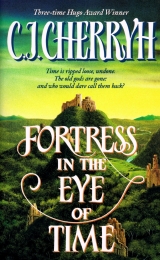

Текст книги "Fortress in the Eye of Time"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 47 страниц)

Fortress In The Eye Of Time

Fortress, Book 1

C. J. Cherryh

1995

For Lynn and Jane for a lot of hours ... through the lightning strikes and the rest of it

Chapter I

Its name had been Galasien once, a city of broad streets and thriving markets, of docks crowded with bright-sailed river craft. The shrines of its gods and heroes, their altars asmoke with incense offerings, had watched over commerce and statecraft, lords and ladies, workmen and peasant farmers alike, in long and pleasant prosperity.

Its name under the Sihhé lords had been Ynefel. For nine centuries four towers reigned here under that name as the forest crept closer. The one-time citadel of the Galasieni in those years stood no longer as the heart of a city, but as a ruin-girt keep, stronghold of the foreign Sihhé kings, under whom the river Lenfialim’s shores had known a rule of unprecedented and far-reaching power, a darker reign from its beginning, and darker still in its calamity.

Now forest thrust up the stones of old streets. Whin and blackberry choked the standing walls of the old Galasieni ruins, blackberry that fed the birds that haunted the high towers. Old forest, dark forest, of oaks long grown and sapped by mistletoe and vines, ringed the last standing towers of Ynefel on every side but riverward.

Through that forest now came only the memory of a road, which crossed a broken-down, often-patched ghost of a bridge. The Lenfialim, which ran murkily about the mossy, eroded stonework of the one-time wharves, carried only flotsam from its occasional floods. Kingdoms of a third and younger age thrived on the northern and southern reaches of the Lenfialim, but rarely did the men of those young lands find cause to venture into this haunted place. South of those lands lay the sea, while northward at the source of the Lenfialim, lay the oldest lands of all, lands of legendary origin for the vanished Galasieni as well as for the Sihhé, the Shadow Hills, the brooding peaks of the Hafsandyr, the lands of the legendary Arachim and the wide wastes where ice never gave up its hold.

Such places still existed, perhaps. But no black-sailed ships from the north came in this third age, and the docks of Ynefel had long since gone to tumbled stone, stones slick with moss, buried in mud, overgrown with trees, indistinguishable at last from the forest.

Call it Galasien, or Ynefel, it had become a shadow-place from a shadow-age, its crumbling, weathered towers poised on the rock that had once been the base of a great citadel. The seat of power for two ages of wizardry had become, in the present reign of men, a place of curious, disturbing fancies. Ynefel, tree-drowned in its sea of forest, was the last or the first outpost of the Old Lands ... first, as one stood with his face to the West, where the sea lords of old had fallen and new kings ruled, so soon forgetful that they had been servants of the Sihhé; or the last edge of an older world, as one might look out north and east toward Elwynor and Amefel, which lay across the Lenfialim’s windings and beyond Marna Wood.

In those two districts alone of the East the crumbling hills retained their old Galasieni names. In those lands of upstart men, there remained, however few and remote in the hills, country shrines to the Nineteen gods Galasien had known—while in Elwynor the rulers still called themselves Regents, remembering the Sihhé kings.

Nowadays in Ynefel birds stole blackberries, and built their nests haphazardly in the eaves and in the loft. A colony of swifts lodged in one great chimney and another in the vaulted hall of Sihhé kings. Rain and years eroded the strange faces that looked out of the remaining walls. Gargoyle faces, faces of heroes, faces of the common and the mighty of lost Galasien—they adorned its crazily joined towers, its ramshackle gates, fragments of statues seeming by curious whimsy to gaze out of the walls of the present fortress: some that smiled, some that seemed to smirk in malice, and some, the faces of Galasien’s vanished kings, serene and blind. This was the view as one looked up from the walls of Ynefel.

This was the view over which an old man gazed: this was the state of affairs in which he lived, bearded and bent, and solitary.

And, judging the portent of the season and the clouds, leaden-gray at twilight, the old man frowned and took his way in some haste down the rickety steps, well aware of danger in the later hours, in the creeping of Shadows across the many gables and roofs. He did not further tempt them.

Age was on him. His power, which had held the years and the Shadows at bay, was fading, and would fade more swiftly still when this night’s work was done: such strength as he had, he held close within himself, and guarded, and hoarded with a miser’s single purpose.

Until now.

He reached the door and shut it with a Word, a tap of his staff, a touch of his gnarled hand. Thus secure, he caught a calmer breath, and descended the steeply winding stairs with a limp and a tapping that echoed through the creaking maze of stairs and balconies, down and down into the wooden hollowness of Ynefel.

He lived alone here. He had lived alone for—he ceased to count the years, except tonight, when death seemed so close, so ... seductive in the face of his preparations.

Better, he had long thought, to fade quietly.

Better, he had determined unto himself, to deal no more with the Shadows and to stay to the sunlight. Better to listen no more to the sifting of time through the wood and stone of this old ruin. He owed nothing to the future. He owed far less to the past.

We deserved our fate, he thought bitterly. We were too self-confident.

And not virtuous, no, none of us virtuous. So it was fit that, in the end of everything, we killed each other.

Fit, as well, that we were neither thorough nor resolute, even in that extreme moment. To every truth we found exception; to every answer, another question. We doubted everything. We abhorred the demon in ourselves and doubted our own abhorrence.

And, inappropriate to the end, we linger. We cannot believe even in our own calamity.

Tapping of a knobbed and crooked staff, creaking of age-hollowed wooden steps—brought echoes, down and down to the foot of those steps, to the cluttered study in the heart of the fortress. There was sound in Ynefel, until he stopped, in the heart of his preparations.

There was living breath in this room, until he held his.

Always the gnawing doubt. Never peace. Never certainty.

There was even yet a chance for him to fare northward on the Road, to evade Elwynor and seek the Old Kingdoms that might, remotely might, remain alive in Hafsandyr. To walk so long and so far his aging strength might still suffice, or if it failed, in what innocence remained to an old wizard, he might lie down by that Road in the rains and the wind and sleep until life faded.

It would be a way to his own peace, perhaps, the ending his kind had never found the courage to make.

But he was Galasieni. He had not the resolve to believe even in his own death—and this was both the bane and the source of his power. He was of the Old Magic, and had no use for nowadays’ healers and wise women and petty warlocks with their small, illusory magics, least of all for the diviners and the searchers into old lore who wanted to lay hold of magics they could not imagine. Oh, illusions he could make. Illusions and glamors he could cast. But no illusions, now, would he work, as he squatted by the fire. He needed no books, no grammaries, nothing but the essence of his power.

He needed no fire. The air would have done as well.

But his hands reached into the substance of the heat, tugged at the very fabric of the flame and drew out strands that spun and rose in the remaining light. The strands drew upon the air, and drew on the stone of the walls and the age of the trees that made the dusty timbers of Ynefel: they built themselves, and wove themselves, and became.., a possibility.

Only one man had reached this skill, only one, in the age of the Old Kingdoms.

A second had reached for it, at the dawn of the Sihhé.

A third attempted it, this night. His name was Mauryl Gestaurien.

And the magic he wrought was not a way to peace. That, too, was characteristic of his kind.

He spoke a Word. He stared into a point in the charged insubstance of the air, tinier than a mote of dust. He was at that moment aware of the whole mass of stone around the room, aware of the Shadows among the gables, that insinuated threads into cracks and crevices of shutters, that crept among the rafters, seeking toward his study. He drew the light in Ynefel inward, until it was only in this room.

In that moment, Shadows edged under the doors and ran along the masonry joints of the walls. Shadows found their way down the chimney hole, and the fire shrank.

In that moment a wind began to blow, and Shadows jumped and capered about the rafters above the study, and seeped down the chimney like soot.

Came a mote of dust, catching the light, just that small, just that substantial, and no more.

Came a sparkle in that mote, that became a light like the uncertain moon, like the reflection of a star.

Came a creaking of all the ill-set timbers of the keep at once, and a fast fluttering of shadows that made the faces set into the walls seem to shift expression and open their mouths in dread.

Came a sifting of dust of the walls and dust from the wooden ceiling and the stone vault; and the dust fell on that point of light, and sparkled.

A gust of wind blasted down the chimney throat, blew fire and cinders into the room. Shadows clawed at the stones and reached for the spark in the whirl of dust.

But the spark became a sudden crack of lightning, whitening the gray stone of the walls, drinking the feeble glow of the fire into shocked remembrance of bright threads weaving, turning and knotting and coming apart again.

Mauryl groaned as the scattered elements resisted. He doubted. At the last moment—he attempted exception, equivocation, revision of what he reached for. On the brink of failure—snatched, desperately, instead, after simple life.

A shadow grew in the heart of the twisting threads, the shadow of a man, as the light faded.., shadow that grew substantial and became living flesh and bone, the form of a young man naked and beautiful in the ordinary grayness of an untidy room.

The young man’s nostrils drew in a breath. His eyes opened. They were gray as the stone, serene as the silence.

Mauryl shook with his effort, with the triumph of his magic ...

Trembled, in doubt of all his work, all his skill, all his wisdom.., now that done was done and it stood before him.

The light was gone, except the fire tamely burning in the hearth, amid a blasted scatter of chimney ash across the stones. Mauryl stretched out his hand, leaning on his staff with the other, the room gone close and breathless to him, light leaping in ordinary shadow about the clutter of parchments and birds’ wings, alembics and herb-bundles.

Mauryl beckoned, crooked a finger, the one hand trembling violently, the other clenched on his staff. He beckoned a second time, impatiently, angrily, fearing catastrophe, commanding obedience.

Slowly the youth moved, a tentative step, a second, a third.

Alarmed, Mauryl raised the knobbed staff like a barrier, and the advance ceased. He stared into gray, quiet eyes and judged carefully, conservatively, before he lowered that ward and leaned on his staff with both arthritic hands, out of strength, out of resources.

The Shadows lurked still in the corners of the study, moving quietly in the gusting of wind down the chimney. Thunder muttered from an outraged and ominous heaven.

The young man stood still and, absent the focus offered him by the lifted staff, gazed about his surroundings: the hall, the cobwebby labyrinth of beams and wooden stairs and balconies above balconies above balconies ... the cabinets and tables and disarray of parchments and oddments of dead animals and leaves. Nothing in particular seemed to stay his eye or beg his attention: all things perhaps were inconsequential to him, or all things were equally important and amazing; his expression gave no hint which. He put a hand to his own heart and looked down at his naked body, which still seemed to glow with light like candleflame through wax. He flexed the fingers of that hand and watched, seemingly entranced, the movement of the tendons under his flesh, as if that was the greatest, the most inexplicable magic of all.

Dazed, Mauryl said to himself, and took courage then, though shakily, to proceed on his judgment. He came close enough to touch, to meet the gray, wonder-filled stare of a fearsome innocence. “Come,” he said to the Shaping, offering his hand. “Come,” he ordered the second time, and prepared to say again, sternly, in the case, as with some things dreadful and unruly, three callings might prove the charm.

But the youth moved another step, and, feeling increasingly the weakness in his own knees, Mauryl led the Shaping over to sit on the bench by the fireside, sweeping aside with his staff a stack of dusty parchments, some of which slid into the fire.

The Shaping reached after the calamity of parchments. Mauryl caught the reaching arm short of the fire. Parchment burned, with smoke and a stench and a scattering of pieces on an upward waft of wind, and the Shaping watched that rise of sparks, rapt in that brightness, but in no wise resisting or showing other, deeper thought.

Mauryl braced his staff between himself and an irregularity of the hearthstones, whisked off his own cloak and settled it about the boy, who at that instant had leaned forward on the bench, the firelight a-dance on his eyes, his hand ...

“No!” Mauryl cried, and struck at his outreaching fingers. The youth looked at him in astonished hurt as the cloak slipped unnoticed to the floor.

A dread settled on Mauryl, then.., in denial of which he set the cloak again about the youth’s shoulders, tucked its folds into unresisting, uncooperative fingers. To his vexation, he had even to close the young man’s hand to hold it.

“Boy.” Mauryl sat down at arm’s length from him on the bench and, seizing the folds of the cloak in either hand, compelled the youth to face about and look him full in the eyes. “Boy, do you understand me? Do you?”

The youth blinked. The dip of his head that followed might have been a nod of acceptance.

Or an avoidance—as the gaze skittered aside to the fire.

Mauryl put out a hand, turned the face toward him perforce. “Boy, do you recall, do you remember.., anything?”

Another redirection, a blink, an eclipse of gray eyes, blank and bare as a misty morning. It might have been confirmation. It might equally well have been feckless bewilderment.

“A place?” Mauryl asked. “A name?”

“Light.” The youth’s voice began as a breath and grew stronger. “A voice.”

“No more?”

The youth shook his head, eyes solemnly fixed on his the while.

Mauryl’s shoulders sagged. His very bones ached with loss.

The eyes still waited for him, still held not the slightest comprehension, and Mauryl drew a breath, thought of one thing to say, that was bitter, and changed it to another, that accepted all he had.

“Tristen. Tristen is your name, boy. That name I give you. That name I call you. To that name you must answer. By that name I compel you to answer. My name is Mauryl. By that name you will call me. And I do need you, I do most desperately need you, —Tristen.”

The gray eyes held ... perhaps a spark of life, of further, dawning question. Mauryl let go the cloak, stared at the boy as the boy stared at him, open to the depths, utterly naked, with or without the cloak.

“Have you,” Mauryl asked, “no thought of your own? Have you no question? Do you feel, Tristen? Do you feel at all? Do you want? Do you desire? Do you think of anything?”

For a moment the lips looked as if they might frame a thought. The brow acquired the least small frown, but nothing.., nothing followed.

In the collapse of hope, Mauryl snatched his hand away, slid aside from the boy, fumbled after the staff that, rebel object, slid away from his hand away the wall.

Arm reached. Young fist closed on the ancient wood, flesh and bone certain as youth, quick as thought. Mauryl caught a breath, put out an insistent and demanding hand and clenched it on the staff, fearful of the omen.

He tugged gently, all the same, and the youth yielded the staff back to his grip, seeming as confused as before.

“You reflect,” Mauryl said, holding his staff protected in his arms, regarding the Shaping with despair, “you only reflect, like still water. I was much too cautious. I restrained what I called, and it crippled you, poor boy. You’ve nothing, nothing of what I want.”

There was no response at all but acute distress, mirrored maddeningly back at him. Mauryl turned his face from the sight, and for a moment there was silence in the hall.

A whisper of the cloak lining warned him, and the movement of a bare arm toward the fire ... Tristen reached, and in a fit of anger Mauryl grasped the hand, hard.

“No. No, you witling! Do you at all understand pain? Fire burns.

Water drowns. Wind chills you.” He shoved the young man, he flung him from the bench, scattered embers as the boy fell, his hand against the fire-bricks.

The boy cried out, recoiled, made a crouched knot of pain, rocking like a child, while smoke went up about the cloak edge that lay smoldering within the fire.

“Fool!” Mauryl shouted in rage, and snatched the boy away from the leap of fire, stepped on the hem of his own robe and, betrayed in balance, clenched his arms about the youth to save himself as he fell to his knees.

Young arms clenched about his frail bones, young strength hugged tight, young body trembled as his trembled, in a stench of smoking cloth, a burning pain where a cinder burned his shin. His own arms locked. He had no power to let go. The boy had no will to. That was the way they were, creator and creature, for the space of breath and breath and breath.

Maybe it was pain that brought water seeping from beneath his tight-shut lids. Maybe it was some motion of the heart so long ago lost he had forgotten what it was, after so long without a living, breathing presence but himself.

Maybe it was even remorse. That ... was much longer lost.

Undo what I have done? Unmake this Shaping?

I might have strength enough. But it would finish me.

The boy grew quiet in his arms. The stray ember had branded his shin and quenched itself in singed cloth. The pain of the burning and the pain of everything lost became one thing, as if it had always been, as if there had been, in all his planning and preparation, no choice at all. It was foolish for an old man to sit on the floor in the ash and cinders, it was foolish for him to cling to a hope—most foolish of all, perhaps, for him to plan beyond so signal and absolute a failure.

With gnarled fingers, he lifted the boy’s face. The tears had ceased, leaving reddened eyes, reddened nose. The face was no longer quite smooth.

Something had been written there. The eyes were no longer blank.

Awareness flickered, lively though pained, within that gray and open gaze.

There was before and after, now. There was then and now.

There was time to come. There was question and there was need, aching need, for some order in remembrance.

“I know,” Mauryl said, “I know, a rude welcome—and you have everything to learn, everything to find.” He lifted the boy’s hand, passed his thumb over the reddened palm, working a small, soothing illusion.

“The hurt is gone now, is it not?”

Tristen blinked. Tears spilled, mere aftermath. Tristen looked down, rubbing pale, smooth fingertips against each other.

“It will mend,” Mauryl said, and felt with only mild foreboding—perhaps a fey, wicked magic lingered—a net settling over the net-caster as well. All his anger was pointless against the youth, all his long solitude was helpless against the spell of warm arms, the quickening.., not of understanding, but of youthful expectations; the centering of them—on an old man long past answering his own. But he told the lie. He said in an unused, gruff voice, a second time, because the sound of it was strange to him, “It will mend, boy.” He reached for his fallen staff, he struggled with it to bring his aching knees to bear, and stumbled his way to his feet.

Tristen also stood up—and let slide the singed cloak, as if such things in no wise mattered.

Mauryl smothered anger, caught the robe with his staff, patiently adjusted it again about the boy’s bare shoulders. Tristen held it and moved away, his attention drawn by something else, the gods knew what—perhaps the clutter of vessels and hanging bunches of herbs in the room beyond.

“Stop!” Mauryl snapped, and Tristen halted and looked back, all unwitting.

Mauryl reached his side and with his staff tapped the single step to draw his attention downward, to the hazard he had never looked down to see.

“Tristen,” he said, “now and forever remember: you are flesh as well as wishes, body as well as spirit, and whenever you let one fly without the other, then look to suffer for it. Do you understand me, Tristen?”

“Yes,” Tristen said faintly. Tears welled up again, as if the rebuke and the burning were of equal pain. “Tristen, thou—”

He discovered something long lost, long ago relinquished, and it swelled larger and larger in his heart until his heart seemed about to burst with pain. He tried to laugh, instead, who had neither wept nor laughed since ... since some forgotten change, some gradual slipping away of the inclination. He made a sound, he hardly knew of what sort, knew not what to do next, and cleared his throat, instead—which left a silence, and the young man still staring at him. In the absence of all understanding, he put out a hand and wiped an unresisting face.

“An unwritten tablet, are you not? And a perilous, perilous one to write.

But write I shall. And learn you will. Do you say so, Tristen?”

“Yes,” the boy said, tears gone, or forgotten, cloud passed. There was tremulous expectation, as if learning should happen now, at once, in a breath.

And perhaps it should. Perhaps he dared not wait so long as a night.

“Come sit at the table,” he said. “No, no, gods, thou silly, hold the cloak, mind your feet ...” Calamity was a constant step away: unsteadiness threatened at every odd set of time-worn stones, so age must take the hand of youth, infirmity must guide strength that went wit-wandering in the search for a fallen cloak—and dropped the cloak again in utter startlement as a chair leg scraped across the stones.

Age found itself hungry, then, and warmed yesterday’s supper in the pot. Shadows lurked and flickered about the edges of the room. The thunder of a passing rain wandered away above the roof. But such things the Shaping more easily ignored, perhaps as a natural part of the world.

Waiting, between his stirrings of the iron pot, he came back to the table, where the youth hung on every word he offered, eyes fixed with rapt attention on him when he spoke—though gods knew how many bits and pieces of that flotsam a foolish boy could store away, or how he understood them at all.

He poured ale, that being the best he had. The youth first tasted it with a grimace and a puzzlement. He served yesterday’s beans—and the youth ate with a child’s grasp of the spoon, then, with the bowl unfinished, upon one cup to drink, fell quite sound asleep, head propped against his hand.

Mauryl took the spoon away, took the bowl, moved the arm, left him sleeping with his forehead pillowed on his arm on the tabletop, wrapped in an ill-pinned cloak.

It was a minuscule beginning of wizardry. Mauryl stood, hugging his staff, asking himself in a small fluttering of despair what he had done and what he was to do to mend it.

Wrap a blanket about the boy, he supposed, condemned, now, to simple, workaday practicalities. Ale had done its work. Magic had done what it could, and flesh and bone slumbered at peace, stirring forgotten sentiment in a wizard who had nothing to gain by it ... nothing at all to gain, and all the world to lose.

Chapter 2

Spatters of rain on the dust.

Trees whispering and nodding and giving up leaves, twigs sent flying.

Smell of stone, smell of bruised leaves, smell of lightnings and rain-washed air.

Taste of water. Chill of wind. Flash of lightning that hurt the eyes.

Boom of thunder that shook heart and bone.

It was like too much ale. Like too much to eat. Like too much heat and too much cold. Everything was patterns, shapes, sounds, light, dark, soft, sharp, rough, smooth, stone-cold, life-warm, and all too much to own and hold at once. Sometimes he could hardly move, the flood of the bright world was so much and so quick.

Tristen stood on the stone parapet, watched the lightning flashes fade the woods and sky and watched the trees below the wall bow their heads against the stone. Thunder rumbled. Rain swept in gray curtains against the tower, spattered the surface of the puddles and cascaded in streams off the slate of the many roofs. Tristen laughed and breathed the rain-drenched wind, raised hands and face to catch the pelting drops.

They stung his palms and eyelids, so he dared not look at them. Rain coursed, cold and strange sensation, over his naked body, finding hollows and new courses, all to the shape of him.

It was delight. He looked at his bare feet, wiggled his toes in puddles that built in the low places of the stonework and made channels between the stones in the high places. Water made all the dusty gray stonework new and shiny. Rain made slanting veils across the straight fall off the eaves and played music beneath the thunder-rumble. Tristen spun on the slick stones and slipped, recovering himself against the low wall of the parapet and laughing in surprise as he saw, below him, where the gutters made a veritable flood, brown water, where the rain was gray. A green leaf was stuck to the gray stone. He wondered why it stayed there. ...Tristen ....

He straightened back from his headlong dangle, arm lingering to brace himself on the stone edge as he looked toward Mauryl’s angry voice. He blinked water from his eyes, saw Mauryl’s brown-robed figure. Mauryl’s clothes were soaked through, Mauryl’s gray hair and beard were streaming water, and Mauryl’s eyes beneath his dripping brows were blue and pale and furious as Mauryl came to seize him by the arm.

He had clearly done something wrong. He tried to cipher what that wrong thing was as Mauryl took him from the wall. Mauryl was hurting his arm, and he resisted the pull, only enough to keep Mauryl’s fingers from bruising.

“Come along,” Mauryl said, and held the harder, so he thought saving his arm was wrong, too. He let Mauryl hurt him as he hurried him back along the parapet, Mauryl’s black boots and his bare feet splashing through the puddles. Mauryl’s robes dripped water. Mauryl’s hair made curling ropes and water dripped off the ends. Mauryl’s shoulders were thin and the cloth stuck to him and flapped about his legs and leather boots. The staff struck crack, crack-crack against the pavings, but Mauryl hardly limped, he was in such an angry hurry.

Mauryl took him to the rain-washed door, shoved up the outside latch with the knob of his staff, and drew him roughly inside into the little, stone-floored room. Light came only through the yellowed horn panes, storm-dimmed and strange, and the rain was far quieter here.

Mauryl let go his arm, then, still angry with him. “Where are your clothes?”

Was that the mistake? Tristen wondered, and said, “Downstairs. In my room.”

“Downstairs. Downstairs! What good do they do you downstairs?”

He was completely bewildered. It seemed to him that Mauryl had said not to spoil them. Mauryl’s were dripping wet. So were Mauryl’s boots, and his were downstairs, dry. It had seemed very good sense to him, and still did, except Mauryl lifted his hand in anger and he flinched.

Mauryl reached for his shoulder, instead, and shook him, deciding, he hoped, not to hit him. Mauryl would indeed strike him, sometimes when Mauryl was angry, at other times Mauryl said he had to remember. It was hard to tell, sometimes, which was which, except Mauryl would seem satisfied after the latter and far angrier than he had started after the former, so he wished Mauryl had simply hit him and told him to remember.

Instead, Mauryl beckoned him to the wooden stairs, and led him down and down the rickety steps. The soaked hem of Mauryl’s robe made a trail of rain drops on the wood, in the wan, sad light from the horn panes set along the way.

Clump, tap, clump, tap, clump-tap, downward and down. Tristen’s bare feet made far less sound on the smooth, dusty boards. He supposed rain didn’t spoil the clothes after all, and that he had guessed wrong. The water on the dust beneath his feet felt smooth and strange. He wasn’t sorry to feel it. But he supposed he was wrong.

And confirming it, when Mauryl reached the walkway that led to his room, Mauryl banged his staff angrily on the floor. His robe shook off more drops and made a puddle on the boards.

“Go clothe yourself. Come down to the hall when you’ve done. I want to talk to you.”

Tristen bowed his head and went to his own room, where he had left his clothes on his bed. The puddles he left on the board floor showed faintly in the light from the unshuttered horn panes. His hair streamed water down his back and down his shoulders and dripped in his eyes. He wiped it back and tried to squeeze the water out. It made dark tangles on his shoulders, and his clothes stuck to his body and resisted his pulling them on. So did the boots. His hair soaked the shoulders of his shirt, and he combed the tangles out, to look as presentable as he could.

Maybe Mauryl would forget. Maybe Mauryl would forget he had asked him to come downstairs and tell him to go away. Sometimes Mauryl would, when he was lost in his books.

The thunder was still booming and talking above their heads, and the water was still running down the horn panes—the horn was yellowed and sometimes brown: it had curious circles and layers and fitted together with metal pieces. The horn colored the light it let in, and the shadow of raindrops crawled down its face, which he loved to see. A puddle had formed on the sill, where a joint in the horn let raindrops inside. Sometimes he made patterns with the water on the stone.