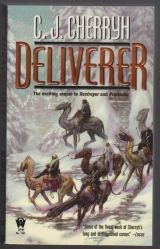

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

If only, if only, baji-naji, they believed those lying footprints.

Breathe. Breathe, as much wind as he could get, and try not to cough, try not to make noise. Bren had no idea where Banichi and Jago were, except he’d bet, ahead of him, considerably, though his was the shorter route, along the lake shore.

Run and run. If help was coming, there was no sign of it, and when, in a moment he had to stop to ease the pain in his side, he snatched a shielded look at the locator, he saw he was closer to that box on the map, the structure, the fueling depot, whatever it was.

And thus far no shot fired, no sign of parties stalking one another, and he hoped to heaven Banichi and Jago were in fact ahead of him, not veering off to try to make immediate contact. He left it to Banichi’s sense whether to try to use the unit-to-unit function on the pocket com: if Banichi or Jago called him, he’d use it, but not trust it otherwise. He only kept moving, watching the woods and the orchard edge carefully for any sign of life, and not, as yet, seeing anything. He would be unwelcomely silhouetted against the lake if he grew careless and took the fastest, smoothest course. As it was, he climbed over snowy driftwood and skirted around brushy outcrops, terrified as he did so that he could himself fall into ambush—whoever was tracking Cajeiri would be almost as happy to lay hands on the paidhi-aiji, for revenge, if nothing else, and he was determined to make a fight of it if he had to, but to avoid all chance of it if he possibly could.

Bare spot in the woods, something, for God’s sake, akin to a private yard, and a set of steps and a boat dock, such as it was, a mere plank on pilings, and a rowboat turned over and beached on the shore, up on blocks for the winter, as might be. He got down by it, said, quietly, foolishly, “Cajeiri?” in remotest hope that the boy might have taken cover in that shell, and the snow have covered his tracks.

No answer. Nothing. And there was no way Cajeiri could mistake his presence. He edged away, keeping low, and filed the location of that boat in memory.

Escape, for him and the boy, if he could lay hands on Cajeiri first.

A way out. He formed a plan, if Murini’s lot was still rummaging about the areac if that bus was not out on the road, if Banichi and Jago were up there somewhere reconnoitering the situation.

And if shots were not being fired, either they had not made contact with their enemy, or, most terrible thought, they were altogether too late to intercept that bus out on the north road, and Murini and company had already laid hands on the heir and spirited him off toward one of the two airports.

If that was the case, it was going to be damned messy at the other end, and they had to hope that the dowager had gotten Guild into position up– He stopped, froze, with a brush-screened view of an ordinary house in the middle of that yard, the answer to why there was a rowboat up on blocks on the lakeshore.

A country house with two figures standing on the small back steps. He very carefully subsided into a crouch behind a log edging, trying to stifle his breaths, keep them small and quiet.

That wasn’t Banichi and Jago. Not a hope of it. That was Guild, plain and simple, that segment of the Guild, southerners, who had supported Murini’s takeover once, and had declined to come in and bow to new leadership.

So the house was occupied. Plain and simple. An enemy was in it, and one could assume it was the same they had been following.

He didn’t think Banichi and Jago were going to go blithely up to that door. He hoped to God they didn’t have Cajeiri in there, but he couldn’t bank on that hope.

The log that he sheltered behind lay, snow-covered, on the edge of the yard, as if it and the ones beyond it, all in a row, had been put there to make a fence, or stop erosion—lake waves must have gnawed this edge in storm; or rain had washed the earth down. It gave him cover. He could see the men on the porch, standing out there, as if deliberately to advertise their presence, or to draw fire, and one could bet they were wearing body armor.

Beyond the house, through a veil of light snowfall– Beyond, toward the front yard of the house, was the damnedest thing, as if there had already been a battle there, ruined trees where the orchard abutted the yard, and a structure that might have been some round bin, maybe a water tower, all down in a welter of girders– The men on the porch went back inside, and others appeared at the edge of the front porch, just visible.

Damn. Swarming with people. And no clue about Cajeiri. No movement from Banichi and Jago, either. He could not have outpaced them, no way in hell, and there had been no shots fired.

They were out there, seeing what he was seeing, laying plans of their own, he had no doubt in the world.

What he had, while those men were in the house, was a modicum of cover, which might let him get a vantage here, from the edge of the lakeshore, that Banichi and Jago were not going to have, to set up a crossfire, and maybe convince the southerners that there were two forces, and that it was time to run for it.

He edged along, downright crawling on his belly, under the cover of the log and its neighbor, to the small gap that allowed shore access, and a worn path out to that flimsy dock and the rowboat.

God, if only—if only Cajeiri had gotten this farc There was, edging the yard on the other side, screening it off from brush, a drainage channel, that let out right onto the shore, with an eroded, snow-filled gully, at the base of a low stone wall that edged the yard—he could see it, a low, inconsiderable wall that mostly blocked the brush that grew there, and just beyond that, a huge rock face, that ran right out onto the beach, the start of the cliffs that rose to Malguri’s height.

The rowboat was only one place a person his size could hide. A brushy ditch was another.

He made a fast crossing of that eroded path, and crawled on along the line of logs toward that ditch.

Footprints there, men’s footprints. They’d been down this way, searching. They’d been all the way up and down the shallow, stony ditch. And with the overgrowth of brush, the last thing he needed was to disturb the brush overhead and have it seen from the house.

Just– Mechanical whine. A sound from the ship. An out of place sound that scared hell out of him and froze him in mid-move. It went on, from the far front corner of the house, and imagination replayed the wreckage up there, the destruction. What in hell? he asked himself, and then memory sorted out the lines of that collapsed tower, and replayed Lord Caiti at dinner, arguing about– —landings.

God only knew. Something was going on. The occupants of that house were likely distracted—it was a chance to move, was all, whatever else was going on, and he crawled up into the ditch and kept crawling, while the hydraulic whine went on and shots broke out, wholesale firing.

Crawl like mad, trying not to disturb the brush. He was out of breath. And the hydraulics reached a rhythmic, interrupted regularity, thump, thump-thump, as he hung up on a branch and tried to free it.

Hell with it, they had to be busy. He forced his way past, never mind the shaking of a branch, and moved faster, faster.

Crash, splintering of wood, firing like crazy, and he could hardly stand it, but he kept crawling, his elbows sore and his knees and feet frozen, face scratched from branches. He was hopeless if they came back this way—he was trapped between the rock and brush of the cliff and the rock of the stone wall. It was a stupid thing he had done, but it might lead him up to the road, where if they had Cajeiri, he might get a vantage to pin them back into that house until help could get here—there must be help coming. The dowager would see to it—she would turn out the whole of Malguri Township to help them. It was not just himself and Banichi and Jagoc Hydraulics kept up. Thump, thump-thump—interspersed with fire and voices. He reached a nook in the cliff on his left, a snowed-over spot where brush was thick, and there was not even storm-light to see farther down the ditch. He took advantage of the dark area and an overhang of brush to put his head up and try to get a look at the house and what was going on.

A whisper of movement behind him. He spun flat against the wall and made a foolish grab for the gun in his pocket.

“Nand’Bren!”

Boyish whisper. His heart thumped, heavy as the thing in the yard.

“Cajeiri? Damn, Cajeiri?”

“One is very glad to be rescued, nandi.”

Rescued. Rescued, in a ditch, pinned against a cliff, with a firefight going on and something on the loose out there.

He managed to breathe. “Get over here,” he said, rude outright command, and the brush moved, and a figure no bigger than he was came wriggling out from the roots and the rocks.

His immediate impulse was to grab the boy and hug him; he restrained it, contented himself with laying a firm grip on the boy’s parka-clad shoulder to be sure that young head stayed down.

“Banichi and Jago are out there on the other side of the house,”

he said, and thought of that boat, down at the other end of the ditch and along the shore. “Go ahead of me. Hurry. Down the ditch.”

Probably, he thought, no damned oars. People took that sort of thing into storage for the winter. That was a flaw.

But the boy moved, crawling along in front of him. And the shooting came their way, and that thing, going thump, thump-thump. The boy crawled for all he was worth, and he did, never minding disturbance of the brush.

Now the thing was closer, and the shooting was. It came right up against the wall, a towering dark shape flashing with lights, blotting out the sky.

Lander, hell! he said to himself, and Cajeiri reversed course as stones fell off the wall, a tumble of the first tier of mason-work, before the thing made its turn and simply limped away, thump, thump-thump. Bren levered himself up for a hair’s breadth glance over the wall as it lumbered on its way, and Cajeiri got up beside him. He put a hand on Cajeiri’s head and shoved him down, seeing, God, a monster, a mechanical monster, a cylindrical tower on three legs, a fourth one clanking and bent askew as it headed past the house. It misjudged, lurched, and took the corner of the front porch, which came crashing down in a crack of broken carpentry.

Stay put? Make a break for it down the ditch? He had no idea what to do.

His pocket com vibrated, like electric shock.

He grabbed it out of his pocket, flipped it open, and ducked low, back against the wall. “Who?” he asked.

“Btayi! Aeit eiga posii!”

It took him half a second to realize that sharp, clear tone was Jago’s voice and a heartbeat more to recognize and translate the out-of-context language. Kyo. Uncrackable by the southerners.

“Aeit makki.” Vocabulary eluded him. Wall. What the hell was wall? And how was she coming through that clear? “Topik! Aeit topik! Punjo’kui. Uwe aik haeit!”

“Kaie.”

She knew now where they were. We’re all right, he’d said. And: Don’t come here! because he and Cajeiri were safe where they were and man’chi would surely pull her and Banichi to risk their necks to get to him—Guild-instilled discipline might dictate something else, which was why they’d kept going when they had gotten separated, but come to him, they would, if he called, and he didn’t have any such– Something exploded, out beyond the front yard, an eruption of fire through the trees, illumining the orchard, highlighting the damned lander that was still thumping about in the wreckage of the porch as if it had gotten completely confused. That was their relay. That might even be driven by the station.

Then something major blew, and a fireball the size of a bus ballooned up, casting the far end of the yard in light, illumining the trees, and the wreckage. Pieces of metal began to come down, one heavy lump slamming down like the fist of God, right in front of their position.

Cajeiri popped his head up. He grabbed the boy and held him flat as a piece of sheet metal fell down right over them, providing cover, but near deafening them with the impact on the rocks.

“Ow!” Cajeiri breathed.

“Are you all right, young sir?”

“One is crushed. My leg—”

“Some vehicle blew up on the road,” he said, out of breath, and, hearing shouts and gunfire break out, he got up on one knee, struggling around past the piece of metal to get another look over the wall.

A dozen or so of someone not theirs was coming toward them, and in the light of fires touched off by the explosion, he saw Guild uniforms. He fumbled into his coat pocket, laid his hand on his gun.

“Get out,” he hissed at Cajeiri. “Get down the ditch to the lake, go left, and keep going.”

“Left, nandi! Right is—”

“Gods unfortunate, go!” No time. He opened fire at the one in civilian dress, the only one not going to be armored, as Cajeiri scrambled to do as he was told. That man dropped, the onrushing mass balked, several moving to retrieve the fallen man, and the lot veered off to the back yard, dammit, in the very direction he’d just sent Cajeiri. He fired three times more, at legs, which also weren’t armored, and hoped to God he was right which side was which.

He scrambled down the flagstone ditch, gun in hand, as fast as he could, while shots blew chips off the rocks and the stones of the wall over his head.

Second heavy explosion. He heard the lander thump, thump-thumping down the yard, and fire pinged off something.

“Halt!” a voice yelled, amplified and echoing off the rocks. “Halt!”

Fire redoubled. He reached the end of the ditch, and just slid off the eroded end of the drainage, trying to make speed and just get the hell wherever Cajeiri was.

Hands grabbed his coat, hauled at him. Cajeiri had found him, and he flung an arm around the boy and dragged him up and behind a jut of rock, while fire and light exploded—the whole damned house was afire, now, and the lander stood outlined against the surrounding woods, blinking with lights and threatening.

“Shall we run?” Cajeiri asked.

Good question. Dive out there and risk getting spotted, or continue to try to be part of the rock? He didn’t know what to do.

“Nand’ Bren!” Cajeiri exclaimed, and grabbed his sleeve and tugged him around to look at the lake.

There was a boat coming in. There were two boats. Three. None of them were showing lights, and they were coming hard.

“There is the greatest chance,” Bren said, as calmly as he could, “that they may be from Malguri, young sir, but it would be foolish to rely on it. Stand still. Let them come in. We may find that ditch a good retreat after all.”

“Yes,” a tense young voice answered, very properly, and Cajeiri stood like the rock itself as those boats came close, and veered off toward their end of the icy edge, and with a roar of the motor, ran around. Men in Guild black got out, and one, shorter, faces of all of them lit by the blaze of the burning house up the slope.

My God, he thought. My God. “Tano? Algini?” he called out. And most improbably: “Toby?”

They came running, all of them with rifles, Tano and Algini with a deal more gear than that, and Bren patted arms, that irrepressible human impulse, and outright hugged Toby, atevi witnesses or not, hugged him for dear life.

“God, Brother! What are you doing here?”

“Message said you were in the soup again,” Toby said, a return embrace nearly crushing the breath out of him. “They weren’t wrong. Who blew up?”

“I don’t know.” He changed languages, or meant to, but Tano and Algini had already headed off, likely on unit-to-unit with each other, and, he hoped, with Banichi and Jago somewhere up above.

He put the safety on his gun and tried for his pocket com, hoping to find out.

“Hi, there!” Cajeiri said to Toby. “I know you!”

“That you do,” Toby said. “Glad you’re safe, nandi.”

He got the pocket com, held it to his ear, heard, blessed sound, Banichi’s voice telling Algini and Tano they were a shade late, but they could come in on the yard.

Then Jago’s saying, “Murini is dead. His man’chi is broken. A bullet found him, and the Guild attending him wish to withdraw.”

“They will report to Headquarters,” Algini said then. “They will leave all weapons and turn up at Guild Headquarters, or be hunted .”

“They wish to take Murini to the Taisigin Marid,” Jago said.

Not even to Murini’s own clan, the Kadagidi, Bren thought. That said something.

The last throw made. The final try. The rebellion was done.

“We need to notify the dowager,” Bren said. His heart rate, which had hammered away for the last hour, began to slow, the strength to run out of him, and he was aware of knees battered and bruised, palms not much better, and a keen desire to sit down right where he was and not hear anything explode for the next while.

“We’ve got a radio in the boat,” Toby said.

“What in hell are you doing here?” he asked.

“Well, Tano and Algini had found us, and then the message got there, about the aiji’s son, and you going after them, so they just gave orders at the airport, refueled in Shejidan, and we came straight ahead from there. Too late to overtake you. But when the dowager’s man phoned Malguri for help, we went down to the boats. They’ve got help up there in the other fortress—”

“The Haidamar. The riders got there?”

“The whole lot, help from the other neighbor on the lake—”

“Lady Drien. So they’re all right?”

“Seems they are. But the boats were the quickest way across, and I figured I might be useful. If there’s one thing I know—”

“It’s boats,” Bren said, and became aware of a pair of young ears following all of it, but not necessarily understanding every word, in a world that was no longer the ship. “Nandi,” he said in Ragi, “your great-grandmother seems to be safe. Cenedi called Malguri and got help across the lake. We are safe. We can take the boats back to Malguri dock.”

“We would very much like supper,” Cajeiri said. “And we would be very glad if Great-grandmother came across the lake, too.”

17

A glass of wine for the grownups, and tea for the young gentleman.

Malguri staff, at full strength, having drawn up additional servants from the township, bustled about breakfast, which looked to be an all-out affair, on short notice. Cajeiri and Jegari had gotten together, Jegari with his arm in a sling, which had gotten considerable respect from Cajeiric and an enthusiasm from the young gentleman which had thoroughly embarrassed Jegari and gotten a reproving Look from his great-grandmother.

Bren just held his cup in newly bandaged hands and was very glad of the ice bag on his right knee, the foot propped on a footstool, and both his worlds being very hale and well this morning.

Toby—the odd man in the scene—had brought along his fishing-trip best, a clean khaki coat and clean denims, but another plane had arrived in the last confused hours, finally bringing the luggage out from Shejidan, so there sat Toby, looking a little uncommonly short-haired in a gentleman’s proper lace shirt and morning coat, but very proper, all the same, and very much cosseted by the maids. Tano and Algini were huddled in a corner conversation with the rest of the Guild present– Banichi had gotten off with a sliced hand (hand to hand with another Guildsman) and Jago with a sore shoulder (falling debris from the explosion), while Cenedi and his men had gotten off entirely unscathedc but all of them had tales to tell. Jegari had been determined to stand and attend his young lord, wobbly as he was from concussion; but Cajeiri had ordered him to sit down and have a cup of sweetened tea; and now the two boys chattered away in lowered voices, with animated gestures from Cajeiri as he told his young attendant all the gruesome details he had missed.

Murini was confirmed dead, of small caliber arms fire, uncommonly small caliber. Bren took a deep swallow of wine and tried not to think about aiming at a man in that oncoming line of attackers, but he would do it again, he knew he would. He was sure Banichi and Jago knew exactly who had done it, and whether they told anyone, he left to their judgment: he needed no deeper personal feuds with either the Kadagidi or the Taisigin Marid.

Lord Caiti was also dead—had been dead when they entered the Haidamar. Lord Rodi was dead, the poison having had its ultimate effect about the time the company holding the Haidamar had reached Malguri by phone. Lady Agilisi had gone home to her lowland residence in Catien, in no high good favor, but alive, and now needed to restore herself to the dowager’s good graces by a thorough house cleaning.

While Lady Drien– Lady Drien had come to Malguri to capitalize on her new relationship with her cousin, to sit, looking a little travelworn, but refreshed. She sat, starched and ramrod straight, awaiting breakfast, and quite proud to be participating in the exchange of experiences and timetables. Staff from Cobesthen had arrived by boat, and would take the lady home after breakfast, by which time, Bren presumed, all of them would be very content to collapse into bed and let breakfast settle. He tried to count when he had last seen a mattress. It seemed a while.

The dowager herself had spoken on the phone to Tabini, shocking event. The dowager was not inclined to use telephones.

And then Cajeiri had gotten on the line and blurted out a wild adventure involving digging through a wall, trying to electrocute the guards (but changing his mind) and then watching a giant robot wreck a housec As usual, with Cajeiri, it was all, all true. Bren figured Tabini would come to appreciate this tendency, as the rest of them did.

Always take Cajeiri’s accounts seriously, that was the way to manage the young rascal. Never assume he wouldn’t, couldn’t, or hadn’t.

Bren found himself with a phone call of his own he had to make, once he got a secure line, one on which he could pose a few plain questions to Jase—questions like: what in hell have you been dropping all over the continent? And why?

He’d shed the gun, the locator, all of that, when he’d had a warm bath—which had nearly put him to sleep—and changed for breakfast. “We knew where you were,” Jago told him, “and we believe that Jase-nandi did.”

Now didn’t that say something of that thing’s capabilities, too?

He recalled how Jago’s voice had come through the com quite clearly all of a sudden, when they were in proximity to that robot, and so had everyone else’s voices, at the end.

Relay station, hell. Juggernaut. A lander that could get up and walk.

That sort of gift from the heavens had stirred hostilities in the East, and led Lord Caiti and Lord Rodi to try to deal with Murini instead of supporting Tabini’s party, almost certainly contributing to everything that had gone on.

And if Murini had been a leader of better qualities, and not as suspicious, and not expecting treachery out of Caiti and most anyone else he dealt with, he might not, in fact, have gotten treachery served to him in the end.

Murini had been preemptively fast on the trigger when he thought he was betrayed: Caiti had been acting suspiciously from the moment Murini, arriving from the airport at Cie, had wanted to see the kidnapped boy—who turned out to be gone, to Caiti’s great distress.

And in that confusion of Caiti’s fear at having lost the boy, and Murini’s suspicion of Caiti’s motives, someone had moved first and shots had broken out—the great disadvantage when Guild met non-Guild security. If any of the participants had been of any better character than they had been, affairs might have gone better for the conspirators than they had gone—but they were not, and things had gone very ill indeed the instant Murini had incorrectly concluded he was in a trap. Caiti had reacted, so Ilisidi had gotten from Rodi before he died, by actually attempting to assassinate Murini on the spot. But his guards had been in no wise up to the deed, since half of them had been out desperately chasing Cajeiri.

So Caiti had died, the staff had all fled or died as Murini’s people had gathered from Lord Rodi that the boy really had been there and escaped. They had clear tracks to follow—those of Caiti’s men tracking the boy—so Murini had taken out in pursuit, intending to find the boy and link up with their bus on the road—an airport bus from Cie, as they had guessed, a vehicle which was now in pieces, thanks to Banichi. Lord Rodi, realizing he was left behind in a considerable embarrassment, and faced with explaining either to Murini or to Ilisidi, had swallowed poison which had turned out to be a miscalculation: Ilisidi had been quite willing to let him live. So he died with that knowledge.

And on one other point Murini’s intelligence had badly failed him: he had not been informed the Cadienein-ori runway was still blocked and that Guild out of Shejidan had by then taken control of it—a force now modestly and quietly withdrawing now that the heir was safe, a force vanishing back into the woodwork and pretending it had never, oh, never operated in the East. So Murini would have been trapped there– and been trapped with Cajeiri for a hostage, right in the middle of a firefight.

This had not, of course, happened.

So Murini was confirmed dead, along with most of his Guild bodyguard, two staffers from the Haidamar had gotten back alive, of the five who had gone in pursuit, and it looked very much as if the northernmost district on the lake was now up for inheritance, regardless of whoever Caiti’s heir might be down in the plains. Bren had not tracked the heredity of the Eastern lords as precisely as he knew those of the west. He thought Caiti’s likely beneficiary was a third cousin, and there was a niece, in the case of Lord Rodi.

But the question was very much whether Malguri was going to allow the summer residence in the Haidamar, which it might consider strategic and of interest, to be inherited along with the Saibai’tet—Caiti’s main holding, down in the lowlands, neighboring Agilisi and Rodi. It might claim the Haidamar, if the dowager was in a mood, and she was, and the lowlanders might whistle for their rights to it.

One could grow quite dizzy trying to map the associations and bloodfeuds involved, or that might become involved. But Cajeiri was safe and the two boys were, perhaps a little too noisily, sharing their respective adventures with the Malguri servantsc And thank God for one more thing, Bren said to himself. Toby had left Barb at his coastal estate—to keep up the boat. She would assuredly make demands of the servants. She would naturally botch up the few words of Ragi she might figure out and that would certainly amuse the staff there—at least, one hoped she would amuse them, and do nothing outrageous or insulting. He rather hoped she would stay on the boat, and not accept the natural and courteous invitation to move into the house. God, she would leap at the chance to be lady of the manor.

His eyes drifted shut. Just for a moment. His whole world being in tolerably good order for a change, he decided he could just rest for a moment. No one would notice if he rested scratchy eyes.

He realized then that someone was shaking his arm. He looked up, blinked, to find the whole company on their feet and generally trending toward the dining hall. On one side of him, Toby was leaning on his chair back. On the other, Jago loomed above him, a shadow against Malguri’s yellow lamplight.

A shadow with a sober smile, who at the moment had a hand on his arm.

“Nand’ paidhi,” she said. “Hold out just one more hour, Bren-ji.

Then we can all rest.”