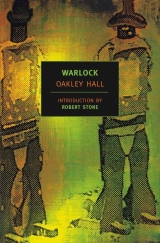

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

“Mine too, by God!” Wash said.

“He ought to be shot down on Billy’s grave, what he ought,” Dad McQuown said. “Billy was a fine boy, and him nothing.”

“I am talking about Curley,” Abe said. He waited, his face a bearded, furrowed mask, his eyes hooded. Then he said, “You ought to be riding in with us, Bud.”

He shook his head.

“But you swore to it, didn’t you?” Abe went on. “You swore Carl told you he’d done it himself, didn’t you? Or did you crawfish on that?”

“Not yet,” he said, and instantly he knew that what he had meant as only a passing threat was too much more than that. He heard the whistling suck of Abe’s breath, and saw Abe’s right eye widen while his left remained a slit.

“What do you think you mean by that?” Abe whispered.

He didn’t answer right away. But he had not, he thought, come here merely so he could get away without trouble. He had come to tell them they must not come into Warlock as Regulators. He said tiredly, “There is going to be peace and law in Warlock, Abe. Or there is going to be Blaisedell. If you will let be, he will go. He knows he has to go now, for he has been wrong.”

“Let him go, then.”

“You will have to let be for him to go. And I will see that you let him be, and Warlock will. I have more ways than deputizing people for stopping you.”

“I am sure scared of that pack of fat-butt bank clerks he is going to round up in there,” Whitby said. “Whoooo! I—”

“Shut up!” Abe snapped. He stared at Gannon with his head tipped forward so that his beard brushed his chest, and his green eyes were wild. “What other ways, Bud?”

“I would crawfish to stop you.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” the old man said. “I can’t make out what—”

“Shut up!” Abe put a hand on top of the stove and leaned on it heavily. “Damn your dirty soul to hell!” he cried. “God damn you, coming down here mealy-mouthing what you are bound to do. I will tell you what you are bound to do! You damned lick-spittle, you will swear here and now to what Carl said to you and what is true!” Abe took a step toward him. “Swear it, damn you!”

“I guess I’ll not—” he started, and tried to dodge as Abe’s hand swung up against his cheek. He staggered sideways with the blow; his cheek burned maddeningly, and his eyes watered. He heard a murmur of approval from the others, whom, for a moment, he could not see.

“Swear it! You will swear to the truth or I’ll kill you!”

He shook his head; he saw the buckskin arm swing again. He did not dodge this time, but only jerked his head back to try to soften the blow. There was pain and the taste of blood in his mouth.

“Hit him all night,” the old man said.

“Cut him, Abe!”

“Say it!” Abe said.

He shook his head, and swallowed salt blood.

“ Say it!”

The fist he hadn’t even seen coming this time exploded in his face once more, and he stumbled back in a wild shouting with the room spinning around him. Abruptly the shouting stopped as he caught his balance, and felt in his hand, with horror, the hard rounded shape of the Colt he had drawn. In his clearing eyes he saw Abe McQuown twisted slightly with his right fist down in the uncompleted recovery of the blow. Abe straightened slowly, his chest heaving in the buckskin shirt as he panted, his left hand massaging the knuckles of the right, his eyes glancing from the Colt to Gannon’s face. A grin made sharp indentations in his beard.

Gannon spat blood. The Colt felt unsupportably heavy in his hand. Abe grinned more widely. “Uh-uh, Bud,” he said, and came a step forward. He came another; his moccasins lisped upon the floor. “Uh-uh, Bud.”

Abe’s hand snapped down over his hand as sharp and tight as a talon, and wrenched the Colt away. Abe flung it to the floor behind him, and laughed. Abe swung his arm again.

He hunched his shoulder up to catch the blow. He brought his right hand up to catch the next on his forearm. With a sudden wild elation he swung back, and his fist met hair and bone. Abe staggered back and he jumped in pursuit.

A foot tripped him. He fell heavily past Abe, who dodged aside. A fist slammed against his back as he caught himself on his hands and tried to scramble up. He cried out in pain as a boot smashed into his ribs, and fell back again. Beneath him he felt the hard shape of his Colt where Abe had dropped it.

He fumbled it free with his left hand, still trying to rise with his right hand braced on the table beside the buggy seat, dodging aside as Whitby aimed another kick at him, and the men on the buggy seat leaped out of the way. Then he had the Colt free and he swung it desperately to cover Cade, who had drawn. He saw only the long flash of the knife blade in the lamplight.

He screamed, frozen half up, with his right hand pinned to the table top by a white-hot shaft.

Whitby kicked the Colt from his left hand.

“Get up!” Abe panted.

He struggled to stand, with his shoulder cocked down so that his hand lay flat upon the table. He could hardly see for the sweat pouring into his eyes. Abe was leaning on the shaft of the knife with both hands, not forcing it down but merely holding it there. “Move and I’ll cut it off, Bud,” he said.

He didn’t move.

“Geld him, son,” the old man said calmly.

Now his hand merely felt numb and the faintness began to leave him. Leaning on the knife still, Abe disengaged his right hand, and, with a careful, measured movement, slapped him, not hard.

“Don’t move, Bud,” Abe said, grinning. The hand slapped his cheek harder. It came again and again, each time harder. The faintness bore down on him again as the knife edge tore his flesh. He felt only the sensation of tearing, rather than the pain. “Don’t move, Bud,” Abe warned, and slapped him. The faintness began to crush him.

“Swear it for us, Bud!”

He shook his head. He could feel the blood beneath his hand now, so that it seemed glued to the table as well as nailed there. “Swear it, damn you to hell!” Abe cried, and there was hysteria in his voice.

“Lever that handle a little, son. Let’s hear him squeak.”

“This isn’t doing any good, for Christ’s sake, Abe!” Chet Haggin said.

“Let me take that knife to him!” Cade said.

Abe pressed downward on the handle, and Gannon closed his eyes. The pressure ceased and he opened them. He could see the shine of spittle at the corners of the mouth in the red beard. He gazed around at the others, dimly pleased that he could stare each one of them down.

“Hold off, Abe!” Chet said.

“Swear it, Bud!” Abe whispered. “Or I swear to God I will cut your hand off! I’ll kill you!”

“You had better kill me if you want to take your Regulators into Warlock,” he said. “For I will stop you otherwise.”

It was a way out if Abe wanted to take it, and he knew Abe did. Abe turned his face in profile, his long jaw set wolfishly and sweat showing on his cheeks. He looked pale. Wash said quickly, “I would surely like to see him trying to stop us!”

“I’d like to see that,” Walt Harrison said.

Abe jerked the knife free, and he gasped as the air got into the wound like another knife. He left his hand on the table to support himself now, as he watched Abe wipe the knife blade on his trouser leg. The old man was muttering.

“Get that neckerchief out and bind that hand up,” Chet said roughly. “There may be some that like the stink of blood, but damned if I do.”

“Kind of surprised to see he’s got any in him,” Whitby said.

Gannon fumbled the cloth from his pocket and tried to bind it around his bleeding hand. Joe Lacey came forward to help him, pulling the bandage tight and tying the ends together.

“Stop us then,” Abe said, in a cold voice. “We’ll be in tomorrow.”

“He’ll just ride back and warn Blaisedell out of town, God damn it, son!” Dad McQuown cried. “I say kill him or hold him down here!”

“Let me settle my account with him, Abe,” Cade said.

McQuown grinned mockingly. “Well, move along, Bud. Before my mind gets changed.”

Gannon looked around for his Colt. “Give it to him,” Abe said. “He can’t do anything with it.”

Walt Harrison handed him the Colt. He took it with his wounded hand. It slipped through his fingers and he caught it by slapping it against his leg. Awkwardly he slid it into his holster. Whitby thrust his hat on his head. He walked slowly through them toward the door. There he turned. Abe was still standing at the table, jabbing the point of his knife into the wood with a kind of listless viciousness.

“I’ve warned you,” Gannon said. “You are not to come into Warlock like you are set to do.” This time no one laughed.

He went outside into the buzzing darkness. Carefully he descended the steps. A dog began to bark, and the others joined in a chorus. They would be locked up, he remembered; they always were when men were coming and going at night.

In the saddle he sat motionless for a time, his eyes closed, his left hand clutching the pommel. One by one, gingerly, he sought to move the fingers of his right hand; his little finger, ring finger, middle finger, trigger finger. He sighed with relief when he realized that nothing had been severed, and swung the reins. Gripping the pommel, sitting stiff, heavy, and unsteady in the saddle, he touched in his spurs and whispered, “Let’s go home, girl.”

The mare mounted the first ridge in the pale moonlight, went down the draw, up the second ridge – he didn’t look back. A falling star crossed the far flank of the sky, fading, as it fell, to nothing. There was a cold wind. He shivered in it, but drew himself up straighter, released his grip on the pommel, and raised a hand to set his hat on straight. Lowering his hand, he brushed his thumb past the star pinned to his jacket, as though to reassure himself he had not lost it.

He felt a fury that was pain like a tooth beginning to ache. He said aloud, “I am the law!” The fury mounted in him. They had insulted him, cursed him, threatened him. They had beaten and stabbed him, and deliberated his death. They had presumed to judge him, and, finally, to release him in contempt of his warning. The fury filled him cleanly, at their presumption and their ignorance.

But how would they know differently? They had never known differently. He had tried to show them courage to make them see. Once, at least, they had known courage and had respected it. Maybe they would simply not respect it in him, or maybe they knew it no longer, knew now only fear and hate and violence. The clean fury drained from him; he had been able to show them nothing. And now he could almost pity Abe McQuown, remembering the desperation he had seen in Abe’s eyes as he leaned upon the knife, Abe fighting and torturing for the Right as though it were something that could be taken by force. For Right had been embodied in Curley’s death, and perhaps Blaisedell was as desperate in his way for Right as McQuown was. But he knew that Blaisedell would not cold-bloodedly kill for it, would not plot to take it by trick or treachery – not yet.

He had been riding for an hour or so in the heavier darkness under the cottonwoods along the river when he heard the shot. It was a faint, flat, far-off sound, but unmistakable. There was a silence then in which even the liquid rattle of the river seemed stilled, and then a ragged volley of shots. After another pause there were two more, and, after them, silence again.

He rode looking back over his shoulder. He could see nothing, hear nothing but the riffling of the river and the wind in the trees, the steady pad of the mare’s hoofs with the occasional crack of shoes against a rock outcrop. Finally he settled himself in the saddle again and into the weary rhythm of the ride back to Warlock, dozing, snapping awake, and dozing again.

Much later he thought he heard, off to the east, the clatter of fast-moving hoofs, but, coming awake with that unpleasant, harsh grasping at consciousness, he could not be sure. Awake, he did not hear it, and he thought the sound must have been only something he had dreamed.

46. JOURNALS OF HENRY HOLMES GOODPASTURE

April 18, 1881

IN VIEW of the importance of this morning’s Citizens’ Committee meeting, I will set down what happened there in some detail.

One of Blaikie’s hands arrived last night with the information that a great number of San Pabloites were gathered at the McQuown ranch, and, with this proof of McQuown’s intentions, all the members of the Citizens’ Committee with whom I spoke prior to the meeting were resigned to the conclusion that we were forced to undertake the formation of a Vigilance Committee at last. Obviously Blaisedell could not be expected to face alone this force of Regulators patently assembled to bring about his destruction, or his flight. The parallel with poor Canning’s fate was all too clear, and we would not be shamed again. Some were eager for war, and some were frightened, but almost all seemed firm in their resolve to back Blaisedell to the hilt.

The meeting was at the bank. All but Taliaferro attended: Dr. Wagner, Slavin, Skinner, Judge Holloway, Hart, Winters, MacDonald, Godbold, Pugh, Rolfe, Petrix, Kennon, Brown, Robinson, Egan, Swartze, Miss Jessie Marlow, and myself. And Clay Blaisedell, not a member, but our instrument.

The Marshal has not been looking well lately. Yet he seemed himself again in Petrix’s bank, as though he had recovered from an illness, and he had an air of ease and confidence about him that reassured us all. He did not, however, join us at the table – usually he sits to the right of Miss Jessie when she attends – but remained standing outside the counter while Petrix brought the meeting to order.

Jed Rolfe stated the premise: that we had, many times in the past, rejected the idea of a Vigilance Committee, but now, in his opinion, it was unavoidable.

Pike Skinner moved that a Vigilance Committee be established, he was seconded by Kennon, and the meeting was thrown open to discussion.

The doctor rose to state that it was obvious that the true mission of the Regulators was to punish, murder, or drive from Warlock the leaders of the Medusa strike; this had been their original purpose and was still their purpose, although now they saw that the Marshal would have to be disposed of before they could accomplish it, since he would most certainly stand in their way. MacDonald replied that the Regulators had been originally engaged to defend mine property, but that they were no longer in his employ, that he had no understanding with them whatsoever, nor did he hold patent to the title of Regulators. MacDonald then claimed, in his turn, that the doctor was responsible for a miners’ conspiracy against him, MacDonald, and was responsible for an outrageous and threatening set of terms upon which, a delegation of strikers had informed him, they would end the strike.

The doctor responded to this violently, and it was with some difficulty that Petrix restored order. Blaisedell was asked if he wished to speak, but he replied that he would rather hear us out before he expressed his own sentiments.

Will Hart obtained the floor and said with great seriousness that he knew what he was about to say would be unpopular, but that he must, in all honesty, speak out. He felt, he said, that it was the duty of the Citizens’ Committee to prevent bloodshed and not to form Vigilante Committees. The whole system of posting had, in his opinion, proved a failure, and had only led to the bloodshed it had been intended to prevent. He felt strongly that a battle with the Regulators should be avoided if it was humanly possible. This could be accomplished, although he was sorry to be the one to suggest such a thing, by Blaisedell quitting Warlock. The Regulators could then be sent word of this, and they would be deprived of their purpose, which now they could endow with a certain degree of righteousness.

He was afraid, he went on rather nervously, that this might be interpreted as cowardice on Blaisedell’s part. He, of course, knew that Blaisedell had no fear of McQuown – quite the opposite. As for himself, he would regard it as a much greater, and nobler, courage upon Blaisedell’s part were he to go and leave us in peace.

There was an instantaneous and outraged protest to this on every side. Miss Jessie cried out that Will wanted to drive Blaisedell out, and berated him with a violence that embarrassed us all. “After what he has done for Warlock!” she cried. “For everyone here! When all of us used to be afraid of being murdered on the street by a drunken Cowboy, and you speak of his leaving us in peace!” and so forth. She was out of order, but Petrix, usually the strictest of parliamentarians, was too dumbfounded to call her to order. She desisted only when Blaisedell called her name, and the doctor spoke quietly to her.

Jared Robinson stated loudly that he considered Will Hart’s idea a bad one and in bad taste, and that the rest of us apologized to Blaisedell for it. If Blaisedell departed, he said, Warlock would be thrown into chaos again, McQuown would be in the saddle, and any here who had been friendly with Blaisedell – and especially we of the Citizens’ Committee – would be in deadly danger. Succeeding speakers agreed with, and expanded upon, this, until MacDonald reiterated his former statement within this context: that chaos had already descended upon us, and had done so as soon as Blaisedell had permitted the miners to overrun him at the jail, in the attempt to lynch Morgan.

Miss Jessie promptly called him a liar, to which rebuke MacDonald knew better than to retort, although he was plainly infuriated by it. The doctor then said, with what was obviously a stern attempt to control his temper, that it took considerably more of a man to let himself be overrun by momentarily crazed (and with good reason, he added) creatures, than to fire among them as MacDonald no doubt would have preferred. But, he pointed out, Blaisedell, at the time of the attempt on Morgan’s life, had not been in our employ with the status of Marshal, and in any case, his object, which had been to save Morgan from a lynching rather than to preserve his own dignity, had been accomplished.

Judge Holloway, who had been sitting in a gloomy and alcoholic trance, now seemed to have accumulated enough strength to deliver one of his harangues. He rose, was recognized, and beat his crutch upon the floor for silence. He clung to the edge of the table, as fierce of mien (and as noisome of breath) as a vulture, and glared about him. He can be awesome enough, even when falling down drunk. He called us fools and said there was a man to deal with the present situation and it was not Blaisedell. There was a sheriff’s deputy in Warlock to uphold the law. There were, he said, always bloodthirsty fools to cry for a Vigilance Committee or a hired Vigilante, but Deputy Gannon was the one to deal with the Regulators.

His voice was drowned in a sudden burst of speculation as to Gannon’s whereabouts, and condemnation of him. Some thought him fled, some still in Bright’s City (as I did), others claimed he had gone to join McQuown’s forces. Pike Skinner informed us that Gannon had indeed gone to San Pablo, but with the announced intention of warning McQuown that he was not to come into Warlock; at which there were hoots of disbelief.

When order was restored, the Judge reiterated that the situation was the Deputy’s responsibility. Then, as is his custom, he began to rack us for our sins and presumptions. He accused us of inciting Blaisedell to the murder of an innocent man – to our considerable discomfiture, with Blaisedell present; he called us fools and mortal fools, idiots and monstrous idiots. He shouted down, in his wrath, all interruptions, and was, in short, magnificent in his fashion. I think I might have applauded him had not what he was saying been so painful.

He said to us, more temperately, that if we had not been blind we might have seen that we had almost had a man in Carl Schroeder, and that we unmistakably had one now, in Gannon. He expounded with painful sarcasm the complete illegality of Blaisedell’s position as Marshal, a point all too sore with the Citizens’ Committee. Not one of us had the temerity even to glance Blaisedell’s way while this diatribe continued, but at last Miss Jessie jumped to her feet and cried that he was no more a real Judge than Blaisedell was a real Marshal, and that he was a hypocrite to speak as he had.

The Judge replied that he was well aware of the fact that he was a hypocrite, and that he considered himself something worse than that for even belonging to the Citizens’ Committee. He added, “But I do not presume to send men to hang, Miss Jessie Marlow.”

Then, as Miss Jessie started to speak again, he gave her an awkward but courtly bow and said he refused to listen to her, for she was a special pleader, as everyone knew; and, finally, with the look of a man who has collected his courage to approach a rattlesnake, he turned to Blaisedell himself.

The Judge addressed Blaisedell deferentially at first, saying he had intended nothing personal by his remarks, and that his criticism was not so much of Blaisedell as of all of us. Soon, however, he recovered his hectoring style, and he raised his voice, lifted his crutch and shook it, and cried that Blaisedell was a crutch like the one he held, had been useful, and we should be grateful to him. But it was only an idiot who continued to use a crutch when the limb had grown whole. Including us all in his glare, he informed us that we no longer needed the crutch of an illegal gunman, that we had better begin properly using the law or it would wither away, and now we had a man to uphold the law, who was the deputy.

Petrix asked Blaisedell, who had been showing signs of wishing to speak, if he desired the floor. Blaisedell replied that he would like to answer some of the things the Judge had had to say. As he spoke I saw Miss Jessie watching him with her great eyes, tugging a little handkerchief between her hands, and if ever I saw a woman’s heart in her eyes I saw it then.

Blaisedell’s face was very stern as he proceeded upon a track that surprised us. He said that he thought it would be a shame to put too much on the Deputy too soon. He said a new horse should not be racked too hard. “You will bust him to running, or kill him, putting too much on him,” he said, to the Judge. And he said, “He has stood up to every man here calling him a liar when he was not, but I don’t think he is able yet to stand off a wild bunch from San Pablo.”

He went on in this vein. But after we had grasped the fact that he believed that Gannon had not lied, and seemed to favor him – even though he did not feel he was qualified to stop McQuown yet – our comprehension of what he was saying ceased and we stared at him in confusion. I saw Buck Slavin’s jaw hanging open like that of a dull-witted boy, and Pike Skinner’s face grow fiery red. Miss Jessie had put her handkerchief to her mouth, and her eyes were round as dollars.

“Gentlemen,” Blaisedell said. “I have done some service here and I think you know it. But I think a good many of you are beginning to wish I would move along, and not just Mr. Hart.” He smiled a little then. “I had better, before you all start thinking of me like the Judge here does.”

Skinner and Sam Brown protested emotionally, as did Buck, but Blaisedell only smiled and went on to thank the Citizens’ Committee for having paid him well, and backed him as well as he could have wished. “But,” he said, “there is value in knowing when to move on. For the Judge is right in more ways than one, though I have argued with him and got as mad at him as the rest of you do.”

Blaisedell said, however, that he had one thing which he would ask of us. “I will ask you to let me handle McQuown and his Regulators my own way.” He said this in such a way that it was clearly a command for us to stay out of his affair. “It is my job,” he went on. “And he is coming after me, so it is my job two ways. If there are going to be Vigilantes I’ll ask that they stay out of it unless Igo down.” He looked straight at MacDonald and said, “For I have been known to go down.”

There was a general gasp as it was realized that Blaisedell meant to stand alone, or perhaps only with Morgan, against the San Pabloites. A storm of exclamations and protests broke out, to which Blaisedell did not even attempt to reply, while Petrix exercised his gavel violently.

It was at this moment that Gannon made his entrance. He was freshly shaven, his hair neatly combed, but his upper lip was bruised and swollen and his face was drawn with exhaustion. I noticed that his right hand was bound up in a white cloth. He said, in a truculent tone, that there would be no Vigilantes in Warlock.

We were all as shocked at the arrogance of his first words as we had been at the implication of Blaisedell’s last ones. I had the impression, however, that Gannon had been steeling and rehearsing himself to his statement for some time, and was prepared, too, for a violent response to it. When there was none he seemed suddenly timid in our august presence.

In a more reasonable voice he said that he was sorry to butt in upon us, but that he had heard the Citizens’ Committee intended to form a Vigilante Troop, and he had come to inform us that there would be none of that in Warlock.

Jed Rolfe asked him if those had been his orders from McQuown.

Gannon replied without heat that he did not take orders from McQuown. Neither did he take them from the Citizens’ Committee. He had just come back from San Pablo, he said, whence he had ridden to tell McQuown there would be no Regulators. He was now telling us there would be no Vigilantes either. I felt a certain respect for the fellow then, thinking that he must not have pleased McQuown any more than he was pleasing us.

Skinner sneered that he would bet Gannon had scared McQuown out of his foolishness, and it was certainly nice that Warlock, and Blaisedell, had nothing to worry about. At this Gannon looked childishly angered and hurt. He said, however, that if McQuown did come in he would deputize whoever was needed to meet him, and reiterated his statement that there were to be no Vigilantes. I noticed that he studiously avoided Blaisedell’s eye.

Joe Kennon cried out that no one trusted Gannon enough to be deputized by him, to which Gannon replied that whoever he deputized would be deputized or go to Bright’s City to explain why not to the court. This exchange was followed by other angry statements, until Blaisedell interceded to say that it was his part to make a play against McQuown and whoever came in with him. “It is against me,” he said. “So it is me against them, Deputy.”

He spoke in a firm voice, and Gannon blanched noticeably. He stood still not facing Blaisedell, with his bandaged hand upon the counter and his forehead creased with what must have been painful thought. To our surprise he shook his head with determination.

“If it was just you against McQuown, I would keep out, Marshal,” he said. “I can’t when it is the whole bunch coming in and calling themselves Regulators.”

“Yes, you can,” Blaisedell said. It did not seem to me he said it particularly threateningly, but he drew himself up to his full height as he looked down at the Deputy.

Gannon, however, stood his ground. He said in an emotional voice, “I have told McQuown he is not to come in here with those people. I told him I will stop him if he does. I mean to stop them.”

With that he swung around to depart, and, although we waited breathlessly for Blaisedell’s reply, he made none. It was the Judge who broke the silence. “Hear! Hear!” he cried, in obnoxious triumph. His voice was drowned in the ensuing outcry, and Gannon was verbally flayed, drawn and quartered, and otherwise disposed of.

In the end, however, nothing was done about the Vigilance Committee.

April 19, 1881

I will confess that for a time I subscribed to a higher opinion of our Deputy than I had previously held. That was yesterday. Today the mercury of my esteem has sunk quite out of sight, for Gannon, in claiming he would stop McQuown from coming into Warlock, has perpetrated one of the most monstrous, grotesque, and completely senseless frauds of which I have ever heard.

Gannon is, in short, accused of murder. McQuown will not bring his Regulators into Warlock because he is dead, shot in the back, and Gannon is named by a host of witnesses as his murderer.

The Regulators have, indeed, arrived, but not in that role. They are pall-bearers, and Abraham McQuown is their charge. The story I have from Joe Lacey, who swears he was witness to it all.

As he informed the Citizens’ Committee yesterday, Gannon had ridden down to San Pablo the night before. He accosted the Regulators, who were gathered at McQuown’s, with the same brusquerie he showed the Citizens’ Committee at the bank. Hot words passed, and shortly, Lacey claims, Gannon drew his six-shooter on McQuown. Here I become a little dubious as to whether I am hearing the whole story, since drawing upon McQuown in the bosom of his friends sounds an act of incredible asininity. Be that as it may, McQuown then closed and tussled with Gannon, and, defending himself, stabbed Gannon through the hand, which accounts for the bandage we saw yesterday. Gannon was then allowed to depart, which he did ungraciously, calling back that he and Blaisedell would “get even.”

Lacey claims he thought Gannon might still be skulking about, for the dogs, which were locked up, had started barking when he first left the ranch house and were never entirely quiet thereafter, as though sensing a sinister presence. About an hour later the door was flung open and Gannon fired upon McQuown, who was standing with his back to the door, killing him instantly. He then fled, but not before he was recognized by old Ike McQuown, Whitby, and several others.

All crowded outside to fire after him in his flight, but pursuit was impossible, for he had unhitched the horses and these were stampeded by the shooting. By the time the mounts were recovered it was clearly useless to try to follow him, and some were afraid that Gannon had been accompanied by a whole party of murderers from Warlock, and that he desired to be pursued so that he could lead the Cowboys into an ambush. There is no doubt in Lacey’s mind that Gannon was the assassin, for, although he did not see him himself, a number of others did.