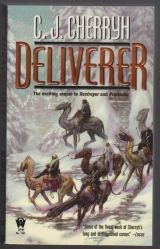

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

We shall reach him, Bren-ji. We shall use every persuasion to bring him to the coast.”

“Every persuasion,” Jago echoed, meaning, he was sure, a modicum of force, if need be, to overcome Toby’s presidential orders.

Toby knew Tano and Algini, once they were face-to-face. He would trust them. So it would be all right—better that they learned where Toby was than to let some dissident faction find out and set out after him, them and Toby none the wiser: seeing what Banichi meant in that well that we do know, Bren let the brandy warm his stomach, and let go a pent breath.

“One trusts,” he said, “one trusts, then, that everything possible is being done. My gratitude, nadiin-ji, my gratitude to Tano and Algini, and please express it to them, if you can. One also understands,” he added, because the amount of distress his security would bear if anything did go wrong at this point was beyond easy expression, “one clearly understands that Toby’s position is fraught with hazards by no means within our control. Baji-naji, we will win this throw.”

“We are closer,” Banichi pointed out, “than any potential enemy in the south. And we have the estate staff already at hand.”

“True,” he said, and had a second sip, feeling better. “What a morning, nadiin-ji! But the young gentleman is behind doors, we are fairly well toward reaching my brother, and one is extremely glad to have the dish up again.—May one ask, nadiin-ji, what Jase-aiji meant? What is this, dropping equipment?”

There were looks, a little reserve. That was unusual.

“Are these things the paidhi-aiji needs to know?” Bren asked, “And are these matters the aiji himself does not know?”

“Possibly he does not,” Banichi said judiciously. “We do not know, ourselves, the nature of these devices dropped. The equipment came with Tano and Algini. We have carried it throughout, but not turned it on—on their advice, not relying on any outside gift, and not having any assurance of all its capabilities, in the haste of our departure, and in an uncertain situation. We do not trust without knowledge.”

“It is much the same as location on the ship,” Jago said, “but we are told they can locate a position for the user anywhere in the world, relative to a map. If it had seemed useful at any point, for the ship to know precisely where we were, we understand we might have provided that location. But we never used it. We have no knowledge how they have tracked Murini, or if they have means to do so, but until we have heard nand’ Jase’s voice, we have had no assurance how things stand aboard the station, or whether nand’ Sabin has resumed authority. That is the sum of it, Bren-ji. Since we have never doubted where we were, we have never used them.”

Understandable that his security, with enough on their hands, was not relying on some untested system handed by authorities aloftc not when, until now, they had had no way to be sure who was in charge up there.

“Are they with you now, nadiin-ji? Or did they go with Tano and Algini?”

“Tano and Algini have two. We have three.”

Three. “And the landings?”

“We have no knowledge of those,” Banichi said, “nor have Tano and Algini mentioned any such thing, Bren-ji. We do not believe they would have failed to say if they had any such information.”

Considering the sieve that was Tatiseigi’s security net, and the way their communications had fed into the enemy’s, entirely understandable his security had wanted to trust only what they knewc knowing there was very little the station could do to assist them, without some dramatic action that might scare off the people that were moved to rejoin Tabini-aijic Thank God they hadn’t dropped anything in on Tatiseigi’s estate.

Half the force gathered there would have run for the hills.

But they were a different issue than this equipment Tano and Algini had brought with themc like the locators they’d used on the station and the ship.

The network that would have to support it—if not the landed devices—was a staggering implication. Satellites. A grid all over the globe.

“Do you suppose Presidenta Tyers has such devices provided him,” he asked, thoughts cascading through his mind on various tracks, “and that he provided the same to Toby? Were we tracked?”

“Certainly we did not have any knowledge of it,” Banichi said, “but did not the Presidenta have access to the shuttle crew?

Clearly, he might have received such equipment at that time, and he might have had some understanding with nand’ Toby—which we were not told, for reasons of security.”

“If the Presidenta involved my household in some dangerous enterprise, he could have told me,” Bren muttered, and added: “But so could my brother have told me, nadiin-ji.”

“Toby-nandi surely knows what you and we would say to his involvement, Bren-ji,” Jago said, not without dark humor. “But one doubts he would be dissuaded by the Presidenta or by the paidhi-aiji.”

It was true. It was damned well true of Toby. “Well, so, what are these things, ’Nichi-ji? Entirely like the locators?”

“A network, nandi, and since communication with the station requires somewhat more power than our ordinary equipment provides—one does conceive the notion that these reported devices dropped here and there by parachute may be connected to this system, perhaps supplying power to transmit.”

“Communication without Mogari-nai. But no vocal capability.”

“One suspects, at least, that the system is more than receptionc since they claim to know where nand’ Toby is.”

“Curious. And I was not to know.”

“One believes, Bren-ji, that there was some amount of secrecy connected to its usefulness,” Jago said, “perhaps that it is something already known to Mospheira, about which they might have advised us—but we received no information there, either.

Tano and Algini themselves suggested we refrain from using them—they foresaw a certain doubt about the station-aiji and the ship-aijiin, whether we might rely on them.”

Guild reticence. Guild suspicion. Some third party gave them equipment, and damned right they weren’t going to use it unquestioned.

But there were those who would.

“If Tyers has it, the island might manufacture it, given their communication with the station has never faltered.” The picture began to come clear to him, that Shawn’s administration might well have had a global mapping project going with the station, at least from the time the aishidi’tat fragmented itself and Tabini left powerc Shawn, damn his hide, had been tracking things, had been in close communication with the station, and had neglected to discuss that system with his former employee—namely him? Ogun had provided his staff with the equipment, maybe not telling Shawn that they were doing it? And Shawn didn’t tell them if they were being tracked from orbit, given the things might be two-way?

Oh, things were in their usual tangle of suspicion.

Trust had broken down completely, was what. Bet on it. Murini had been in charge, at that hour, and Tabini’s retaking the capital had not even been on the horizon when Tano and Algini had come into possession of these tracking devices. Shawn might have assumed they were going to set the dowager and the boy in the aijinate. And damned sure Shawn had sweated when they’d crossed the water and stayed untrackable.

He understood why his bodyguard hadn’t wanted to turn the equipment on—with all it potentially connected to. He wasn’t that anxious to use it himself, not utterly understanding what it did, or who it informed.

But if Toby was on the system—somehow– And if Jase was in a position of authority up above and Ogun was playing straight with Jase and Sabin– “Pacts,” he said, “pacts apparently exist between Shawn Tyers’ government and the station. They’ve permitted the installation of this equipment. Tyers very likely knows. And the station possibly violated secrecy in giving these units to Tano and Algini—considering the mess we were going into. Considering that the dowager might end up ruling the aishidi’tat, with whom it could be argued certain treaties had been trampled on—the station did not want us to feel betrayed by this system. And Shawn, for whatever reason, would not breach security to inform us this was going on—possibly because he thought he was doing enough putting it in Toby’s hands, possibly against agreements he had with the station, perhaps otherwise. Toby didn’t tell us, because Shawn had asked him not to. He is the Presidenta. He would have argued with Toby that it was best I not know—because he was asking Toby to undertake a second mission he had no wish for me to know about.

And Tyers may or may not know you have that equipment now.

One would expect he does know—if Jase has been telling him all he knows. But Tyers may not have the capacity to track—if it exists.

That ability may reside only with the station, from their vantage, with their receivers.”

“Humans,” Banichi said dourly, “can be puzzling.”

“No man’chi, nadiin-ji. Toby knew I would argue to the contrary.

And Toby wished to do this, for his own pride.”

There was no atevi word for a person who would step outside man’chi, defy a prestigious relative, and seek personal risk because he’d been waiting for a chance like that all his cautious life. No word, but Toby, damn it all.

So neither the station nor the island had been idle while the continent had been under Murini’s rule—they’d been working hand over fist to do something. Those landers out there were for something, and there were satellites up there tracking them—had to be.

And if local farmers took to hacking up the mysterious landers with axes—that was not a desirable situation, either—no knowing what contamination they might let loose, for one unhappy result.

But there were others possible. Deaths. Resentment.

Suspicion—that he had to answer, somehow, when neither the station authorities nor his former President had leaped to provide him answers.

He had an inkling what the mix was that had given his bodyguard pause—the certain sense there was something human going on, and that if they just didn’t turn the damned things on, they could postpone upsetting the paidhi-aiji and adding one more vector to the problems of the aishidi’tat. Just settle it on the atevi plane, first. Then let the paidhi-aiji take on the foreignersc Let the paidhi-aiji get the truth out of the station-aijiin.

Let Tabini sit in authority again, and let the world get back to normal.

He intended to have more information, from Shawn and from Jase, that was dead certain. And he wanted Toby safe, and if the station’s little secret project—spread all across atevi skies in a plethora of foreign numbers—could get Toby back to shore in one piece, good.

Another sip of brandy.

He was going to have to explain it to Tabini, this business of foreign equipment parachuting into local fields and frightening the wildlife. He was going to have to say that this had gone unmentioned for days, and there were installations from space dropped all over the continent, for unknown reasons.

More, he was going to have to explain to the superstitious and the uncounted atevi institutions that humans had divided their world in numbers. God help him.

“Did they mention anything else it would be useful for me to know, nadiin-ji?”

“That was the sum of what we were given, Bren-ji,” Banichi said.

“We all kept it close. It was my own decision. It seemed a possible point of controversy, in certain quarters.”

Understatement. And he was, Banichi had always informed him, an absolutely wretched liar, by atevi standards.

“Perfectly understandable,” he said. “It is understandable, ’Nichi-ji: by no means trouble yourself. We both agree I do not lie well.”

Banichi gave a visible wince. “Indeed. All the same—”

“No fault, ’Nichi-ji, no fault at all.”

He so rarely scored one on Banichi, and the brandy had made itself a warm spot, in a confidence that, however tangled the skeins of information around him, he had finally begun to get a real sense of what had been going on—what had been going on all during the time that Yolanda Mercheson had run for her life and the station in orbit had started cooperating closely with Shawn Tyers on measures they could take to protect their assets.

The Treaty of the Landing had taken a beating during the last decade, but it was still what kept humans and atevi trusting one another enough to keep out of each others’ affairs, and out of each others’ territory. It was the basis of peace and order. And the station and Tyers had had something going that hammered it hard.

He didn’t think Tyers would in any wise contemplate invading the mainland. Human agents on the mainland would be a little damned conspicuous.

But Mospheira might have contemplated bringing Lord Geigi and his people down in the one shuttle they had left in orbit, and letting Geigi go after Murini.

Now there was a thought.

Well, thank God it hadn’t gotten to that. Thank God Tabini had stayed alive, and the relative framework of the aishidi’tat had bent, but not broken.

A close call. None of the alternatives had been good ones. But if any had been put into play, one hoped Shawn would call them off quickly, so they could all pretend nothing had ever gone on.

And if Toby and Tano and Algini had locators, they stood a good chance of finding each other in all that water. Dared he think that?

He hoped so. He fervently hoped so.

Delivered to one’s own door by Banichi.

Escorted to one’s own chambers within those doors by his father’s bodyguard, and watched like a criminal. Cajeiri was disgusted.

He had been so close to reaching Gene. He had talked to Jase-aiji, and when he had, all the memories of the ship had come flooding back, the very textures and smells and the details, down to the ribbing on the lights and the pattern of the floor tiles—suddenly, in his mind, he had seen Gene’s face, with his pale skin, not unpleasingly brown-speckled across the nose, his eyes, a remarkable muddle of gray, green, and blue– his hair, which was brown and dark, and curled generally out of control– He had already begun to lose the details he tried to hold in his head, but they were back, now. Artur’s face, narrow-nosed and with a chipped front tooth—Irene’s, dark as an ateva, but brown, and eyes darker than her face, scarily dark, full of thoughts– Golden eyes around him, now, two sets of purest golden eyes, worried-looking. Antaro and Jegari seemed sure they were at fault, which was absolutely stupid. It was stupid the way everyone down here seemed anxious to sop up blame when he did anything at all.

For a moment overwhelming anger welled up in his throat, anger enough to strike out and break something, but mani had taught him better, so he choked it back.

Oh, he had anger enough for a sharp word to his father’s guards out there, but mani would do far more than whack him on the ear if he let fly. If mani-ma were here, which she was not. She had deserted him, given him up to his father. Everyone had deserted him, everyone that he actually wanted to be near him, everyone but these two, who sat staring at him as if at any moment he would have some incredibly brilliant answer for their collective embarrassment.

Banichi had not had two words for him, beyond the fact that he was delivering him to his father’s care, and that he was not to be out and about in the future without Guild in attendance. It was absolute disaster.

And Jaidiri-nadi had shown up in person to take custody of him, and he was sure Banichi had gone back down to the party, where he would inform nand’ Bren the boy was back in his room, under guard.

It had been fun down there until– Until the business with the phone call, and he had brushed past nand’ Bren, and pushed right in front of Bren’s staff—he knew better, but he had done it, and he knew he had gone far past even nand’ Bren’s patient limit. He knew what mani-ma would say about what he had done. He had known it before he did it. But the bitter truth was—he had assumed he could get away with it. He had pushed too far, and Bren, Bren, that he relied on for patience, had turned him in.

And that was that. He all but shook from anger, in the realization that from now on he would be watched—lucky if he could get out of his room, let alone the apartment. It was not fair.

Nothing was fair. Nothing in his life was the way he wanted any more, and now Banichi, of all people, who used to play games with him, had turned on him and told him not to be out without real Guild in attendance, and Bren-nandi was furious, and probably would talk to his father.

And Jaidiri was absolutely furious. He had gotten past Jaidiri when Jaidiri was in a meeting with staff, he had planned it that way, and now Jaidiri knew it. Probably Jaidiri was in a great deal of trouble with his father, new in his job as he was: Jaidiri was professionally embarrassed. His new servants, Uncle’s people, too, were embarrassed. Everybody was upset with him, because everybody was going to get into trouble for letting him get outside.

Well, so was he upset, but nobody cared that he was upset.

Nobody at all cared what he thought. Mani-ma went away with Uncle, and Bren moved out, and his father and mother had seized control of him, but just installed him as one more obligation on their busy schedules. They paid no attention to him except at dinner-times, when they spared an hour to talk to him.

Damn, damn, damn! He would say the word and nobody cared to stop him. Nobody cared at all: they just shoved him in a room to be let out only for supper, and they embarrassed him in front of Jegari and Antaro.

He flung himself down at his desk and picked up his sketch of the ship and flung it. Papers scattered, and Jegari and Antaro were too wise to move to pick them up. He wanted to rip things in shreds.

And they just stood, part of the disaster, finding nothing at all they could do to help.

“One desires some of that cake from last night, nadiin,” he said finally, which gave them an excuse to leave, as they could do and he could not: they could pass the guards at his door without being tracked—even if nobody gave them keys, such as other guards had.

They could at least go out and do something useful. He remembered the cake from last night’s supper. He had liked it. He wanted some sort of comfort for an upset stomach. He wanted meanwhile to calm down and use his wits. He could hear mani-ma telling him that he was a fool when he was angry and nobody wanted to take orders from a fool.

Maybe they could filch keys. It was not like keys on the ship, which were cards if they were not personal codes or thumbprints: they never had figured how to get by the thumb locks; but the Bu-javid keys were metal, and people carried them, and might be careless if he kept his eyes open.

He could all but see the passages on the ship. Gene and Artur, and him, with their breath frosting in the light Gene had, and Gene saying, “We can go wherever we like. I know how.”

He picked up his own papers off the floor. He straightened them into order, and tried not to choke on his own breath.

How could he have forgotten any of the details that had just come back to him? How could he have forgotten details about Gene?

His own memory was fading in this place, after hardly more than a handful of days, and he might forget other things, important things. He might start speaking only Ragi, and lose a lot of his ship-speak, if he was not careful.

That was the plan, was it not? This was such a different place, and the things he forgot were the very things the grownups wanted to take away from him. That was what they were doing—taking things away piece by piece, so he would forget, and be what they wantedc Well, he would refuse to forget. He made a little note: he drew a pathetic little figure beside it, that was Gene, and gave it dark hair.

He wished he could draw better. He would draw his room on the ship, just the way it was, with the simple little bed, and the bath, and the things he had had in the cabinets, things he liked, which he had not been able to bring down with him—he’d just packed a few changes of clothes, was all, but everything he had up there was still up there, over his headc And it would be for years, as far out of reach as the moon.

Even the moon was a place, when they were up there. The earth was somewhere else. Everything he knew was different up there. It was wider. Warmer. It had nooks and levels and places he could explore or just sit for hours without guards breathing close behind him.

He missed it all. He missed it terribly.

He drew Artur and Irene, stupid, simple little figures, just to remind him of the details he had gotten back.

And with a knock and a rattle at the door, Jegari and Antaro came back to the room accompanied by one of the under-cooks– of course it would never be just a piece of cake they got—no, no, it was one of the cooks, who personally served him tea, juice, and a generous plate of the requested cake. He found it unappetizing now that he had gotten it with such a fuss, but he insisted Jegari and Antaro share some with him, and have some juice, and they seemed happier because they thought he was. The cook took the dishes, and left the three of them alone again.

At least the shakes had stopped, and Cajeiri finally found it in him to apologize to them.

“One is very sorry, nadiin-ji, for getting you in trouble.”

“We would wish to take the blame, nandi,” Antaro said.

“You shall not! I shall tell my father it was my idea, and it was.”

His anger rose up again, and he remembered what mani-ma had said about orders from fools. “But we did find out about the dish, and we did talk to Jase-aiji. So we gained something.”

“Indeed,” Jegari said faintly.

“Jase-aiji is an ally of nand’ Bren,” he informed them, “and used to live here on earth. He parachuted down. He was lucky to survive. Then he flew back with the first shuttle. Nand’ Bren and he are very close allies. And Jase-aiji keeps his word. He will talk to Gene, and Gene may well send me a message when Jase-aiji calls nand’ Bren back. So it was not a failure.”

They looked impressed with that reasoning, and he felt comforted by the look on their faces. Most of all, when he thought of those familiar names, the ship became a place again, in his head, and would not immediately go away.

When you have atevi around you, mani-ma had said, you will find their actions speak to you in an atevi way. You will find a degree of comfort with them that you will not find with your human associates. You will see.

He had not believed that prediction, not for a moment. But, truth be told, there was something that tugged at his attention when he faced Jegari and Antaro, the same way that when mani-ma spoke, or when his father or mother did, his own intentions slid, and his insides wanted one thing and his head wanted another.

But a third thing, inside him, resisted any trick that was going to separate him from his earliest real associates, and that part he clung to, reminding himself that he was not an infant, to be distracted from his intentions by some bright bauble, or a diverting voice. Forgetting was what the adults all planned for him, and it was too bad Jegari and Antaro had fallen right into that plan of mani-ma’s: they deserved an untainted connection to him, but he was never quite sure that someone had not put them up to their sudden declaration of man’chi, be it an ambitious father, or the lord of the Taibeni, or mani herselfc Which was so wretched and horrid a thought it stained everything and made him angrier than he was.

He was not happy, being pulled in that many directions, but it was what it was, as mani herself would say. And he would not just sit down and react like a baby. He had his ship-plan. And he remembered, and he knew now the trick was to think of the names and the faces and remember everything they had done. Every night before he went to sleep, from now on, he would put himself back on the ship, face-to-face with those he knew were loyal to him for no reason but their own choice. Anything else was suspect, since it came to him with increasing force that if someone wanted him to do things, and here he was, because of his age, all ready to open up to the first ateva who just happened along into his lifec Well, someone as clever as his great-grandmother and his father would make sure their own people came along and got next to him earliest of all, would they not? And other people were ever so eager to shove their offspring his direction. It was like one of those movies, where people wanted to marry off a daughter, only he was the daughter, and it was not marrying, it was much more serious: it was getting into his man’chi, forever, which just made him mad.

And if he ever found out Antaro and Jegari had been pushed into it—he would be furious. Not with them. But with someone.

So there. He had figured that out almost from the start. He had recovered from the first astonishment that Jegari and Antaro had joined him, and they were well-intentioned, and good, and he was sure it was a safe enough connection for him to have, and a natural and useful one: the Taibeni Ragi were relatives, after all, and it was a way of making sure Great-Uncle Tatiseigi could not claim him exclusively—Uncle was at odds with the Taibeni, and the other way around, which meant he was the point at which they had to make peace, to deal with him: it was good for both sides, he thought, and they could not have stood off the Kadagidi without both sides working together.

But it meant that he was on his guard about guards and servants any other relative appointed, and he was entirely on his guard about the ones Uncle gave him, and he certainly wanted no one from his mother’s Ajuri relatives.

If there was anybody under the Bu-javid roof he truly trusted, it was nand’ Bren: Great-grandmother said nand’ Bren had no real feelings of man’chi, but she had said, too, that what Lord Bren had in him was something else, a human thing, but steady, and centered very firmly on certain people. One could never predict entirely what he would do, but one could rely on it to be in certain people’s interest, sometimes entirely against their will.

So, well, was that not like Gene? Great-grandmother relied on Lord Bren, and while Lord Bren did things that just set uncle on edge, he was still reliable. Safe. Connected. Why was it not the same as man’chi?

But oh, he wished he had not showed out so notably at Lord Bren’s party. Most of all he wished that Lord Bren had not gotten angry with him. He had deserved itc he just had not expected it, because it took a lot to make Lord Bren angry.

And maybe mani-ma was right and nobody but another human could understand what nand’ Bren thought, but surely Lord Bren would understand better than anyone how he felt about his associates up on the ship. Lord Bren knew that strong feelings could exist between humans and atevi: he knew Lord Bren slept with one of his own staff, which was, he suspected, completely scandalous, even if he were not human—everybody tried so hard to pretend it was not going on, but it was, and he had never dared ask Great-grandmother whether she thought that was all right.

Now it might be forever until he could ask her questions like that. He certainly had no intention of asking his parents, or of letting on that he even knew it went on. He did at least know that such a relationship with staff had gotten past great-grandmother’s very close scrutiny, and he had at least an inkling that Great-grandmother and Cenedi had a close relationship, too, whether or not it was proper. And he was certainly not going to mention that relationship to his parents.

He was not moved to have such ties himself down here on the planet. He hoped he never would be, well, not for a long time, because that was one more person who would try to complicate his life and tie him to earth. But he was sure if there was anybody as lonely as he was, it had to be nand’ Bren, who was different from everyone around him, and if Bren needed to sleep with Jago, or Great-grandmother needed Cenedi—that was all right, if it made them happy. When they were together, they were—really together.

Happy. He could feel it. And he had had just the littlest notion how it felt to be that connected—before Jegari and Antaro, and before they all had to leave the ship, and before people started shooting at each other, proving only that atevi could be just as stupid as the humans they had rescued out in space. And it all was designed to mess up his life, which had been as happy as could be up on the ship.

He had not even the ability to call outside his room, now.

Communications were justc backwardc on the whole planet, except the Assassins’ Guild, and maybe over on the island. The net they had used on the ship did not even exist on the planet. It certainly ought to. If he had Gene, and they had computers, it would exist in short orderc Except nothing connected to anything, and why it failed to connect was something he could find out inside an hour—if he were connected to a library. It was all just disheartening.

He thought about it, and thought through the things he knew how to do, and finally inquired, via Jegari, through his uncle’s guards outside, whether his father would see him alone. Well, one of his two guards would go to inquire: they were cautious.

But: Yes, the answer came back, after a lengthy wait.

In the meanwhile, in all hope, he had had Jegari bring out his best coat—he immediately put it on and lost no time at all. He exited his rooms with his own guards, swept up the one of Uncle’s security who had delivered the message, and who escorted him as far as the door where his parents’ security waited.

His father, it turned out, was having tea with his mother.

He had rather have dealt with one at a time, but in the terms of his query—he supposed it counted as alone. He covered his dismay with a little bow, and in great propriety, waited for a signal. His mother gave it, and he came to them and presented himself with a second little bow to his mother and a third to his father.