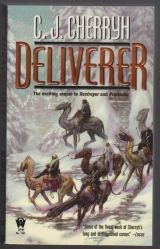

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“This is nand’ Cajeiri, the aiji’s son,” Bren said, fulfilling clear expectations of some sort of ceremony at this arrival. “He has come to felicitate the staff on its survival and is somewhat fond of pizza.”

Faces lit in relief and gentle laughter. There were bows all around, and with the instincts of a consummate politician Cajeiri happily bowed back and beamed. Banichi and Jago stood in close attendance. The Taibeni youths had come in, and stood shyly by, looking entirely uneasy.

“Indeed,” Cajeiri said in his high, childish voice, and in the children’s language. “We are very pleased. Thank you, nadiin.”

This pleased everyone. Smiles broke out, and the staff—the office was already well-stocked with stationery and other supplies—came to beg a ribbon and card for the office, that genteel custom of seals and signatures as mementos of an official contactc “Which we would frame behind glass for the office, nandi.”

“I have no ring,” Cajeiri said sotto voce and still in the children’s language.

“One may just sign and use the office seal,” Bren said. “It will be perfectly adequate for the purpose, young sir.”

“Nandi,” Cajeiri said with a nice little bow, and the staff happily scurried about getting the wax and cards and ribbon– there was even available the black-and-red ribbon of the Ragi atevi as well as the white of the paidhi: the office, dealing as much as it did with protocols, had prepared for all ceremonial eventualities. There was a coil of red wax, there were embossed cards, and Bren, on inspiration, ordered out not just a simple card, but a large sheet of paper vellum for the signatures and seals of everyone who had come in. He signed it himself, and Cajeiri did, as well as signing personal cards. The office had lost most of its framed commemorative cards in the organized vandalism that had hit the former premises, except those that had returned with returning staffers, and now the office had a new start on suitable items to hang, an honor for the place and the moment that cheered everyone.

In the midst of it all, a Messengers’ Guildsman showed up at the door, officially to report Mogari-nai’s dish was indeed functioning and the link was indisputably up. The paidhi could speak to the ship above at his leisure and at this very moment.

“We are very grateful, nadi,” Bren said, and nothing would do, in his staff’s opinion, but immediately to link up a phone, hush the tumultuous party, and indeed, to formally salute the station staff aloft, the entity with whom the office had been in frequent communication, in the name of the paidhi, before the troubles came on them. There was quick consultation on felicitous wording of the formal statement.

The Guildsman, personally put on the spot, saw to the link, and set everything on speaker, so that the whole hushed room could hear the staff at Mogari-nai, out on the coast, actually complete the link to the space station.

“This is Alpha Station,” the human voice came back. “Is this Mogari-nai?”

The office director leaned close to the mike, and said, in passable Mosphei’. “This is the office of the paidhi-aiji in Shejidan, rejoicing to resume communications with the office of the station-aijiin.

Stand by, Alpha Station, for the paidhi.”

Cheers broke out, as the acknowledgment came back, and fell away to an excited hush, as Bren moved close to the mike.

“This is Bren Cameron,” Bren said, leaning near. “Alpha, hello.”

“Bren,” another voice said delightedly.

A smile broke out on Bren’s face when he heard that: he couldn’t help it.

“How are you?” that voice asked him.

“Jase.” He lapsed unthinkingly into ship-manners, then bounced back to Ragi, which Jase understood. “One hardly expected one of the ship-aijiin to be standing by, nandi.”

“This is my watch,” the voice came back with some minuscule delay. “They warned us the link was going up, that they were going to contact you. They’ve been stuttering off and on all this watch. So how are you? Are you safe? Is everyone safe?”

Bren switched to ship-speak, for confirmation. “I’m in the middle of an office party, at the moment, celebrating getting our records back—which we’re doing. We’re putting things back together as fast as we can. The aiji is back in office, the bad guys are on the run, the trains are almost on schedule, and the airlines are back in the air. How are you, up there?”

“May we talk to him?” Cajeiri asked, leaning close, and yelled: “Hi, Jase! Hello!”

“Hello,” the informal reply came back, startled. “Nand’ Cajeiri?”

The boy was on his own agenda. Bren edged Cajeiri back a little.

“You can see,” he said, preempting the mike, “that we’re in good shape here, hale and well. How are your supplies holding out up there?”

“Oh, we’re surviving, but we’re getting damned tired of fishcakes.

We’re in contact with the island. They’re prepping the shuttle there.

They’re telling us the other ships survived. Is that true?”

“Survived, but need extensive maintenance and checks, and likewise training time for the crews—they’re coming in, and unfortunately the simulators didn’t fare as well as the shuttles themselves. A few personnel are taking stock, going through checklists right now, and we can get flight programs and such from the island, even use their sims, I’m sure, if we have to. We don’t have an initial flight date. It may be a couple of months yet, but we will fly.”

“That’s great news,” the answer came down. “Really great news.

We wish it were tomorrow, but that those shuttles survived, that’s a real bonus.”

“How is Gene?” the youthful voice shouted past his shoulder.

“I’m sure he’s well,” Jase answered him. “No great problems in the population. We’re well fed, well housed, and settling in.”

The ship crew settling into the station was probably at about the same state of organization as they were, settling into the Bu-javid, Bren thought, living out of baggage and trying to find their records.

Thousands of refugees from the far station had to be fitted into quarters, and a handful of malcontents had to be put into very secure confinement. The station had already been short of supplies when its population had doubled—with, thank goodness, spare supplies from the ship itself—and order and supply was probably balanced on a knife’s edge now, until the shuttles started making their regular flights.

“We’re going to get essentials up there on a priority,” Bren promised him. “Start making your shopping list. Get that to my staff here as well as over to Shawn. We’ll compare notes and get the number one shuttle going with a full load of the most critical.”

“Wonderful news,” Jase said. “Don’t worry about us starving. The tanks will keep us going, and we’re careful with water, but we’re not short. We’re tracking a near-Earth iceball we’re pretty sure we can nab, give or take a month, and that will set us up much better, in that regard.”

“Good, good,” Bren said.

“We’ll set up a contact schedule,” Jase said. “There are some technicals we need to advise the aiji about. Measures the station took while we were gone, some satellites we deployed during the difficulty.”

Well, that might explain certain complaints. “We have reports of landings.”

“Unmanned ground stations,” Jase said. “Those are separate. I gave your staff a parting gift. Rely on them.”

Bren shot a look at Banichi and Jago, who stood near each other, not far away, their faces completely uninformative– So maybe it wasn’t something to discuss even with this entirely loyal staff, and in front of a trio of youngsters who weren’t a fraction that discreet.

“I’ll ask, then,” he said, taken aback—as he was sure Banichi and Jago were, since that had been one of the ongoing puzzles of the new administration. “It’s good to hear your voice, friend.”

“I’ve been worried about you,” Jase said.

“Mutual.” So Jase was safe. There had been no riot among the four-thousand-odd stationers they had just installed in a station with limited food and water. But with Jase reporting in safe and secure, his other personal worry, Toby, came back to him with particular force in the moment. He didn’t intersperse personal crises with official ones, not if he could help it, but Toby had deserved official attention, dammit, some gratitude for his part in things—and communication was still newly restored: his present recourse to the ship and the island might be more than spotty in days to come. “Jase, you haven’t heard anything from my brother Toby, have you?”

A pause. “I know his location.”

My God. He was ordinarily cautious. He’d tumbled into this one in front of a room of witnesses, the way he’d just done about the unauthorized landings. He blurted out, nonethless: “Is he safe?”

“Tyers knows. Can you ask him?”

Shawn Tyers. The President. He’d asked Shawn to find out. And Shawn had been in contact with the ship. He was numb with shock and—he thought—relief. And there was the Messenger standing by, who might or might not penetrate deep ship-speak slang. He had just blown cover. Not badly, but enough to say Toby was in play, and Shawn knew.

“Is he all right?”

“He’s safe.”

So Toby was listening, he thought. Still on duty. His heart was pounding. The wretch hadn’t just done one mission for the government: he’d posted himself offshore to relay information. And now that he’d just blown his cover, Toby had urgently to be reeled in. “Thank you, Jase. Thanks.”

“I’d better let you go,” Jase said, “and go report. We’re at shift-change. Sabin and Ogun will want me to say hello on their behalf.”

“Hello back.”

“Can you say hello to Gene for me?” Cajeiri asked, bouncing into mike range.

“I shall, young sir.” The last came in Ragi, and Cajeiri– there was no restraining him—looked at least mollified.

“Please let him call me, Jase-aiji!” Cajeiri cried.

“Thank you, Jase-ji,” Bren said.

“Take care,” Jase said, without answering the juvenile request, and the contact went out. The room broke into cheers, after its breathless silence, staffers delighted to have another demonstration that essential systems were working, and the Messenger looked absolutely relieved that it had gone without glitch—in itself, encouragement to believe this was an honest man—though one could not but think this was the one mission in all the continent that the chancier leadership of that Guild would want in the hands of a man of their own. He didn’t trust him. Not for a gold-plated instant.

“Your leave, nandi,” that man said, bowing. “I shall report the contact a success.”

“With my gratitude,” Bren said. “With utmost gratitude to your Guild. Wait.” They had all the appurtenances of ceremony, and wax was still ready. He signed and sealed cards for the occasion, one for the Messenger and one for the Messengers’ Guild as a whole, before the Messenger left their company, an official sentiment of thanks and a memento of the occasion. The network was back up, communications were restored with the space station and the ship, and most of all with Captain Jase Graham, who had just told him what Toby was up to—and he could just about guess where Toby was– —keeping absolute silence and quiet in a zone Bren particularly knew, a little triangle where there was no regular shipping, where fishermen generally didn’t venture, it being inconveniently far from various villages—and where Toby might even have been somewhat in intermittent touch with his own estate staff. His estate had supplied themselves during the troubles by fishing those waters.

The Messenger left, an honest man or not, he had no way to know, maybe quite smug in having been respectfully received, and bearing his report. It was a damned mess.

And the phone lines were still down and the radio was a security risk; and if he told Toby to get into port at his estate, now, today, and lie low, he would have told the whole Assassins’ Guild Toby was out there, which could mean a race or an ambush. He was a fool—he had been elated, and off balance, and Jase had tried to warn him off, hadn’t he? It was Jase who’d used common sense, not he.

Meanwhile Cajeiri stood there, eye to eye with him, looking both defiant and hopeful. “One would wish, Bren-nandi, to call Gene on the radio.”

Cajeiri, among other distractions, had not behaved well, had not behaved well in public, what was more, and now compounded matters by his behavior. It was not for the paidhi-aiji to discipline the aiji’s heir, and Cajeiri knew that, too, knew it damned well, and pushed—hard.

Bren stared him straight in the eye and said, on the edge of his own temper, “Ask your father for such permission, young sir.”

“You know what my father says.” The latter was in Mosphei’. By now, clearly, the whole room knew the heir was fluent in that forbidden language, a matter the aiji had somewhat hoped to have less public. There lingered a stunned and uncertain silence in the merrymaking.

“I do know the aiji’s opinion, as happens,” Bren said, keenly aware, as the heir himself seemed to have minimum regard of the witnesses. “I also know that words on the wind do not come back.”

Cajeiri’s chin lifted slightly. That had been a quote from his great-grandmother’s repertoire; and the boy surely recognized the reprimand.

“These are, of course, the paidhi’s loyal staff,” Bren said in ship-speak, “and loyal to your father and to you as well. One asks consideration for them in that regard, young sir. Because they are loyal, their restraint and their secret-keeping should not be abused.

Nor can any of us vouch for the Messenger, who just left.”

Did just a hint of embarrassment touch that prideful young countenance?

It might be. It was a reprimand as graciously delivered as the paidhi could manage, and the paidhi did not ask the respective bodyguards to manage the situation, nor dismiss the party, nor lodge a complaint with house security, or ask for the arrest and detention of what might be an honest man of a troublesome Guild.

Cajeiri could figure, by now, that he had been rude, and excessive, and beyond indiscreet. In an atevi way, Cajeiri was privately adding the numbers of the situation. He certainly had gone blank-faced.

“Indeed,” Cajeiri said, that immemorial refuge of atevi caught short of words. He gave a slight bow, sober and restrained. “We thank you for the hospitality, nand’ paidhi, and felicitate you on the occasion.”

The memorized phrases, the precisely memorized phrases: Cajeiri had been able to lisp that formula, more than likely, when he was five.

“One owes an apology, nand’ paidhi,” Cajeiri added then, the courtesy his great-grandmother had thumped into his skull. It seemed sincere. Certainly it was public.

And it just could not pass without comment. “Young sir,” Bren said, as severely as he had ever spoken to the boy, “speak to me later.”

“When shall I, ever?” A little uneasy conversation had resumed in the room, staff attempting to resume the party, but everyone went silent a second time at that sharp young voice. Even Cajeiri seemed taken aback by the resulting silence.

So. And was that “when shall I?” the source of the misbehavior?

Resentment for desertion, a wicked, childish prank suddenly spiraling into the spite and full-blown anger of a young lord?

“By my will,” Bren said in measured tones, “certainly you may call me whenever you will, young gentleman, and whenever your father allows. I have missed you very much.”

Cajeiri had his mouth open for some other tart remark. He shut it, looking as if he had just been hit in the stomach.

“Nandi,” Cajeiri said then, and bowed, and left the office, drawing his two mortified Taibeni companions with him.

He had not suggested the young rascal visit him. He had challenged the boy to summon him through his father’s front door—which was exactly the situation: thorny, difficult, and not the paidhi’s to mend. Cajeiri might just have figured it out.

Oh, doubtless there would be storms once Cajeiri reached the privacy of his father’s apartment. Bren felt, rather than saw, Banichi’s close presence, and Jago’s, supporting him.

But there was more than one crisis going on. He tried to regroup, knew he urgently needed to do something about the situation he had just put Toby in, being an utter fool—since hostile clans knew the shipping lanes just as well as the rest of them. In the subsurface of his mind, he wished he had dealt otherwise with the young heir, maybe drawing the boy out into the hall to have that last exchange with him. It had been, God help him, public. In front of the whole staff. Yes, he had tried to get Cajeiri to deal in private, and yes, Cajeiri had kept after him—but was he, like Cajeiri, eight-years-old? He had been psychologically pressed, dealing with someone at eye level, but it was an eight year old boy, for God’s sake. What else was Cajeiri going to do but throw all his ammunition? And now he had gotten rattled enough to breach security, risking his own brother’s life. And he had put his staff in a position, besidesc Besides this deliberately provocative turn in the boy, who was no saint, nor had been on the ship. But there Cajeiri had kept to pranks, not such deliberate misdeed. He was no longer in any authority over the boy, and the boy was acting out with a vengeance. It was not a pretty character trait the whole office had just seen, and it was not private: it had public implications, in the fitness of the aiji’s heir and the dowager’s teaching, and he himself had not come off with any credit in the business.

“We have to reach Toby,” he said under his breath to Banichi and Jago, looking all the while at his office staff, who still stood thunderstruck, caught between pretending they hadn’t heard and the respect they tried to pay to his distress and embarrassment.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said then, and gave a sober little bow. What did he ask them? For discretion on a private matter? His own staff were devoted to him, and it would insult their man’chi to imply they would talk. Did he plead that he had lost his focus and that the boy was having a tantrum? Both were evident enough. “Thank you very much. The message contained excellent personal news. My brother is found safe, and his location must be kept secret. One has every confidence in this company.”

There were bows. One could have heard the proverbial pin drop.

Acknowledge that the heir had been a brat?

There were some things atevi did not mention. Children were one of those topics, a private matter, intensely so.

“Please,” he said, with a broad gesture, “this is a celebration, and with every reason to celebrate. Continue, please, nadiin-ji. And thank you.”

The room collectively drew a breath. People moved from where they had rooted themselves, and refilled cups and opened pizza boxes.

He refilled his own cup, trying to seem casual, wishing it were stronger, and turned from the watchers to Banichi and Jago.

“I should have applied the brake on the young gentleman at the very first,” he said under his breath. “One entirely misread him, nadiin-ji.”

“He realized he was in the wrong,” Jago said.

“The witnesses have children of their own,” Banichi said. “Even his father has had to restrain that one in public. And we have just contacted Tano, nandi. We will find nand’ Toby. We are moving on the matter.”

That was a vast comfort on that front. On the other– “What we lack is the dowager’s stick,” he said shakily, and drew grins from both of them, which afforded the large room encouragement to more noise. The air in the room lightened perceptibly.

“He goes about the halls with only the Taibeni,” Banichi said under his breath. “Which is not good, nandi. One has no idea how he has shaken his guards.”

“They told me they were at the library,” Bren said. “He has abused a parental permission, one suspects.”

“He has deceived his father’s staff,” Jago said. “This is not a small matter, Bren-ji. His security needs to know exactly what he has done, and report it to the aiji.”

“Indeed,” he said, and was not surprised when Banichi named himself to go, and likewise to consult with Tano on the other matter. “Do, nadi-ji,” he said, and Banichi left on that dual mission.

“We no longer live on the ship, nandi,” Jago said.

“No, we do not,” he said, aware they were still under furtive observation by the staffc and being aware, he turned from Jago and picked his individual, his advisor in correspondence protocols, an old man many times a grandfather. Idly wandering over into converse with the old man, he remarked, “The heir misses his great-grandmother, misses my staff. Hearing of a party, the boy hoped, one believes, for a few guests here his own age.”

He did not mention that the heir of the aishidi’tat had formed strong associational bonds to a human, never mind he had quite publicly and vehemently attempted to contact a human aboard the ship, disregarding all protocols with a ship-aiji in the process. And never mind he had never heard of an adult party with children in attendance. It was a foolish excuse he had uttered. His mind still racketed back and forth between the mainland and the ship aloft.

Here and there. Now and then.

So, unfortunately, must Cajeiri’s. The boy was eight. How was he to know what the world’s customs were, regarding parties?

“One entirely understands, nand’ paidhi,” the old man said in low tones. “A nameless year, a difficult age. And the boy has been right in the thick of the trouble. He doubtless has assumed a certain maturity of expectations.”

That was certainly one way to put it.

“He accompanied us,” he agreed, “through gunfire, explosions, shellingc all directed near him. At a certain point, we had to restrain him from rushing to our rescue.”

The old man laughed gently, perhaps taking it all for exaggeration. It was not.

“A bright and excellent young man,” the old man agreed. “The aishidi’tat will be well led, in his day.”

He had several virtues, did the protocol officer. He was dignified, he expressed himself well, and he was very willing to spread his tidbit of information at least among staff. As diplomacy went, it was a little like painting, starting with the black and the white of a situation, adding a little color here and there, until the disastrous image revised itself.

He only wished his gaffe with Toby’s situation could be so readily patched. He imagined hostile Assasssins moving at high speed, seeking to reach those waters.

On the sea, however, he would wager on Toby’s side: Toby handled that boat with great expertise, and would let no one near him that looked in the least suspicious.

“Banichi has overtaken them, and has them under personal escort, nandi,” Jago said, meaning the boys. “He will speak to Casimi and Seimaji.”

Those were the boy’s proper, adult, and Guild security—the ones the young rascal had escaped. The discomfiture of Guild members was profound, even life-threatening. The Assassins’ Guild did not accept excuses.

“I shall owe my own explanation to the aiji,” Bren replied, not looking forward to that, either.

Jago looked no happier in that prospect than he was. But, he said to himself, thank God Toby was accounted for—damn him. Toby couldn’t let it go, couldn’t just go back to port—he’d probably already had his understanding with Shawn Tyers, no less, the President of Mospheira, that day that he’d showed up at the hotel, and he hadn’t gone back to the island after landing his errant brother and his party on the coast, no, he’d simply sailed south to waters he knew would be close to information, trusting no one with his position, and hanging about the coast, ready even to intervene, it might be, if things had gone badly in their return to the continent—relaying news reports while he sat there, and ready for a pickup.

And Toby wouldn’t know now that his brother had just made him a target. Maybe at this point they just ought to use the radio, blast out a warning to Toby to get out of those waters, now—it would set the hunters on his track, no question, but Toby with that advance warning could elude most threats.

Except it wasn’t some random lunatic with a cranky motor-boat they had to worry about. What might go out would be much better equipped, much faster.

Near his estate; he had his own boat. If he could get out to the coast on a private flight, pretending an oddly-timed vacation, he could be there in two hours, could sail out and personally tell Toby to go homec No. His going to the coast would draw every assassin in the region precisely in that direction. And Banichi had already talked to Tano—had alerted him to something, and would probably meet him with plans the moment he had delivered the boy to his father’s door upstairs. Something would be done, something far more efficient than he could manage.

God, he had to keep his mind on present business. The secretary in front of him had presented him a complex proposal about the priorities for answering secondary correspondence, and he had only half heard it. “Indeed,” he said, foreseeing no possible damage from the order he had just half-heard, and, rattled as he was, he was willing to be obliging to his patient staff. “That seems a good idea, nadi.”

There was just too much coming at him. He had lived aboard the ship in a stultifyingly quiet routine, and now every unattended piece of his life seemed to have come loose and careened out of control. He had heard from Jase, who desperately needed him to get the shuttles flying, and meanwhile the station had launched equipment toward the planet without advising him, or, possibly, without advising the legitimate aiji—possibly aimed at Murini, but violating several treaties in the process. Toby was found, doing something entirely logical, but out of reach and unaware his brother had been an oblivious fool. Cajeiri had run amok, and the aiji and the dowager were going to get that report before sunset. He wanted to seize every stray piece of his life, set it firmly in separate chairs, and keep everything still until his brain caught up to speed, but he foresaw that was not likely to happen.

What in hell was the matter with him? Cajeiri had blown up under his care, and he had lost his focus entirely. Surrounded by computers, he had outright forgotten he wasn’t on the ship, in that limited environment, with limited enemies. So, perhaps, had the boy. And that had fixed the rest. That just could not happen twice.

He drew a deep breath, tried to center his thoughts on a staff resuming their good time, and wished for the second time he dared take a cup of something rather stronger than tea.

6

“Toby, Jago-ji,” Bren said, broaching the topic again the moment they were done with the festivities, out the door, and on the way back to his own apartment: “What are we doing?”

“Banichi will have moved on it, Bren-ji,” Jago said. “He has not informed me of the details, but he is on his way back to the apartment.”

The Guild used verbal code on their private communications. One could wonder what the day’s code was for “the paidhi has been a complete fool,” or “do not trust him until he has recovered his good sense,” but Jago walked along with him at deliberate speed, took the public lift with him, and so up to the main level where they took the restricted lift homeward, into the elegantly carpeted hallway with the tables, the priceless porcelain vases, the portraits, and the seasonal flowers. It was a place restored to kabiu and tranquillity. It soothed, it advised, it warned.

They passed the aiji’s temporary residence, where the aiji’s guards stood. They went on to their own quarters, on the opposite side of the hall and down some distance, where the only one on guard was Banichi, a looming shadow by the door.

They entered the apartment together, and Bren surrendered his formal coat to Madam Saidin, who took one look at their faces and asked no immediate questions. Her staff provided him the less formal house coat, and immediately, at her signal, left them in discreet silence.

Even so, he waited until they had reached the study and shut the doors.

“One is extremely distressed,” Bren said, “to have been an utter fool, Banichi-ji. The Messenger’s presence—”

“That man has passed clearances to deal with the aiji’s messages,” Banichi said. “But we take nothing for granted, Bren-ji.

Your boat is awaiting orders. Tano and Algini are already at the airport. Our immediate plan is for them to go out and bring nand’ Toby in to your estate quietly if at all possible, and not have him exposed in the long crossing.”

He drew an easier breath. “Nadiin-ji, words cannot express—”

“Tano and Algini will use the young aiji’s fish for a code word.”

That lethal catch of Cajeiri’s, that had flown all about the vicinity on a wildly swaying line. Only someone who had been on that deck would know that reference.

“Excellent.” Tano and Algini could function in Mosphei’, at least, and he hoped fish was among the words they knew: Toby’s grasp of Ragi was limited. But he was immensely relieved, all the same.

“We updated the estate staff’s codes four days ago,” Jago said very quietly.

And they could communicate with less prospect of having their code cracked. Such efficiency was like them. He could only wish he had matched their precautions.

Soft-headedness. Too much reliance on staff to think of things. A steel environment that simply didn’t change, while the universe ripped past at mind-blurring speed.

“One is immensely grateful,” he said. “Well covered, nadiin-ji.

Well covered.”

Jago quietly poured a brandy at the sideboard and offered it to him.

He took it. His lapse had taken his innermost staff down to two, again, and settled work on their shoulders. He owed it to them to sit down and accept that they had things in hand.

“Sit with me,” he asked them, “if I have given you the leisure to do so, nadiin-ji.”

They settled, Banichi with an unreadable expression—one had the faintest notion it was tolerant amusement.

“Brandy if you wish,” he said.

“We remain on duty, Bren-ji,” Jago said.

“And I have immensely complicated your problems,” he said. “You know where he is.”

“With reasonable accuracy, given Jase-aiji’s information,” Banichi said. “But well that we do know, and well that we move quickly.