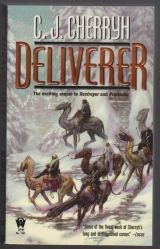

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

"Deliverer" by C. J. Cherryh

1

Morning—a very early morning, with the red-tiled roofs of Shejidan hazed in fog, presenting a mazy sprawl in the distance beyond the balcony rail. A definite nip of autumn edged the wind that swept across the table and flared the damask cloth.

Ilisidi, aiji-dowager, diminutive of her kind, and very frail, seemed little affected by the chill. Bren Cameron, opposite her at the small breakfast table, swallowed cup after cup of hot tea and tried to still his shivers.

The dowager, seemingly oblivious to the slight breeze, slid several more eggs onto her plate and cheerfully ladled on a sauce Bren would never dare touch.

They were without bodyguards for the moment, or, rather, their respective bodyguards were sensibly standing just inside, out of the wind. The balcony was high enough and faced away from likely sniper sites, so that here, at least, one had no reason to fear bullets, assassins, or remnants of the recent coup and counterrevolution.

“Lord Tatiseigi will go home soon,” Ilisidi said conversationally—one never discussed business over meals. This was a social remark, ostensibly, at least.

“Indeed, aiji-ma?” They had come here from Lord Tatiseigi’s estate, which had suffered extensive damage in the fighting, damage ranging from its mangled hedges to an upstairs bedroom missing its floor. It would not be a happy homecoming for the old manc though it was a triumphant one.

“He has so many things to arrange,” Ilisidi said. “Carpenters, plasterers—stonemasons.” An egg vanished, and Ilisidi rapped the dish with her spoon. “Do trust the white sauce, nand’ paidhi. Have the fish. You look peaked.”

Frozen was nearer the truth, and sauces were a minefield of alkaloids delectable to atevi, and potentially fatal to humans, but Bren obediently slid a little of the fish offering onto his plate, and spooned white sauce atop it, a sauce kept hot, despite the bitter gale, by a lid and a shielded candle.

The breakfast service was silver lined with hand-painted porcelain, hunting scenes, each piece exquisite and historic.

Everything was historic in Ilisidi’s apartment, which no rebel hand had dared touch, even when everyone had believed that Tabini-aiji was dead and Ilisidi was unlikely to return from space. Tabini had lived, and she had returned, and those who had thought differently were, at the moment, running for their lives.

Bren himself had a small guest quarters within Ilisidi’s domain, inside the Bu-javid, that massive city-girt fortress which housed no few of the lords of the Association. Herein, inside a building that loomed above the city of Shejidan, resided the aiji himself, the lords, the officials, besides their offices, the legislature and their offices—the complex sat atop its hill in the ancient heart of the city.

The fortress and the city, not to mention the continent that spanned half the world, were newly back in the aiji’s hands, and they, Bren Cameron and Ilisidi and their respective bodyguards, were newly returned from their two-year voyage, dropped down to the world in support of Tabini-aiji. The two of them had come down from the sterile security of a steel world, where the only breezes came from the vents, to this balcony, where nature determined the temperature and the breeze, and Bren found the change of realities—and the intervening few days of revolution—both exhilarating and a little unreal, even yet. The paidhi might freeze and shiver, but this morning he enjoyed the sensations, the sight, the tastes– the very randomness of things.

Not too much randomness, thank you. The random shooting had died down in the city. The Assassins’ Guild had sorted out its internal affairs and begun to function politically, which meant more stability, enforcement of laws and, indeed, elimination of certain individuals bent on civil unrest. As a result, they two, and the rest of the country, could draw an easier breath, and sleep at night in relative confidence of waking up the next morning: Bren personally welcomed that sort of scheduled regularity, even bloodily achieved.

“Tatiseigi will go home,” Ilisidi reiterated across the rim of her teacup, “and I shall go with him. He will need our advice.”

Significance penetrated the shivers. “One understands, then, aiji-ma,” Bren said. “One will make other arrangements immediately.”

“Arrangements are already made for the paidhi-aiji’s residence.”

Ilisidi’s cup touched the cloth and a servant appeared, to pour more tea. “Nand’paidhi?”

Tea, she meant. Bren set down his ice-cold cup and the servant whisked another, steaming hot, into its place, before pouring.

“Thank you, nand’ dowager. May one ask—?”

“Tatiseigi will inform you of the details himself, doubtless, or at least leave a message, but he intends to make his own apartment available for the paidhi’s usec under current circumstances.”

“One is honored.” Thunderstruck by the old man’s action was more to the point. Tatiseigi’s apartment was, indeed, where he had once resided, in Tatiseigi’s long absence from the capital, and he had once thought of it as home; but a good many things had intervened—a very great many advancements, and a great many violent things. He had dealt with Lord Tatiseigi, who did not approve of humans, or televisions, or any other human-brought plague on his traditions, and who had housed him in the meanest rooms in his great house on his return from space.

And Tatiseigi was willing to invite him back? One would be very glad to believe that the old man had suddenly suffered a complete change of perspective about humans, had determined that he was an admirable and acceptable being.

Or the sun might rise in the west. The old man had something up his sleeve, surely. “One is extremely honored, nandi, and I shall express it to him.”

“Understand, this residence would remain available in my absencec” Ilisidi ladled sauce onto fish. “c except, one regrets to say, my grandson, who finds his personal residence greatly disturbed, has set eyes on it.”

Disturbed was an understatement: Tabini-aiji’s personal apartment had been a battleground during the coup: certain of his servants had died there, blood stained the carpets, there had been a fire set, and certain priceless artworks had been damaged or stolen.

The premises was under thorough restoration and examination for security problems.

Meanwhile the paidhi’s own apartment, on loan from the Maladesi, had been a case of don’t-ask on his arrival: a clan of difficult man’chi, claiming to be distant relatives of the Maladesi, had occupied it, had been instrumental in getting access to that floor during the aiji’s entry into the Bu-javid—since they had taken out political rivals, supporters of the other regime, in the process—and in point of fact—the aiji had not found it politic to toss them out of the residence, never mind the fact they had jumped themselves to the head of a very long waiting list for Bu-javid residencyc it was a mess, it was an absolute mess, and the end result was—the paidhi had no apartment until the aiji finessed the Farai out of it. And the aiji was too busy finessing his own living quarters to worry about the paidhi-aiji.

“So Tabini will lodge here,” Ilisidi said, “while the aiji’s official residence is restored and renewed. Tatiseigi, for his part, is very anxious to get back to Tirnamardi and assess damages there. It seems a convenient arrangement, that the paidhi should lodge in the Atageini apartments.”

Which meant that the Farai were either persons that Tatiseigi of the Atageini would not invite—possible: they were southern, not high in Tatiseigi’s favor at the moment—or the Farai were still barricaded into his apartment in hopes of getting concessions out of Tabini.

He was still amazed at Tatiseigi’s hospitality toward him. “Dare one ask,” he began cautiously, “whether this gracious gesture was his lordship’s idea, aiji-ma?”

Ilisidi chuckled and lifted an eyebrow. “We did suggest itc considering my grandson’s impending residency here, and considering our assistance in the Atageini defense, which has indebted Tatiseigi, when he will acknowledge the fact. In very fact, our attendance out at Tirnamardi will prevent another sort of disaster. Tatiseigi will bully the artisans. The artist he most wants will certainly quit if not kept in good humor, we well know. So we will be there to prevent the old fool from threatening the man’s life.”

One could only imagine. Ilisidi was in for a lively stay under Tatiseigi’s roof.

But to have something like his own quarters again: that was glorious news. He was delighted. But on a second thought, he was not the dowager’s only guest, and that other individual’s security was a matter of deep concern to him. “And is Cajeiri going to Tirnamardi, too?”

“No.” A sip of tea, and a thoughtful frown. “No, my great-grandson will stay here, with his parents. That will be safest.

Far too many things in Tirnamardi invite his ingenuity. And best he have time with his parents in exclusivity, to allow bonds to formc”

He ventured no comment at all, nor deemed it proper. Hundreds of years humans had been on this world, and as long as there had been paidhiin—interpreters and intercessors between atevi and humans—and as close as he had gotten to the culture, atevi had still kept certain things unsaid—as was their custom, to be sure.

Certain things were either never commented upon, a matter of good manners, or remained entirely outside the realm of the paidhi’s dealings, and the bringing up of their children was a major zone of silence: neither Banichi nor Jago volunteered information in that regard, and when he had asked, Jago had professed ignorance and indifference on her own partc a clear enough signal it was not a topic she favored.

But he wanted to know—not only professionally: since he had taken up dealing with the boy, for two significant years of his life—since he had acquired an entirely unprofessional fondness for a boy he in no wise wanted to damage or misdirect, he wanted to know.

The dowager only added, “We have cared for him too long. His sense of association needs time to form naturally, and in appropriate directions. This is his chance, in a field of diminishing chances, and best take it.”

Sense of association: that emotion atevi felt that wasn’t friendship, or love, those two most dangerous human words. What Ilisidi referred to as diminishing was the opportunity for Cajeiri’s forming his own sense of attachments, which constituted an ateva’s internal compass in relationships, a feeling central to a healthy personality. A human could only ask himself how wide a window of opportunity a child had, to begin to form those necessary—and reciprocal—bonds, and if there was a point at which that window shut, after which they were left with one very confused young boy.

Certainly the ship where Cajeiri had just spent the last two years had held no youngsters of his own species: more, it had contained far too many opportunities to form ties to the human population, youngsters who used the terms friend and birthday partyc “Should I seek residence entirely elsewhere, then, aiji-ma?” he asked. He was through eating. The portions were far too much for his frame. The warmth the food and the tea provided was fast fading, especially in the contemplation of a separation from the household. “Should I take myself and my staff down the hill to the hotel—or perhaps all the way to my estate for a time? I could conduct certain business there quite handily, aiji-ma, if more distance would—”

“Our compliments to your sensitivity and grace, nand’ paidhi. No, that will not be necessary. We are confident that a removal down the hall will suffice. My great-grandson still needs your advisements, and your good sense. We should not all desert him at once, and doubtless—I have absolutely no doubt at all—he will attempt to contact you, whatever the difficulties. One also foresees he will attempt to politic with you and his father, playing one against the other: you know his tricks far, far better than my grandson. A surrogate for his father—oh, indeed, you have been that, paidhi-aiji, over the last two years. One rather assumes that you have formed some sort of bond to my great-grandchild as well.”

“One must confess it, aiji-ma, one does feel such a sentiment.”

“Well, well, one must necessarily let that association grow somewhat fainter, particularly for public view. I have spoken to my great-grandson regarding this. And to my grandson. One trusts the paidhi absolutely understands.”

Indeed. He was saddened to have it confirmed it had to be.

But Cajeiri had had far too much to do with humans, the last two formative years, between six and eight—and now he well understood that if the dowager needed to back away and let the boy form ties to his parents, then he had to back away and let Cajeiri become what he had to be, to be adult, sane, and healthy—not to mention heir to his father’s power, ruler of the atevi worldc aiji of the aishidi’tat, with all that meant. Aijiin didn’t form upward attachments, or they abandoned them increasingly as they grew up: the boy he saw as just a boy was, if he was ever going to rule, going to have to change—would have to drink in other people’s manchiin like water, and attach himself only to his inferiors.

Would have to become cold enough, calculating enough—to rule, to judge, to administer. To be impartial in decisions, reasoned in debate, and ruthless with his enemies, as enemies not only of himself, but of the people he representedc it was not a mindset a Mospheiran wanted to encourage in a child, but it was what Cajeiri was supposed to become.

So they had come back to earth in various senses. The change had to come, and for the boy’s own psychological health, the right signals needed to run down the boy’s nerves, and that set of instincts needed to find answers that a human just couldn’t give himc not and produce a sane ateva.

At least, he thought, this time someone had warned the boy ahead of time that his life was about to be jerked sideways. Cajeiri wasn’t going to like it. That was also part of his mental makeup: he defended himself, oh, quite well.

And for good or for ill, he told himself, waiting for the dowager to finish her last cup of tea, he wouldn’t be totally out of reach, when, not if, the boy needed him.

Great-grandmother, a Stability of One, was having breakfast with the Lord of the Heavens. That was marginally more fortunate to say than to remark that Great-grandmother and the Lord of the Heavens were having breakfast, an Infelicity of Two. There was, of course, a compensatory flower arrangement on that table on the drafty balcony, and the bodyguards, five in number—only Jago had come with nand’ Bren, which was odd—made a Felicity of Sevenc All of which was to say that Cajeiri was not invited to that table, but he was sure it was not just the numbers. He was sure it meant the grownups were discussing him, because it would have been a great deal less fuss over all to have provided him a chair at the same table and made felicitous three, would it not?

As it was, he had a quiet breakfast with his bodyguards, Antaro and Jegari, who were brother and sister, and only a little older than he was. They were Taibeni, from the deep forests of the slopes of the Padi Valley, and they were not at all accustomed to city manners, so it was a relief to them, he supposed, not to have to stand in the hall and try to talk to the likes of Cenedi, Great-grandmother’s chief bodyguard, or Banichi or Jago, who were Bren’s, and terribly imposing—Banichi was actually a very obliging fellow, but Jegari was quite scared of him: that was the truth.

His guard liked the informal ways of Taiben. He, on the other hand, was accustomed to servants at his elbow, oh, indeed he was.

He had grown up first with his mother and father, in the most servant-ridden place in the world, and then with great-uncle Tatiseigi, who was a stickler for propriety, and finally with Great-grandmother, traveling in space with nand’ Bren, in a vast ship far too small to hide him from proper manners. It was first from Uncle Tatiseigi and then from Great-grandmother he had learned his courtesies: they were very old-fashioned, and insisted on the forms even if they secretly didn’t believe in the superstitions.

He had been locked up in Great-grandmother’s apartment for two years on the ship, and she had made sure he would be fit to come back as his father’s son and her great-grandson—his left ear had gotten positively tender from all the thwacking.

He had left the world when he was six. He was now in that awkward year before nine, that year so infelicitous one could not name it, let alone celebrate its birthday in any happy way. That was very bad fortune, since it was the only birthday he had had a chance to have with his new associates on shipboard– Great-grandmother had finally agreed he might have a small celebration, and then he had not even gotten that much, because of the crisis—because they had plunged right down to earth on the shuttle, leaving all his shipboard associates behind and spending the next number of days getting shot atc Well, except he had gotten to ride in the engine of a train. That had been exciting.

He was very precocious in his behavior and in his schooling: nand’ Bren said so, so he was already as good as nine, was he not?

He could speak Bren’s native Mosphei’, as well as ship-speak. He could speak kyo, for that matter, which only a handful of atevi or humans could do. He had learned to ride and shoot before he went into space—well, he could ride, at least: he had learned to shoot on the ship; and Great-grandmother had taught him how to write a formal hand in all the good forms and made him memorize all the lords of the Association and their rights and dutiesc and proper addressesc So he was really not too uncivilized to be at their table, was he?

He was not yet fluent enough in adult Ragi to dance across the nuances, as Great-grandmother called it. Using it could still get him into embarrassing trouble. And it was ever so hard just to sit and listen when really interesting questions were bubbling up into his head.

But he could at least parse everything that was proper at that table. Bren, a Stability of One, he most-times referred to very properly as Bren-nandi. Bren’s guards were, together, Bren-aishini, not just aishi, the association of Bren-paidhi, and his guards were aishishi, meaning the protective surrounds.(1) So, there! He could handle the basic forms of the adult language and remember to put in the compensatory numbers—that was at least sure, and people did use the easy forms, well, at least they did informally, or when they were pretending to be informal, which was a layer of pretending which he understood, but he was not supposed to use it with adults or he was being insolentc How could one learn the whole nuance of adult Ragi if no one would ever talk with him?

How could he be i-ron-ic if people only took him for a baby who used the wrong form because he had not a clue?

1. A note from Bren’s dictionary: The number of a noun or verb is always considered In-Its-Environment, which means the kabiu of the item is subject to the surrounds and Number Compensations such as seating and arrangements. This is complex enough. Rendering human views in Mosphei’ contains words with sentiments strongly reflecting human emotions—for example: “motherhood” and “friendship.” To give equal expression to an ateva speaking Ragi, which contains constructs for his own biological urges, any accurate translation of his thoughts into Mosphei’ must, for the human hearer, create special forms to note the mental direction of those feelings. For example, Ragi has “respect” in general but also specifies “familial-respect” or “aiji-respect” or “newly-met-stranger-respect,” each of which evokes feelings which resonate through the ateva psyche. Ragi is meticulously specific in many sensitive terms in which a human, reading the translated words, must struggle to remember contain emotional impact at all. A mentally healthy ateva feels, in saying, for instance, “aiji-respect” as powerful a sense of emotional bonding as a human would experience in saying, “my dearest friend” and “my own front doorc” The central difficulty of Ragi translation rests in the fact that while specific words can be translated, the human brain hearing them, unless cued to do so, does not readily attach sufficient or correct emotional subtext.

Numerically auspicious and inauspicious aspects present yet another subtle resonance, sometimes a presentiment of luck or foreboding.

He wanted company other than Great-grandmother’s staff. He wanted people he could surprise and make laugh.

He missed Gene and Artur, his ship-aishi (one could not call them aishini, or at least one had certainly better not do it in Great-grandmother’s hearing.) He had gotten more used to young humans than he was to atevi over the last two years, and still found it strange to look across his own informal table and see two dark, golden-eyed atevi faces, so earnest, so– That was the heart of his domestic problem. Antaro and Jegari felt man’chi toward him, a sense of duty and devotion so passionate it had drawn them away from all their kin to live in a city they hardly understood. It had brought them to risk their lives for him on a dangerous journey, with people shooting at them, and he knew he should feel a pure, deep emotion toward them in turn—great-grandmother had said on the ship that he was in real danger of never developing proper feelings, which would be a very unhealthy thing; and that once he was back in the world, proper feelings would come to him, and that what he felt toward his aishini would be ever so much stronger than anything he had ever possibly felt toward Gene and Artur, because that feeling would be returnedc in ways Gene and Artur could never return what he needed.

But on that point everything broke down and hurt, it just outright hurt, because Gene and Artur did care about him, in their human way, and he knew they still cared—in their human way. He knew they had been hurt when he left—they must have hurt the same way as he hurt, and no one would acknowledge it.

Aishimuta. Breach of association. Losing someone you never thought of losing.

Losing someone you could never even explain to anyone, someone that no one else thought you could care aboutc there ought to be a word for that, too, even worse than aishimuta. He had never thought he would lose Gene and Artur. He had been so confident he could just bring them home with him when he had to go down to the world, and that sensible grown-ups would, with no problem at all, agree to the idea of their living with him.

That had been juvenile thinking, had it not?

And once their coming down to earth had fallen seamlessly into place, so his plans had run, of course he would bring Gene and Artur to his father and his mother and tell his parents what wonderful associates they were, and how clever, and unusual, and all those things, and the whole world would understand it was a wonderful arrangement. He would have Gene and Artur with him forever, the way his father had nand’ Bren to advise him about humans, and everything would be perfect and happy.

He had been a fool. Great-grandmother had not quite said that word, but he was sure she had disparaged his plans in private and spared him her opinion, only advancing that argument that there would be someone who would appeal to him when he reached home, and that he would know that person, or those people, in a situation that felt right. According to her, there would be no question what he feltc all the things everyone told him he would feelc And for one moment, he had almost had it. When Antaro and Jegari had declared for him that day in the forest, with so many dangers around him, he had accepted it—he had been surprised by their gesture, for one thing, and he had believed that something special would flash down from the heavens or something—he didn’t know exactly what. But he was open to it. He had tried.

But he still waited to feel it take hold of him.

Now he felt uneasy in his connection with Antaro and Jegari, who had done so much for him. It was true they were comfortable companions and he felt at ease with them. He knew what their expressions meant as if he had known them all his life, and he could guess what they were thinking with fair accuracyc that was something. They were faces like his own, black, golden-eyed, and naturally subtle around strangers. They were not at all like aboard the ship, where no one stood on ceremony—where he could all but hear Gene shout down the hall in that reckless, wonderful, irreverent way, “Hey! Jeri!”

He was Jeri. He had been delighted to know it was a proper human name, too, the way it was a proper atevi one.

And oh, he missed that voice, and that irreverence, and that sense of fun. And he felt so guilty and ashamed of himself for it.

Antaro and Jegari were a steady warmth, not a spark and a flash.

They never offered a really wicked glance, the way Gene would look at him to let him know some adventure was brewing and they were about to risk trouble. Jegari and Antaro would ask, cautiously and solemnly, “Do you think your great-grandmother would approve, nandi?”

And that was the way his life was supposed to be. Solemn.

Cautious.

Well, he supposed he had had adventures enough for one year at least, riding on mecheiti and buses and trains and being shot at—he had shot a man himself, because he had to, to save their lives, but he had no wish to remember that part, which was not glorious, or an adventure, or anything but terrible. He thought it ought to have changed him—but it was mostly just not there in his thinking.

Certainly a lot of people had died. That had been horrible, too.

And he knew that just the journey had changed things around him—more, that it had changed him in ways he was still figuring out.

But the thing that really hit hardest was how close he had come to losing everyone he really knew and relied onc the last remaining: Great-grandmother, and nand’ Bren, and their aishini.

All his associations in the whole universe were, if not broken, at least stretched painfully thin, and people wanted to shove others at him, fast, while he was alone and desperate. That was a nasty thing to do. A few meant well—Great-grandmother, and nand’ Bren. But lords were all but battering at the door to introduce him to their own children, and he just would not see them: Great-grandmother at least supported him in that.

He had learned that not everything was that sure in his life: that was the second lesson he had gotten on this voyage. Having lost the heavens, he had come within a breath of losing everything that was ever going to matter on earth, too, and right now he was stranded with no chance ever to get back to the heavens, because the shuttles were not flying, and might never, if certain people had had their way. It had been close, on that score, but great-grandmother and Lord Bren had taken precautions, and the shuttles were being protected—for which he was very grateful.

In recent days he had been alone, and scared of being alone, and of dying alone, although dying was something he still could not quite figure out—how it was, or how it worked. And he had met Jegari and Antaro, who had some promise, if they weren’t so rule-following.

And they were going to get the shuttles flying again, so there was still hopec But he was not supposed to think about Gene and Artur coming down here, and worse, he had to face the possibility they might not ever be able to. Now he understood how very politically difficult it was going to be, to bring humans anywhere near him, and how people would be watching him and suspecting him. He saw how people all over the world had blamed nand’ Bren for everything that had gone wrong, which was just unfair, but that was how people had wanted to think, because it was easier to blame humans for everything that was the matter, and now for people to blame any association he had ever had with humans for any peculiarity he would ever have or any bad thing he ever did—that was just wrong.

It was wrong, and he could not go for years being good. It just made him so mad he could just– But one could not. One had to be calm, and act like an adult to get one’s way. And most people were coming to a different opinion about nand’ Bren, now, so maybe the trouble would die down.

But it could take years.

Great-grandmother had told Uncle Tatiseigi that he had had enough association-separation in his young life so far; and great-uncle Tatiseigi had argued he had come out of it perfectly fine for a boy in an unfortunate year of his life. Uncle Tatiseigi had told Great-grandmother he was not unbalanced in his head: that much was nice of Great-uncle. But then uncle Tatiseigi had added that he certainly would have been unbalanced if he had stayed in space much longer, that there were clear signs of improper thoughts, and it was a damned good thing he had come down here among real people.

That had made him mad, too, but that was Great-uncle.

And at least he knew his elders worried about him, and great-uncle did sincerely worry that he had grown up under questionable influences. The problem was, Great-uncle had very firm opinions about what was right for him, and unluckily for him, Great-grandmother and Great-uncle were not that far apart in their arguments. Uncle Tatiseigi would like him never to mention humans again. Great-grandmother wanted him to give up even thinking about Gene and Artur, and she was hoping, too, that he would forget about them coming down to earth, ever.

And years and years could pass, and they might quiet down about bad influences, but that would be long after he had grown up sane and normal and Gene and Artur had turned into human adults he would never even recognize if he saw them.

That hurt. That thought already wore a deep sore where it lodged and was not going to heal, because he never intended to let it. It made him resolve one thing, that the moment he did get any power, he was going to bring anybody he wanted down to the earth and keep them there.