulders a little to relieve the tight strain there. He stretched his wounded, aching, sweating hand to try to loosen it. His skin prickled. He wondered, suddenly, that he had no plan. But he had only to walk the streets of Warlock as a deputy must do, as was his duty and his right.

He crossed Southend Street with the Warlock dust itching on his face and teasing in his nostrils. Wash Haggin was standing spread-legged in the center of the boardwalk before the Lucky Dollar, facing him.

Old man McQuown was still in the wagon, beneath a shade rigged from a serape draped over four sticks. There was no one else in view on this side of the street.

“Dad McQuown,” he said, in greeting, to the wild eyes that stared at him over the plank side of the wagon. He halted and said, “I will do my best to find out who did it, Dad McQuown.”

He started on, and now Wash’s face was fixed in his eyes, Wash’s hat pushed back a little to show a dark sweep of hair across his forehead, Wash’s face set in a wooden expression that must be a reflection of his own face. Wash instead of Jack Cade because Wash was kin to Abe, he thought. He had a glimpse of Chet Haggin’s face above the batwing doors of the Lucky Dollar, and Cade, and Whitby and Hennessey shadowy behind them.

“I’ll trouble you to let me by, Wash,” he said.

Wash’s eyes widened a little as he spoke, and he felt a thrill of triumph as Wash sidled a step closer to the tie rail. There was the scuffing of his boots, then an enormous silence that now contained a kind of ticking in it, as of a huge and distant clock. He saw Wash’s face twist as he passed him and walked steadily on. Now the prickling of his skin was centered in the small of his back and the nape of his neck. Peter Bacon, across the street, was holding the Winchester higher; Morgan sat in his rocking chair on the veranda of the Western Star. He could see Blaisedell, too, now, as he came past wagon and team.

“Bud!” Wash cried, behind him.

He halted. The ticking seemed closer and louder. He turned. Wash was facing him again, crouching, his hand hovering. Wash cried shrilly, “Go for your gun, you murdering son of a bitch!”

“I won’t unless you make me, Wash.”

“Go for it, you murdering backshooting—”

“Kill him!” Dad McQuown screamed.

Wash’s hand dove down. Someone yelled; instantly there was a chorus of warning yells. They echoed in his ears as he twisted around in profile and his wounded hand slammed down on his own Colt; much too slow, he thought, and saw Wash’s gun barrel come up, and the smoke. Gannon stumbled a step forward as though someone had pushed him from behind, and his own Colt jarred in his hand. He was deafened then, but he saw Wash fall, hazed in gunsmoke. Wash fell on his back. He tried to roll over, his arm flopped helplessly across his body, and his six-shooter dropped to the planks. He shuddered once, and then lay still.

Gannon glanced at the doors of the Lucky Dollar; the faces there had disappeared. Then he had a glimpse of the long gleam of the rifle barrel leveled over the side of the wagon. He jumped back, just as a man vaulted into the wagon. It was Blaisedell, and old McQuown screamed as Blaisedell kicked out as though he were killing a snake – and kicked again and the rifle dropped over the edge of the wagon to the boardwalk.

He could see the old man’s fist beating against Blaisedell’s leg as Blaisedell stood in the wagon, facing the doors of the Lucky Dollar. No one appeared there for a moment, and Gannon started back to where Wash lay. But then Chet Haggin came out and knelt down beside his brother’s body, and Gannon turned away. The old man had stopped screaming.

He walked on down toward the corner. After a moment he remembered the Colt in his hand, and replaced it in its holster. There was the same silence as before, but it buzzed in his shocked ears. His hand felt hot and sticky, and, looking down, he saw blood leaking dark red from beneath the bandage. At the corner he turned and crossed Main Street, and mounted the boardwalk on the far side in the shadow. Peter didn’t look at him, standing stiffly with the rifle in his white-clenched hands. Tim’s eyes slid sideways toward him and Tim nodded once. He heard Mosbie whistle between his teeth. Blaisedell had returned to this side of the street, and leaned against a post, watching the wagon. Now Gannon could hear the old man’s pitiable cursing and sobbing, and he could see Chet still bent over Wash.

“I thank you,” he said, to Blaisedell’s back, and walked on. He looked neither right nor left now but kept his eyes fixed on the black and white sign over the jail doorway. Kate’s face appeared there briefly. He had made his turn through Warlock, as was his right, as was his duty; but his knees felt weak and the sign over the jail seemed very distant. He could feel the blood dripping from his fingers, and his wrist brushed the butt of his Colt as his arm swung.

“Hallelujah!” Pike Skinner whispered, as he came to the corner. He did not reply, and crossed Southend Street, feeling the stares of the men – not vigilantes – who were stationed there. Again he saw Kate appear in the jail doorway, but when he approached she disappeared back inside, and, when he entered, she stood with her back to him.

The judge sat hunch-shouldered at the table, his crutch leaning beside him, his bottle and hard-hat before him, his hands clasped between them. Buck’s face was framed in the bars.

“Got you in the hand, did he?” Buck said, in a matter-of-fact voice.

“I just broke it open again.”

The judge didn’t speak as he moved in past the table. He heard Kate gasp. “Your belt!” she cried. He reached back to feel a long gap in the leather and some cartridge loops gone. He sat down abruptly in the chair beside the cell door.

Kate stood facing him. He saw her stocking as she pulled up her skirt. She tore at the hem of her petticoat and then stooped to bite on the hem and pull loose a long strip. She took his hand and roughly bound the strip of smooth, soft cloth around it, and tore it again and tied the ends.

Then she stepped back away from him. “Well, now you are a killer,” she said, with her lips flattened whitely over her teeth.

“Who was it, Johnny?” Buck said.

“Wash.”

“What’re they going to do now?”

“I expect they’ll go out.”

“He’s got a brother, hasn’t he?” Kate said. The judge was regarding the whisky bottle, his face a mottled, grayish red, his hands still clasped before him.

Buck cleared his throat and said, “Well, you have made some friends this day, Gannon.”

“Friends!” Kate cried. “You mean men to think he is a wonder because he killed a man? Friends!” she said hoarsely. “A friend is someone who will say he did right and what he had to do, and hold to it. They will stew on this until they have figured he murdered this one like he murdered McQuown. I have seen it done too many times. Friends! They will—”

“Now, Kate,” Buck said.

“I didn’t murder Abe McQuown, Kate.”

“What difference does that make?” she cried at him. “Friends! A friend lasts like snow on a hot griddle and enemies like—”

“You are bitter for a young woman, miss,” the judge said.

Gannon hung his head suddenly, and bent down still farther. He felt faint and his stomach kept rising and swelling against his laboring heart, and he could taste bile in his throat. In his mind’s eye he saw not Wash Haggin’s wooden face, but the frantic dark face of the Mexican sweeping up the bank toward him still. “Bitter?” he heard Kate say, above the humming in his ears. “Why, yes, I am bitter! Because men have found some way to crucify every decent man, starting with Our Lord. No, it is not even bitter – it is just common sense. They will admire him for a wonder because he killed a man they wouldn’t’ve had the guts to go against. But they will hate him for it, because of that. So they will say he murdered him like he murdered McQuown. Or they will say it was nothing, with Blaisedell there to back him, and those others. They will say it for they are men. Don’t you know they will, Judge?”

“You are bitter,” the judge said, in the same dull voice. “And scared for him too. But I know men better than you, I think, Miss Dollar. They are not so bad as that.”

“Show me one that isn’t! Show me one. But don’t show them. Or they will kill him for it!”

“There are men that love their fellow men and suffer for their suffering,” the judge said. “But you wouldn’t see them for hatefulness, it looks like, miss.”

Gannon raised his head to look at Kate’s face, which was turned toward the judge – and it was hard and hateful, as he had said.

“I would show you Blaisedell for one,” the judge said.

“Blaisedell,” Kate whispered. “No, not Blaisedell!”

“Blaisedell. Hard as I have judged him, he is a good man. That knew better than you, miss, what had to be done just now. That let Johnny take his play and glory just now, for he needed them, with McQuown took from him. He is a good man. And I will show you Pike Skinner that thought Johnny threw this town down with Curley Burne, but backed him now all the same. And the rest of them out there. Good men, Miss Dollar! The milk of kindness is thick in them, and thicker all the time!”

“Thick as blood!”

“Thicker than blood. And will win in the end, miss – for all your sneering at a man that says it to you. So this old world remakes itself time and time again, each time in labor and in pain and the best men crucified for it. People like you will not see it, being bitter; as I have been myself, and so I know. So they can say a town like this one has its man for breakfast every morning—” He slammed his hand down on the table top, his voice rose. “But not killed to eat for breakfast any more! Not burnt on crosses to the glory of God any more! Not butchered up—”

The judge stopped and swung around in his chair as footsteps sounded outside. Gannon rose as Chet Haggin came into the doorway. Chet wore no shell belt, and there was a smear of blood on the breast of his blue shirt. He stood in the doorway staring at Gannon with burnt, dark eyes in his carefully composed face.

“I’m sorry, Chet,” Gannon said.

Chet nodded curtly. He glanced from Gannon to Kate, to Buck, to the judge, and then his burnt eyes returned. “I never thought you come back and shot Abe,” he said, in a harsh, flat voice. “I have known you some, Bud. So I know just now you killed Wash because there wasn’t anything else you could do, the way it was put. I come up here to tell you I knew that.”

Chet made as though to hook his thumbs in his belt, and grimaced and looked down. “Thought I’d better not start up here heeled,” he said, in an apologetic tone. “Things are scratchy out.”

The judge sat motionless with his chin on his hands. Kate stood tall and straight with her hands clasped before her and her eyes cast down.

Chet said, “Bud, we thought pretty low of you when Billy got killed. And said low things. Now I guess I know how you felt, for when you press to kill a man and he kills you to keep you from it, who is to blame? Anyway, I guess I know how you wouldn’t go against Blaisedell, and scared nothing to do with it.” His eyes filled suddenly. “For I won’t brace you, Bud. And I’m not scared of you!”

“I know you’re not, Chet.”

“They will say it. Be damned to them. I won’t come against you, Bud. But they will try to kill you, Bud. Jack– They won’t rest till they do it now. I won’t go against you, but I can’t go against what’s my own kin and kind! I can’t go against my own and side with Blaisedell like you have done. I can’t!” he cried, and then he stumbled back outside and was gone.

“Always said he was the white one,” Buck commented, and the judge gave him a disgusted look.

Gannon stood staring at the dusty sunlight streaming in the door. Presently he heard the creaking of the wagon wheels. He moved slowly past Kate to stand in the doorway. The team and wagon were coming down Main Street toward him, and the riders following in the dust it raised. Pike Skinner, who was still standing before Goodpasture’s store, waved to him to get back inside.

“Going out?” the judge asked.

“Looks like it.”

“You had better get out of that door, Johnny!” Buck said.

But he didn’t move, watching them come down Main Street, Joe Lacey and the breed Marko on the seat of the wagon, and the serape shading the old man in the bed behind them. The horsemen fanned out to fill the street. He watched for Jack Cade.

Cade had dropped a little behind the others. He rode with his shoulders hunched. His round-crowned hat was white with dust, his leather vest hung open; his purple and black striped pants were stuffed into his high boots. A fringed rifle scabbard hung slanting forward along his bay’s neck. He reined the bay toward the boardwalk, and behind him on the corner Gannon saw Pike Skinner lower his hand to his Colt.

The wagon rolled past him, the men on the seat staring steadily ahead. The old man’s eyes gazed at him over the side of the wagon, white-rimmed, sightless-looking, and insane. The riders had drawn their neckerchiefs up over their faces, and it was difficult to tell one from the other. They turned their faces toward him, like cavalrymen passing in review, but Jack Cade was riding toward him.

“ I’llkill you, Bud!” Cade said in a voice that was almost a whisper and yet enormously loud in the silence. Then he nodded, and set his spurs, and the bay trotted swiftly on to catch up with the others.

They rode on down the street behind the wagon, fading shapes in the powdery drifting dust, their passage almost soundless except for the occasional eccentric creak of the dry wheel. When they had almost gained the rim, he saw one of the horses rear and a shot rang out; and at once all the horses began to rear in a confused and antic mass, and all the riders fired into the air and yipped and whooped in thin and meaningless defiance.

There was a flat loud whack above his head and the sign swung suddenly. The shooting and whooping ceased as suddenly as it had begun, and, as though team, wagon, and horsemen had fallen through a trapdoor, they disappeared over the rim on the road back to San Pablo.

He looked up at the bullet hole in the lower corner of the new, still swinging sign, and went back inside.

“Was that Cade?” Kate whispered.

He nodded and heard her sigh, and she raised a fist and, like a tired child, rubbed at her eyes. There was a new and closer whooping in the street, and suddenly Kate moved to lean on the table and stare down at the judge.

“Everything is fine now, isn’t it?” she said. “Nothing to worry about now, is there? Oh, the good ones always win out in the end and it is all right if they get crucified for it, because—”

“Now, Kate,” Buck said. “I don’t know why you’re taking on so. It’s all over now, and he’ll have a lot to back him from now on.”

“But who is to stand in front of him?” she said, just as Pike Skinner ran in.

Pike leaped on Gannon, laughing and yelling and hugging him; then the others came until the jail was filled with them, all of them talking at once and coming up to slap his shoulder or shake his good hand, to examine and exclaim over the bullet scar on his belt, and ask what Chet had had to say. He didn’t see Kate leave, he was just aware suddenly that she was gone, and the judge gone. Someone had brought a bottle of whisky and was passing it around, and others were singing, “Good-by! Good-by! Good-by, Regulators, Good-by!…”

He thanked Pike, and thanked the others one by one as they came up to him. “Surely, Horse, surely,” Peter Bacon said. “It was a pleasure to see you and worth more than just standing there holding my boots down with a Winchester for ballast.” The whisky bottle was forced upon him time and again. Someone had let Buck out of the cell. He thought, with a sinking twisting at his heart, that there had not been such jollity and merriment as this in Warlock for a long time now.

He heard someone ask where Blaisedell was and French replied that he had not come up with them. He had wanted to thank Blaisedell.

He flinched as someone slapped him on the shoulder, and in the process brushed against his hand. Hap Peters stuck a finger through the hole in his shell belt. “Drink!” Mosbie was shouting, waving the bottle at him. “Drink to the rootingest-tootingest-shootingest-beatingest deputy this side of Timbuctoo!”

Mosbie forced the bottle on him, but he gagged on the sour whisky. Suddenly he could not stand it any more, and he made his way outside, and almost ran along the boardwalk to his room in Birch’s roominghouse.