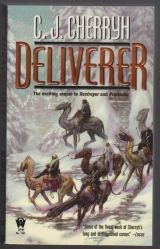

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Well,” his mother said, reaching out for his hand. He gave it, and she straightened his already straight cuff—he was absolutely certain it was straight—and patted his hand as if he were a toddler.

“What occasions this finery, son of mine?”

His mother very well knew he had just gotten caught in the halls. He was absolutely certain of it, and his father sipped his tea, not quite looking at him. His planned approach began to fall apart, if his father was going to let his mother deal with him, and particularly if he was due for a punishment.

“One greatly regrets, honored Mother—” It was Great-grandmother’s best manners, her most precise formalities.

“One regrets a breach of propriety, Mother-mine. And honored Father.” Another bow, difficult with his hand imprisoned, and he looked the while at his father, trying to judge his reaction. “One had come to pay respects to nand’ Bren in his office, and when nand’ Bren reached the ship by radio—it was exciting. Everyone was excited, and one very regrettably made a misjudgment, a great misjudgment. Nand’ Bren will not complain, but it was a great embarrassment.”

“What precisely did you do?” his father asked, looking straight at him, and gave a hint of that expression that terrified councillors.

But he was ready for it: he had assumed his most sober face.

“One interrupted the paidhi-aiji, honored Father, when he was speaking to Jase-aiji: I spoke to Jase-aiji myself. I know him very well, honored Father. It hardly seemed rude at the moment. It was, however, a great misjudgment.”

“And what was the nature of this address?”

“I sent a small courtesy to my associates, to say that I am safe and well. They must be worried.”

“Indeed.” His father’s indeed could wither grass. “And a ship-aiji was to deliver this message in person?”

“Jase-aiji knows me very well, honored Father, and may well do it very quickly, by computer. And one was in all courtesy required to assure my associates of my safety. If I could send a letter up—”

“The welfare of the station and the ship are dependent on the slender resources of Mogari-nai, and my son wishes to send letters.”

“But the transmission of letters is very fast, honored Father. A whole library could go right in the middle of someone talking, and the computers would never even slow down at all. I used to write every day, everyone does it, on the ship—letters go back and forth all the time, sometimes just a word or two.”

His father lifted both brows. “In which language, son of mine?”

Caught. “In Mosphei’, honored Father.” And he was determined not to look guilty. “You surely know Mosphei’. It seems useful to know.”

His father’s expression changed not at all. “And you are in the habit of sending such personal letters?”

“Everyone does, honored Father! The system has all sorts of traffic. Even the lights going on and off are on the system. It just goes so fast no one notices. Computers are like that. Jase-aiji knows it would be no disturbance at all for me to send letters– if we could write back and forth, it would make me ever so happy, and I could find out things that go on in the station– that would be useful to you, would it not? And the computers would never slow down at all, never. The ship-folk send hundreds and hundreds of letters all day long, even silly one word letters, and the computers never blink—the lights go on and off and the air moves and everything runs without a mistake, all while thousands of letters go back and forth in every watch and everybody talks at once—just as if everyone were sitting in one room. And if one is asleep and not able to receive a message, it sits and waits for notice.”

“This seems quite a wonder,” his mother remarked into the silence that followed.

“We could have such a thing here, honored Mother! We could set it up if we had only a few computers. And it runs so fast! If I had had the system with me in Tirnamardi—”

“Uncle Tatiseigi would have had a seizure,” his father remarked.

“But if I had had it, honored Father, we would have been able to send letters as fast as a phone call. Just like that, only to hundreds and thousands of people at once. And we could have gathered even more people!”

“A few computers,” his father echoed, so far back in his train of thought that he had to blink to remember what he had said.

“Well, and one needs the connections between them, honored Father. But it takes hardly anything at all to run it, no extra power, and computers run so fast they always have time for letters or even whole conversations—they hardly notice at all while they do other jobs.”

“Indeed,” his father said, but this time it was not the withering version. In fact, his father had leaned a little his direction, and his eyes sparked with a faint interest. “One imagines the ship system my son used must be much more advanced than we have here.”

“But we could do it here, honored Father! We could connect up the mail and the phones and the security systems and the servants and everything just like theirs, and once you have the computers talking to each other, it goes far faster than phones, because if you call someone, you have to say hello and they have to say hello and you have to talk through the courtesies, but these are just pieces of information, just sitting there waiting for you, just the things you need to know. And they fly from computer to computer as fast as thinking. Mani-ma said there was a rudeness about it, but if one’s staff does it, then the servants can throw out the silly bits and find the important things. Mani’s staff did, and her staff sent back and forth to Lord Bren’s all the time. The Guild does it. One is very certain the Assassins’ Guild does it.”

“Interesting.”

It was close, so close. He had his father’s attention. He plunged ahead. “If I could get Gene to get the manuals—he could just send them down to me by Mogari-nai, and once we had the manuals, we could set it up with just two or three computers, and then we would hardly need the—Messengers’ Guild.”

“One is certain the Messengers’ Guild would be gratified to think so.”

“But, well, they could find something to do. They can run computers.”

“Gene is this young associate of yours on the ship.”

“He is extremely reliable, honored Father.”

“And he will somehow find the ship’s manuals and give them to us without the paidhi’s intercession? Remarkable, this reliability.”

“Everybody has the manuals, honored Father, well, the ordinary onesc One can even use the computers to read their own manuals.”

“And you can read them that fluently?” He was caught with his mouth open. He shut it, and bowed. “Yes, honored Father. I can.”

“And in which language does my son habitually speak with Gene?”

Deeper and deeper. And a lie would come out to his discredit, at the worst possible time. “Whichever one seems to fit, honored father.”

“Ah,” his mother said. “So Gene speaks Ragi.”

“A little. Just a little of the children’s language.”

“And you,” his father said, “speak the ship-language and Mosphei’ and this alien language, too.”

He bowed respectfully. “Yes, honored Father. Expediency.”

“Expediency. What a precocious choice of words.”

“Mani would say that. But she taught me, honored Father.”

“Well, well, two years in her care, and one is hardly surprised at such thoughts.”

“I ever so need to maintain these associations with the ship-folk, honored Father. You have nand’ Bren, and his advice. I have Gene.”

“A person untested and unadvised.”

“He will grow up, honored Mother. And so will I!”

“And you wish to slip a personal letter through this wonderful system,” his father said, “of course with a ship-aiji’s permission, asking that technical information be sent down—with or without the paidhi’s intercession?”

“It would be absolutely no inconvenience to the system, honored Father. And nand’ Bren would approve. And it is honorably owed that I present courtesies to Gene-nadi. I had no proper chance even to speak to them when I left.”

“Them,” his father said. It was a question.

“Gene, and Artur, and Irene, and Bjorn.”

“The convenient number of a personal guard.”

“They were that. They were, honored Father. They would defend me.”

“They are children,” his mother said.

But his father gave a small wave of his hand, which he dared hope was indulgent dismissal, with permission. “Compose a letter.

Nand’ Bren must approve it before sending. You will not ask for the theft of manuals. You may ask nand’ Bren what he will request for you, in that line, and what nand’ Bren approves may go out. Only what he approves may go. Is that clear? He is the paidhi, and he must rule on technological matters, even when we see ways around his authority. You will need his favor, and he will need my permission as we need his assent to obtain such books. That is the way the world turns. See to it.”

“Shall we have computers, if one can get the manuals, honored Father?”

“Ask Bren-paidhi, I say! Deal with him!”

Did his father already know how angry Lord Bren was with him, and that he had somewhat skirted the truth in that matter? It was possible. It was also possible that particular complaint was still to blow up as badly as it might. It was probably not the time to ask for a television.

“Honored Father.” He bowed. “Honored Mother.”

“You will not leave these premises without senior security,” his father said. “Deal with Lord Bren as best you can.”

“Yes, honored Father.” Another bow. One to his mother. And a retreat without argument. He had learned that with Great-grandmother: if one had gained something in the exchange, it was not time to risk losing more than one had come in with.

He exited with his tidbit of permission and walked, head high, back to his own rooms, collecting his two implacable Atageini guards and Great-grandmother’s two men, and Antaro and Jegari fell in as he went. Antaro and Jegari he bade come inside, and left the other guards standing at the door, if that was where they were determined to stand, in a household guarded by his father’s men, and all sorts of other precautions. He was what they were watching, not protecting his personal premises from intrusion. If there was intrusion, they were likely the ones committing it—which was the unfortunate difference between here and the ship.

Antaro and Jegari were too polite to ask what had just happened or how the interview with his father had affected their fortunes. So he told them. “I have permission to write a letter to the station. The misfortune is that those two outside have to go with us everywhere, nadiin-ji.” He was bitterly upset and tried not to let it affect his voice or his manner. “They are upset with us and now my father has said they have to be with us. So they will go with us to the library. I think my father has heard another story of where we went today.”

Their faces were duly sympathetic. “These guards outside our door are men who are in your great-uncle’s man’chi, nandi. They do not favor Taibeni.”

“They do not,” he agreed glumly, thinking that if he were clever he might still get out the door alone, but he had better make it worth it. In an otherwise idle portion of his mind, he wondered how Great-grandmother would deal with the situation if he and his staff simply went down to the public train and showed up at the Atageini station.

More to the point, he had to wonder how his father would deal with such a slippery move, and he did not think the outcome would be good.

Tano and Algini were on the next air cargo flight to the coast—Jago was in touch with them, and she would, Bren was sure, tell him if there was any glitch in their plan. Tano and Algini would reach the coast, the local boat would get them to the yacht, and they would go with the party from the household to make absolutely certain they could find Toby out at sea. They had the best of chances. The best of equipment, that was certain.

Bren rested on pins and needles the while.

And in the meanwhile, since a note had arrived from the aiji, he was already scheduled for a special meeting with Tabini before supper—God, there went the schedule. The note did not give the reasons of such a summons, and that meant having all his mental resources in working order. The occasion of the office party had at least gotten the staff together, and now the party-goers were at work restoring order in the premises and cleaning up the last of the crumbs, so that was handledc he had meant to go back, but postponed that.

By tomorrow, the office would be in full swing, and he had set its number one priority as getting communications established and bringing the shuttles—in some measure the paidhi’s particular responsibility from the beginning—up to operation as soon as possible. That had become the paidhi’s responsibility in the first place because building the shuttles had meant coordinating an immense volume of cross-cultural communications, and (which had never been the paidhi’s responsibilty, but which had become so) getting the secretive and jealous Guilds and various legislative departments into communication with each other.

And Mogari-nai was talking. The station was talking to departments again—granted the link stayed up. Tabini might want to get straight what the station had to say.

And for his own agenda, the earthbound Pilots’ Guild had to reestablish its training facilities, the technical branch of the Mechanics had to establish its space operations offices and get credentials in order. All of it, what little he had begun to heave into motion, had been on his shoulders until now. Now he had a thousand hands, a hundred small offices in communication with his staff. And it was not at all excessive for the task.

The whole space services system had to be repaired, from manufacturing and testing upwardc and his staff, who had done the bulk of the translations, now had to get those manuals and the people trained in the professions reunited, not to mention printing copies of the manuals and training and checking out any new personnel they had to hire—and then double-checking to be sure what was agreed upon to do had actually got done. Equipment had to be checked, down to the smallest detail, and materials and spare parts had to be found, a great deal of it unique to the shuttles, which meant a supply reserve of less than ten, down to spare bolts and cover plates, if they were lucky. The inventory system had gone into chaos.

There had to be staff lists, at the companies that manufactured the parts. There had to be copies of the agreements and specifications. All, all this complex business meant finding experts scattered to the windsc and being sure they were loyal, which meant, though reluctantly, engagement of the Assassins’ Guild, with its investigative expertise at finding out man’chi, estimating relationships—he doubted there was a single individual inside the program who had wholeheartedly supported Murini, but that confidence did not extend down into, say, the third marriage of the financially troubled factory worker. That depth of understanding was easily the province of the Assassins, who could gather up that sort of information as readily as asking the local membership.

And it all had to be done. They had a station up there depending on resupply of critical things the planet provided, and they had a space program to get running.

But they could not make the same mistakes as they had made in the past, to so trample on certain regional jealousies as to create uproar and protest. There had to be an oversight committee, someone to investigate the validity of complaints and mediate where mediation would serve.

And it was not precisely the paidhi’s job to suggest to Tabini that he hear regional complaints the paidhi saw fit to bring to his office, but he felt constrained to try, if the opportunity presented itself.

Damned sure few other court functionaries had the gall to broach the topic.

With Tabini, there was quite often no round of tea before talk.

One went into the room and delivered information, answered quick questions, heard the aiji’s instructions and bowed one’s way out.

The aiji’s schedule would have the aiji awash in tea if he were not, to a certain degree, abrupt and untraditional.

Today, however, there was tea offered, setting a genteel pace for such a private meeting. And a cup of tea provided time enough to recall the heir’s invasion of the party, the problems he had presented the aiji’s house, and the various reasons the aiji might have for a summons of the paidhi-aiji which did not involve the paidhi’s agenda with the space program, his office, or the location of his missing brother. One waited for the aiji to declare the subject of the meeting. And waited, until the tea ran out.

“My son,” Tabini began ominously, and then took an unexpected curvec “suggests we link computers together, for ease of communication within the household, and one is not certain how much farther. He believes he can do this if he has certain manuals he declares to exist on the ship.”

Bren drew in a breath, thinking rapidly, and finding himself at the edge of a cliff, and not at all the cliff he had planned. “To do that, aiji-ma, yes, he indeed has the skills do it, given computers with the capacity to connect. The aiji knows we do this in a limited fashion. But to establish that link for personal communications the young gentleman envisions, in the fashion the young gentleman has been accustomed to use on the ship—the changes the space program has brought would be slight, compared to the changes such a system would bring, implemented in full. And I must say, in all good will, aiji-ma, the regions are distraught enough—”

“Name these changes.”

“Speed of information would increase. So would proliferation of bad information and rumor. Speed of daily events would increase.

Secrets would travel down paths that would proliferate by the hour and change in retelling. The giving of decorous invitations and messages would meet the same challenges the custom encountered in the introduction of telephones. Communication would become more abrupt. And less formal. I cannot immediately foresee all the changes such a system would bring, but I advise against it, aiji-ma.

Given the upheavals already troubling atevi life, I very much advise against opening that particular door for the young gentleman, no matter his frustrations with the pace of things. The ship operates entirely on linked computers. If one wants something, one does not go to a master of craft; one requests a computer to act, and the computer figuratively opens a book in some library and makes that information available instantly. It can contact another computer and has a message waiting for some associate the moment he sits down to use the machine, much like the message bowl in the foyer.

But it leaves no papers behind. And it is subject to misuse. A skilled operator can reach out and affect a system half the ship away, or gain a key to one he is not supposed to enter. Security becomes a major concern.”

“My son,” Tabini said, and sighed, chin on fist. “My son, one fears, wants to recreate the ship.”

“He will adjust his thinking, aiji-ma. He understands the ship very well, but he is only beginning to meet the world. The aishidi’tat must not see the heir as providing a more rapid pace of change than his father has done.”

Tabini gazed at him a long moment in silence, with that remarkable pale stare. “Perhaps we erred not to keep him here with us. But one does not know how he would have survived, where we have been.”

One could only guess what territory that covered: the aiji’s survival had been a hard struggle, one that had left its mark on Tabini—he was harder, leaner, his eyes darting to small sounds.

And he had grown more reticent, if that was possible.

“What he has learned on the ship, aiji-ma, will benefit atevi all his life—if these things are wisely delivered.”

“Are they true things, paidhi-aiji? Are they truly profitable? Or are they like this computer system, fraught with immeasurable problems? And can the paidhi explain to the child why this should not be undertaken?”

It hit him with peculiar force, that question. No, it was not possible to explain such things to a boy who saw only the ship, and who had not truly met the world such things would disturb. The father might have met the problems inherent in hasty change; the son had yet to know there were problems.

“I shall at least try to explain to him, if the aiji wishes.”

“Perhaps he will listen to you.”

That was equally troubling, such a request from Cajeiri’s fatherc who was accustomed to obedience from strangers. Not to have obedience from his own son– “He will more aptly listen to Banichi, aiji-ma. And Banichi can say things very simply: I think he will say that if the young gentleman does such things it will create a great deal of bother the young gentleman will have to deal with.”

Tabini had not smiled often since his return. This smile began subtly, and became an outright laugh as he sat upright. “The paidhi has a certain insight into my son’s thinking.”

Tabini remained amused, and the slight smile lightened everything. It was a vast relief to find communication opening up, both of them finally seeming on the same wave length about risk and change, and with something like the old easiness coming back to their conversation. Things southward, Bren thought, must be going well—the mop-up of the rebellion was proceeding. And things with the boy must not be all that bad: certain families might be disturbed to know their offspring was somewhat self-centered and not quite thinking of their interests so much as his own ambitions.

But a future aiji was somewhat self-centered.

“Well, well,” Tabini said then, leaning back and seeming to have recovered his sense of humor. “So the dish at Mogari-nai is up. And Jase-aiji speaks to my son in front of your staffc I have had the transcript.” A small wave of his hand dismissed any report on the details. “And Toby-nadi is found. This personal news surely pleases you.”

“Immeasurably so, aiji-ma.” He was so relieved he only then recalled that the whole conversation, ergo the transcript, had been in ship-speak.

“Amazing feat,” Tabini said, “to locate a specific boat, in so much water.”

“Your staff may have told you, aiji-ma—” Straight to the one piece of news he must not seem to conceal—nor had he any such intent. “The ship established much more precise surveillance over the world during the disturbance. It has—I surmise—established numbers for the entire planet, in a gridwork of precise coordinates.

It dropped ground stations—these, I have discovered, are the mysterious landings in the reports: I believe they must be communications relays, but I am far from certain, or whether they are even connected to this mapping system. I am seeking clarification on that point—I am not familiar with the details of the technology, and it was not sent through my office.” And dared he tell the rest, the precise location of persons available with the equipment his staff carried?

A world where hiding became impossible, where, first of all persons, Assassins were in possession of such devices, starting with his own staff? It was another earthquake of information as profound as a computer web, and Jase had blithely handed the technology to his security staff without consulting him.

But then, the station had deployed its mysterious ground-based devices without consulting Murini, eitherc and God knew what they did.

“Aiji-ma, my own staff carries certain items related to that technology, which they were given on the station, and I have only just been apprised of the fact. We rushed from the ship to the shuttle, with very limited time to settle certain matters. I did not approve. I have the greatest misgivings about that technology existing down here.”

“Down here.”

“On the planet, aiji-ma.” So profoundly his view of the universe had been set in the heavens, not on the planet where he was born.

He had to re-center himself in the planet-based universe. He had to make certain other mental adjustments, urgently. “I think it may possibly constitute a very dangerous development—useful to the Pilots’ Guild, but as worrisome in the hands of the Assassins as the computer link in the hands of the public. It will possibly give precise locations of anyone who has such a device on his person. It can inform anyone who carries it precisely where he is, on a map.

Useful—but fraught with possibilities.”

“Interesting,” said the most dangerous schemer the aishidi’tat had ever produced. “Indeed, interesting, paidhi. Is there any means of detecting this technology in operation?”

“Anything that transmits, I would suspect, can be detected by the right instrument, but this location device primarily receives, one assumes, and it is something outside my expertise. I ask the aiji not to reveal its existence to the Guild at large. I am sure of my own staff, that they will not reveal it, and I may have to order it suppressed, even destroyed—but numerous installations fallen from the heavens and sitting in vegetable fields across the aishidi’tat are clearly within general notice.”

Tabini smiled, this time with darker humor. “Tell me, paidhi-aiji, is my son expert in this technology, too?”

“This, one doubts the young gentleman has theorized, since he has never been that far lost—aboard the ship. But we did track him—in his wanderings aboard. He may know this.”

“A wonder,” Tabini said, and the smile generously persisted. “Ask your sources these details, paidhi-aiji, and report to me. Should we worry about the ship-aijiin’s motives in bestowing this technology on the world?”

“I think they originated this notion in support of your administration, aiji-ma, or I would be exceedingly alarmed. I believe that they planned to turn this system over to you, if they had been able to find you in the first place—which I think they could not, since you had no such device. I think it was done to be able to point to precise spots in the world and track events, and to report to you where your enemies were. The station’s ability to see things on the planet is very detailed. This system helps describe the location of what they see. The world is now numbered and divided according to their numbers, and one does not believe this would comfort the traditionalists.”

“Indeed. And by this they have found your brother.” Tabini stretched his feet out before him, seeming thoroughly comfortable.

“The lords will assemble for ordinary business; committees will enter session. Your office is functioning. You are seeking to reestablish the shuttles.”

The summation. Change of topic. Or introduction of another one, which might wend its way back to the first. “Yes, aiji-ma.”

“A very reasonable priority. But what will the shuttles bring down to us when they fly? More of these mysterious landings?

Technology in support of these devices? Persons? Ogun-aiji has been in charge of the station during the ship’s absence, and we have had no contact with him for an extended time. One has not had great confidence in Yolanda-paidhi before that: her man’chi, so to speak, is still not to us, and not to this world, and one has, while finding her useful, never wholly understood her motives. She has been resident on the island, in daily communication with Ogun-aiji, receiving orders from him. It seems possible Ogun-aiji’s intentions might also have drifted beyond those we understand.”

“It does seem time to ask Jase what these items do, and to have a thorough account, aiji-ma, of what sort of machine they have dropped from orbit. There seems no great harm intended. I still believe these devices were intended to support your return—”

“Or support Mospheira in an invasion?”

His pulse did a little skip. “One doubts Mospheira would be willing to undertake it on any large scale. Operatives, perhaps. But that my staff did not find any opportunity to tell me—Tano and Algini had the devices, and had them before my return.

Unfortunately—they are in the field at the moment one would most want to ask them questions. Banichi does not know.”

“Guild reticence, perhaps.”

It was a proverb, that the Guild never admitted its assets, particularly in the field. In that light it was entirely understandable. If there seemed an advantage in having it, hell, yes, Banichi would take it, and settle accounts later. As he had. As Tano and Algini had. Whatever Ogun had been up to, Ogun had not cut his on-station staff out of the loop. There was that.

But coupled with the landings, and who knew what other changesc Tano and Algini had given him no explanation, presumably had given Banichi and Jago none, nor any to Cenedi, as he concluded.

“The aiji is justifiably concerned,” he said, “to find they have sent technology down here that my office would not approve. The paidhi is concerned. My on-station staff knew things that were not communicated to me. This is all I know, aiji-ma, and one is distressed by it.”

An eyebrow lifted. Some thought passed unspoken, behind that pale stare. The aiji said: “The paidhi’s office will report when there is an answer. And this time I will receive the note.”

Reference to a time when absolutely no message of his had gotten through, officially speaking. The gateway to communication was declared officially open again. At least that, even if the aiji held some thoughts private.

And he had a job to do—reins of power to gather up, fast, before Ogun’s unilateral decisions—and the questions proliferating around these foreign devices landing on the mainland—did political damage to Tabini, or societal damage to the atevi. Whatever atevi got their hands on—they were damned good at figuring out. And that might already be in progress, in some distant province, if not directly at Tabini’s orders.

He had done enough, himself, casually letting the aiji’s heir get his hands into technology unexamined in its effects. Of course there was a network. Wherever there were computers, there was very soon a network. Small-area networks existed within offices, small nets had aided factories, had shared data within departments.