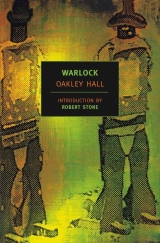

Текст книги "Warlock"

Автор книги: Oakley Hall

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 32 (всего у книги 40 страниц)

I

SITTING in the cane-bottomed rocker in the shade on the hotel veranda, Morgan sat watching Warlock in the morning. There were not many people on the street: a prospector with a beard like a bird’s nest sat on the bench before the Assay Office; a white-aproned barkeep swept the boardwalk before the Billiard Parlor; a Cross-Bit wagon was pulled up alongside the Feed and Grain Barn, and Wheeler and a Mexican carried out plump bags which one of Burbage’s sons stacked into the wagon-bed. To the southwest the Dinosaurs shimmered in the sun. They seemed very close in the clear air, but improbably jagged and the shadows sharply cut, so that they had a painted look, like a fanciful theater backdrop. The Bucksaws, nearer, were smooth and brown, and he watched a wagon train mounting the circuitous road to the Sister Fan mine.

He stretched hugely, sighed hugely. Inside the dining room behind him he could hear the tinny clink and clatter of dishes and cutlery; it was a pleasant sound. He watched Mrs. Egan bustling down Broadway with her market basket, neat and crisp in starched light-blue gingham, her face hidden in a scoop bonnet. He could tell from the way she carried herself that she was daring any man to make a remark to her.

He smiled, strangely moved by the fresh, light color of her dress. He had found himself thus susceptible to colors for the last several days. He had admired the smooth, dark, smoked tan of the burnt-out Glass Slipper yesterday, and the velvet sudden black of the charred timbers in it. Now on the faded front of the Billiard Parlor, where Sam Brown had taken his sign down to have it repainted, there was a rectangle of yellow where the paint had been hidden from the sun; yellow was a fine color. He had begun remembering colors, too; in his mind’s eye he could see very vividly the color of the grass in the meadows of North Carolina, and the variety of colors of the trees in autumn – a thousand different shades; he remembered, too, the trees in Louisiana, the sleek, warm, blackish, glistening green of the trunks after it had rained and the sun had come out; and the trees in Wyoming after an ice storm in the sun, when all the world was made of crystal, and all seemed fragile and still; and he remembered the sudden red slashes of earth in west Texas where the dull plains began to turn into desert country.

“Pardon me if I take this other chair here, sir.” It was the drummer who had come to town yesterday, and had the room across the hall from his. He sat down. He wore a hard-hat, and a tight, cheap, checked suit. He was smooth-shaven, with heavy, pink dewlaps.

“Fine morning,” the drummer said heartily, and offered him a cigar, which he took, smelled, and flung out into the dust of the street. He took one of his own from his breast pocket, and turned and stared the drummer in the eye until he lit it for him.

“I wonder if you could point out Blaisedell for me, if he comes by,” the drummer said, not so heartily. “I’ve never been in Warlock before and we’ve heard so much of Blaisedell. I swore to Sally – that’s my wife – I’d be sure I saw Blaisedell so I could tell her—”

“Blaisedell?”

“Yes, sir, the gunman,” the drummer said. He lisped a little. “The fellow that runs things here. That killed all those outlaws in the corral there by the stage depot. I stopped in there yesterday when I got in for a look around.”

“Blaisedell doesn’t run things here.” He stared the drummer in the eye again. “ Ido.”

The drummer looked as though he were sucking on the inside of his mouth.

“You can tell your wife Sally you saw Tom Morgan,” he said. He felt pleased, watching the fright in the drummer’s face, but his stomach contracted almost in a cramp. He flicked his cigar toward the drummer’s checked trousers. “Don’t go around here saying Clay Blaisedell runs Warlock.”

“Yes, sir,” the drummer whispered.

The water wagon passed on Broadway, Bacon sitting hunched on the seat, his whip nodding over the team. The rust on the tank shone red with spilled water. The red of rust was a fine color. When the water wagon had passed he saw Gannon coming toward him under the arcade.

“Get out of here,” he said to the drummer. “Here comes another one that thinks he runs Warlock.”

The drummer rose and fled; Morgan laughed to hear the clatter of his boots diminishing, watching Gannon coming on across Broadway. The sun caught the star on his vest in a momentarily brilliant shard of light. He came on up on the veranda and sat down in the chair the drummer had vacated.

“Morning, Morgan,” he said, and nervously rubbed his bandaged hand upon his leg.

“Is, isn’t it?” He crossed his legs and yawned.

Gannon was frowning. “Going to be hot,” he said, as though he had just thought it out.

“Good bet.” He nodded and looked sideways at Gannon’s lean, strained face, his bent nose and hollow cheeks. He touched a finger gently to his own cheek, waiting for Gannon to get his nerve up.

“I’ve found two of them saw you coming back,” Gannon said finally, “the morning after McQuown was killed.”

He didn’t say anything. He flicked the gray ash from his cigar.

“I heard you when you went by me,” Gannon said, staring straight ahead. “Off to the east of me a way. I couldn’t say I saw you, though.”

“No?”

“I’d like to know why you did it,” Gannon said, almost as though he were asking a favor.

“Did what?”

Gannon sighed, grimaced, rubbed the palm of his hand on his leg. The butt of his Colt hung out, lop-eared, past the seat of his chair; if he wanted to draw it he would have to fight the chair like a boa constrictor. “I think I know why,” he went on. “But it would sound pretty silly in court.”

“Just leave it alone, Deputy,” Morgan said gently.

Gannon looked at him. One of his eyes was larger than the other, or, rather, differently shaped, and his nose looked like something that had been chewed out of hard wood with a dull knife. It was, in fact, very like the face of one of those rude Christoscarved by a Mexican Indio with more passion than talent. It was a face only a mother could love, or Kate.

“Deputy,” he said. “You don’t hold any cards. You found two men that saw me riding into town, but I know, and you know, that as much as those people down the valley would be pleased if it turned out I had shot McQuown, they have jerked the carpet out from underneath it by all of them swearing up and down it was you that did it. They can’t do anything but make damned fools of themselves, and you can’t. So just sit back out of the game and rest while the people that have the cards play this one out. It is none of your business.”

“It is my business,” Gannon said.

“It is not. It’s something so far off from you you will only hear it go by. Off to the east a way. You probably won’t even hear it.”

They sat in silence for a while. He rocked. Finally Gannon said, “You leaving here, Morgan?”

He gazed at the bright yellow patch over the Billiard Parlor. “One of these days,” he said. “A few things to tend to first. Like seeing to a thing for Kate.”

He waited, but Gannon didn’t ask what it was, which was polite of him. So he said, “She thinks you are about to choose Clay out. I promised I’d watch over you like a baby.”

Gannon cleared his throat. “Why would you do that?”

Why, for one thing, he thought, because I saw you get that hand punctured by a hammer pin one night; but aloud he said, “You mean why would I do it for her?” He turned and looked Gannon in the eye. “Because she was mine for about six years. All mine, except what I rented out sometimes.” He was ashamed of saying it, and then he was angry at himself as he saw Gannon’s eyes narrow as though he had caught on to something.

“That’s no reason,” Gannon said calmly. “Though it might be a reason for you to kill Cletus.”

It shook him that Kate should have told her deputy. Or maybe she hadn’t, since it was something anybody could pick up at the French Palace, along with a dose. “That wasn’t in your territory, Deputy,” he said. “Leave that alone too.”

Gannon looked puzzled, and Morgan realized he had been speaking of Pat Cletus. He felt a stirring of anxiety, and he thought he had better set Gannon back on his haunches. He stretched and said, “Are you going to make an honest woman of Kate, Deputy?”

Gannon’s face turned boiled red.

“Morgan grinned. “Why, fine,” he said. “I’ll sign over all rights to you, surface and mining. And give the bride away too. Or don’t you want me to stay that long?”

Gannon turned away. “No,” he said. “I don’t want you to stay, since you asked.”

“Running me out?”

“No, but if you don’t get out I will have to take this I came to ask you about as far as it goes.”

“And you don’t want to do that.”

“I don’t want to, no,” Gannon said, shaking his head. “And like you say I don’t expect I’ll get much of anywhere. But I will have to go after it.”

“You could leave it alone, Deputy,” he said. “Just stand back out of the way awhile. Things will happen and things will come to pass, and none of it concerns you or much of anybody else. I will be going in my own time.”

Gannon got to his feet, splinter-thin and a little bent-shouldered. “A couple of days?” Gannon said doggedly.

“In my own good time.”

Gannon started away.

“Don’t post me out of town, Deputy,” Morgan whispered. “That’s not for youto do.”

He regarded what he had just said. He had not even thought of it before he had said it; or maybe he had, and had just decided it.

But it was the answer, wasn’t it? he thought excitedly. And maybe he could still keep the cake intact, and let the others think they saw crumbs and icing all over Clay’s face. He began to check it through, calculating it as though it were a poker hand whose contents he knew, but which was held by an opponent who did not play by the same rules he did, or even the same game.

II

Later he sat waiting for Clay at a table near the door of the Lucky Dollar. He watched the thin slants of sun that fell in through the louvre doors, destroyed, each time a man entered or departed, in a confusion of shifting, jumbled light and shadow as the doors swung and reswung in decreasing arcs. Then they would stand stationary again, and the barred pattern of light would reform. During the afternoon the light would creep farther in over Taliaferro’s oiled wood floor, and finally would die out as the sun went down, and another day gone.

He did not think he would do more today than test the water with his foot, to see how cold it was.

The pattern of light was broken again; he glanced up and nodded to Buck Slavin, who had come in. Slavin nodded back, hostilely. Look out, he thought, with contempt; I will turn you to stone. “Afternoon,” Slavin said, and went on down the bar. Look out, I will corrupt you if you even speak to me. He could see the faces of the men along the bar watching him in the glass; he could feel the hate like dust itching beneath his collar. From time to time Taliaferro would appear from his office – to see if he had begun to ride the faro game yet, and Haskins, the half-breed pistolero from the French Palace, watched him from the bar, in profile to him, with his thin mustache and the scar across his brown chin like a shoemaker’s seam, his Colt thrust into his belt.

He nodded with exaggerated courtesy to Haskins, poured a little more whisky in his glass, and sipped it as he watched the patterns of light. He heard the rumble of hoofs and wheels in the street as a freighter rolled by, the whip-cracks and shouts. The sun strips showed milky with dust.

Clay came in and his bowels turned coldly upon themselves. He pushed out the chair beside him with a foot and Clay sat down. The bartender came around the end of the bar in a hurry with another glass. Morgan poured whisky into Clay’s glass and lifted his own, watching Clay’s face, which was grave. “How?” he said.

“How,” Clay said, and nodded and drank. Clay grinned a little, as though he thought it was the thing to do, and then glanced around the Lucky Dollar. Morgan saw the faces in the mirror turn away. He listened to the quiet, multiple click of chips. “It is quiet these days,” Clay said.

Morgan nodded and said, “Dull with McQuown dead.” He supposed Clay knew, although there was no way of telling. Clay was turning his glass in his hands; the bottom made a small scraping sound on the table top.

“Yes,” Clay said, and did not look at him.

“Look at scarface over there,” he said. “Lew can’t make up his mind whether to throw him at me or not.”

Clay looked, and Haskins saw him looking. His brown face turned red.

“Before I go after Lew,” Morgan said.

“I asked you to leave that alone, Morg.”

He sighed. “Well, it is hard when a son of a bitch burns your place down. And hard to see the jacks so pleased because they think one of them did it.”

Clay chuckled.

Well, he had backed off that, he thought. He said, “I saw Kate last night. She is gone on that deputy – Kate and her damned puppy-dogs. This one kind of reminds me of Cletus, too.”

“I don’t see it,” Clay said.

“Just the way it sets up, I guess it is.”

Clay’s face darkened. “I guess I don’t know what you mean, Morg. It seems like a lot lately I don’t know what you are talking about. What’s the matter, Morg?”

I have got a belly ache, he observed to himself, and my feet are freezing off besides. He did not think that he could do it now. “Why, I get to thinking back on things that have happened,” he said. “Sitting around without much to do. I guess I talk about things without letting the other fellow in on what I’ve been thinking.”

He leaned back easily. “For instance, I was just remembering way back about that old Tejanoin Fort James I skinned in a poker game. Won all his clothes, and there he was, stamping around town in his lousy, dirty long-handles with his shell belt and his boots on – he wouldn’t put those in the pot. Remember that? I forget his name.”

“Hurst,” Clay said.

“Hurst. The sheriff got on him about going around that way. ‘Indecent!’ he yelled. ‘Why, shurf, I’ve been sewed inside these old long-johns for three years now and I’m not even sure I have got any skin underneath. Or I’d had them in the pot too, and then where’d we be?’

“Remember that?” he said, and laughed, and it hurt him to see Clay laughing with him. “Remember that?” he said again. “I was thinking about that. And how people get sewed up into things even lousier and dirtier than those long-handles of Hurst’s.”

He went on hurriedly, before Clay could speak. “And I was remembering back of that to that time in Grand Fork when those stranglers had me. They had me in a hotel room with a guard while they were trying to catch George Diamond and hang him with me. Kate splashed a can of kerosene around in the back and lit up, and came running upstairs yelling fire and got everybody milling and running down to see, and then she laid a little derringer of hers on the vigilante watching me. She got me out of that one. Like you did here, you and Jessie Marlow. I have never liked the idea of getting hung, and I owe Kate one, and you and Miss Jessie one.”

“What is this talk of owing?” Clay said roughly. He poured himself more whisky. “You can take it the other way too, Morg – that time Hynes and those got the drop on me. But I hadn’t thought there was any owing between us.”

No? he thought. It would have pleased him once to know that there was no owing between them; it did not please him now, for debts could be canceled, but if there were no debts then nothing could be canceled at all.

“Why, there are things owed,” he said slowly. And then he said, “I mean to Kate.”

Clay’s cheeks turned hectically red. Clay said in an uncertain voice, “Morg, I used to feel like I knew you. But I don’t know you now. What—”

“I meant about the deputy,” he said. He could not do it. “She is scared,” he said, and despised himself. “She is scared you and the deputy are going to come to it.”

“Is that what you have been working around to asking me?”

“I’m not asking you. I’m just telling you what Kate asked me.”

“There is going to be no trouble between the deputy and me,” Clay said stiffly. “You can tell Kate that.”

“I already told her that.”

Clay nodded; the color faded from his cheeks. The flat line of his mouth bent a little. “Foolishness,” he said.

“Foolishness,” Morgan agreed. “My, I have a time saying anything straight out, don’t I?”

Clay’s face relaxed. He finished the whisky in his glass. Then he said abruptly, “Jessie and me are getting married, Morg. If you are staying maybe you would stand up for me?”

It seemed to him it had been a long time coming, what he knew was coming. But he would not stand up for Clay this time. “When?” he said.

“Why, in about a week, she said. I have to get a preacher down from Bright’s City.”

“I guess I won’t be staying that long.”

“Won’t you?” Clay said, and he sounded disappointed.

He could not stay and stand up for Clay, and give the proper wedding gift to him and to his bride; not both. “No, I guess I can’t wait,” he said. “You will be married half a dozen times before you are through – a wonder like you. I will stand up for you at one of the others. Besides, there’s an old saying – gain a wife and lose your friend. What a man I used to travel with said. He said he had been married twice and it was the same both times. First wife ran off with his partner, and number two got him worked into a fuss with another one – shot him and had to make tracks himself.”

Clay was looking the other way. “I know she is not your kind of woman, Morg. But I’ll ask you to like her because I do.”

“I admire the lady!” he protested. “It is not every man that gets a crack at a real angel. It’s fine, Clay,” he said. “She is quite a lady.”

“She is a lady. I guess I have never known one like her before.”

“Not many like her. She is one to make the most of a man.”

“I’m sorry you can’t stay to stand for me.”

“Not in Warlock,” he said. “I’m sorry too, Clay.” He wondered what Clay thought he wanted, married to Miss Jessie Marlow – to be some kind of solid citizen, with all the marshaling and killing behind him and his guns locked away in a trunk? He wondered if Clay knew Miss Jessie would not allow it, or, if she would, that the others would not. And what was he, Clay’s friend, going to do? I will put you far enough ahead of the game, Clay, so you can quit, he thought. I can do that, and I will do it yet.

“Morg,” Clay said, looking at him and frowning. “What got into you just now?”

Morgan picked up his glass with almost frantic hurry. “How!” he said loudly, and grinned like an idiot at his friend. “We had better drink to love and marriage, Clay. I almost forgot.”

Grief gnawed behind his eyes and clawed in his throat as he watched Clay’s face turned reserved and sad. Clay nodded in acceptance and grasped his own glass. “How, Morg,” he said.

III

When he returned to his room at the hotel it was like walking into a furnace. He threw the window up and opened the door to try to get a breeze to blow the heat out. He had started to strip off his coat when Ben Gough, the clerk, appeared.

“Some miner just brought this by and wanted to know was you here.” Gough handed him a small envelope and departed. The envelope smelled of sachet, and was addressed in a thin, spidery script: Mr. Thomas Morgan. He tore open the flap and read the note inside.

June 1, 1881

Dear Mr. Morgan,

Will you please meet me as soon as possible in the little corral in back of “The General Peach,” to discuss a matter of great importance.

Jessie Marlow

He put his coat back on, and the note in his pocket. He was pleased that she had sent for him – the Angel of Warlock summoning the Black Rattlesnake of Warlock. Probably she would tell him that what she wanted for a wedding present was his departure.

He went outside, across Main Street, and down Broadway. The sun burned his shoulders through his coat. It was the hottest day yet, and it showed no signs of cooling off now in the late afternoon. There were a number of puffy, ragged-edged clouds to the east over the Bucksaws, some with gray bottoms. When he reached the corner of Medusa Street he saw that one was fastened to the brown slopes by a gray membrane. It was rain, he thought, in amazement. He walked on down past the carpinteríaand turned in the rutted tracks that led to the rear of the General Peach.

There was a small corral there, roofed with red tile. He entered, removing his hat and striking a cobweb aside with it. There was a loud, metallic drone of flies. The June-bride-to-be was sitting on a bale of straw, wearing a black skirt, a white schoolgirl’s blouse, and a black neckerchief. She sat primly, with her hands in her lap and her feet close together, her pale, big-eyed, triangular face shining with perspiration.

“It was good of you to come, Mr. Morgan.”

“I was pleased to be summoned, Miss Marlow.” He moved toward her and propped a boot on the bale upon which she sat; she was a little afraid he would get too close, he saw. “What can I do for you, ma’am?”

“For Clay.”

“For Clay,” he said, and nodded. “My, it is hot, isn’t it? The kind of day where you think what is there to stop it from just getting hotter and hotter? Till we start stewing in our own blood and end up like burnt bacon.” He fanned himself with his hat, and saw the ends of her hair moving in the breeze he had created. “Clay has told me you are being married,” he said. “I certainly wish you every happiness, Miss Marlow.”

“Thank you, Mr. Morgan.” She smiled at him, but severely, as though he were to be pardoned for changing the subject since he was observing the amenities. Each time he talked to her she seemed to him a slightly different person; this time she reminded him of his Aunt Eleanor, who had been strict about manners among gentlefolk.

“Mr. Morgan, I am very disturbed by some talk that I have heard.”

“What can that be, Miss Marlow?”

“You are suspected of murdering McQuown,” she said, staring at him with her great, deep-set eyes. He saw in them how she had steeled herself to this.

“Am I?” he said.

He watched her maiden-aunt pose shatter. “Don’t—” she said shakily. “Don’t you see how terrible that is for Clay?”

“There is always talk going around Warlock.”

“Oh, you must see!” she cried. “Don’t you see that it is bad enough that people should think he had something to do with your going down there and – and – Well, and even worse, that—”

“Why, I don’t know about that, Miss Marlow. I am inclined to think that whoever killed McQuown did Clay a favor. And you.”

“That is a terrible thing to say!”

“Is it? Well, Clay might be terrible dead otherwise.”

She opened her mouth as though to cry out again, but she did not. She closed it like a fish with a mouthful to mull on. He nodded to her. “McQuown was coming in here with everything Clay would have had a hard time turning a hand against. I don’t mean a bunch of cowboys dressed up to be Regulators, either. I mean Billy Gannon and most of all I mean Curley Burne.”

“They were dead,” she whispered, but she flinched back as he stared at her and he knew he had been right about Curley Burne.

“Dead pure as driven snow,” he said. “Curley Burne, that is, and Billy Gannon not quite so pure but maybe pure enough because of the talk going around Warlock. McQuown was coming in with that and he could have come alone, only he didn’t know enough to see it. Clay would have been running yet. But since he wasn’t coming alone Clay didn’t have to run, and he may be the greatest nonesuch wonder gunman of all time but he wouldn’t have lasted the front end of a minute against that crew. The man who shot McQuown did him a favor. And you.”

He heard her draw a deep breath. “Then you did kill McQuown,” she said, and now she was severe again, as though she had gotten back on track.

He shrugged. Sweat stung in his eyes.

“Well, that is past,” she said, in a stilted, girlishly high voice. “It cannot be undone. But I hope I can persuade you—” Her voice ran down and stopped; it was as though she had memorized what she was going to say to him in advance, and now she realized it did not follow properly.

“What do you want, Miss Marlow?”

She didn’t answer.

“What do you want of him?” he said. “I think you want to make a stone statue of him.”

She looked down at her hands clasped in her lap. “You cannot think me strange if I want everyone to think as highly of him as I do.”

It was fair enough, he thought. It was more than that. She had cut the ground right out from beneath him with the first genuine thing she had said. She smiled up at him. “We are on the same side, aren’t we, Mr. Morgan?”

“I don’t know.”

“We are!” Still she smiled, and her eyes looked alight. She was not so plain as he had thought, but she was a curious piece, with her face not so young as the dress she affected and the style of her hair. But her eyes were young. Maybe he could understand why Clay was taken with her.

“What if we are?”

“Mr. Morgan, you must know what people think of you. Whether it is just or not. And don’t you see—”

He broke in. “People don’t think as highly of him as they should. Because of me.”

“Yes,” she said firmly, as though at last they had come to terms and understood one another. “And everyone is too ready to criticize him,” she went on. “Condemn him, I mean. For men are jealous of him. Too many of them see him as what they should be. I don’t mean bad men – I–I mean little men. Like the deputy. Ugly, weak, cowardly little men – they have to see all their own weaknesses when they see him, and they are jealous – and spiteful.” She was breathing rapidly, staring down at her clasped hands. Then she said, “Maybe I understand what you meant when you implied he would have been helpless against McQuown, Mr. Morgan. But he is helpless against the deputy, too, because you killed McQuown for him, and the deputy is in the right pursuing it.”

Her eyes shone more brightly now. There were tears there, and he turned his face away. He had thought he could be contemptuous of her because of the different poses she affected – the faded lady, the maiden aunt, the innocent schoolgirl, the schoolmarm. What she was herself was lost among the poses, and must have been lost years ago. It did not matter to him that there was something piteous in all this, but he was shaken by the sincerity that shone through it all. He had not stopped to think before that she must love Clay.

“He will attack Clay through you,” she went on. “He will do it so that Clay will either have to defend you or – Oh, I don’t know what!”

He did not speak and after a moment she said, as though she were pleading with him, “I think we are on the same side, Mr. Morgan. I can see it in your face.”

What she had seen in his face was the thought that he would rather have someone like Kate scratch his eyes out than Miss Jessie Marlow kiss them. But he could not scorn her concern for Clay. He sighed, removed his foot from the bale, and stood upright to light a cigar. He frowned at the match flame close to his eyes. She must think she was handling him as she would a bad actor among her boarders. “Well,” he said finally. “I guess I have a lien to pay off on that buggy ride, don’t I? What do you want? Me to pack on out?”

She hesitated a moment. She licked her lips again with a darting movement of her tongue. “Yes,” she said, but he had seen from her hesitation that there was more to it and it angered him that she might be one step ahead of him. But he nodded.

“So, since I am going anyway…” he said. He drew on the cigar and blew out a gush of smoke. She was working up one of her inadequate little smiles.

He finished it. “He might as well post me out.”

“Yes,” she said, in a low voice. She took a handkerchief from her sleeve and touched it to her temples. Then she wound it around her hand.

“I’d already thought of that. There is only one thing wrong with it.”

“What, Mr. Morgan?”

“Why, I don’t expect he’d want to. I don’t know if you’d understand why he wouldn’t want to, but I am afraid it would take some doing. What am I supposed to do?”

“Oh, I don’t know! I—”

“It would have to be something pretty bad,” he broke in. He eyed her with an up-and-down movement of his head. She flushed scarlet, but she was watching him closely nevertheless. There was no sound but the buzzing of the flies, and a creaking of buggy wheels in Grant Street.

Finally she said, “Will you try to do something, Mr. Morgan? For my sake?”

“No,” he said.

She looked shocked. She flushed again. “I mean for his sake.”

“If I can think of something.” All of a sudden rain splattered on the tile roof, with a dry, harsh sound like a fire crackling. He glanced up at the roof; a fine mist filtered through the cracks, cool upon his face. Miss Jessie Marlow was still staring at him as though she hadn’t noticed the rain.

“Just one thing,” he said. “Saying I can think of something and they post me, and I run from him like the yellow dog I am. Afterwards can you let him be?” His voice sounded hoarse. “Can you let him bank faro in a saloon or whatever it is he wants to do? Can youlet him be? There’ll be others that won’t, but if you—”

“Why, of course,” she said impatiently. “Do you think I would try to force—” She stopped, as though she had decided he had insulted her.

“Did you hear Curley Burne turning in his grave just now?” he said, and she flinched back from him once again as though he had slapped her. He saw the tears return to her eyes. But he said roughly, “You have been telling me a lot of things I ought to see – but you had better see this will be a place he can stop. If he wants to stop I will put it on you to let him. Understand me now!”

Her expression showed that she was not going to quarrel with him, and, more than that, that she thought she had cleverly brought him to the idea of getting himself posted. He had been considering it all day, but it cost nothing to let her think there was no man she couldn’t get around.

The rain rattled more sharply on the tiles, and she seemed to become aware of it for the first time. “Why, it’s raining!” she cried. She clapped her hands together. Then she got to her feet and put out a hand to him. He took it and she gripped his hand tightly for a moment. “I can promise you that, Mr. Morgan!” she said gaily. “I knew we were on the same side. Thank you, Mr. Morgan. I know you will do your part beautifully!”