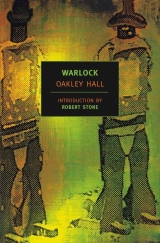

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“What did you mean,” he said slowly, “that the four or five others was badmen mostly?”

She said, in a voice so thick he could hardly understand her, “I am sick and tired of talking about Clay Blaisedell and who he killed.”

“I’m sorry. I guess it’s not a thing women are interested in much.” He tried desperately to think of something to say that would interest her, but it seemed to him that he didn’t know anything that would interest anybody. He wondered why she had gotten so angry.

“I’ve heard people saying you’d come out here to start up a dance hall,” he said, tentatively. “Seems like it would be a good tiling.”

She shrugged. Then she sighed and said, “I don’t know. Maybe I am waiting to see if this town is dying off too.” Something in the way she said it made him think it was a kind of apology for her anger, and after that it was almost all right again. They discussed the rumors that wages were going to be dropped at the mines, and she told him of the strike she had seen at Silver Mountain. She regarded him brightly now when he spoke, and so he found himself not so tongue-tied, although he marveled at how much more she knew, and had seen, than he. It was almost like talking to a man, and almost he could forget he was having supper with Kate Dollar in her house and alone, and that they were man and woman. But he would be brought back to it sharply from time to time, by something she said, or by some movement, and it was a very intense thing to him, except that it always made him begin to wonder again what had brought her to Warlock, who she was and what she was; but now he did not want to know. And he marveled too at how fine-looking she was in the lamplight, and at how soft her sharp black eyes could be sometimes, and the crooked way her mouth twisted when she smiled the smile he liked. He could not keep his eyes from the soft shadows her lashes made upon her cheeks.

Then she asked about McQuown. “What sort is he? I’ve heard a lot about him since I’ve been here, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen him in town.”

“He and Curley are in tonight. I guess on their way up to Bright’s for the trial.” He paused, to see if she was really interested; she was watching him intently. “Well, he is a rustler, mostly,” he went on. “I know him pretty well. He took Billy and me on to work for him after our father died – the Apaches’d run off all our stock.”

“How bad is he?”

He laughed shakily and said, “Why, Kate, I guess I don’t like to talk about him sort of the way you don’t about Blaisedell.”

She touched a finger to the corner of her mouth. She looked wary, suddenly. “I see,” she said. “You are against McQuown. So you are for Blaisedell.”

“No, that’s not so. Not like Carl is; not—” He stopped and looked down at his hands. “Maybe I am in a way,” he said. “For Abe is bad. Worse than he ought to be, and worse all the time, it seems like. I used to think pretty high of him.”

“But you left,” she said. “You left and your brother stayed on there.”

He stared down at his hands. He was going to tell her; it surprised him that he was. It seemed to him that Kate was gathering information not because she was interested in him, but for some purpose of her own that he had no way of deciphering. Yet, he thought, he would tell her, and only waited to get it calm and in proportion in his mind, so that he could tell it correctly.

“It was eight or ten months ago,” he said. “Maybe you’ve heard about it. Some Mexicans that was supposed to have been shot by Apaches in Rattlesnake Canyon. Peach came down with the cavalry. I guess everybody thought it was Apaches.”

“I’ve heard about it. Somebody said it was McQuown’s men dressed like Apaches.”

He nodded, and wet his lips. “We’d rustled more than a thousand head down at Hacienda Puerto,” he said. “But Abe wasn’t along. Abe always ran things like that pretty well, but he wasn’t along that time. He was sick, I guess it was, and Curley and Dad McQuown was running it, but there was nobody so clever as Abe. Anyway, they just about caught us, and Hank Miller was shot dead, and Dad McQuown shot and crippled. We lost all the stock, and they trailed us pretty close all the way.

“We got across the border all right, but then we found out they were coming right on after us. Abe was there by then, for Curley had rode the old man back to San Pablo. So a bunch of us stripped down and smeared ourselves with mud and boxed those Mexicans of Don Ignacio’s in Rattlesnake Canyon. We killed them all. I guess maybe one or two got away down the south end, but all the others. Seventeen of them.”

He picked up his coffee cup; his hand was steady. The coffee was cold, and he set the cup down again.

“That’s when you left?” Kate said; she didn’t sound shocked.

“I had some money and I went up to Rincon and paid a telegrapher to apprentice me. I thought it would be a good trade. But he died and I got laid off. So I came back here.”

It struck him that he had been able to tell her all there was to know about him in a few minutes. He shifted his position in his chair and his scabbarded Colt thumped noisily against the wood. He went on. “I can’t say I didn’t know what Abe aimed to do there in Rattlesnake Canyon. I knew, and I was against it, but everybody else was for it and I was afraid to go against them. I guess because I was afraid they’d think I was yellow. Curley wouldn’t go, though; he wouldn’t do it. There was some others that didn’t like it. I know Chet Haggin didn’t. And Billy was sick – to his stomach, afterwards. But he stuck down there. I guess he figured it out some way inside himself so it was all right, afterwards. But I couldn’t.”

“If you don’t like to see men shot down you are in the wrong business, Deputy,” Kate said.

“No, I’m in the right business. I was wrong when I went up to Rincon – that was just running away. There is only one way to stop men from killing each other like that.”

He looked up to see her black eyes glittering at him. She smiled and it was the smile he did not like. She started to speak, but then she stopped, and her eyes turned toward the door. He heard quiet footsteps on the porch.

He rose as a key rattled in the lock and the door swung inward. A short, fat, clean-shaven miner stood in the doorway, in clean blue shirt and trousers. His hair gleamed with grease.

“Oh, hello, Mr. Benson,” Kate said. “Meet Mr. Gannon, the deputy. Did you want something, Mr. Benson?”

The miner shuffled his feet. He backed up a step, out of the light. “I just come by, miss.”

“I guess you came by to give me the other key,” Kate said. “Just give it to Johnny, will you? He’s been asking for it, but I’d thought there was only one.”

“That’s it,” the miner said. “Remembered I had this other key here and I thought I’d just better bring it by before I went and forgot, the way a man does.”

Gannon stepped toward him, and the miner dropped the heavy key into his hand. The miner watched it all the way as Gannon put it in his pocket.

Kate laughed as he fled, and Gannon closed the door again. He couldn’t look at Kate as he returned to the table.

“He’s sorry he rented it so cheap,” Kate said.

“I guess I’d better talk to him tomorrow.”

“Don’t bother.”

He stood leaning on the back of his chair. “Anytime anybody fusses you, Kate. I mean, there’s some wild ones here and not much on manners. You could let me know.”

“Why, thank you,” she said. She got to her feet. “Are you going now?” she said. Dismissing him, he thought; she had just asked him for supper because of the miner.

“Why, yes, I guess I had better go. It was certainly an enjoyable supper. I surely thank you.”

“I surely thank you,” she said, as though she were mocking him.

He started to put the key down on the table.

“Keep it,” she said, and his hand pulled it back, quickly. It was clear enough, he thought. He tried to grin, but he felt a disappointment that worked deeper and deeper until it was a kind of pain.

He started around the table toward her. But something in her stiff face halted him, a kind of shame that touched the shame he felt and yet was a different thing. And there was something cruel, too, in her face, that repelled him. Uncertainly he turned away.

“Well, good night, Miss Dollar,” he said thickly.

“Good night, Deputy.”

“Good night,” he said again, and took his hat from the hook and opened the door. The blue-black sky was full of stars. There was a wind that seemed cold after the warmth inside.

“Good night,” Kate said again, and he tipped his hat, without looking back, and closed the door behind him.

Walking back toward Main Street he could feel the weight of the key in his pocket. He wondered what she had meant by it, and thought he had been right about it at first. He wondered what had happened inside her that had showed so in her face at the end; he wondered what she was and what she wanted until his mind ached with it.

26. JOURNALS OF HENRY HOLMES GOODPASTURE

March 2, 1881

JED ROLFE in on the stage this afternoon, and everyone gathered around him to hear about the first day of the trial. Evidently the delay came about because at the last moment General Peach decided he would hear the case himself, as Military Governor, from which illegal and senile idiocy he was finally dissuaded. General Peach, however, did sit in at the trial and interrupted frequently to the harassment of everyone and the baffled rage of Judge Alcock. Peach is evidently inimical to Blaisedell, for what reason I cannot imagine. My God, surely Blaisedell cannot be found guilty of anything! Yet I must remind myself that anything is possible in the Bright’s City court.

If Blaisedell were to be found guilty I think this town would rise almost to a man and ride into Bright’s City in armed rebellion to free him. Opinion has swung violently back to his behalf in light of this newest report, and his critics are silent. Miss Jessie Marlow in my store this afternoon ostensibly to purchase some ribbon, actually to learn if I had heard anything beyond the news Rolfe had brought. I had not, and could only try to reassure her that Blaisedell would be speedily acquitted. She was sadly pale, ill-looking, and far from her usual cheerful self, but she thanked me for my pitiful offering as though it were of value.

McQuown’s absence from Bright’s City’s courthouse has been remarked upon. He and Burne passed through Warlock on Sunday, and it was presumed they were en route to the trial. But only Burne was there; indeed, he seems to have been the only other San Pabloite other than Luke Friendly to appear. Rolfe said he heard that Burne and Deputy Schroeder exchanged hot words upon the courthouse steps, and would have exchanged more than words had not Sheriff Keller intervened. McQuown is no doubt more frightened that Blaisedell will be acquitted and return, than we are that he will not.

March 4, 1881

Buck Slavin, the doctor, Schroeder, et al. back. The jury is deliberating. They had waited over a day after the jury had left the box, but it was still out. They seem certain Blaisedell will be acquitted, and that the jury’s delay is only to enjoy as many meals upon the county as possible. Still, I notice that they seem worried that Luke Friendly’s outrageous lies may have told heavily against Blaisedell. Buck is bitter about the prosecuting attorney, Pierce, and that Judge Alcock did not cut him short more often than he did.

Evidently Pierce sought to inflame the jury with Billy Gannon’s youth, with the fact that less than a month ago the three Cowboys had been declared innocent in the same court, and with Blaisedell’s “murderous presumption” in setting aside the court’s decision and declaring himself “Judge and Executioner.” Buck says that the same rumor we have had here – that Morgan and Blaisedell were actually the road agents themselves, and murdered the “innocents” in an effort both to silence and permanently affix the blame on them – has been sown in Bright’s City, and, although not much believed there (Bright’s City has not seen as much of McQuown as we have, but they have seen enough) had evidently been heard by Pierce, and it was Pierce’s hints and implications along these lines that Buck felt Judge Alcock should have dealt with more firmly. As all agree that Friendly was a poor witness against Blaisedell, so do they agree that Morgan was the best witness in Blaisedell’s behalf; that he was cool and convincing, and gave as good as he got from Pierce, several times calling forth peals of laughter from the courtroom at the prosecutor’s expense.

From all I have heard I am glad I did not attend the trial. Poor Blaisedell; I pity him what he has gone through. Yet it was at his own instigation, and I am certain no charges would have been brought against him had he not wished it. Buck says, however, that he has been most calm throughout, and apparently took no umbrage at Pierce’s blackguardly accusations.

“What stronger breastplate than a heart untainted?

Thrice is he armed that hath his quarrel just;

And he but naked, though locked up in steel,

Whose conscience with injustice is corrupted.”

March 5, 1881

Blaisedell was acquitted yesterday. Peter Bacon arrived this morning with the news, having ridden all night. I sent a note around immediately to Miss Jessie, expressing my pleasure at hearing it, but there was no reply other than her verbal thanks to my mozo.

Now that Blaisedell is free and absolved, I am neither pleased nor relieved. The blackguardly statements with which Pierce harangued the jury, the jury’s inexcusable delay, Friendly’s damnable lies about what happened in the Acme Corral, and General Peach’s actions throughout [1] – how must these have affected him? He must have gone to court wishing absolution, and received only a poor, grudging, and besmudged verdict in his behalf. The official verdict, however, will not affect the verdict here, and I think in days to come there will be bad blood between Warlock men and Bright’s City men. Although I will say that the Bright’s City paper has treated Blaisedell with great respect in its columns and especially in its editorials, and I will congratulate Editor Jim Askew on these when next I see him.

I find myself deeply emotionally subscribed to all this. It seems to me that I, and all of us here, have a stake and an investment in the Marshal. He has produced, and, looking back, I see that he did from the beginning produce, an intense division for or against him. But Clay Blaisedell is not the rock upon which we are divided, he is only a symptom. We do not break so simply as some think into the two camps of townsmen and Cowboys. We break into the camps of those wildly inclined, and those soberly, those irresponsible and those responsible, those peace-loving and those outlaw and riotous by nature; further, into the camps of respect, and of fear – I mean for oneself, and for all decent things besides. These are the poles between which we vibrate, and Blaisedell has only emphasized the distance between them. It is too simple perhaps to say that those who fear themselves and fear their fellow men, fear and hate Blaisedell, while those who respect themselves, and Man, respect him. Yet I hold that this is true in a broad sense.

For the arguments continue, what happened in the Acme Corral compounded by the Bright’s City court and those who spoke there. I feel strongly that not merely I, but everyone here, sees himself affected personally by all this, and that, somehow, the truth or falsity of the whole affair reflects through and upon each of us. Fine points are argued as heatedly as the whole – how many shots, how many paces, who was stationed in exactly what position, and so on ad infinitum. So must the schoolmen have argued in their day, in their own saloons, the number of angels who could dance on the head of a pin.

[1] General Peach evidently, upon one occasion, shouted down the judge to say that Blaisedell should properly have been tried by a military tribunal, and that he, General Peach, would have had him shot. Why the military governor was not declared in contempt of court for his interference is perhaps understandable, and references to his peculiar actions, most delicately handled, are contained in the Bright’s City Star-Democrat’sreports of the trial.

27. CURLEY BURNE AND THE DOG KILLER

CURLEY rode in from the river on his way back to San Pablo from Bright’s City, blowing on his mouth organ. The music was pleasant to his ears in the silence around him, and the sun was pleasant upon his back as the gelding Dick plodded over the bare brown ridges and down the grassy draws. The Dinosaurs towered to the southwest with the sun on their slopes like honey, and from the elevation of the ridges he could see the irregular line of cottonwoods marking the river’s course toward Rattlesnake Canyon.

His cheerful mood vanished as he saw the chimney of the long-gone old house, and the windmill on the pump house. He was not bringing good news from Bright’s City.

Finally he came in sight of the ranch house, low to the ground and weathered gray as a horned toad; and now he could see the bunk-house, cook shack, horse corral – the porch of the ranch house. There were two figures seated there.

Going down the last slope Dick quickened his pace expectantly. Curley dropped the mouth organ back inside his shirt, flicked Dick with his spurs, and went down toward the house at a run, bending low in the saddle with his hat flying off and its cord cutting against his throat. He drew up with a yell before the porch, dismounted in a whirl of dust and barking dogs, and went up the steps. The other man he had seen was Dechine, Abe’s neighbor to the south, dropped in to pay a call. Dad McQuown was lying on a cot in the sun.

Abe sat staring at the mountains with his hat tipped forward to shade his face, scratching a thumb through his beard. He was leaning back with his boots crossed up on the porch rail.

Curley said, “Well, howdy, Dechine. How’s it?”

“Fine-a-lee,” Dechine said, fanning dust away with his hat. He was a short, pot-bellied fellow with little reddened eyes and a nose like half a red pear stuck to his face.

The old man propped himself up on one elbow. “Well, what happened, Curley? They set him loose?”

“They did,” he said. Abe sat there silently, staring off at the Dinosaurs with the long creases in his cheeks like scars. All the starch had gone out of him since the boys had got killed in the Acme Corral; sometimes he acted as though there were nothing left in him at all.

The old man spat tobacco juice in a puddle beside his pallet, swiped at his little red mouth, and said, “Buggers.”

“I was just telling Abe, here,” Dechine said, “how people has got down on Blaisedell in Warlock there, over murdering those poor boys.”

“One of them’s not Carl,” Curley said. “I don’t know what’s got into Carl. Used to be a man could get along with him.”

“You have trouble with Schroeder?” the old man said eagerly.

“We went and scratched some. He is taking lawing pretty hard.”

“He is one of those thinks Blaisedell is probably Jesus Christ there,” Dechine said. “I’ve been telling Abe they are not all like that, though.”

Still Abe didn’t move, didn’t speak. Curley took out his mouth organ, then put it back. He didn’t know what had happened to everybody but it had begun to seem to him more and more that it was time to move on. Everything was nasty now, except when he was off by himself. Dad McQuown scraped his nerves like a rasp, and it was poor to see a man scared loose from himself, which was the case with Abe, who was the best friend he had ever had. He had got Abe to come as far as Warlock with him on his way up to Bright’s City, and Abe hadn’t said as much as two words the whole time and had acted as though he were madder at him, Curley, than at anybody else. He had stayed in the Lucky Dollar about an hour and then headed on back without an aye, yes, or no, except to say Warlock turned his stomach now. Everything had turned bad because of Blaisedell sitting in Warlock like a poison spider in its dirty web.

“Where’s Luke?” Abe asked.

“Well, he decided he’d go over toward Rincon and see what the country’s like there. Said he was tired of the territory.”

Abe made a sound that was a fair try at a laugh. The old man yelled, “Hollow pure yellow son of a bitch!” He began fretting and cursing to himself, and scratching viciously at his legs. They itched all the time now, he said.

“Well, now,” Dechine said. “I didn’t get up to the trial there, but I heard Blaisedell had himself an awful hard time up there.” His little red eyes sought Curley’s. “Isn’t that right, Curley?”

“Joy to see it. I wished you’d been there, Abe.”

Abe said nothing.

“Well, I mean,” Dechine said. “What I come by to tell you, Abe. I was talking to Tom Morgan, kind of talking around it to him there, and he sounded like Blaisedell wasn’t going to stand for being pissed on up there at Bright’s like he was. Sounded like he thought Blaisedell might move on.”

“He won’t move on,” Abe said. “He’s got work to do still.” Curley watched him stretch, and knew it was a fraud. “Killing to do yet,” Abe said.

Curley averted his eyes to see Dechine scowling down at his knees, and the old man grimacing horribly.

Dechine said, “There is this new woman up in Warlock. Kate Dollar her name is, and high-toned as that madam they used to have at the French Palace there. Won’t have anything to do with anybody, but I see her passing the time there with Johnny Gannon the other day. Never thought of him much as being a long-boy, before.”

“Hope she gives him the dirty con,” the old man said. “Any son of a bitch that would stand by and see his brother burnt down by that hog butcher.”

“Dog killer,” Abe said, in that way he had, as though he were talking to no one. “He will come back because he didn’t get all the dogs killed yet.”

“I swear!” Dad McQuown cried. “It makes a man want to puke to hear a son of mine talk like you do!”

Abe didn’t even appear to hear. Dechine was studying his knees some more.

“Son, what’s got into you?” the old man said. “I never heard such fool talk.”

Curley heard snarling beneath the porch. One of the dogs dashed off around the corner; it was the big black bitch, with the little feisty brown one after her. Abe stirred a little, and moved his shoulders in his grease-stained buckskin shirt.

“Why, they make you out a dog,” Abe said. “Run everything onto you. Then they put the dog killer after you and it crosses out everything. I see how it works,” he said, nodding like that, to himself.

Curley said, “Maybe they will take it far enough back so they can make out it was you all the time, instead of Apaches out here.”

Abe looked at him with his green marbles of eyes. “Do you think you are joking, Curley? They could do it if they tried. Because time was when every foul thing any man did it was Paches did it. And so old Peach came dog-killing down and cleaned them out. And so start all over clean. It is like a woman every month. Now it’s Abe McQuown is the dog and Blaisedell dog killer so they can start clean again. I see how it works.”

“ Jesus!” the old man said.

“Watch I’m not right, Daddy,” Abe said. “They have piled all the foul on me now. Then they will bleed it out and start clean. A man’d been educated he could follow it all the way back through history, I expect. How it’s worked just like that. You can’t blame them. Can’t blame Blaisedell even.”

“ Jesus Christ!” Dad McQuown said. Curley looked at Dechine and shook his head a little, and Dechine found a place on the back of his hand that needed studying more than his knees.

Curley said, “Abe, I guess I never knew a man with as many friends as you. And talking this crazy stuff.”

Abe blinked and stared off at the mountains. After a long time he said, “You think I have gone yellow. But I’m not scared. I just feel like one of those calves in the Bible that’s going to get its throat cut by a bunch of wild Jews set on it. Only those calves never knew what was happening to them.”

“Holy Jesus Christ, son!” the old man yelled. “You have been chewing on the wrong weed. Son—”

But Abe continued, not even raising his voice. “Can’t blame Blaisedell even. He is just doing what all the rest want. He is just the one with the knife to do the cutting.”

Dechine said, “I never heard about Blaisedell being any shakes with a knife.”

Abe’s eyes glittered with anger as he glared at Dechine. But he did not speak, and Curley sighed to see him.

“Son,” the old man said. “Now listen here, son. Why, God-damned right it looks like Blaisedell is itching to kill you. But the thing you have to do is kill him first.”

“He’ll kill me if he gets a chance,” Abe said. “I’d be a fool to give him the chance.”

Curley said slowly, “Blaikie would surely like to buy this spread, Abe.” He met Abe’s eyes that blazed at him, sorrier for Abe than he had ever been for anyone else; Abe’s eyes wavered away from his, and he was sorry for that, too.

“Do you think I would run out like Luke?” Abe said hoarsely.

“What’re you going to do, Abe?” Dechine asked.

“Only one thing for a man to do,” Dad McQuown said, “that’s being chased out of his own country.”

“Wait it out,” Abe said.

“Why, son, there’s them that fought your fight for you moldering on Boot Hill in Warlock! Why, if I was anything but half a man myself I’d—”

“You’re not,” Abe snapped.

Curley said, “I’ve been thinking of moving on myself, Abe.”

“Run then.”

“I wouldn’t look at it I was running. Things have gone bad here, is all. I wouldn’t look at it that you was running either.”

“I don’t run,” Abe said. He shook his head, his face in shadow beneath his hatbrim, the sun red-gold in his beard.

“Or fight,” the old man said contemptuously. “Or anything.”

“Wait it out, that’s the best thing, Abe,” Dechine said. Curley saw Abe’s face twist again, as though with pain, and Curley stood up a little straighter, where he leaned against the rail. He could feel the strangled violence in Abe and he was afraid that if Dechine said one more stupid thing Abe would jump him.

But Abe only shrugged and said, “Can’t go against what everybody thinks of you.” Then, after a time, he said, “Can’t run and I can’t go against him. He is fast. He is faster than anybody in the country. He’s– He’d—”

He stopped, staring, and Curley turned to see the brown dog trotting around the corner of the house, his dark-spotted tongue lolling from his mouth. Abe leaned back stiffly. His hand flicked down, and up; his Colt crashed with a spit of fire and smoke and the dog was knocked rolling in the dirt with about a half a yelp. The Colt crashed and spat again and again, and with each shot the brown, bloody, dusty body was pushed farther away as though it were being jerked along on the end of a rope.

“Like that!” Abe whispered, as the gunsmoke blew away around him. He holstered his Colt. “Like that,” he said again.