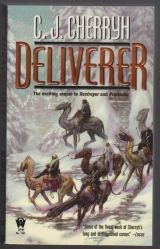

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“A maid. A member of the staff,” Banichi said. “Pahien. The paidhi may remember her.”

“One remembers her,” Bren said. Indeed he did: a woman who found every opportunity to hang about the young gentleman’s quarters. Ambitous, he’d thought, someone who wanted to work her way up in the staff of a young man with prospects.

“She is probably on that plane,” Jago said darkly, and Banichi: “If they controlled the heir to Malguri—and anything befell the aiji-dowager—”

“The dowager may be in greater danger of her life than Cajeiri,”

Jago murmured. “It is entirely in the interest of the kidnappers that he stay alive, in that theory. And the dowager is going to Malguri. One does not approve.”

It was not the conclusion he had drawn from the same facts.

“Possibly they wish to coerce the dowager to take certain measures they favor, nadiin-ji.”

“That would be a dangerous move on their part, Bren-ji.”

To attempt to deal with herc damned certain it was. She was a knife that turned in the hand—her husband had found that out.

“If she were dead, on the other hand, the lord of Malguri would be a minor child—in their hands.”

“Balking the aiji in Shejidan as well,” Jago said. “If the aiji were to disinherit his heir, it would have calamitous effect in the west, and no effect at all in the East. He would still inherit Malguri.”

“Has Cenedi advised her against going? Will she remain inside Malguri?”

“Advised, yes, but by no means will the dowager leave this matter to her security, nandi,” Banichi muttered. “Cenedi cannot persuade her. Our Guild is already in Malguri Township, moving to secure various of her assets, but it is not even certain that our landing at Malguri Airport will be secure. One hopes to have that news before we land.”

He had not thought of that point of danger, but it was good to know the old links were functioning. “Can Guild possibly intercept that plane on the ground?” he asked.

“If Caiti were only so foolish as to land at Malguri Airport,”

Banichi said, “it would be easy. Cie, however, will take time to penetrate. And one regrets we will not have time. Planes fly faster above than vehicles or mecheiti can proceed in the weather there.”

“Then they will land unchecked, nadiin-ji?”

“Very likely they will, Bren-ji,” was Banichi’s glum assessment, “for any effective purposes.”

“Is there any chance of our going in at Cie?”

“They will surely take measures,” Banichi said. “We cannot risk it, Bren-ji.”

The Guild was not given to suicide. Or to losing the people they were trying to protect. Almost certainly there were Guild resources in Cie or moving there, but Banichi was not going to say so: the only inference one could draw was that there were not enough Guild resources there to protect the dowager or to effect a rescue.

He nodded, quietly left his staff to their own devices, and returned to the dowager’s cabin.

There he sat and brooded, among shaded windows, with only his watch for a gauge of time or progress. Eventually, after a long time, the young men moved to rap on the dowager’s door, doubtless by prior arrangment.

Cenedi entered the cabin, then, glanced at that door, then said to Bren: “The plane we are tracking, nandi, has entered descent, not at Malguri’s airport, nor even at Cie, but at a remote airport up at Cadienein-ori.”

“Still Caiti’s territory, nadi, is it not?”

“And a short runway, nandi,” Cenedi said. Cenedi did not look in the least happy, and must have heard something on the com, because he left for the rear of the plane immediately.

The dowager meanwhile emerged from her rest, and settled in her chair.

“The plane will land at Cadienein-ori, aiji-ma,” Bren said.

“One is not entirely surprised,” the dowager muttered. “They must trust their pilot.”

It was a scarily short airstrip for that size jet. Bren knew that much.

He imagined that if the Guild had scrambled to get assets as close to Cie as possible, they were now moving upland by any available means, to get to that small rural airport. One was not even sure roads ran between Cie and Cadienein-ori: in much of the rural East, lords had roads between their primary residence and a local airport, but freight might move entirely by air, these days, and the configuration of the roads was more web-work than grid.

One often had to go clear back to some central hub to go to a place only a few miles across a line of hills from where one was.

Cenedi returned after awhile, and bowed. “They have landed, aiji-ma, at Cadienein-ori. They undershot the runway, attempting to use all of it, and the plane seems damaged and immovable. There is only one runway. And it was iced, with heavy snowfall.”

No way for anyone else to get in, with a large plane blocking the runway. No way for them to land, certainly, except at the regional airport, in Ilisidi’s territory: their going in at Cie was no good, now.

And whatever the Guild had just revised their plans to do was now blocked by a disabled plane.

By accident or arrangement, Caiti had gotten farther out of their reach, and out of reach of Guild intervention. It was not to say that the non-Guild protection the lords of the East had at their disposal was unskilled. Far from it. And now how did anyone get in, with the weather closing in? One hoped that they could land.

“So,” was all the dowager said to that news, except, “Would the paidhi-aiji care for a brandied tea?”

“Indeed,” he said, agreeable to anything that pleased the dowager and settled her nerves.

So he waited, full of questions, knowing he would not be the one to ask them, and believing that the dowager herself might not have all the answers. Caiti had most of them at the moment. And at this point they hoped the young gentleman was in Caiti’s hands.

“Thank you, nadi,” he murmured to the servant, and accepted the glass. He took the merest sip and waited for details, if details might come.

In a moment more, Nawari came in, and bowed.

“Nand’ dowager,” he said, and with a second bow, “nand’ paidhi.

Three cars met that plane. The emergency slide had deployed. But there was some further delay to remove the luggage from the plane and take it with them in the airport bus. All passengers seem to have left.”

“Effrontery,” was Ilisidi’s comment, regarding the baggage. “Was there sight of my great-grandson?”

“Not that was entirely certain, nand’ dowager,” Nawari said.

“Members of the party were shaken up in the landing. And precisely where that car went afterward, there is as yet no report.

It left southward, as one would going to the Haidamar or the Saibai’tet. One small bus pulled away from the column, its whereabouts and direction seeming to the southern route, as one would go to the lowlands. It may be Lord Rodi leaving. Or Lady Agilisi.”

“Pish,” Ilisidi said. “We know. We have every confidence my great-grandson is wherever Caiti is.”

“Indeed,” Nawari said, “aiji-ma, it seems likely that he might be.

The majority has gone on eastward.”

“Tell Cenedi we will go to Malguri as planned. Tell the staff prepare. Have that car tracked.”

“Nandi,” Nawari said, and went back to deliver that instruction.

It might or might not be a diversionc but the dowager’s strength had its limits. They had to believe the boy was there, that he had not been taken off somewhere else. The dowager chose to believe it.

At least, Bren said to himself, that plane was safely on the ground, and if the car had gone south—the direction of either of Caiti’s domains from that highland airport—at least the plane was down, and there had been no ambulances.

Under present circumstances, however, the Guild was not in position to act, and no one could be surprised that the occupants had simply driven away, no one preventing them. There were three minor airports besides that in Malguri province. Cadienein-ori was not the largest, not by a hundred feet of runwayc not unless they had improved it since the last time he had sat on the Aviation Board.

So effectively Cadienein-ori was shut down at the moment, with that very large airplane stuck in the snow somewhere on the only runway that would remotely accommodate any airplane bringing Guild to address the problem.

And if the Guild intervened with too much fire and smoke and failed—it would alienate the very people most likely to be of use getting Cajeiri out alive: the neighbors and rivals who most naturally would cooperate to Caiti’s disadvantage. In the East, there were always rivals. Shejidan had grown up in the west and gathered provinces around it, an anomaly of politics and centrality and old history of associations, but it was not a pattern the East had adopted, not to this day.

And one didn’t get anywhere good in the East by forgetting that.

If either Rodi or Agilisi had left the party, it might be because that lord had gotten cold feet. And that might be an asset, a chink in the conspiracy that might be useful. Or it might mean something else, including even spiriting the boy away elsewhere. It needed observers in place to know that.

Would Tabini be moving his own agents into the situation in greater force? Was there a second plane behind them?

Maybe. But Tabini had already made his opening move, in sending him in with Banichi and Jago. They were the aiji’s eyes and hands in this situation. Aside from them, one reasonably expected everything would work through Cenedi and his men, men who operated here because they came from here and knew the rules. If the aiji did send Guild out under the Shejidan seal, things they needed on the ground would mysteriously break, fail to appear, go missing, or simply fail to reach a destinationc that was the way of things. Even Ilisidi would make no heavy-handed moves of Guild in the East, and the few other lords who did employ Guild employed them mostly quietly. Getting her great-grandson out—no lord alive would deny her the right to try, and nod quietly and move to her side if she proved she could do it without annoyance to themselves.

But it was all very delicate. Power rested in the will of a very loose confederation of lords, and she was one of them, but there was no council in the East. There was no legislature. There were no widespread and unifying laws. Every estate of every lord of every province was a feudal holding without an acknowledged central overlord, except the ancient dominance of Malguri. Certainly not all the neighbors would have agreed with someone kidnapping the heir of the lord of the West, as they called the aiji in Shejidan—and if someone disturbed their local way of doing things by bringing war to the region, the ones who did it would gather ire upon themselves.

But it was not guaranteed they would get help from anyone at all.

So that plane was down safely. People had left it alive. Good hope to this hour it was not a diversion, and the boy was where they thought, and not handed off via that mysterious car to some plane bound for southern territory. In that, the weather became their ally. Getting anything in or out was not easy.

In the meanwhile he sipped his brandied tea, and Ilisidi gave orders for a light meal all around. Her young men hurried about business in the galley, and soon food issued forth from the galley, going fore and aft. The presentation for him and the dowager was immaculate, the linen spotless, and the sole topic of conversation during what amounted to an extravagant teatime was the weather and the reports of snow at Malguri and across the uplands—much as if they had been planning a holiday, nothing more strenuous in the trip.

One complimented the young chef—who, indeed, was also part of the dowager’s security team: one complimented his choices, one enjoyed tea, and really wished not to have had the earlier drink—fatigue had the brain fuzzing, the ferment of emergency and impending crisis proving just too much after a night short of sleep.

They were not that far from Malguri. The paidhi had to think; and he still had no idea whether something was proceeding on the ground, some Guild operation to rescue the boy, or how Jegari was faring, or what Tabini might be up to while they were suspended between heaven and earth– Or what they were going to do next, if somehow they had missed the boy at the airport, followed a lure instead of the real thing and let Murini’s faction get its hands on Tabini’s son– The dowager held a conference with Cenedi, after tea, one that named names, notably those of her dinner guests, and inquired about transport, and the reliability of the service at Malguri Airport.

“A bus will be waiting, nandi,” Cenedi assured her.

The bus. God. The bus up to Malguri: that was one tidbit of information, that they were indeed going to the dowager’s stronghold and not the long way around the lake to the other airport—a long trip in; but he had forgotten the upland bus, and that road.

He excused himself aft, looking for more substantial information.

Jegari was sitting up—had had a sandwich, being a resilient lad, though he was a little subdued, and probably muzzy and confused with concussion. Banichi and Jago got up from their seats and proved amenable to questions.

The answers, however, were simply that they knew no more than before—not unlikely, if a Guild operation was in progress, and still short of its mark. They would not radio it hither and yon about the country, nor would this staff. Their own plane was, indeed, about to start descent toward Malguri Airport, near the township, and somewhat below the fortress that ruled the province.

“We do what we can,” Banichi said. “We have taken precautions.”

“When we leave the plane, Bren-ji,” Jago added, “stay with us.

Nawari and Tasi will see to the boy. Cenedi will be with the dowager.”

Meaning he was to move quickly and not encumber his staff; and that they did not take for granted a safe move between airplane and bus. He entirely understood, and went forward again, where the dowager was busy putting on her coat.

He did the same, no time to be wasted.

He had hardly finished that operation before the nose of the plane began that gentle declination that warned they were going down. He settled in a chair, as the dowager did, and falling into her mood, he said nothing at all as the plane descended, asked no questions and expected no answers. The plain fact was, staff believed they were going in to a landing in which the dowager theoretically controlled the ground, and from which presumably Cenedi had had satisfactory responses, but they took nothing absolutely for granted.

Nor, he told himself, should the paidhi delay a moment once his feet hit the ladder.

The plane arrived in a gentle landing and with a slight oddness on the runway: snow, Bren thought; but with the sound of the tires as they came to a full stop, he thought, in some dismay– ice here, too.

They stopped, eventually, and taxied back and around. When the plane came to rest and the dowager got up; Bren got up, taking his computer with him. Meanwhile the thump of doors and hatches advised them that the crew was scrambling to get the plane opened up and the passengers needed to move out at all deliberate speed.

He led the way back into the central aisle, and picked up Banichi and Jago.

“We shall go down first, Bren-ji,” Banichi said, and he made no objections: the dowager was too precious to risk drawing fire, in the case something was wrong here—one hoped some of Ilisidi’s people were in place outside. He felt the cold waft from the door as it opened, and they went back to the rear, where Ilisidi’s young men stood. The ladder had pulled up to the plane in an amazingly short time, considering it was not located near the terminal; and he drew in a breath and exited, sandwiched between Banichi and Jago, moving fast to get down into the shadows below the blinking running light from the nearer wing and the tail.

A half-sized bus arrived out of the darkness and stopped with a squeal of tires. Two uniformed Assassins bailed out and held the door open, and Bren climbed the steps. A clatter on the ladder above announced another party debarking, which, by the time they had gotten into the back of the very small bus, proved to be Jegari and his two protectors.

Last came the dowager, to be settled into the front seat, with Cenedi and the rest of the crew, which filled the little bus. There were no headlights. There were still no headlights as the bus pulled away and headed away from the plane, gathering speed, across the unmarked snow.

They crossed what might be the bus’s own tracks, passed a wire gate at high speed, skidded on ice on a shallow turn, banged a curb, and then the headlights flared on.

Bren exhaled a breath, realized he had the computer clutched in both arms like a panicked schoolboy, and studiedly settled back into the bench seat, with the fever heat of his bodyguard one on each side of him. The side of the terminal loomed as a gray stone wall in the headlights, then vanished sideways as they swerved again.

Malguri’s regional airfield was nothing like the metropolitan surrounds of Shejidan. The whole assembly was a huddle of stone buildings, a garage, a freight warehouse, snow-veiled and capped with white. Snow was piled on either side of the roadway, and the snowfall was gaining on the most recent scraping. Malguri sat at altitude, and winter was in full spate here.

They reached the outer road, and took the fork that led to the highlands. Breath frosted the windows. Wipers beat a frantic time against falling snow, and the engine hiccuped and growled alternately as it struck deeper snow—God, he knew this vehicle.

They had never replaced it. They had gone to space. Traveled to the stars. And this damned bus lived.

“Have we heard from staff at Malguri, nadiin-ji?” he asked his bodyguard.

“They are waiting for us, Bren-ji,” Jago assured him. “There will be food, and a bed tonight.”

Food and a bed was not the sum of his worries. “The young gentleman—have we learned anything, nadiin-ji?”

“Guild is pursuing the situation in the north, nandi,” Banichi said.

Upward bound, then. They whined their way through a drift, made it onto the road, bumping and jouncing.

The drive from the lowland airport to the heights of Malguri had figured in shipboard nightmares—it was still that potent. And that had been in good weather. He had repeatedly seen the view of a particular chasm and felt the vehicle tip under him, one of those edge-of-sleep falls that associated itself most firmly with folded space, the terror of losing oneself in nowhere.

It couldn’t possibly, he told himself, be as bad as he remembered it. And the driver would be more cautious with snow on the ground.

By no means would Cenedi tolerate any real risk to the dowager. It was simply the memory of an islander grown too spoiled, too used to paved roads. And they had the injured boy with them tonight—his injuries now well-wrapped, but by no means should he be jostled.

The bus bucketed fairly sedately along the first snowy climb, headed up small canyons, along reasonable curves. He ought, he thought, to be ashamed of himself—hell, he knew mountain roads: he’d grown up with them, well, at least on holiday. In that long-ago day he’d been anxious about his situation, was all. He’d transferred that anxiety to the busc The vehicle suddenly swerved, bringing empty air and distant scrub into his view beyond the headlights, as the bus tipped. He’d swear the wheel had found a road-edge gully under the snow. And ice didn’t improve the situation. He heard the wheels spin as they made the corner.

“God!” he muttered, and heard Cenedi sharply caution the driver and threaten his job—unprecedented.

Things settled markedly, after that, a number of sharp curves, but nothing so alarming—until they veered off on the Malguri road and nosed up toward the hills.

Bren’s foot crept to the stanchion of the seat in front, braced hard. Banichi, beside him, had a grip on the rail of the row in front.

They hit ice. The driver spun the wheel valiantly this way and that and recovered, then accelerated, for God’s sake. They rubbed the snowbank, and in a bump and a shower of snow they plowed through a small drift, with empty, snowy air on the left hand.

Cenedi leaped to his feet and, very rare for him, actually swore at the driver.

He could not hear the driver’s response; but one began to think that perhaps the driver had a reason for anxiety, in the dowager’s unannounced return.

Not to mention his own presence. The paidhi-aiji was as popular here as the plague.

The bus slacked its speed, however. Cenedi stood behind the driver, and one of Ilisidi’s young men had gotten to the fore of her seat, braced between her and the windshield.

There was something wrong, something decidedly wrong.

Banichi, too, got up, eased out and went forward, leaving Jago behind, as the bus reached a slower and slower speed, proceeding almost sedately now.

The driver, whose eyes Bren could see in the rearview mirror, looked wildly left to right.

“Down,” Jago said, beside him, and suddenly flattened him to the bench seat. “Bren-ji, get down.”

Ilisidi’s guard was, at that moment, shielding her with their armored bodies.

The tires, Bren thought, flattening himself on the seat, were highly vulnerable. Welcome home, was it?

Jago slipped down and squatted down in the aisle next to him, her hand on his back. “We have contacted Djinana,” Jago said, naming one of the chief operatives in charge of Malguri Fortress, where they were bound. “He has contacted Maigi, and others of the staff, and other staff at the airport. They have the road secure.

They met traces of intrusion onto the road, but these are now in retreat. None of us believe that Caiti would be such a fool. This was a local piece of banditry.”

“Banditry!” Welcome to the East, indeed. That a handful of individuals severed man’chi and set up independent operations– my God, he thought: the mental shift, if not psychological aberration, that that act required– And in Malguri District, itself, no lessc “Very ill-considered on their part,” Jago said.

“Against the dowager, Jago-jic”

“One doubts they are from Malguri itself. More likely, they emanate from among the neighbors, and have taken advantage of the dowager’s absence.”

He took her reading of the psychology on faith, faith that it would not be wishful thinking behind that assessment, not from Jago, who could at least feel the undercurrents she met. He was all too aware at this precise moment of missing a critical sense, being totally blind to what others read. He tried to figure their situation, lying there with the possibility of shots flying over his prone body, trying to reason where such bandits would come from—from among the neighbors, some overambitious second nephew with no prospects? Or some wildcard from among the reasonable neighbors, who just wanted to wink at such activity in a neighbor’s domain and gather profit from outright theft? That might have worked in ancient times, when there was open land. One did not move in on the vacant lordship of the aiji-dowager and expect to prosper, not even when Guild affairs had been in a tangle and a usurper had overthrown the dowager’s grandsonc But anachronism was the heart and soul of the East. If it was going to happen anywhere, it would certainly turn up here, where modern plumbing was still controversial.

“The driver has heard rumors in the township, almost certainly,”

Jago said. “Your staff puts no great credence in these threats of banditry—if such there be at all, Bren-ji. There may have been mutterings. Some associations may be greatly disturbed by the dowager’s return.”

“One understands so, Jago-ji, but—to come on her land—”

“Once the dowager is home, there will be phone calls among the neighbors; and there will assuredly be apologies from the bus company.”

About the wild driving, perhaps. Or about not advising the dowager’s security that there might be a hazard, and forcing them to get their information from the dowager’s estate—after they might well have run into an ambush.

They were still all crouched on the floor—except the driver and dowager, except those physically shielding the latter. The boy Jegari was kneeling in the aisle with the rest, supported and protected by two of Ilisidi’s young men.

“The driver is operating on rumor?”

“We do not know the accuracy of his fears,” Jago said. “That will be determined. Certainly he should have stated his misgivings to the dowager’s security at the outset, and did not. That is a fault.

That is a grievous fault.” The bus swayed and skidded slightly outward around a sharp curve. “Instead, most charitably, Bren-ji, he hoped to get us there alive without betraying certain individuals—so that the issue would never arise. One would surmise these people talk much too loudly, and the driver has gained at least peripheral knowledge of ambitious behavior in the district.”

Ambitious behavior. Not banditry. So he guessed right in one particular. “So what the driver heard might lead under the certain doors, do you think?”

“It will certainly be interesting to know. One doubts the company will get its driver or its bus back for a number of hours, Bren-ji—possibly Cenedi will send it back to bring your wardrobe, when it arrives on the next plane. Perhaps one of the house staff will drive it. The driver may need protection. One will attempt to determine that before sending the man back.”

The dowager had been away for two years, completely out of touch, while the district around her estate thought they had found a power vacuum, that was what. The realization that she was alive, and resuming her old power, had tipped a balance back to center, leaving some, possibly including Caiti, caught in an untenable position. The noisiest of the rest had now to decide whether to try to pretend nothing had happened—a dangerous course—or they had to make a move to become powerful.

And how that meshed with the overt action of Caiti and his companions—that was a serious, serious question.

And if certain of the neighbors, namely Caiti, thought they could make no headway with Ilisidi, and if they were still operating on their own, the dowager’s strong responses might drive them to more desperate actions, like linking up with Tabini-aiji’s opposition, specifically the restless south, Murini’s supporters—if they could demonstrate they had Tabini’s heir, and were willing to play that game– Dark, desperate thoughts, with one’s face down against the seat cushion, and the bus tires spinning in a drift of snow.

If the kidnappers could demonstrate the dowager’s power had declined, it might, for one, tilt the ever-fickle Kadagidi, the clan of Murini’s birth, Tatiseigi’s near neighbors, right back into the anti-Tabini camp, at the very moment the presumedly anti-Murini faction in that clan was in charge and negotiating with Tabini for a political rapprochment. And at the same moment, the East might start to disaffect and join the association of the south, the aishidi’mar.

It could break the whole damned business open again and create another armed attack on the aiji’s authority.

Not to mention that Cajeiri was at the present in hostile hands and they had quasi-bandits in the neighborhood.

Oh, this was not good.

He saw Banichi move farther forward, encouraging the driver, whose progress was far more sedate than before. Turn after turn, an incident or two of spinning wheels and a slow climb, and Jago looked up, and got up onto the seat.

“Malguri,” Jago said, and as Bren lifted up and tried to see the gates, Jago’s hand pressed him right back down.

“Let us clarify the situation first, Bren-ji.”

He stayed put, deprived of all sight of what was going on, until the bus slowed and turned on what distant memory read as the very front approach to the fortress.

Then he made another move to get up, and Jago did not intervene. He sat up, seeing, like a long-lost vision, a place that had been home for a brief but very formative time in his career, the nightbound stones just as grim, snow-edged, now, the upper windows alight—there were no lower ones, in this house designed for siege and walled about with battlements. Ilisidi stood up as the bus came to a halt, her security parting so she could have the view from the windshield. The front doors of the house opened, and staff came outside, bundled against the cold, as the bus opened its door and let Cenedi out.

Ilisidi came next, Cenedi offering his hand to steady her steps.

The boy Jegari got to his feet, with help, and managed to get down the aisle as Bren worked his way forward behind Jago.

Down the steps, then, in the dark and the snowy wind, a breath of cold mountain air, and carefully swept and deiced steps. The inside gaped, with live flame lamps.

Malguri, heart and soul. Yellow lamplight and deep shadow of centuries-old stone, nothing so ornate as the Bu-javid, or Tirnamardi. If there was color on the walls, it was the color of basalt, red-stained and black, rough hewn; or it was the color of ancient tapestry, all lit with golden lamplight. A table met them, bearing a stark arrangement of dry winter branches and a handful of stones, underneath a tapestry, a hunting scene. The air inside smelled of food, candle-wax, and woodsmoke. Servants met them, bowed. This was Ilisidi’s ancestral home, her particular holding, and the place in the world she was most in her element. She accepted the offered welcome, and walked in, and up the short interior steps.

Bren recognized those servants who welcomed them, and pulled names out of memory. He stood while Banichi and Jago surrendered some of their massive gear to servants– they would never do that in another household, not even Tirnamardi—and then turned back to deal with some issue that had occupied Cenedi as well, diverting their attention from him, as they would in no other house but the dowager’s. Other servants had taken Jegari in charge, fussing over the wounded and now wilting boy and taking him immediately upstairs—straight to bed, one hoped, after a little supper. Bren meanwhile followed the dowager to the formal hall, where a fire burned in the hearth, and more servants stood ready.