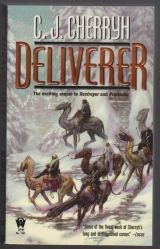

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

The numbers had shifted. The trend had changed. And Tabini had not been able to do it until the key items of his own numbers, protected from the coup by distance, had reassembled and started moving.

At that point, Murini had started to topple.

Interesting, looking at it from the inside.

“About a television in his great-grandmother’s apartment,” Tabini said, “—we remain doubtful. We resist his notions of bringing this Gene down to earth. We further hope our son will not demonstrate his command of Mosphei’ for the news services. But, over all, well done, paidhi-ji.”

“One is grateful, aiji-ma, knowing one’s great shortcomings.”

“Nandi,” Tabini said sharply, “you will sit in the legislature in all the honors of your lordship, should you choose.”

Tabini would back him that far, and ram his presence as a lord of the aishidi’tat down the throats of senators jealous of their ancient prerogatives. He quietly shook his head. “I shall not vote, aiji-ma, nor attempt to hold a seat there. I cannot advise impartially, if I vote, nor can a human decide matters for atevi.”

“Better than some who hold that post,” Tabini said, though clearly he was not put out by the refusal. “But your ministerial rank and your lordship stand. I am adamant on that matter.”

“Not to any detriment of yourself or the people, aiji-ma. One would not wish that.”

“What great reward would you desire for yourself, nand’ Bren?

What could we give you? A television?”

He laughed a little, and then thought of one thing. “Word of my brother, Toby, aiji-ma. He has not reached the island since he brought us to the mainland. That is my greatest personal concern.”

“My grandmother told me so. So, indeed, has my son. Both have requested a search. It is already in progress.”

“Then I shall be patient as well as grateful,” he said, indeed grateful that those two had set it so high in importance. And that Tabini had. He was better-cared-for than he had knownc than perhaps even his staff had known, though he was not sure on that point. “Thank you, aiji-ma.”

Tabini looked at him a long, long moment. “That you have no permanent residence in the Bu-javid is more than an injustice. It is our personal inconvenience.”

It was well-known there was no space for new families.

Residency in the Bu-javid was the most jealously guarded of privilegesc and he had had such a place, which now was bound up in politics—a difficult matter, with several deserving houses wanting the honor and the space and a touchy one already fighting for it. “Even if it were possible, I would not violate the precedences of those waiting for room.” He attempted a modest joke. “There would be Filings, and there are already so many, aiji-ma.”

Tabini laughed outright, but briefly, not to be diverted. “We will consider the matter—should Lord Tatiseigi return to court. As, who knows, he may, soon. You would not be averse to resuming the Maladesi residence once that matter with the current residents is sorted outc”

“I would not, aiji-ma, or any other the aiji might deem just, but—” What in hell were they going to do with the family who had occupied it? Was Tabini proposing to add that household to his list of enemies?

“But there is the present solution,” Tabini said, “until Tatiseigi returns. We take it you are comfortable in your current situation.”

“Very much so, aiji-ma.”

“Then we shall let it rest for now.” Tabini’s conversation thereafter bent to administrative committees and details, current matters under investigation, inquiries on communications with various committee heads.

That Cajeiri had not interrupted the audience was both unexpected and somewhat disappointing—he hoped the boy was not forbidden to see him. He supposed Tabini was bearing down on protocols, and needfully so, and no, his son should not come bursting into audience as he pleased. It was a new and rule-rimmed existence Cajeiri had entered.

So they drank their tea, and settled several committee matters.

Bren asked no questions about the boy, nor had any answers volunteered. Tabini, he concluded, had taken his son back, as he ought, and Cajeiri was, by implication, no longer the paidhi’s business.

He took his leave, finally, taking with him a small folio of important papers which were part of committee agendas with Transportation and Commerce. So his wild days were settled, now, and it was back to committee meetings, tedious oratory, and something of his old function. It seemed forever since a committee meeting had occasioned a rush of adrenaline. He wasn’t sure he could still muster it in such an instance. And, damn, he’d rather hoped to see the boy before he left.

Nand’ Bren had left, before ever Cajeiri had heard he was on the premises, and Cajeiri knew, after dealing with his father and his mother, that complaints about the matter after the fact would find no sympathetic ear at all.

No matter he was angry enough to fling his stylus at the wall—he restrained himself from doing that, and discovered that the very deliberate act of returning his stylus to its box and straightening his paper on his desk likewise rearranged his temper into more potent order—a temper stored up, filed, labeled, and ready to access when it counted.

With that small angry treasure on an otherwise bare mental shelf, he called a servant—not Pahien—to call his great-grandmother’s chief caretaker, the older man, Madiri, who had the premises under his care, and a small staff at his disposal.

He could have gone to his father’s major domo, or his father’s servants, or his father’s bodyguard: but these new people that had come in with his father, in the way of servants new to their posts, would run somewhere higher up for instruction, possibly all the way to his fatherc no, Madiri was definitely the way to go.

“One is greatly distressed, nadi,” he began his protest, “that my great-grandmother’s staff, knowing my association with nand’ Bren, did not inform me he was here.”

“One assumed,” the good old man began, but it was unnecessary to listen to his lengthy protest.

“We know,” he interrupted the man, “and entirely understand your position, nadi. But they are all new, and have no concern for our wishes. We were not even thought of, one is quite sure. Where is my staff at the moment?”

“Your senior staff, young sir, is attending your wardrobe, I believe, and changing the linens.” Senior staff was the pair of personal servants lent him by great-uncle Tatiseigi, more spies, he was quite sure, to go with the bodyguards he had from both Great-grandmother and Great-uncle. Not to mention the domestic staff, that opened drawers and went through his spare shirts—and everything else. “Your senior security, young sir, is absent at a general Bu-javid security briefing.” That was the pair of his great-grandmother’s own, Casimi and Seimaji, honest young men he honestly would rely on for safety—and rely on to tell his great-grandmother every time he sneezed, too. They made incomplete four, counting Uncle Tatiseigi’s two, which, with him, and counting also his two young attendants, made fortunate seven, his aishishi. But Casimi and Seimaji agreed with Great-uncle’s pair much too often. If he had to have anybody of Great-grandmother’s guards, he would wish tor Nawari, who had a lively sense of humor—but Cenedi took him, and put grim old Casimi in charge. It was maddening.

Then Madiri added, almost as an inconsequence: “The young staff is still absent, one believes, also on some sort of errand: they said it was on your behalf.”

Getting supplies from the town, that was the story. He had sent them there himself, and that had been unlucky coincidence, because if they had been here, he would have known Bren had come in, no question about that.

“My father’s staff, being new in their posts, has to ask permission before granting me anything, and that takes far too much time, nadi. You know very well what my great-grandmother allowed, that I should be allowed.”

“One must protest, young sir, that there is no authority in my hands to admit or fail to admitc”

“There was no question of admitting anyone yourself, one protests, Madiri-nadi, but simply to inform us of persons coming and going, persons I may know. My father and mother are too busy even to think to inform me, and it would look very odd, would it not, for them to be sending staff to me at every moment? They will not regularly consult me. One must rely on Great-grandmother’s staff, who one thinks should attend to me far better than these new people. We were greatly embarrassed to have failed to greet nand’ Bren. We were set at extreme fault.”

The man looked chagrined at the accusation and flattered by the grant of responsibility, however strangely that combined. And everything he said to the old man was fairly close to the truth, however slightly re-aimed and refined to have his way.

“So the young gentleman will wish to see nand’ Bren at next opportunity.”

“Indeed, nadi, we wish to see nand’ Bren, or our cousins, or Great-grandmother’s staff, or nand’ Bren’s staff, or any people we know, nadi-ji. We are shut in. We are a prisoner here. We are desperate, nadi, to see people we know. We are so lonely, nadi!

Papa-ji hardly means this to be the case. But he is busy. He is always busy. We have only you, nadi.”

Exactly the right nerve. The old man nodded sympathetically and bowed. “One hears, young sir.”

“One will remember such a kindness,” he said, meticulous in the manners Great-grandmother had enforced with thwacks against his ear. “Thank you, nadi.”

“Indeed, indeed.” The old man bowed again, and went away at his slight signal—as slight as his great-grandmother’s: in fact, precisely hers—he had practiced that little move of the fingers, with just the right look. It worked.

So he was still angry, and absolutely certain his father had perfectly well thought about him during Bren’s visit, and decided not to tell him, because he was not to be that important in the household, nor should think it for a moment—but he had at least done something about getting information.

He longed desperately now for Gene, for Artur and Bjorn and Irene. He missed racing cars with Banichi or studying kyo languages with Bren, who could always make him laugh. His heart would widen just at the sight of Sabin-aiji, or Jase, or Nawari—or Great-grandmother or even Great-uncle, for that matter. He longed for anyone more than the staff that soft-footed it around him, delivering food or drink or just maddenly hovering, ready to pounce and pick up things he might drop. He was not altogether overstating his case with the old caretaker. It was driving him to desperation. He hated the hovering of servants. He hated Pahien standing outside his room just so she could dive over and be the first there, any time he needed anything.

He hated most of all being shunted aside and told he was a child.

Most of all—loneliness, after being in the center of things, was entirely unjust, and such injustice—hurt. Hurt made him sulk.

And sulking only worried the servants and brought them to hover around him. Especially Pahien.

So he did as Great-grandmother had instructed him and sat straight and kept his face composed, struggle as he had to just now.

It was, she would say—he could hear her voice, and almost feel the ping of her finger-snap against his ear—an excellent lesson for him.

He should be grateful to be inconvenienced.

The hell, nand’ Bren would say. The hell. He could hear nand’ Bren say that, too, under his breath—esteemed nand’ Bren, whose face showed absolutely every thought, and who laughed so nicely and who was angry so seldom—he so wished Great-grandmother had sent him to live with nand’ Bren and his staff. There were people with a sense of humor.

But he was obliged to get acquainted with his parents, who elicited his stories at supper, and seemed to appreciate them—they mostly laughed in the right places—but some things clearly failed to amuse them at all, and occasionally when he thought something should be funny, or impressive, he saw definite signs of their disapproval—disapproval of him, of his experiences, and his enthusiasm for human things, over all. Mani-ma had warned him, and now he understood: he had to keep certain things to himself, and not talk about them.

He went back to his diary, which he kept in ship-speak, in the ship’s alphabet, and which he trusted no one could read except maybe his father and his father’s security—accordingly he kept it locked away in a secure place, along with his kyo studies, and his pictures, the ones he had drawn and the photos from the ship, which he had gotten from Bren’s report.

He would meet Prakuyo an Tep again, so he hoped. And once they had the link to the ship running, he wanted to download some tapes he knew the ship had, so that he could practice his kyo accent.

Once that link was running, he most of all wanted to talk to Gene—but he was sure his father would not approve that conversation, especially if it could become public.

Everything going to and from the ship ran through the Messengers’ Guild: that was the problem. The Messengers’ Guild had not been the most loyal of the Guilds during the trouble, and his father mistrusted them. So if he was going to talk to Gene, he had to think of ways to do it in some secrecy, or at least in some words nobody else could understand, and he was thinking on the problem.

This residency with his father was a test of character, mani-ma would say. Well, so it was. Perhaps it was also a test of his ingenuity and resolve. Was that not part of his character? If he and his personal staff—Antaro and Jegari—had succeeded yet in penetrating the communications system, he would have known Bren was coming.

But that failure of information had turned up a flaw in their assumptions: proper invitations did not come through the phone system, but in writing, by way of that small silver bowl in the foyer, to be hand-carried by staff, or, between closest allies, simply given verbally from staff to staff: that was a problem to penetrate.

That meant someone had to be stationed in some position to overhear what was going on—or there had to be a microphone, and there had to be loyal staff to monitor it, the way they had had in the security station on board ship—he did not think he and his young staff could manage anything that elaborate, not past real Guild.

But he had been used to that system on the ship. Security staff had always been sitting there in one little room full of equipment, doing things that had been a mystery to him during the first half of their voyage—but not after he had seen them in action in a crisis.

That station had been aware when any door had opened, and when anyone left and whether they had come back safely—and they had learned to get by it, getting out. There was, in fact, exactly such a station in mani-ma’s very apartment, right down the hall, where now his father’s people were in charge—it was very great trust for mani to let his father’s very new staff handle that equipment. And that might even argue that mani had gotten one of her own people into his father’s staff.

Probably she had. He bet she had. Such things certainly went on, as Uncle had wanted him to have Atageini among his guards, not trusting the Taibeni, oh, no, not with centuries of bloodshed between Atageini and Taibeni. And then mani had gotten her own two guards in because she wanted to watch the ones Uncle sent.

And that meant if he was going to get information and get him and his staff in and out past his father’s security, he had to figure on Great-grandmother’s staff and on Great-uncle’s, too– but they would be busy watching each other.

He was supposed to be learning. He certainly was.

Getting information out of his father’s security station, which was always manned, meant getting it out on two legs. And that meant getting Antaro or Jegari or someone into position to find out things. Antaro and Jegari’s age, and most of all their status as non-Guild, made that all but impossible. And if they were to take Guild training, which Banichi said they could do, that would take them away from him just when he needed them desperately.

Damn, Bren would say. That was no good.

Freedom such as he had enjoyed on the ship was going to take some work. Phone-tapping could be useful, but it never would give them things that flowed on the house system, he was sure of that.

But he had not set everything on that plan. He was working on other projects, and Jegari and Antaro had in fact slipped out on his orders—to all appearances, they had simply walked out, on the legitimate excuse of visiting relatives in the hotel down at the base of the hill. And because he was sure at least Great-uncle’s people were watching his staff for misdeeds (Atageini never trusted Taibeni) he had told the two of them to get their cousins to go out shopping down the hill. And they were to bring back ordinary things like clothes to wrap the electronic items and tools they needed and were going to buy at the same time. It was amazing how hard it was to get a simple screwdriver in this place.

He, meanwhile, was mapping out the pipes and conduits, and doing it mostly in his head, because Uncle’s staff was large-eyed, and, he suspected, reporting everything.

Perhaps Uncle’s staff reported he was a zealous student, spending a great deal of time in the library—where staff did let him go with only Jegari and Antaro in attendance, because the apartment and the library were in the same secure area.

Perhaps the librarians reported he had a fascination with engineering and history. Both were true, so far as the plumbing and electrification of the Bu-javid went. He had pulled down every book on the building’s history he could find, there being no manuals to show how things were now. There had used to be a gas system, but it was disconnected. There had used to be fireplaces, but they were in disuse, and many had been walled up, their flues—that was the word—still there, sometimes converted to bring in fresh air to the ventilation systems, but often just remaining hollow spaces behind masonry or panelsc which was why certain places were spying-spots, and you could hear things that came through the old conduits: a number of these had been filled in, and people who worried about security worried about those things.

The history of the Bu-javid was, in fact, a long, long chronicle of modifications and reapportionment of space. The kitchens had lost their hand-elevators when one had been used in the assassination of a lord of Segari, a hundred years ago. Now food came up by the main elevators. The stairs that servants used, some of which did interconnect, or had used to interconnect, had also used to have guards.

Now the various establishments in the building all had security systems like the ship. Also servant passages no longer interconnected with those of allied staffs as they once had. Such connections were bricked up, but they were still only a wall away in some cases, and if they had been reestablished in certain instances, no one outside a given household would likely know it until that apartment came up for reallocation. To this day, there was officially no interconnection between apartmentsc that anyone admittedc and there definitely was, if one read the records for hints. He had tried to explore all of the servant passages, but there were doors that locked, and one supposed it was part of security—but he had no key. That was inconvenient. There were stairs that went down a whole other level, and met a door, and he had no idea where that went. That was locked.

It was, of course, safer to have both guards and electronics. And it did seem that industrious security might have installed modern listening devices right at those points where passages had once connected. Some such devices the ship used had been very sophisticated at picking up conversations much farther than anyone would think. He would bet, in fact, that some things his father used would make it a good idea to do any verbal scheming well away from the Bu-javid.

But he was teaching his staff kyo and Mosphei’ for communication emergencies. He knew some of the Guild handsigns, and taught them. Antaro and Jegari had other signs they had used in hunting. They were teaching him those. They had their own language.

He was personally, too, getting much faster at skimming text in Ragi, in his library sessions: Antaro and Jegari scanned things so slowly and methodically—but he could find the word “passage” or “stairs” or “water” with one glance at a page.

It was curious, was it not? The word for electricity was that for fire in a wire. It was curious that the word for pump was really two words that meant stream and lift. Humans had given their technology to atevi after they had lost the War of the Landing, step by step, so as not to disturb the economy or wreck the environment, but atevi had not brought the human word across with any item until just very recently, when a few Mosphei’ words had begun to describe things like computer parts.

Interesting. Interesting. That change had happened during Bren’s service as paidhi. Bren had changed things, and let that happen, and the whole world had sped up.

And it had all happened during his father’s regime. Never before.

The technology had come in so fast, with computers and spaceships and all—it was like Cook’s bread when the yeast set to work. It was one little bit, and then it was huge, all of a sudden.

If Uncle Tatiseigi had been aiji instead, no Mosphei’ words would have gotten in at all, but his father had let it happen, and let technology just explode all over the place, because humans were taking over the space station and if his father had not gotten atevi their own shuttles, and trained the only pilots, humans would run everything up there. Now they shared the station with atevi, and atevi were even building a starship of their own.

But the changes down here in the world had upset a lot of people like Uncle Tatiseigi, and Murini had gotten a lot of those upset people together, particularly from the south and among Uncle Tatiseigi’s neighbors, to overthrow his father.

And what did they think they were going to do, then? Break all the computers and turn off the televisions? That would upset everybody else, who were not happy with southerners running everything.

Mostly the overthrow had let Murini sit in Shejidan and take revenge on his enemies before they got to him. Murini had never built anything or done anything good.

So the moment it was clear Great-grandmother was back from space and his father had help enough to take the government back, everybody ran out in the streets and cheered.

Who was related to whom had been a lot of boring lessons on the ship: it had gotten very interesting since they had landed, and he started wondering why his father let certain people get away with having supported Murini, while others ran for their lives.

His pocket dictionary showed hard use. He chased words through the thickets of very thick writing, sometimes looking up every major word in a sentence. But he learned what things had used to be true and where they came from. He filled long, boring hours with chasing needful words and following one word to its associates.

He found out how everything was put together—not just the pipes and wires and the servants’ hallways.

He found out what people on staff were likely to inform his father on him, and who might have a sense of humor.

And he swore to himself that there would come a day very soon when he found out events like Bren’s visitc oh, well in time to turn up uninvited.

5

The paidhi’s office had not quite opened its doors for business, down on the lower tiers of the Bu-javid, but electronically speaking, it had come alive last night, and Bren was ever so delighted to see it happen. The walls still smelled of fresh paint, the plaster was cold to the touch, still curing, but twenty-one computers were busy receiving polite messages from the provinces and the city, and a youngish set of technicians at another bank of computers, five in number, was busy feeding in every rescued file from the computers which Murini’s zealot reactionary supporters had destroyed—a destruction, one secretary informed the paidhi with immense satisfaction and amusement, well before Murini’s sole computer expert, a man with unfortunate southern connections, had had a chance to investigate them. Murini, who had a smattering of computer knowledge, had been beside himself.

But even so, the paidhi’s departing staff had wiped the disks clean before the zealots ever got there, with only two exceptions they could not reach, and those two computers Murini’s thugs had very obligingly not just bashed, but blown to small bits. At the very least, the number of people who could have become targets of Murini’s enforcers had diminished by thousands with that single blast of a grenade.

Meanwhile the loyal staffers of the paidhi’s office, carrying the storage media, had headed for remote areas. Some had gone fishing. Some had gone to powerful relatives, persons too highly placed to fear Assassins and too secure to regard any demand to turn over a member of their households. Some staffers, of lesser families, had simply slipped into allied households and vanished from all notice, retiring to family estates in the highlands or the isles. For every staffer there was a story, and some of them were epic. Bren heard one after another, while pizzas, sent up from the kitchens, disappeared. Meanwhile the computers kept blinking and restoring and storing.

“One is deeply moved,” he told the company, in a lull in serving and drink. “One is profoundly, forever bound to remember your actions. Within the year, the regime standing firm, one would wish to have all these adventures committed to print, with suitable protections for names that might not wish to be too public, and set in the library to be part of the history of the house. Above all the aiji should be informed what a brave and clever staff honors the paidhi-aiji with their service. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”

He bowed three times, to the whole staff, all around, who demonstrated great pleasure.

It was a happy gathering. The computers digested the flood of letters that came in to the paidhi, letters to be catalogued and answered, ranging from schoolchildren’s inquiries to matters of state. He had used to do it all by hand. And it had used to come only by post, taking days. Now it was minutes. They had yet to receive the physical mail, which would arrive in sacks and on trolleys, he was quite sure, excavated from post offices that had been physically shut down.

He enjoyed a piece of pizza. Banichi and Jago, on duty, declined to eat in public, but he shared lunch with all the staff, some of them eating with one hand and punching keys with the other. He had already told Madam Saidin that the refreshments in the office would constitute sufficient for the day– please God they had ordered enough food, as fast as it was disappearing. The capacity of some of these computer workers for food and drink was astounding.

Nuggets of information arriving amid the general flow of congratulations, he had received substantial letters, welcome news of escapes and survival among the Manufacturing and Transportation staff, news of associations that had held fast despite Murini’s hunting his people—there had been six of his personal staff brought to trial and one imprisoned. That man was released, recuperated, and on his way by train. Kinships, marriage ties, on-job associations, and all sorts of obligations– and his staff’s understanding of what records were precious. The University had suffered the most, and had been the target of immediate armed raids, but the students had gotten warning, as it turned out, from the paidhi’s staff. Consequently, the students had walked out with their library and the papers. Communication between his staff and the pilots at the spaceports had outright saved the aishidi’tat’s records and research in that areac not to mention lives. These people were heroes– every one.

“Nand’ paidhi.” One staffer came to him earnestly with a printout in hand, and bowed. “The Messengers’ Guild reports that Mogari-nai’s link has just gone up. It expects contact with the station at any moment.”

“Excellent!” he exclaimed, absolutely delighted—it was something he had hoped to hear for days; and now—now that the messages were beginning to flow unchecked, the Messengers’ Guild managed to get the dish up. Something had gotten their attention: he was not so uncharitable as to think they had been waiting for some more atevi request from members of their own Guild. “Excellent, nadi!”

And in that selfsame instant of triumph, he noticed an anomalous sight in the doorway, a smaller than average anomalous sight: Cajeiri had turned up, with his two young bodyguards.

Cajeiri had spotted him, too, no question, but made no effort to come his way.

He went to Cajeiri instead, a matter of precedences. The young rascal bowed, and he bowed. “Welcome, young sir,” he said. He had not invited the boy. It might have been the aroma of pizza, or the gossip of staff which had drawn him, and by his manner, the boy knew he was trespassing, junior lord of the aishidi’tat or not. “One certainly hopes your father knows where you are.”

“Oh, we’re at the library,” Cajeiri said pertly, and in Mosphei’, in a room where rudimentary knowledge of that language was not that rare. “We heard there was pizza. We haven’t had pizza since the ship.”

We in this case embraced only the young rascal, not his staff, who probably had never had the treat. “Well, you and your staff are welcome to share, young sir.” He persisted in Ragi. “Some people here can understand Mosphei’, you may know. And how are you faring? Are you doing well with your parents?”

“One is bored,” Cajeiri said in flawless, adult Ragi. “One is very, very bored, nandi.”

Banichi and Jago had noticed the boy’s presence. The whole room had noticed, by now. The party had greatly diminished in noise and impropriety, and hushed all the way to silence as Bren looked around at the staff.