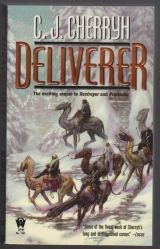

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

There was a heavy, heavy silence. “Is that his message?”

“No! No, nandi, that is not his message, that is his plan. He knew you were likely following. He wants you dead. He wants the heir in his hands. He wants Malguri. And we will not back him in this: there is no aiji over the East, and if there is ever one it will not be Lord Caiti! He has lied to us, he has misled, he has drawn us into a plot without consultation, and brought in the south without any authority—we do not consent to this, we do not bow the neck to this damned bully!”

“A pretty, pretty speech, nandi. And where is Murini?”

“Coming here, if Caiti told the truth—coming to ascertain Caiti does have your great-grandson.”

Ilisidi rolled her eyes up to the ceiling and down again, a gesture of exasperation.

“The truth, nandi, the truth this time!”

“Caiti is a fool!” Agilisi cried.

“So he will invite Murini under his roof, and demonstrate he has my great-grandson. And Murini, in awe of this astonishing fact, will obligingly leave my great-grandson in his hands while he goes off to become a target for my grandson’s forces. What do you think we are, Agi-daja? Equal fools?”

“Nandi, so he told Lord Rodi and me! And Lord Rodi went with him to the Haidamar, but I slipped back and my guard got me away—to come here, to consult with Lady Drien, to find some middle ground—some means to unite the independent neighbors in protest of this lunacy– Clearly, neither I nor my people were respected, to be brought there ignorant of all plans, to be confronted with this—we are innocent. I and my people are innocent!”

“A fine story. And all this plan was to get through our door in Shejidan, to make face-to-face contact with a traitor on our staff, carry out this monstrous idiocy, and we, of course, were to come rushing obligingly into ambush in the Haidamar.”

Across the lake, Bren thought: the image leaped up of a force from Malguri coming in by water, instead of overland, all exposed, and vulnerable. The dowager would not have done it.

Murini would have known that. Murini had some sense of tactics.

But did Caiti, whose people had faced Malguri across the haunted lake and quarreled about its isle for generations– did he think the dowager would be where she was at present, not at Malguri plotting to sail across, but overland, and past the jut of the south end cliffs to make peace with a splinter of Malguri itself?

Without that peace, Malguri might have found difficulty to cross that land quietly. There might have been alarms.

Certainly it was noisy enough to have drawn Agilisi in, claiming she had come to appeal to Drien.

And Drien, fresh from her acquisition of the disputed land, had said not one word to back her. That had to worry the woman.

“How can I prove my favorable disposition?” Agilisi asked—in truth, in a desperate situation. “How can I make Malguri understand that my district has nothing to gain here?”

“How indeed?” Ilisidi said darkly. “Except you tell the truth, every particular of this truth. When? How? Why? And with what force does this southerner invade the East at Caiti’s invitation?”

“Caiti plans to double-cross him, one believes.” Agilisi’s lips formed the syllables carefully, distinctly. “Nandi, we are betrayed, we are all equally betrayed.”

“Oh, one doubts equally, Agi-daja. One very much doubts equality in this treason. So you dared not go home. Who are his people in your household? Name them.”

“My nephew,” Agilisi said faintly. “But one pleads for him. He is young. He is associated with a Saibai’tet girl, a young fool. The one—the one to fear is his mother, Saibai’tet and resident with my brother. That onec that one I freely give to you.”

“Your brother? Or the Saibai’tet woman?”

“The woman, nandi. My brother’s wife. My brother is in a sad state of health, incapable of knowing what she signs, what she appoints, what staff she brings in to attend him.”

“Is this an accident, this indisposition? And do we attribute it to the wife—or his sister?”

Agilisi’s mouth hung slightly agape. She was not, Bren thought, a very clever woman—or her fabrications were not.

“One would justly have been suspicious,” Ilisidi said. Bang! went the cane. Cenedi moved up beside her chair. “I think this lady should have been far more suspicious. One needs more fingers than the gods gave us to count the betrayals. She fears to go to her domain. Clearly, she is in want of protection– granted we find out the truth in the next quarter hour.”

“Nandi!” Agilisi cried, looking from left to right. “Dri-daja!”

“This boy whose welfare is at issue is my youngest cousin,” Drien said coldly, “and has been shamefully treated by associates with whom you have willingly sat at table and connived, nandi. And now you bring your difficulties under my roof? We are offended.”

“The lady’s guard is resting below,” Cenedi said quietly, “nandi.”

Stripped of protection, her guard incapacitated, and the dowager as coldly angry as one was ever likely to detect—the unfortunate lady darted glances from one face to another, quick, reckoning, fearful glances.

“The truth, woman!” Ilisidi snapped. “Your ailing brother, indeed! You are the lord of Catien! You have permitted or not permitted this infestation of Saibai’tet servants and this woman under your roof, am I mistaken? Talk!”

“We were threatened!” Agilisi protested. “Malguri has done nothing for our region since you left! Who was there, nandi? Who was there on whom we could rely to sustain our independence? The aiji in Shejidan was lost—there was only the Kadagidi and the Taisigin! There was only them! I never chose to accept a Saibai’tet wife under my roof—but I had no power to resist, I had no great store of weaponsc”

“And Caiti did?”

“Caiti had the backing of the Kadagidi!”

“Ah,” Ilisidi said, and indeed, in that, a certain number of things made sense. “The backing of the Kadagidi. And was this maneuver Caiti’s idea—or Murini’s?”

“Caiti—” The woman seemed short of breath, as if there was not enough air in the room to get out what she had to say. “One suspects Caiti intends to double-cross Murini. Clearly– clearly—Murini is fallen and falling fast. He will surely go down.

But with his help—” She ran utterly out of breath, and drew in another. “Caiti means to take the East out of the aishidi’tat, build an Association here, holding the child—the child hostage against his father. He intends you should come there. He knows you will never negotiate, nandi.”

The plane that took off simultaneously for the South, the lord with the convenient excuse, a diversion, Bren thought, ticking off one southern lord who needed dealing with.

But they had plenty on their hands where they were.

“We shall not negotiate,” Ilisidi said quietly. “Nand’ Bren.”

“Nandi? We shall go wherever we need go.”

“One has no doubt,” Ilisidi said.

“Can either of these ladies open those gates?” he ventured to ask.

Agilisi glanced at him, clearly taken aback. Drien looked disapprovingly down her nose at his impertinence. Ilisidi, however, had raised that dangerous brow.

“Answer the Lord of the Heavens,” Ilisidi said, leaning chin on fist. “You can find your way back into Caiti’s good graces, can you not, lady of Catien? One is certain you can at least get the gates open—if only for their desire to know what sudden turn of events brings you back.”

“One might venture it,” the lady said. Gone, all her prim assurance. It was a straw, and with whatever motivation, she grasped at it. “One might, with your favor, nand’ dowager.”

“We shall hold my favor in abeyance, woman. You have walked into it and you know your life is sinking low, low indeed, in my present plans. Redeem it. And rest assured this is your one chance.”

“Agilisi is my associate, cousin,” Drien said, “and courted by lords Caiti and Rodi, as was I, as all the lords of the lakeshore and eastward. Her house was, indeed, infiltrated.”

“Is yours?” Ilisidi asked bluntly.

“My people have been with me all my life, Cousin. As yours.”

That, Bren thought, might be a frank and honest answer. A small silence persisted in the room, and Agilisi’s life quite literally hung on that silence.

“Our man’chi,” Agilisi said. “Rescue my house, nandi. We need your help. We appeal for your help. We quit this madness when we knew its intentionsc”

“Do you know the premises of the Haidamar?”

“Somewhat.” A tremor possessed the lady, who was not, herself, young. It might be a chill. Her boots showed water-stain, the snow having melted. But again, one doubted that tremor was in any sense chilled feet. “I have been there. I was a guest there, before this venture. Nandi, I had no knowledgec I appeal for protection of my house, my associates, nandi. I am putting them all at risk in turning to you. These are innocent people, my staff, my guardc”

Ilisidi lifted her hand, stopping the torrent short. “Their safety now depends on our success and my great-grandson’s life. Provide my staff a diagram.”

Getting through that gate. Getting the gate open, Bren thought.

That was all they needed—the bus that had brought Agilisi to Cobesthen might be able to break through, but finesse– finesse was going to get the boy out alive.

Agilisi looked about to wilt altogether, trembling visibly as she lifted a hand in protest. “One hardly knows,” Agilisi began, and then Drien: “We know those premises,” Drien said, the infelicitous dual augmented with the mitigating article. “And they will admit me, cousin, with my neighbor. Let me intercede for my neighbor. She may stay here. We shall ride to the north shore.”

It was gallant of the lady. It was downright grand, considering the peril of her association and the dowager’s outraged anger. There was still the remote chance Lady Drien was in with the kidnappers from the beginning—she had certainly been named; there was the remote chance Lady Drien had sought the promise of title to Ardija from Caiti, which could mean she was trying to lead them all into Caiti’s trap– But if a dozen years of reading atevi faces and manners was any guide, she had every appearance of telling the truth, and every reason for peace. Ilisidi as a neighbor was assuredly more stable than Caiti’s hare-brained effort to rip the East out of the aishidi’tat.

If they survived it.

“I would go,” Agilisi protested in a faint voice.

“Yes,” Ilisidi said, “but you shall not. Rely on my cousin for your survival. Become indebted to her. And expect your brother to lose a wife!” To Drien she said: “Cousin. You will find we remember debts.”

So they sat, with the same fire crackling away and all the players the same but one, and the whole East changed. We’ve landed in a damned machimi, Bren thought, not letting a wisp of expression to his face. He could even put a name to it: Kosaigien Ashai, as ancient and tangled a nest of pieces as existed in the dramatic repertoire. He had studied it, and never made thorough sense of the moves and the motives.

But there it was, the grand gesture, the acceptance, the realignment which had challenged human students for decades—a revised set of man’chiinc the principal’s own, and everybody else’s.

And blood to follow. A lot of it.

Neither Agilisi nor Drien had Guild help, as such—and the thought came through clear as a lightning strike: Cenedi and his men, Eastern themselves, would be recognized in a heart-beat.

Banichi and Jago might not bec but Jago had been at the dinner party.

Banichi, however, had not been: Banichi had not yet returned from the Guild that night. He meant to mention that fact to the dowager, at the next opportune moment. And he wasn’t sending Banichi and Jago off into a desperate situation without him, no way in hell.

“Where,” Ilisidi inquired further, “Agi-daja, where is the bus that brought you?”

“At the base of the hill, nand’ dowager. The very last of the road.

There is no driver. Your man took us at gunpoint—”

“We shall need that bus. Nand’ Drien, you may go with us.”

“In that infernal machine! Overland is the sensible way, overland or at very least by boatc”

“Come, come, Dri-daja, straight into ambush? You need new experiences. You are not too old. We need you.”

“Then overland!”

“We cannot dither about riding there, not with my great-grandson—your cousin thrice removed!—at issue! The bus may need to go further, but it goes faster, and does not wear us down.”

“I am far too old for that rattletap!”

“If I fare well in a bus,” Ilisidi said, “you may survive it. And your staff, Dri-daja, can bring the mecheiti overland. You shall ride with us and arrive ahead of them, I wager you on it.”

“One has never agreed to this machine!” Drien cried.

“One has not written down the disposition of Ardija, either,”

Ilisidi said primly, and called for pen and paper.

Three quarters of an hour later Ilisidi had signed and sealed a note ceding Ardija, the lady Agilisi and her sole retainer were confined to a comfortable though chilly room in Cobesthen Fortress, and the rest of them were on mecheita-back, with the entire local herd and the Malguri herd together, all riding down toward the intersection and the waiting Cadienein-ori airport bus.

It was a whole damned cavalry, Bren thought, and the two herd bulls were not in the least compatible, Drien’s and Ilisidi’s. They raised a bawling complaint all the way down the road, prime reason to take the bus and not have that all the way around the lake shore, announcing their presence.

And having hastily having thrown on his warmer coat and trousers and having left all but his most essential baggage under Drien’s roof, Bren tried to keep that shorter coat spread out over Nokhada’s warm, winter-coated body, holding as much of her heat near his body as he could. The bus itself was not going to be comfortable, he was damned sure.

It sat, dark and dead, right amid the one-lane road, with snow piling on its hood and top—a stubby half-bus transport. A delivery van might have been more commodious. It said, on the side, in large letters: Cadienein-ori Regional Transport Authority.

It offered no sign of life as Cenedi’s men investigated it end to end and underneath. Two bundles went out, unceremoniously, likely Lady Agilisi’s luggage, right into a snowbank. One of Cenedi’s men started the engine, and reported a half a tank of fuel.

“Enough to get down to the depot,” Cenedi said, getting down.

Nawari slid down and held Babsidi’s rein, urging him to kneel.

Ilisidi got down, and Drien followed, helped by her own people, while the squalling between Babsidi and the other herd leader went on and men strained to keep snaking necks out of play.

Bren secured the rein, slid down to the snowy ground and got out of Nokhada’s way in a fast move to the side of the bus.

Cenedi himself elected to drive; and all of them, Banichi, Jago, Nawari, and all the rest of the dowager’s men took to the bus in haste, except the one of the dowager’s men assigned to handle Babsidi, and go with Drien’s men and the herds overland to rendezvous with them at the Haidamar.

There was no loitering, either, with mecheiti involved. “Go!”

Nawari told the men with the herds, and Drien’s men headed off into the dark, down the road ahead and off it, in short order.

Ilisidi had meanwhile appropriated the front seat, Drien was, one could see through the small back window of the cab, compelled to the second row, and Bren jammed himself up close in the fifth with Banichi and Jago: cold, poorly padded seat, cold metal floorboards underfoot, and a draft from the ill-framed windows, but that was minimal discomfort, all things weighed against a long cross-country ride. A lone, relatively thin human was very grateful to be surrounded by atevi that gave off heat like a furnace.

Weapons were everywhere. The bodies around him were armored, another good thing, in the paidhi’s estimation. The engine growled, and the bus got into motion, backwards. Bren stayed very still, with his hand on the gun in his coat pocket, as a last two shadows climbed up onto the bus bed, both the dowager’s men, dim silhouettes bristling with armaments, and made their way down the aisle to the rear of the bus.

The bus kept backing. Would back, until they reached a turnaround, and Bren could not readily remember how far back that wide spot was.

So they were off, and Agilisi waited the outcome. The lady had arrived expecting to politick with Drien and now had an unenviable refuge in Drien’s upstairs, doomed to wait, and hope it was not the other side that showed up. Her man, not Guild, and vastly outnumbered and outgunned, had no part in the dowager’s party, or in Drien’s, but one had to remember that unfortunate man had a partner somewhere, and that partnership would not be split, not by anything less than death or highest duty. Consequently, the household staff, such as remained, was under Drien’s orders to admit no one of that man’chi.

“Is there,” he asked Banichi and Jago finally, while the bus was still, in reverse, navigating the track downhill, “any remote chance she knew the dowager was here?”

“No one at Malguri would have given out that information.”

“Drien’s staff does have a telephone.”

“Tapped, Bren-ji,” Jago said with what seemed a certain personal satisfaction, “and no message went out or in.”

The virtues of having a lot of Guild security staff about one’s person. Efficiency. They lacked Tano and Algini, who ordinarily managed electronics and explosives, but things got done.

And that—besides Drien’s sudden self-interest in seeing the dowager win—gave one a certain notion the lady with them had told the truthc the ink might be hardly dry on that pact, but it gave Drien a powerful motive; and Agilisi could only hope they got back in one piece and that it was the dowager’s previously negotatied mercy she had to trust. Drien’s household was there to swear to what she had said and done.

But it was a good situation. Not an enviable place to be.

And damn, could the woman not have come with a full fuel tank?

The bus reached the wide spot, executed a precarious turnaround, then picked up speed.

They had to go clear back down to the airport road. But they did as they could. It was what they had. And they moved as fast as a vehicle of this vintage could managec en route back to the valley, to clearer, less winding roads, and, ultimately, a fuel station. The lake sat in an old crater—Malguri on the highest side, with its impregnable cliffs; Cobesthen to the south and the Haidamar to the north of it; and they were headed down, if not on the flat, at least on flatter ground, between Caiti’s two holdings of the Haidamar and the Saibai’tet Ami, and very much within his domain for most of their trek, verging on Catien for a small part of it.

And if Caiti made a run for it—could they possibly get intelligence of such a move, which might be designed to carry the heir to some other prison? Could they get between him and the Saibai’tet? That depended on where the roads lay, and he didn’t know that answer.

But Murini, Agilisi had said, was coming to the Haidamar, likely from the airport at Cie, judging that Malguri Airport would not be a good landing spot. Murini meant to take the heir in hand and would gladly take on the aiji-dowager and any force she could bring to bear, presumably while Caiti sat and watched, basking in this new and favorable alliance.

Ilisidi was moving as fast as she possibly could to get ahead of this train of events. She had not threatened war. She had not called in the Guild, unwelcome in the East. She went directly after her great-grandson, and went after him in the dead of night, in a snowstorm, and maybe that was the best choice, and maybe it was not.

Get through the gates, and hope to God they were the first to do so.

Once Murini got his hands on Cajeiri, there was no question of Murini leaving the boy in Caiti’s hands, no hope of that, as he figured it, not unless Caiti was a damned sight cleverer than any of them thought he was. And what Caiti had tried, never mind he had succeeded this far, did not encourage them to believe that he was all that clever.

Bren found dinner sitting very uncomfortably as the bus lurched and tilted on the narrow road, rocketing downhill, all but out of control on an unfamiliar road. Everyone swayed. A few had heads down, against hands braced on the seats. If he were at all sensible, Bren told himself, he would try his damnedest to sleep while they traveled. It was going to be a long night, a long way around. The Guild with them knew it. The Guild took its rest where it could.

But he doubted he was going to be able to.

He heard certain of Ilisidi’s young men debating the wisdom of trying to get through to Malguri, whether their satellite phones were help or liability in this situation—he heard frank discussion of other Guild being sent in, if Tabini-aiji got the straight word on what was happening, and about the likelihood of Eastern disaffection, and the plain fact they were just that far from help.

This, as the bus hit the lowland road. It assumed a roaring fast pace for about an hour, and then slowed and pulled in—the fuel depot, Bren thought, where the road passed through a finger of Lady Agilisi’s district of Catien—or he was thinking that, when Banichi and Jago flattened him to the seat.

The rest of the men scrambled out. Bren stayed down as Banichi and Jago followed. It was very quiet outside, and then came the distinctive sound of the fuel cap going off the bus and the hose going in.

There was such a thing as trust, that of his bodyguard toward him, a contract of obligations. He obediently stayed flat the while the refueling went on, not satisfying his curiosity, not even lifting his head from the seat. Banichi and Jago didn’t need his help on this mundane task, not in the least.

He heard voices, quiet ones, against the side of the bus. One mentioned something about the attendant being in the cellar.

That was informative.

The cap went back on. Everyone boarded again, Banichi and Jago among the first in, and wanted their seats, which he supposed gave him leave to sit up.

Jago set a hand on his shoulder as she eased in.

“Cenedi has called Malguri on the depot phone, Bren-ji. They are aware. They will get word to the aiji.”

“Good,” he said. Well that Tabini at least be warned what was happening. He had the most amazing disposition to shiver. “Are we all right?”

“A plane has landed in the north,” Banichi said. “At Cie.”

“From?” he asked.

“No one is sure of its origin,” Jago said. “It may be scheduled freight. It may not. It is worrisome. Planes are entering Eastern airspace again. Malguri Airport itself is back in operation. Guild may have come in. We did not inquire.”

They wouldn’t. They wouldn’t raise the question for fear of blowing cover. Malguri had seen fit to tell them that was going on, but there was no telling what else was.

Which meant they could be neck-deep in a shooting war by morning. It didn’t help the chills, as the bus started up and began to accelerate away from the fueling station.

“Did we kill anyone back there?” he asked. He didn’t know why he asked. He didn’t want to know, except that he wanted some sense of how far the dowager was holding off the people of Catien, whose lady was locked in Drien’s upstairs. He hoped there was still a modicum of civilization in this district, that there was still some sense of restraint governing the lords “No,” Jago said. “They were very wise, and respected the sight of the lady of Catien’s ring.”

So they had that—by force or by gift: Agilisi’s seal on their use of her goods.

“They are locked in the storeroom,” Banichi added, as the bus reached its traveling gear, “where there is no telephone, nor radio.

They believe someone will come along before noon tomorrow.”

13

Chip and chip and chip. The outer halls were quiet now. The light was off out there. The light had gone off in here, too. One had no flashlight: that had gone, with the other cell. One could no longer see what one was doing. And Cajeiri’s fingers hurt. Probably they were bleeding, but one could ignore that when one was mad. And Cajeiri was mad by now. He was damned mad, and tired, and grew madder the more it hurt.

He was, however, well through the plaster coating. He had come up against a bare spot of what felt like thin boards, which he could just get the thin, flat end of the bucket handle into. He pulled.

Repeatedly. He said bad words to himself, in ship-speak.

One thin board broke with a snap like thunder, and took plaster with it.

That was good. He got much of his hand in. He pulled another board. He began to grin, partly from the effort and partly from the success. He wriggled around and applied both hands, which broke more boards and brought more plaster onto the floor where the bed ordinarily rested. Beyond that was a gap. And rubble. He ripped out pieces, rocks, some fist sized. None of them were mortared in, or if they were, it was entirely haphazard.

He began to get the picture of a neat plaster facade and some sort of rubble fill between. Cheaply done, mani would say, and sniff at it. A quickly done wall in a building this old. Maybe dividing something off, on the cheap. That was interesting. It was not at all how they built on the ship. He could do something with this.

He started scraping the opposing wood with the use-sharpened flat end of the bucket handle, scrape, scrape, scrape. His knuckles bled. That was no consequence. Temper kept him warm on the cold floor. Temper kept him going when they might expect him to be asleep.

He wished he had Gene’s help. Artur’s. He imagined that they worked beside him, Fortunate Three, and that made matters better. He ought properly, he knew, to think of his Taibeni associates. He belonged to them. He feared they might even be dead because of those people who had carried him away from his bed, a thought which roused a keen and proper pain in his heart; but when he really, seriously wanted help, he naturally thought of Gene, who was always ready for a scheme, who thought of things, really clever things, instead of looking at him for help.

Gene and Artur had no idea where he was now. They could never imagine the trouble he was in at the moment. If they did know, they would be trying everything to get to him—if they were not separated by space and authority and adults. And that, when he got out of here and if he got to grow up, that was going to get fixed.

They were his first associates, the first beings in all the world—or above it—who had ever come to him, as persons of his own age and rank– Well, at least they were all of them passengers, and so they were equals in that way; and they were still his, in a special way.

Gene and Artur. Their coconspirators, Bjorn and Irene, he let into their company for felicity’s sake and to please mani-ma, so they were at least a Completion of Five, which was very solid and respectable, like a social group. But increasingly he kept forgetting Bjorn, and now in desperate case he began thinking just of Gene and Artur and Irene, his Felicity of Threec Because he was gone from them. He was gone from them and unless he could get back or get them down here, they would go their own way and be human, and he would be atevi– Damn it.

Granted he lived through this.

Scrape and scrape and scrape. The spoon kept bending, but the bucket handle held out. It was slick with sweat or blood, he had no idea which, in the dark. It made a gritty paste with the mortar scrapings and the dust, and one end had sharpened. It made it a better tool.

Damn them. Damn them, Bren-nandi would say. He was by no means sure what that meant, but Bren was careful about saying it, so he figured it was potent.

He did hope he still had Antaro and Jegari, if they were alive.

And he knew beyond any doubt in his very core they would want to find him—if they were still alive. He really, desperately hoped they were. And in between imagining Gene and Artur, he imagined Jegari and Antaro going to his father, and telling his father what had happened.

Oh, then all hell would have broken loose, and they would call his great-grandmother, was what, and they would tell nand’ Bren. The whole world would be looking for him by nowc Granted his father and mother were still alive. Granted the Bu-javid was not back in the hands of Murini and his associates, which was the thought that scared him most and made him stay awake and keep digging.

He scraped a knuckle, gritted his teeth, and scraped away, which necessarily hit the knuckle over and over and over.

He wanted them all to be alive, and looking for him. He wanted his father and mother to be alive. He wanted mani to come and get him. He had complained about their discipline, and never thought he would miss it, but now he wanted them, he wanted their rules and their law around him. He had never been alone in his life, not alone like this, and if he stopped fighting long enough, he could be scared, which mani’s great-grandson never could be. So he kept at it.

Scrape and scrape.

Damn!

Something resisted. He got fingers into it, and found something like– Wire. Two or three strands of it. He pulled, popping it past boards and plaster, and pulled, bracing his feet.

It might be part of the construction, some sort of reconstruction.

But the more he pulled it, he began to think it was really wire, metal-centered wire, electrical wire. Somebody had made a very inelegant repair when they plastered up the wall, was what.

He was by no means sure he could get the mess loose, but he wanted it. He wanted it out of his hole, for one thing; for another– For another, an idea was coming to him, even if the light switch was on the other side of the door.

There was a light socket in the ceiling.

He braced both feet and hauled, and hauled as the wire resisted.

One end came out, and he tested it gingerly with the bucket handle.

No spark. Dead. Entirely dead.

But it was metal-centered. It was old and dusty and twisted, but he had a lot of it and it was metal. And if he could cut it off or bend and break it and get it into his handsc He tried breaking it. Hauling on it. Got out from under the bed and hauled on it until it cut his fingers.