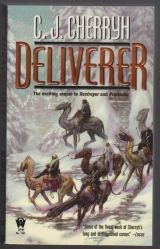

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Neighbors of the dowager’s estate of Malguri. Not the best sort of neighbors, Bren decided. And his chair was not too happily between Lord Tatiseigi on the right and Lord Caiti on the left. Never would he have thought to find Lord Tatiseigi the more comforting presence—but at this moment the old man was a haven of courtesy and kindness. Cajeiri was across the table, between his great-grandmother and Lord Rodi, a perfect model of young gentlemanliness and current Ragi fashion. It was chilling, the grim look on that young face when no one was addressing him: it transited to perfect affability and a spark in the eyes as quickly as ever his father could manage, as his great-uncle Tatiseigi addressed him and asked whether he had seen his mother today.

Little politician, Bren thought. Never mind “little” was as tall as he was.

“No, Great-uncle,” Cajeiri said quite cheerfully. “One is certain she is busy.”

“The boy does not reside with his parents, ’Sidi-daja?” Rodi asked Ilisidi bluntly.

“My great-grandson resides with me, at present, nandi, and has over the last two years,” Ilisidi said.

“For security,” Rodi pursued.

“Indeed, nandi,” Ilisidi said. What that extended exchange meant Bren had no idea, since dinner service began, the servants moving in, and conversation contracted to requests for the sauces, compliments for the cook, and, thereafter, discussion of the weather and the plane flight the lords had had, coming west.

Ilisidi did regale the company with an account of the weather on the coast and in the midlands and inquired after their estimates of the coming winter—suitably tame topics for dinner, notably boring, as Tatiseigi, a font of past meteorological data, somewhat tediously compared notes on recent winters with Lord Rodi’s recollections, two gentlemen living on one side of the continent and the other, and gave his theories about the predictive qualities of early leaf-fall.

It was actually the bright spot in the dinner: the two seemed to warm to one another, seeing they shared similar views.

Cajeiri ducked his chin and smothered an occasional yawn over the vegetables. He perked up at dessert, however, and took a second helping.

Bren had one helping of the custard, and rather hoped to escape before the brandy. He looked for chances. But there was absolutely no breath of a gap in the proceedings. It was outright impossible to present his excuses and leave when the dowager seized him by the arm and asked, “And have you been able to reach nand’ Toby today, nand’ paidhi?”

She knew the answer to that question. He’d bet his coastal estate on it. Jago had been using her staff’s equipment, no doubt of it.

“Regrettably I have not, aiji-ma.” As he found himself steered for the sitting room. “Though I am indeed pursuing it.”

“So. Well, well, my staff will keep trying, too, nand’ paidhi, in all good will.” This, as they passed the door into the more intimate setting. She turned and made an expansive wave of her cane, all the while maintaining her grip on his arm. “Lords of the East, share a glass with us, and my great-grandson will of course have a lighter refreshment. The paidhi-aiji has very graciously agreed to stay with us for the social hour. Do not hesitate to inquire of him or us, gentle neighbors.” She at least released his arm. “And how are affairs in the inconvenient snowy heights, Lord Rodi?”

Brandy made the rounds. Bren knew the server, at least, would be careful of his sensitivities. He took the glass and intended to claim a seat unobtrusively in the corner near the door, but: “We are bored, nand’ Bren,” Cajeiri remarked, at his elbow before he could achieve his objective. “Where is Banichi this evening?”

“A necessary meeting,” he said, and had a sip of brandy standing.

“He will be back soon, young sir, so I am promised.”

“There was an assassination this evening,” Cajeiri informed him cheerfully. “A Talidi lord. We forgot who.”

Jago had not told him that news. Possibly, considering the boy’s sources, even Jago had not heard it yet. “Was there indeed, nandi?”

“Yes, nandi,” Nawari reported quietly from behind his shoulder.

“Lord Eigun is dead.”

Eigun was a disagreeable man, a man he personally wouldn’t miss, though he was sorry for the news, on principle. Rodi seemed pleased, however, and he passed it on to Agilisi, who outright asked the dowager the details as everyone settled to enjoy their brandies.

“Cenedi-ji,” Ilisidi said, and Cenedi, her head of security, stood forth in the gathering and gave the more particular details: Eigun had been returning from a trip to the southern islands, probably fled there for his safety during the upheaval of the aiji’s return to power, and had returned too soon. It was doubtless Assassins’ work, a neat shot out of the morning dark. There were no other fatalities in that household, and no one knew whose order had sent the Assassin who had done it—if it wasn’t the Guildmaster’s own order, or a Filing approved by the Guild—likely not a recent one, since the Guild had been obsessed with its own upheaval in recent days—but the Bu-javid records were in a thorough mess, under intensive review. It was a nightmare, that there might be Filings floating around as relics from the former regime, with Assassins engaged, and Tabini’s administration as yet unapprised of their existence.

Not even mentioning the occasional in-clan assassination, when man’chi had broken down.

“Well, one happy event for our visit,” Agilisi said, turning a dismissive shoulder: there was insouciance in her tone, outright rudeness to her host, and arrogant disregard of other possible opinions or allegiances presentc when it was very likely Agilisi had no intimate knowledge of western connnections.

“We never met him,” Cajeiri remarked, frowning. He had walked over next to Bren, with his fruit juice, and a small mustache of it on his lip. “Was he indeed a bad man, Great-grandmother, and should one indeed be glad?”

There was a very uncomfortable moment. The boy had learned his manners on the ship, where he knew the undercurrents to a nicety. Here—was another story. But he had just rebuked the lady and deferred to the host with an accuracy that made Bren’s heart skip a beat.

“We hardly knew him,” Ilisidi said smoothly, and redirected.

“Does the paidhi-aiji happen to know his character?”

A chance, a palpable chance to salve the Eastern lady’s provocation and the heir’s jibe with diplomacy—or to provoke the lady in a way that would be very unprofitable to the dowager’s relations with her neighbors.

And, professionally, he gave a shrug and avoided eye contact with the Eastern lady, answering the dowager’s question in a deferential way. “Having been absent so long,” he said softly, “we find ourselves inclined to reserve all judgments: recent events have reshaped allegiances. The paidhi-aiji would far rather consult those who might be better informed.”

“And who would those sources be?” the belligerent lady asked, ignored. “What authority does a human ever consult?”

Now he had to look in her direction, and bowed, politely and respectfully—before firing back, softly: “One consults the aiji-dowager, of course, nandi, in all matters.”

“Perhaps,” Lord Caiti said, out of the breath of shocked silence that followed, and gesturing with the empty brandy glass in his hand, “perhaps the paidhi will elucidate on matters he should indeed actually know something about: machines from the heavens.

What are they, and what business do they have settling on our land?”

Landed in the East as well? That was news. And it was not a polite question, not the way it was stated.

“One has had rumors likewise from the north,” Bren said smoothly. “Any such landing in the East is news to me, though certainly not out of all possibility.”

“As if it were nothing? We have destroyed them where found! We assure you of that! And in the north as well? What are we, raining infernal machinery from that pernicious station?”

“My office must confess ignorance in the matter, Lord of the Saibaitet Ami. Our passage through the station at our return was much too rapid to gather all details of what the station lords have done or caused to be done during the dowager’s absence, but one assures the gracious lord that if there was such a landing within his district—”

“Repeatedly!”

“Then I can only surmise the intention was both benign and possibly of service to you, if indeed, the package came from orbit and was intended to be set where it came down.”

“You impugn our common sense? What do you take us for?”

Bang! went that formidable cane. “Caiti, Caiti-ji, the paidhi-aiji is telling you what he knows, which is, we assure you, no more nor less than what we know: that fools in the south instigated all manner of trouble in our absence, that murder was done under this very roof! That Lord Tatiseigi’s neighbor, who has been repudiated by his own clan, has acted quite foolishly, and that the paidhi-aiji, Lord Tatiseigi, my grandson, my great-grandson and I have all spent so much time being shot at that we have not investigated strayed items dropped from the station—as the very least of concerns in Shejidan! These things were parachuted down possibly to reconnoiter, possibly to map, who knows? The installation at Mogari-nai is under repair and we are unable as yet to inquire of the station aloft their reasons for such landings. But we assure you the station acts consistently in support of Lord Geigi, among others, in any such mission undertaken to the mainland, and subject to his will. Lord Geigi, whom we left in authority on the station is still in power on the station, was never overthrown in the general disorder here in Shejidan, and he to this hour enjoys great authority over any such operations aimed at the planet, let me assure you, Lord Caiti. I certainly hope you have not destroyed some installation which would have monitored rebel aircraft encroaching on your province. That would be a misfortune.”

“I have every right to destroy whatever foreign object falls on my land! Whatever foolishness you pursue here in the westc”

“Pardon me, nandi.” A high and indignant voice intervened. “This is my great-grandmother’s house, and,” pointing at what Caiti held, “that is her brandy glass.”

There was stunned silence. Then Agilisi outright laughed, and Rodi smiled, silently, behind his hand.

Caiti looked at the offending glass as if he hardly knew whether to fling it at the floor or set it conspicuously on the side table.

Security all around the room was braced, hands not moving, but close to it.

“You trust my brandy,” Ilisidi said quietly. “As indeed by my good grace you may, Caiti, you scoundrel, and you know you may trust our brandy and our opinion. Rodi and Agilisi at least have no doubts of my intentions, nor have deserved to have. You share my hospitality with the paidhi-aiji and my hot-headed great-grandson, and of course you have questions in our return to the world, but grant we have moved with too much speed to pause for detailed briefings. Tati-ji, we ask your indulgence for our esteemed neighbors: they know us; we know them, oh, intimately. Patience, I say, Cai-ji, and do sit down.”

“Disagreeable woman!”

“Dare you?” Tatiseigi broke in, dignified and lately glorious in battle. “Dare you insult your host, nadi?”

Oh, it was about to get bitter. “Nandi,” Bren said, concentrating his gaze on his waterglass, “do allow the aiji-dowager to make peace, one most earnestly entreats it.”

There was an audible huff of breath, but the old man sat down.

Cajeiri went to stand by his great-grandmother, right by Cenedi, and entraining his own unofficial security as he did so.

“Now, now,” Ilisidi said, reaching for the boy’s hand. “Defense is unnecessary, Great-grandson. These are my neighbors, my esteemed neighbors around Malguri. They are inclined to speak bluntly, but they are not fools. Caiti has been a valued associate in prior years. And—” The latter in a low voice: “remember what is done here, in your own time.”

“Ha,” Tatiseigi muttered, with a look like a jealous lover. He positively youthened as he glowered at the three Easterners.

“Foolishness, foolishness,” Ilisidi said. “Let us have a civilized agreement, shall we? As for Lord Bren’s presence, it now seems very wise to have asked him to favor us with his attendance tonight. Would you not agree, Bren-nandi, that whatever was landed in the East was likely done with Lord Geigi’s consent? And Lord Geigi is out of the Coastal Association, long correspondents of the East—an old, old alliance, his with Malguri.”

“If the ship-aijiin acted otherwise and failed consultation with Lord Geigi, it would breach all manner of agreements,” Bren said, “and I would be obliged to carry strong words to the ship-aijiin in protest. I hardly believe they would have done so. But even if there had been some misunderstanding, take reassurance in this, nandiin. Two ship-aijiin have returned to the station aboard the ship that brought us, and they are extremely well-disposed to the aiji-dowager and her interests, having spent two years in her close association. The third, Ogun-aiji, whatever he may have done good or ill in his administration of the station, must now account to them for all he has done in their name, and I have no doubt he will do so.”

“So there is disagreement in the heavens, and they drop machines of war in my woods!” Caiti cried.

“Nandi, one is certain that there will be adequate explanation and accountability for any actions taken in the aiji-dowager’s absence, to your ultimate satisfaction. And one is equally certain that none of these actions were aimed at all at seizing advantage for the ship-humans, or aimed in any wise at securing a foothold on the earth. One is very confident that any machines dropped from the heavens have been in support of legitimate atevi authority, most probably to secure communications for the aiji’s forces when he might need them.”

“Communications to do what?” There was no polite address. It was entirely rude. “To make us a battlefield? No aiji of the west has ever set foot in the East.”

“No such thing, nandi, but the ship-folk will have wished to preserve your ability to contact the aiji’s forces, should hostilities break out. One is most regretful that such a gesture could have been misconstrued.”

“Misconstrued!”

“Nandi.” A tap of the dowager’s fingernail against the empty brandy glass, a clear, crystal note. “One may not lay the deeds of the station in the paidhi’s lap, certainly not if you wish his good offices to lodge inquiry on your behalf.”

“We expect an explanation.” There was a small silence, and the old lord muttered, “Nandiin.”

The plural was generic. It did not necessarily include the paidhi.

But it might. It did not, however, properly respect the dowager.

No sense pushing it, Bren said to himself.

“Doubtless,” he said, “we will learn the answer, once communication with the station resumes—which it has not, nandiin, so whatever the station-folk have dropped, they have not activated, or we might not have these problems in reaching them.

One rather thinks they have not activated them, in deference to the dowager’s efforts and the aiji’s return to the capital. They would not wish to offend sensibilities.”

It was not a damned bad speech, impromptu as it was. Its numbers were convolute enough to keep the restive Easterners calculating and digesting the information for a few heartbeats at least.

“Well,” Agilisi said with a ripple of thin, manicured fingers, “well, well, accountability in the heavens. That would do a great deal to settle our stomachs.” She finally sat down. So did Rodi, and Caiti settled, still frowning.

“Sit down, Great-grandson,” Ilisidi said with a little pat of her hand on Cajeiri’s, which rested on her chair arm, and Cajeiri finally went and took the chair by Lord Tatiseigi. A servant quickly offered him a refill of fruit juice. The servants moved in general to pour more brandy on the situation, and for a moment there was an easier feeling in the air. Caiti took a very healthy dose of brandy—whatever its effect on his common sense.

“Well,” Caiti said then, “well. Machinery falling out of the heavens. High time the dowager attended to her estate. When will you visit us, ’Sidi-daja?”

“Oh, soon. Soon.” Ilisidi took her own glass, refilled. “Those who thought our being sent to space was our grandson’s means of being rid of us were quite wrong. We are back, nandiin-ji. Believe that we are back.”

“Oh, there were far worse rumors than that, ’Sidi-daja,” Rodi said. “There were immediate rumors you were being held prisoner in Shejidan or on the station, there were rumors that the humans on the station had joined Murini, or that you had long ago died in space and no one would confess the fact, while humans corrupted the aiji’s heir.”

“A pretty fantasy,” Ilisidi said, and smiled. Her eyes did not.

“Surely Murini hoped so. But we thrived. We succeeded. The aiji’s heir is quite uncorrupt. He rides, he shoots, he ciphers, and he is conversant in the machimi. And here are three of my neighbors come to threaten our glassware and wish me a fortunate homecoming. What could we lack? But where are Ardija and Ceia tonight?”

These were two other districts of the East, major holdings not represented here: Ardija was actually closer to Malguri than, Bren recalled, Caiti’s holdings at Torinei, in the Saibai’tet Ami.

“We came in respect of the aiji-dowager,” Caiti said flatly. “We chose to come.”

“Well, well, and Lady Drien of Ardija and Lord Sigena of Ceia did not. Ah, but perhaps they had a previous engagement.”

“One doubts that,” Rodi said under his breath.

Ilisidi nodded sagely, contemplatively. “Your attendance at our table confirms my judgment of you. We shall not ask about Sigena.

We are not on the best of terms. But our neighbor Drien? I am somewhat disappointed in Drien. One would have expected word, at least. Can kabiu have failed her?”

There was a restless shift, not quite glances exchanged, but uncertainty.

“We do not judge, nandi,” Rodi said. “But we are here.”

“Guard yourselves, the while, nandiin,” Ilisidi said. “Households returning are just now settling, and the capital is still in turmoil.

One should take great care, coming and going to the hotel tonight.

As for that scoundrel Murini, Tati-ji, have you any recent information?”

Tatiseigi cleared his throat. “Reports state he has landed in Talidi. Who knows, now, with this assassination? Perhaps he is behind it. Perhaps he will move on, fearing retaliation. We have not heard word of Lady Cosadi, who has dropped entirely from sight.”

“Perhaps the aiji is already settling old scores, nandi,” Agilisi remarked.

“Not quite yet, nandi-ji, in her case,” Ilisidi said. “One believes she is hiding. And you will find no one in the north will mourn Talidi moving against each other. Murini himself may not survive this settling of old scores—if he is not behind it; and if he is, then one may lay odds others will deal with him without the aiji’s turning a hand. There will be a certain repaying of old debts all through the south. I should not be surprised. I should not be surprised if Lady Cosadi now finds Murini an embarrassment. But clearly she will not live long, and her own followers may be thinking of that. Twice spared, twice made a fool of in her choice of causes, and I believe my grandson is entirely out of patience.

Others certainly may be.”

Fruit juice was a treat after their long voyage, on which even tea had run short. Cajeiri sipped it the way the adults did the brandy, out of the special glasses, as he kept a careful watch on Lord Caiti, and nand’ Bren, who had answered the Easterners’ bad manners very sharply and very correctly. Great-grandmother was keen-edged tonight: it was something to watch.

Reminding Lord Caiti who provided the drinks had been a good touch on his own part, too. Cajeiri was very pleased with himself, and with the way great-grandmother had taken it right up. She had already told him about Caiti: more mouth than thought, Great-grandmother had said, and she was right. Rodi was smart, and said very little. Agilisi was probably the one to watch in this set, and just occasionally she looked curiously distressed, as if she was not entirely happy with the evening.

The people they talked about—Sigena was to the west of Great-grandmother’s estate, and a perpetual problem. Drien was closer, and more so, being upset about some old land dispute right on Malguri’s edge. Drien was great-grandmother’s youngest and only surviving cousin, and her not being here tonight had certainly raised great-grandmother’s very ominous left eyebrow. He wondered if these three had known how to read Great-grandmother’s expression—it had left him a little confused.

They were all Great-grandmother’s neighbors, and their numbers, combined with Great-grandmother alone, were not felicitous—they would have been felicitous, had Lady Drien come, but they added badly, without, and cast the balance-making to Great-grandmother’s good will, to make up the rest of the table. So she tossed in not one, but three of her own asking for dinner; that saved the felicity of numbers, but he thought the visitors might have hoped for his father and mother and him to be sitting here instead of Lord Bren and Lord Tatiseigi.

So they were surprised to find Lord Tatiseigi, who was too kabiu to quarrel with, more kabiu than they were, if it came to that, in their coming here all but demanding a dinner—the proper thing to have done would be to write from the East hinting they wanted an invitation: that would have respected Great-grandmother’s rank, but they had not done that. And they kept calling her not nand’ dowager, but ’Sidi-daja, which was about like yelling “Hey, Gene!”

in Great-grandmother’s hallway. Great-grandmother said they were both more kabiu and less respectful of western offices in the East, but that seemed pushy of them, especially considering they were pushy in coming here.

So if he read the clues, it was not a happy meeting, and Great-grandmother had shoved her closest associations and particularly nand’ Bren right in their faces. That was the way Gene would express it, and it fit. Right in their faces. He liked that expression.

And they were powerful, all three together, but they were not that important in the affairs of the aishidi’tat. Lord Sigena had been, but he was not here. Drien had kabiu, but not a great force.

It was a dispute in the East whether it was kabiu to have Guild, which was a western institution, but Great-grandmother had, and for that reason a lot of the East walked very quietly where Great-grandmother was involved. How dangerous those bodyguards over there were—he would pick Cenedi and Jago over all of them together, he was quite sure, but alarms were still ringing, in the barbs flying back and forth, and he sipped his fruit juice and kept trying to add things in his head, who was barbing whom, and most of all why Great-grandmother put up with it.

Because they were neighbors? Because they were all Easterners?

He had memorized all the provinces and their lords, all the provincial estates and the holdings in all the aishidi’tat, including the Eastern districts in which Great-grandmother’s heredity meant property, and rights, and obligations that stretched on into very long ago, until he yawned and Great-grandmother thwacked his skull and asked him to recite it all back. Great-grandmother had thumped the details into his head over two long years, along with the machimi, a grasp of poetry, and the laws of inheritance, property, and bloodfeud.

He knew he was actually very, very remote kin to Lady Agilisi.

He was not sure he liked being. And he was more kin to Drien, whose absence Great-grandmother found interesting.

And the news about machinery dropping out of the sky onto Lord Caiti’s lands, that had been an exciting point, and he wanted to know more about it. He had ached to inform Lord Caiti he was a fool for breaking what was probably very valuable and useful equipment, but Lord Bren had handled the man well enough.

Now it was just talk. And talk ran down to actually polite discussion over the third round of brandy, naming names, some of which he knew. They talked about Malguri, which was Great-grandmother’s estate, and she was glad to know it had not been bothered during Murini’s rule.

So was he. He had never been there. She had kept promising him—or threatening him with a year there, where she informed him there was no television at all. He thought it would be interesting to see, but he wanted not to be left there.

So, well, grown-ups were in charge of the evening, and there was more and more talk, and things grew boring.

Then deadly boring, as they got down to babies and births, which he tracked, because he was absolutely certain Great-grandmother was going to ask him. He had to memorize who was related to whom, particularly those that were related to him, and he tried.

But the back of his thoughts took comfort in the fact underlying all this conversation, that the guests were leaving Shejidan in four days, going back across the mountains, and he really, really hoped there would not be another dinner party before they left More boring things. He watched their security, wondering what they were. At the very last moment, arriving for the dinner, Great-uncle Tatiseigi had provided him two Guild Assassins that loomed over him and Antaro and Jegari. He had left them both in the outer hall, but they would be coming and going in his apartment, and he really had no choice about it if Great-uncle was going to insist. They were Atageini: they were substantial protection, Great-grandmother had said this evening, making it fairly clear he had to take them, and he had gone so far as to mutter that none of Great-uncle’s men had done very well about defending them this far, which his Great-grandmother called ingratitude and impudence, and said he should never, ever say that to Great-uncle.

So he had to thank Great-uncle for sending two people he had as soon not have spying on him.

Because he was sure that was exactly what Great-uncle was doing, and Great-uncle had picked this evening to slip them into Great-grandmother’s household. They were nowhere near as good as Banichi and Jago, and they were probably not happy to be assigned to him, either, they were glum fellows, in their middle years, and had no sense of humor, if looks said anything.

More, they were Atageini, and Atageini were not on good terms with Taibeni folk, not for centuries, and the recent alliance had done nothing to patch up personal feelings. They clearly looked down their long noses at Antaro and Jegari attempting to protect him, not only because they were not really Guild, and Guildsmen took a dim and jealous view of non-Guild trying to do their job, but also, he strongly suspected, just because they were Taibeni. Antaro and Jegari had gotten respect even from Lord Bren’s staff. Banichi and Jago had said, had they not, that they were very brave?

He feared he was losing certain elements of the conversation. He tried listening and remembering, but it was just more names that meant nothing to him. He had a notion he could ask Great-grandmother later and get a long, long explanation which he would have to remember.

And he intended to find every excuse to leave the Atageini guards standing in the hall at functions like this, until they got the notion they had to please him in order to get permission to do anything else.

If they got bored enough standing in the hall, they might go back to Great-uncle and beg off. Then he could talk about them with Great-grandmother and maybe get rid of them altogether. That was a plan.

He could get Antaro and Jegari into the Guild; they could start their schooling. Banichi said they could, and he would back them.

And that would mean they would be gone some of the time, and the Guild had a lot of things to decide before they got around to two youngsters from Taiben, but it was going to happen, was it not?

But that might mean he had Great-uncle’s guards on his hands all the while they were in training, which could be years. And years. And years.

That was just—Gene would call it—gruesome.

He would still have them stand in the hall, until they knew to take his orders.

But Antaro and Jegari had to go to the Guild. They were not cut out to be domestic staff. He knew that. They were rangersc well, they had been trying to be. They knew guns, and hunting, and trackingc “Well,” Great-grandmother said, in that particular way that made all her guests know that the social hour was about to end—and he paid attention. It was very effective, that well, and had to be a particular tone, with the look and the attitude. Cajeiri had practiced it himself in private.

Great-grandmother, however, wielded it with expertise and her guests never dared take offense. She simply said, “Well,” and in due time the guests got up and finessed their way to the door as if they felt apologies were due on their part for leaving: it was very curious how that worked.

And it came very welcome.

He got up, too—Lord Bren found his way out, and Cajeiri decided there was no particular reason to bother adults with a good night.

He was only wishing he could shed his lent Atageini clan bodyguard with a similar lack of offense. “Well,” would not be adequate.

But he ever so much wished he could have somebody else.

“Jeri-ji,” Great-grandmother said.

“Mani-ma.” He bowed, offering that intimate address. “Excuse me.” He had been caught inattentive. He had no wish to be found at fault, and bowed again to Lord Tatiseigi. “Great-uncle, thank you very much for lending staff this evening. I will return them with profound gratitude when things are settled.”

“They will remain here,” his uncle said dourly, with that lack of address only acceptable when one confronted a child. “Your mother will call on them at need, with her own staff.”

“Yes, Uncle,” he said, wondering what his mother’s need of staff had to do with anything, but uncle could be at least as indirect and as scheming as his great-grandmother.