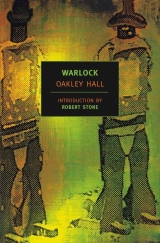

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

General Peach pivoted with the swing of his arm; grunting, he beat the stick down on the six-shooter in Blaisedell’s hand. The six-shooter fell. He slashed the stick with a heavier, duller crack across Blaisedell’s face. There was a moan from the crowd as Blaisedell fell back again. Miss Jessie screamed.

General Peach moved after Blaisedell with slow, awkward swings of his arm. His tight blouse split down the back and he grunted hugely with every stroke of the leather-bound stick, which flashed through its arc like a brown snake. Blaisedell crumpled and fell. The general straddled his body and brought the stick down again. Miss Jessie flung herself at him, screaming. He slashed at her and she fell back, clutching at her breast.

Then she raised the derringer in both hands and pointed it, as Colonel Whiteside bounded up the steps toward her crying, “No! No!” The hammer fell with the dry snap of a misfire and the colonel caught her in his arms, and wrested the little pistol away. The general slashed his stick down, and down again, unnoticing, “I!” he shouted suddenly, panting. “ Iam! I am!”

Then he desisted. He swung around toward the troopers and roared, “What are you men waiting for? Do I have to cut his onions before you will move?”

Major Standley started and called a command. Half the troopers dismounted, and, in single file, followed the major up on the porch, where Colonel Whiteside held Miss Jessie Marlow and General Peach stood astride Clay Blaisedell, mopping his red face with a blue handkerchief, panting. His vacant, small blue eyes watched the troopers enter, almost sleepily. One of them stumbled over one of the gold-handled six-shooters. The next kicked it off the porch. Colonel Whiteside held Miss Jessie’s arms, whispering to her; she was not struggling now.

“See that they find that man Tittle, Whiteside,” the general said suddenly. “Willingham wants him in particular.”

“Yes, sir,” Whiteside said.

Peach nodded solemnly. “Then nothing to do but load ’em up, take ’em out; see to it, Whiteside. Load ’em up, take ’em out,” he said, nodding again. “Willingham is a power at the convention, Whiteside. Oh, he is a powerful force at the convention. He will be useful to us, Whiteside.”

“Yes, sir,” the colonel said.

General Peach took off his great hat and wiped his pink bald head. Then he stepped clear of Blaisedell and walked heavily back down the steps. An orderly helped him mount the gray horse. MacDonald sat staring at the porch with his teeth showing in a kind of paralyzed grimace. Troopers began to come out of the door, herding the boarders before them. None of the miners looked at Miss Jessie, or at Blaisedell. The major came out.

“Where is Tittle, ma’am?” he said.

“I won’t tell you!”

“Now, ma’am,” the colonel said chidingly. “You would do just as well to tell us. We—”

“What will you do if I do not?” Miss Jessie cried. “Turn me over to your men for rape?”

“Now, ma’am!” the colonel groaned. He released her arms. Instantly she ran down the steps toward the general’s horse.

She cried, in a hoarse voice, “An army of jackals led by an old boar with a ring in his nose!”

“Hush!” Whiteside said, catching her again. “Hush now, please, ma’am! It is bad enough already. Hush, please!”

“Bloody old boar!” she cried. “Crazy old boar!” She began to sob wildly. General Peach stared down at her in silence, frowning. The men on the roof across the street averted their eyes.

Then there was a gasp as Blaisedell rose. He stood clinging to one of the posts that supported the roof of the porch, his face cruelly striped with red welted lines. Again Miss Jessie broke away from the colonel and ran to him, but now her cry was lost in a shout that went up from the corner, and General Peach awoke from his stupor as though galvanized by an electric shock.

“ Espirato!” someone was shouting, pushing his way through the crowd. “ Espirato!” He appeared between two of the troopers’ horses; it was Deputy Gannon. He ran toward the general.

“Oh, good God!” the colonel cried, as the general slashed the stick across the gray’s rump. The gray leaped forward toward the deputy.

“What’s that, man?” Peach roared. “What’s that you say?”

“Apaches!” the deputy cried. He grasped the gray’s bridle, his narrow, crooked-nosed face bent back to peer up into the general’s face. The major appeared and ran down the steps, and troopers hurried out of the door behind him. “It’s Apaches!” the deputy cried. “Joe Lacey just rode in to say they have killed a bunch of cowboys in Rattlesnake Canyon! He is at the saloon now!”

His further words were lost in shouting. The gray bucked away from his grasp as the general slashed back with the stick again.

“Whiteside!” Peach shouted. “Whiteside! Espirato, d’you hear? Do you hear, Whiteside? By the Almighty we will run him to earth this time, Whiteside! Standley, get your men mounted and ready!” The gray started forward through the townspeople. Men crowded around the deputy, shouting questions. No one looked now to see Miss Jessie Marlow helping Blaisedell back inside the General Peach.

The men descended from the rooftops, and the crowd moved away down Main Street. There were a few backward glances, and those made quickly and almost furtively. When they had all gone only Tom Morgan was left, leaning against the adobe wall of the Feed and Grain Barn, still staring at the porch. There was a fixed, contorted grin upon his face that was part a snarl, like that of a stuffed, savage animal, and part expectant, as though he were waiting for something that would change what had happened there.

62. JOURNALS OF HENRY HOLMES GOODPASTURE

June 5, 1881

IT WAS a thing I wish I had never seen, a man’s downfall and degradation. Poor Blaisedell; should he have pulled that trigger? I have fought the question, pro and con, to exhaustion in my mind. Yet was he not subscribed to it when he made his stand? And was it Miss Jessie’s will directing him to that stand? I will not blame her. Poor Blaisedell, we had already seen that incapacity that brought him low today; it was evident too when he was overrun by miners before the jail, that flaw of mercy or humanity, or of a fatal hesitation to be the aggressor at gunplay, or too much awareness of the consequences if he had pulled the trigger, on both occasions – not to himself but to this town.

How would I have him be different? If he had not had this flaw he would have been no more than a hired, calloused killer of men, and we would have turned against him finally for that very heedlessness. Instead, we will turn against him for his failure to be heedless, of consequences or of life, for seeming weakness, for that hesitation that was his ruin; for failure. Now he is pitied, and pity is no more than contempt beribboned and scented.

Pity and shame, a shame for him and for ourselves, who share it. Shame and pain, and pain must savagely turn upon its cause, which is Blaisedell. He should have fired.

Yet how could he have fired upon an old man, an insane old man, but one still to be honored for past deeds and for his position. Ah, but a cunning and treacherous insane old man, who, by the contrivance of turning his back upon Blaisedell, confessed that he knew Blaisedell to be honorable. And must have known that Blaisedell would not fire upon the man who is, after all, the embodiment of law and authority in this place.

Poor devil, he must wish himself dead, honorably dead. That is, perhaps, what should have been. He should have killed General Peach, and been himself instantly, unambiguously, and honorably killed by a volley of carbine fire. We would have crowned him then with laurels for tyrannicide.

Now, too late, I can formulate it: I asked of him only that he not fail. He has failed, yet how can a man be human and not fail? I remember once, before he came, jesting that he would have to be not of flesh and blood to succeed here. He did, until now, succeed, and was human, and is still. I could not grieve for him if he were not. So do most of us grieve; Warlock, for a day, will bleed for those wounds upon his face and spirit, and then, as a man will manage to thrust into oblivion something of which he is mortally ashamed, we will turn away from him.

My first thought, of course, was that Gannon was trying rather ridiculously to create a diversion. It was presently obvious that this was not so. Joe Lacey had indeed arrived in Warlock, with a frightful bullet-furrow across his forehead and a frightful story. It seems that the San Pabloites, including Lacey, Whitby, Cade, Harrison, Mitchell, Hennessey, and others – thirteen in all – were returning empty-handed from Hacienda Puerto, having been driven off by Mexicans, when, yesterday at nightfall, they were ambushed in Rattlesnake Canyon by a band of half-naked Apaches with their bodies horribly daubed with mud. Lacey swears (although this is not given much credence) that he marked Espirato among them, an old man supposedly very tall for an Apache. Any tall Apache immediately becomes Espirato, by which device he was, in the old days, capable of being seen in several places at once. The ambush was carried out with devilish cleverness. The men were riding closely grouped along a narrow and boxlike defile in which the whole group was enclosed at once, when there was a war cry as a signal, whereupon Apaches rose from behind every bush and rock – at least a hundred of them, Lacey says – and began to pour a torrent of hot lead down upon the hapless whites. In a few moments all but Lacey were dead. He saw with his own eyes one brave leap down to cut Whitby’s heart from his still living body, and others join to begin the usual disfigurement of the dead.

Lacey himself was in the lead, and miraculously escaped on down the canyon, riding at breakneck speed. He is sure no others escaped their doom.

I was fortunate enough to have entered the Lucky Dollar, where Lacey was steadying his nerves with Taliaferro’s whisky, before the rest of the crowd was blocked out by soldiers upon General Peach’s entry there. The General, after hearing Lacey’s story, announced his intention to depart immediately and with all his troops for the border. Colonel Whiteside interposed that Rattlesnake Canyon is in Mexican Territory, whereupon the General whirled as though he would strike his subordinate. “I will follow Espirato to hell itself, and be damned to the Mexican government!” cried he, to the accompaniment of cheers – for how fickle are men, to whom, a few minutes earlier, Peach had seemed a monster of superhuman powers. Whiteside continued to warn him that if he entered Mexican territory, trouble with that country would result, that he would certainly be court-martialed for it and end his days in disgrace. The General ordered him away contemptuously, and charged Major Standley with the preparation of the cavalry for the ride to the border.

Peach towered over his subordinates like a Titan over pygmies. Hate him as I must, I will admit he was at this moment every inch a general, and an impressive one. He seemed younger. He held himself more erect. His eyes flashed with resolution, and the commands he uttered were clear and terse; he seemed to have recovered himself completely since I had seen him last, in Bright’s City.

It was at this time that Willingham entered.[1] He is a short, rotund man with red whiskers fringing a cold and willful face. He began to seek the General’s attention, but Peach rebuffed him and, when Willingham persisted, directed one of his officers to escort the gentleman outside. Peach did this politely enough, but evidently had been holding himself in with some restraint, for when Whiteside again endeavored to make himself heard, Peach bellowed that he would be put under arrest if he uttered another word, and within twenty minutes General Peach and every officer and trooper had departed Warlock for the border.

The position of Willingham, MacDonald, and their henchmen, who have taken refuge in the Western Star Hotel, is perilous indeed, for the Medusa strikers have been released from the livery stable where they were confined, and a great number of them are now standing in Main Street outside the hotel, in ominous silence. Their mood does not seem to be one of violence – although as the day progresses and strong waters are imbibed, agitators listened to, and especially when the miners return this evening from the other mines, the mood may rapidly change, and if I were MacDonald and Willingham I would be shaking in my boots. I understand that Morgan has enlisted himself in Willingham’s party, and, with a number of foremen, stands guard at the hotel.

One of Blaikie’s hands has arrived, early this afternoon, with more news of the ambush in Rattlesnake Canyon. It now seems that Jack Cade and Mitchell have also escaped, and that their assailants were not Apaches at all, but Mexicans! This version of the ambush has immediately been accepted. For one reason, no doubt, because the possibility of Apaches on the loose and murderously inclined is an extremely unpleasant prospect to contemplate, and, for another, because the rumor has long been that McQuown and most of these same San Pablo men once ambushed Hacienda Puerto riders trailing rustled stock in Rattlesnake Canyon in exactly this same manner, masquerading as Apaches; and so it seems very likely that Don Ignacio’s vaqueros might have chosen a similar means to vengeance. Horrible though that vengeance seems, there is justice in it, and it is difficult not to wish that men such as Mitchell, and especially Jake Cade, had not been spared.

The Cowboy who brought in this news says he met the cavalry en route, and apprised them of his information – and was summarily brushed aside. It would seem, however, that the marauders will have put many miles between themselves and the border by now, if, indeed, they ever crossed it. And surely General Peach will not cross it himself, in pursuit of what the members of his staff, at least, must come to see are masqueraders.

There is laughter now about his wild, windmill-chasing ride, which, not many hours ago, had a valiant and glorious aspect. But the possibility that he will compound foolishness with idiocy, and lead his force into Mexico, is worrisome. Such an action could easily, in the present state of international relations, lead to reprisals, if not to war. To war in general we are not averse, but we decry it when we are in such an exposed position. Nor is General Peach a military commander in whom it is possible to have much faith.

The crowd of miners before the Western Star seems to have thinned out, and some say that their leaders, who had been let out of jail (the doctor was incarcerated with them!) are now meeting to decide upon a course of action. I fear they may run wild, knowing they have this respite in which to commit whatever arson and destruction they please, before Peach returns and they are rounded up again.

Blaisedell has not been seen. The subject is scrupulously avoided, and gossip is all over General Peach’s charge after the nonexistent Apaches. There is a general feeling of the fittingness of the slaughter of the rustlers, and I have heard it said that this ambush took place in exactly the same part of the Canyon as did the previous one, which it avenged. Sheriff Keller I saw in the Lucky Dollar, exceedingly under the influence of strong spirits; with him the judge, equally so. Many Cowboys are coming in from the valley. As usual, the news from Warlock has reached them on the wind, or through the voices of birds. I hope they have not come to gloat over Blaisedell’s fall. Theydid not accomplish it. The sight of him dropping mutely beneath General Peach’s bludgeon clings to me like an incubus.

[1] Director of a number of mining companies, and president of the board of Porphyrion and Western, “Sunny Will” Willingham was a prominent California politician and a former member of Congress.

63. THE DOCTOR CHOOSES HIS POTION

WORD had been sent out that the Medusa strikers were to meet on the vacant ground next to Robinson’s wood yard at five o’clock, and a little before that time the doctor set out from Tim Daley’s house in company with Fitzsimmons, Daley, Frenchy Martin, and the others, who, as Fitzsimmons had said, had been classified as goats rather than sheep by the fact that they had been incarcerated in the jail rather than in the livery stable with the rank and file. Old man Heck, in a sulk, had refused to attend the meeting.

The afternoon had been spent in argument over policy that had been, by careful indirection, a struggle for power. Old man Heck’s supporters had deserted him one by one, until finally even Frenchy Martin and Bull Johnson had been won over. Now the decisions, for better or for worse, lay with the doctor and Fitzsimmons, whom the goats had raised to leadership over themselves, and so over the sheep.

The doctor had been amazed by his own actions this afternoon. They had been entirely foreign to what he had known of himself, Dr. David Wagner. The hatred engendered within the struggle to manipulate words and men just passed, had far outstripped any felt for the Medusa mine, for MacDonald, and for the mineowners. He was not even disgusted with himself to realize that he was as much a subject to this as old man Heck or Bull Johnson. His jealousy, whenever any man had risen to challenge him, had been ruthless, his pleasure, when he had won each separate skirmish, triumphant; he was contemptuous now of those he had beaten.

Fitzsimmons had clung to his coattails throughout, and he had been content to have it so, although he knew, too, that Fitzsimmons was jealous of him, and that he could look forward to a further struggle for power, one day, with Jimmy Fitzsimmons. He did look forward to it, to test again this thing newly discovered in David Wagner against the iron will and cunning, the pure thrust of ambition in a boy more than twenty-five years younger than he.

Fitzsimmons glanced sideways at him and winked, solemnly, and he nodded in reply.

Behind them Daley and Martin were talking in low, excited voices. Several whores peered worriedly from the cribs along the Row, and the dark, wooden faces of Mexican women watched them from the porches of the miners’ shacks along Peach Street. Warlock seemed apathetic after an eventful day. Now, the doctor thought, his anger against MacDonald must be regenerated, and yet this done in such a way that he could temper the mood of the strikers at the meeting to the proper course. He began to ponder what he must say to them – different words entirely from those of this afternoon.

“Do you know what, Doc?” Fitzsimmons said, in a low voice. “There is not a miner in this town knows what to do now. They will be so pleased to have us tell them they will wag their tails.”

“And do just the opposite,” he said, and smiled.

“Not if we tell them what they are going to do is what they wantto do.”

“I think there are more than old Heck who want to burn the Medusa still. Or more than ever.”

Fitzsimmons shook his head condescendingly. “They are too scared, Doc. Just so nobody says they are scared. We had just better be damned sure nobody speaks up to say we had better settle quick before the cavalry gets back. That’s all we have to watch out for.”

“And make sure we show Willingham we think he is in rather a worse position than we are.”

“Expect it would be a good idea to get up a torchlight parade tonight?”

“I think it would be very effective, and a good thing for you to turn your energies to. If you are sure you could control it.”

“I could control it, all right,” Fitzsimmons said stiffly, and glanced at him sideways again.

The little procession passed the wood yard and turned into the vacant property, which had been used for miners’ meetings since Lathrop’s time. There were a number of miners there already.

The doctor stopped and looked around to meet the eyes that were all fixed upon him. It was as though they knew instinctively that he had been chosen, and deferred without question to the choice. “Doc,” Patch said, in grave greeting, and then many of the others took it up. Their tone was different from that of their usual greetings – a pledge of loyalty that had a suspended skepticism in it. They greeted Fitzsimmons by name too, but less deferentially.

“Frenchy,” the doctor said, as the rest of the men from Daley’s house came up to group around him, “will you see that those planks are set up on the barrels so the speakers will have a place to stand?” Fitzsimmons grinned crookedly as Frenchy went to do it, and the doctor realized why he had spoken so loudly, and to Martin in particular.

“Doc!” Stacey, with his bandaged head, was hurrying toward him. Stacey raised a hand and broke into a trot. “Doc,” he panted, as he came up. “You had better come. Miss Jessie needs you at the General Peach.”

He felt Fitzsimmons’ eyes. “I can’t come now,” he said curtly. But all at once what had happened at the General Peach, which he had tried to put from his mind as irrelevant, crushed down upon him, and he felt pity for Jessie like a dagger stroke. But not now, he almost groaned; not now. He could not go now.

“It was the marshal sent me,” Stacey whispered. Beneath his muslin turban his freckled forehead was creased with worry. “He says she has got the nerves very bad, Doc.”

He nodded once. “Get my bag from the Assay Office, will you?” He turned to Fitzsimmons, whose eyebrows rose questioningly in his bland face. “Jimmy, I must go and see about Miss Jessie. You will have to do your best here until I get back.”

Fitzsimmons nodded, and then on second thought frowned as though it were a terrible burden and responsibility. “I will do my best, Doc,” Fitzsimmons said, massaging the torn knuckles with which he had made sure of his future. “You hurry,” he said.

“I will,” he replied grimly. He left the lot, ignoring those who called after him; he almost ran down Grant Street to the General Peach. Jessie’s door was closed, but he could hear her voice raised shrilly inside her room. Blaisedell opened the door for him.

He stared in shock at Blaisedell’s face. It was cross-hatched with great red welts, and his bruised eyes were swollen almost closed. “Thank God you have got here,” Blaisedell said, in a low voice. “You had better give her something. She is—”

“David!” Jessie cried, as he entered past Blaisedell. She stood in the center of the room facing him. Her white triangle of a face looked wasted, as though the fire that blazed in her eyes was consuming the flesh around them. Her face contorted into a wild grimace that he realized was meant to be a smile.

Blaisedell closed the door and came up beside him, moving as though he were sore in every fiber. He sounded exhausted. “She wants us to lead the miners up to burn the Medusa mine,” he said. “I have been trying to tell her it is – not the right time. I thought if you could give her something to quieten her,” he whispered.

“It is the time!” Jessie cried. “It is the time now! David, we will lead them, and we will—”

“Lead the miners, Jessie?” he broke in, and the words seemed a mockery of himself.

“Yes! We will ride up to the Medusa at the head of them, an army of them. How they will cheer and sing! There are barricades there, they say, but that cannot stop us! Oh, Clay!”

“Jessie, Blaisedell is right, I’m afraid. It is not the time.”

“It is the time! The cavalry has gone, and – and we have to do something!” She had a handkerchief in her hands, which she kept winding around one hand and then the other.

“We don’t have to do anything, Jessie,” Blaisedell said in a patient voice.

Her sunken, blazing eyes stared at Blaisedell, shifted to stare at the doctor; it was as though she were looking past them both to the Medusa mine, to glory or redemption – he did not know what. She pulled the handkerchief tight between her hands again. “David,” she said calmly. “You must help me make him understand.”

There was a knock. “That is Stacey with my bag,” he said to Blaisedell, who went to open the door. He took Jessie’s hands. The handkerchief was wet with perspiration, or with tears. He smiled reassuringly at her and said, “No, Jessie, I’m afraid it really is not the right time. Everything is very confused right now. But maybe tomorrow or the next day you and—”

“Now!” she cried, and her voice was suddenly deep with grief. “Oh, now, now!” She swung toward Blaisedell. “Oh, it must be now, before they forget him. Clay, it is for you!”

He took the bag from Blaisedell, and the bottle from it. There was a glass on the bureau and he filled it with water from the pitcher, and stained the water with laudanum. Behind him Jessie said despairingly, “Clay, it is for your sake!”

In the mirror the doctor saw the agony and revulsion written on Blaisedell’s cruelly bruised face. Jessie flew to him and pressed her face to his chest, her ringlets flying as she turned her head wildly from side to side, murmuring something to Blaisedell’s heart he neither could hear nor wished to hear. Blaisedell stared at him over her brown head as, awkwardly, he patted her back.

The doctor indicated the glass, and Blaisedell said, “Jessie, Doc has got something for you.”

Instantly she swung around. Her face darkened with suspicion. “What’s that?”

“It is some laudanum to let you rest.”

“Rest?” she cried. “Rest! We cannot rest a moment!”

“You had better take it, Jessie,” Blaisedell said, in the gentle voice.

The doctor raised the glass with the whisky-colored liquid in it to her, but she lifted a hand as though she would strike it to the floor. “Jessie!” he said sharply.

Her shoulders slumped. She closed her eyes. She began to sob convulsively. She rubbed her knuckles into her closed eyes and swayed, and Blaisedell put an arm around her. The doctor could see the sobs tearing at her frail body. They tore at him as well; with each one he was wrenched with pity for her, and with anger at Clay Blaisedell and the world that had broken her. His hand shook with the glass.

“Drink it, Jessie.”

Obediently she drank it down, and he went to turn the coverlet back on the bed. Blaisedell helped her to the bed and she lay down with her hands over her face, her fingers working in her tangled ringlets, her head moving ceaselessly from side to side. The doctor pulled the coverlet up over her as Blaisedell stepped back toward the door.

“I will be going now, Doc,” Blaisedell said in his deep voice, and he turned to meet the blue, intense gaze that was almost hidden beneath the swollen lids. Blaisedell said it again, not aloud, but with his lips only, and nodded to him.

“We will do it tomorrow!” Jessie cried suddenly. She raised her head and her eyes swung wildly in search of Blaisedell. “We will lead them to the Medusa tomorrow, Clay. Tomorrow may not be too late!”

“Why, no; tomorrow won’t be too late,” Blaisedell said, and smiled a little; then he went out, gently closing the door behind him.

The doctor sat down on the bed beside Jessie as she laid her head back again. She closed her eyes, as though she would be glad to rest. As he heard Blaisedell’s step upon the stairs he put down the glass and smoothed his hand over her damp, tangled hair.

He glanced up at the mezzotint depicting Cuchulain in his madness, and felt the pain and fury convulse his heart. So Blaisedell would leave, and damned be his soul for ever having come, for having enchanted her, for leaving her forever in the circle of flames and thorns. And the miners and their union? he thought suddenly. There was no choice. He smiled down at her and smoothed his hand over her hair.

“The miners are meeting now, Jessie,” he said. “Tomorrow will be time enough.”

She nodded and smiled a little, but did not open her eyes. “It would be better today,” she said in a small, clear voice. “But he is tired and hurt. I shouldn’t have blamed him so. I shouldn’t have called him a coward. What a strange thing to say of him!”

“He knew you were disturbed.” He looked down at the strong jut of her brows over her sunken, closed eyes, the whitening of her nostrils as she breathed, the determined set to her little chin.

“Oh, I am so glad I thought of it!” she said. “For it will change everything. We will ride, of course, and they will march behind us. We—”

“Tomorrow,” he whispered. “Tomorrow, my dear.”

He saw her face crumple; she began to sob again, but softly. She said in the small voice, “But you see why I must make him do it, don’t you, David? Because what happened here was my fault.”

“No, Jessie,” he said. “Jessie, you had better try to rest now.”

She fell silent, and after a time he thought she must be asleep more from exhaustion than from the effect of the opiate. He left off stroking her hair and gazed at the window, wondering how the miner’s meeting was progressing. He felt detached from it now, but there were a few things he would have liked to say. He would have liked to treat with Willingham for them; he thought he would have enjoyed crossing swords with Willingham.

Jessie said sleepily, “He was hurt and sick at heart, and I was so furious– He wanted to leave here tomorrow, he and I. To go somewhere else, and he said he would change his name. It made me so angry that he should think of changing his name! But I should have understood that he was hurt and sick at heart. Oh, dear God, I thought that monster had destroyed him! But it is silly to give in so easily when—”

“Rest,” he said. “You must rest.”

Again she was silent. He thought of her and Blaisedell leading the miners and wondered if it was any more insane than his trying to lead them himself. He gazed at his world through inward eyes and saw all his ideals and aspirations crumbling gray and ineffectual. He saw himself a fool. Much better, he thought, a torchlight parade than what he would have brought them, if he could have brought them anything; how much finer the flame of the Medusa stope mounting the shafthead frame against the sky, than the gray ashes of reason. He had deluded himself with his ideals of humanity and liberality, but peace came after war, not out of reason. They would have to have fire and blood to make their union. So it had always been, and revolutions were made by men who conquered, or who died, and not by gray thought in gray minds. Peace came with a sword, right with a sword, justice and freedom with swords, and the struggle to them must be led by men with swords rather than by ineffectual men counseling reason and moderation.