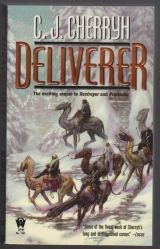

Текст книги "Deliverer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

They were asking the lad questions, likely, sharp and difficult questions, maybe getting him bandages, maybe seeing to him after a Guildsman’s fashion, very competent field medicine, making him at least tolerably comfortable. He hoped so.

He wanted to go over to a window and lift a shade to know what was going on outside, and whether his watch was right, but the lights were on full in the cabin, and he could make himself a target if there was any hostile presence out there in the dark. If there was—if there was—there must be quiet action going on apart from anything he would see. Guild in the dowager’s service and maybe Tabini’s would be moving out there, securing the area, dealing with anyone who opposed the plane taking off.

The engines whined into life. He sat down, waited. Listened to the sounds of activity on the back ramp. There was a small delay after what he took for an arrival aft.

Then from the bulkhead door Ilisidi walked in, in a dark brocade coat and with her cane in hand. Cenedi escorted her, and Jago came into the compartment and shut the door again.

Bren rose and bowed. Ilisidi walked to the centermost chair and sat down, both hands on the cane.

“Aiji-ma,” he said—he had not planned how he would meet her.

He had not even thought of the awkwardness of being assigned here by her grandson, under present circumstances. She sat now, grim and determined, and it seemed to be one of those rare occasions where staff had not passed word to staff as to what he was doing here or why he had inserted himself into a situation from which he had been—with considerable thoroughness—dismissed.

“Aiji-ma,” he said, above the sound of the engines, “your grandson the aiji sent me, urging me to assist you.”

“To assist me,” she echoed him. “Assist me to do what, paidhi? To kidnap my own great-grandson?”

Anger was in her voice. Anger, and, apparently, indignation, in a display of emotion rare except among intimates. And he was shaken in his convictions, not knowing was that indignation an act—she was that good—or whether it was real. Either case was extremely dangerous.

“A plane has left the city, aiji-ma, forgive my forwardness, probably carrying your recent dinner guests Eastward. They had not left the city before now. They left their hotel in the middle of the night, and one believes they may have the young gentleman with them.”

“Caiti,” she said bitterly. “And who of my staff and my grandson’s is dead, nand’ paidhi?”

“No one that I know, aiji-ma.”

“Yet my great-grandson is taken, nand’ paidhi!”

“His young guards were struck down, aiji-ma. Jegari is out there—” He gave a shrug to the compartment at his right, beyond the bulkhead. “His sister they left. Jegari was taken along with the young lord and escaped, trying to get help. He very much needs medical attention.”

“We are aware,” Ilisidi said flatly. And in that moment the cargo hatch slammed shut, below. “Yet you came, paidhi-aiji. Good.

Tatiseigi has returned with me from Tirnamardi, but he will not go East with us. He will resume residence in his apartments and support my grandson. He will assist in the investigation inside my staff.”

“One cannot imagine—” he began, in that dreadful silence. And in the back of his mind was a surmise that Tabini’s Taibeni staff would not take kindly to Atageini security asking questions: not to mention that Ilisidi’s Eastern staff would be obliged to answer those questions under Taibeni witness. Fireworks were absolutely assured.

“One of my petty serving staff,” Ilisidi said further, “has not answered to a summons. We assume this person is dead.”

Assuming this person had died defending the house, that was to say—or it was possible that person would die, if they turned out to be on that plane with Caiti, aiding and abetting the crime. One would not at all like to be in that person’s shoes when the dowager’s men caught up. It had to be a powerful reason that diverted that servant to Caiti’s man’chi.

The man’chiin. The connections. There were no likely ties from the aiji’s Taibeni to Cei Province.

From the dowager’s own Eastern-born staff, howeverc well possible.

“Who, may one ask, aiji-ma? Which of the staff?”

“One of Madiri’s hand-chosen staff! His import from the province!”

It was grim. Madiri himself compromised? Maidiri was still in office—and in Tabini’s household. But that chain of connection was exposed, and there were going to be questions: assume there would be questions.

He only had to explain why they had brought the injured boy aboard, if the dowager had not been informed.

“The boy Jegari, aiji-ma—his sister was knocked unconscious.

Jegari avowed himself reluctant to escape, but he hoped to get help.

He phoned to advise us and ran out—his actions seem above reproach.”

“We are aware of all his actions,” Ilisidi said in a chilling tonec not personal, he had that sense. This was not the dowager in a good mood, and there had begun to be a degree of abstraction in her eyes that one rarely saw, because one ordinarily saw the dowager with her mind firmly made up. She was thinking, thinking fast and hard, Bren decided, and he was not disposed to interrupt that train of thought.

More encouragingly—she was convincingly angry. He could not express how much that relieved his personal anxiety about her position in this.

Questions, however, were not a good idea at this juncture. He had asked all he needed to know, and he sat quietly, not willing to invade that privacy.

In a moment, Cenedi came in, and spoke quietly with the dowager, reporting, audible just above the engines. “There was intrusion into the young gentleman’s premises,” Cenedi said.

“Jegari heard it. Antaro was sleeping in adjacent quarters. Jegari went out into the hall and something hit him before he could give an alarm. He waked in the back of a plumber’s van: the young gentleman was also there, unconscious on the floor beside himc likely injected with some drug. There was one guard. Jegari laid hands on a piece of pipe and knocked the man to the floor, but he could not rouse the young gentleman afterward, and he was dizzy and disoriented. At this point he unlocked the back door from inside and jumped from the moving van, fearing to attempt to drag the young gentleman with him. He ran to a lighted office in the hope of raising an alarm and stopping the van: he asked to use the phone, after the officer in charge had used it to notify the officers on duty.

The boy had significant difficulty phoning into the Bu-javid system.

The airport security chief and his men did not immediately locate the van, or stop all aircraft from taking off. Several cargo planes were active, and there was an attempt to stop the last from reaching the runway, but it was too late—this we have from other sources than the boy, aiji-ma. Information came up the conduits too slowly, the boy not being Guild, and being under his majority. The Bu-javid operator did not cooperate with him. Two planes took off before they could stop traffic and the third, that bound for Cie, defied the tower and took off without clearance.”

“Fools!” Ilisidi said, and one doubted she meant Caiti’s lot.

“Airport security has now seized the van: they are processing it for evidence, aiji-ma. The boy stayed in the security office, refusing medical treatment in favor of staying in touch with Madiri in the apartment, evidently trusting someone from the house would come to get him—he maintains he had no word from Madiri that we were coming until the last. He ran out to intercept us on our arrival. He has a concussion, and bruised ribs.”

“Madiri again,” Ilisidi said grimly. Then: “The boy is a credit to his parents. And to my great-grandson.”

“Siegi is tending to him.” That was the dowager’s own physician.

“The boy begs to go with us. We have no easy means to send him back at this point.”

A grim, preemptory wave of Ilisidi’s hand. “Granted. Nand’ paidhi.”

“Aiji-ma?”

“We are going to Malguri,” the dowager said, and that was that.

He had already taken that for granted: if that one plane was registered to Cie, they would go to Cie or Malguri Airport, the only two with enough runway. There was nothing he could lend, either of advice or of information.

At that point the door at the rear of the plane shut with a distant, familiar thump. A wave of the dowager’s hand dismissed Cenedi, and two of the dowager’s young men came into the cabin.

The engines increased their power. The plane slowly began to move.

The young men assisted the dowager to swing a belt restraint across her shoulder. Bren belted in without a word.

Shades were still down. There was no view at all.

Whatever the dowager’s physician might have done for the boy’s comfort, one suspected more extensive treatment had had to wait until they were airborne. And if anyone had notified the youngsters’ parents or clan lord, it had not come from the paidhi’s staff. He hoped Madiri would. Or Tabini’s staff.

Their plane navigated the taxiways to the strip, and swung sharply onto the runway, gathering speed.

Lifting.

No way back, Bren thought as they shot skyward. No way back now, right step or wrong.

9

The dowager retired to nap in her bedroom once the plane reached altitudec and, knowing the dowager, she probably would nap. Bren personally wished he could catch up the hour or so of sleep he had lost, but he knew himself, that that was not going to happen, not after the desperate race to get here.

Instead he sat pat, requested tea, along with information on the boy who, one hoped, was now being treated by the doctor behind the bulkhead door—the boy was, the dowager’s staff assured him, in the best of hands, and indeed, being patched up by a real doctor.

It was more surface injury, give or take the concussion. One suspected that, during the kidnapping, the boy had been administered a sedative, which had worn off—he was twice the young gentleman’s age, and nearly of adult size.

Well, that was certainly as good an outcome as circumstances could make it. Bren felt better hearing that.

And, thinking of the breakfast he had also missed, he asked for whatever the staff might find. The young man assured him they were well-stocked, and proceeded to offer him three sweet rolls with jam, and warmed, to boot. He had those with the tea, feeling comforted.

He had one left when Jago came quietly into the compartment and sat down in the chair the dowager had left. He silently offered the remaining sweet roll to her, and she took it gratefully.

“How is the news, Jago-ji?”

“The plane to Cie is approaching the Divide, nandi.” The sweet roll immediately diminished by half, and a cup of tea arrived at her side to wash it down, with the other half. “The boy is resting comfortably enough. Staff remains with him, against any maneuver the plane may need to make.” The tea quickly disappeared. “He had a very limited view of the assailants, and still remembers nothing immediately surrounding the attack. He asked us more than once whether he should have jumped with the young gentleman in his arms. We replied that this might have been preferable, even lacking the skill to take such a fall. Broken bones would be a small price.”

A direct, an accurate answer, to a boy who might plan to enter their Guild. He understood that. “No Guild planning, surely,” Bren said, and Jago gently pursed her lips, grimly amused.

“No, Bren-ji.”

The kidnappers had made a raft of mistakesc including leaving the unconscious boys unsecured, possibly mistaking the dosage on the healthy teenager—or having no medical expertise in the company.

“Yet they evaded all pursuit and got into the air,” Jago said.

“They were not total fools, Bren-ji, nor should we expect them to be.”

“They had this planned, one thinks, before they visited the dowager’s table.”

Jago accepted another cup of tea, offered without request. “No midlander would risk this much, this recklessly. The fact that they have not involved Guild—this very strongly suggests Eastern politics, Bren-ji.” A sip of tea and a darker frown.“Still one must wonder if there may have been some approach between south and East. That remains the most worrisome possibility.”

The aiji’s Assassins had not located Murini. And the fact of Murini continuing at large was now beyond worrisome. It was a terrifying thought, that they might be decoyed eastward by the appearance of a kidnapping going east, and all the while lose track of the boy, who might have changed hands.

“Is there any cause to think this could be a decoy, Jago-ji? That the Taibeni boy could have been allowed to escape?”

“Cenedi has made inquiries in that line, and reports that a delegation from the Taisigin Marid did visit the East during Murini’s tenure—how those delegates were received, or even where they guested, was never clear. One suspects that there was contact between the southerners and certain of the Eastern lords. The aiji has made a Guild request at the highest levels.”

With a new Guildmaster in office, one whose politics were uncertain, and Algini, who was familiar with those high levels, out on the west coast, thanks to him. The thought upset his stomach, upset it extremely.

“Was the dowager aware of this visit when she invited these persons as her guests?”

“She may have been aware of it. It was difficult not to invite them, nandi, since they turned up in Shejidan, requesting audience.”

“A fishing expedition, perhaps, Murini’s contacts with the East,”

he murmured. Jago understood that metaphor. And it was logical Murini might attempt to find a door into the East: the East had always been a chancy member of the aishidi’tat. One could well imagine Murini would wish to find sympathy for himself there among those opposed to Tabini; but the trick was that Easterners were not well-disposed to each other, let alone outsiders, such as Murini was, equally with the aiji—and navigating the rocks and shoals of Eastern politics was a matter of connections as well as skill. “The question remains whether any elements of Murini’s man’chi might be directing this move—”

“Indeed,” Jago said.

“Or someone who connived with him now feels himself exposed—exposed enough to take desperate measures, considering the dowager’s return. One could be very uneasy, Jago-ji, asking oneself what the dowager might be walking into, returning to the East.”

“The dowager’s lengthy absence, rumors of her death, rumors of the aiji’s death, these might have been persuasive among her neighbors while she was gone. Indeed, nandi, issues have surely surfaced, since the dowager’s return from space– things that make particular sense to the East, and much less in the midlands.”

“But her neighbors would be concerned with the heir,” Bren said.

Cajeiri’s existence did many things—for one thing, it established Tatiseigi’s influence as major, and therefore raised the Padi Valley’s influence, Cajeiri being in their bloodline, too. It brought the Taibeni in.

And the dowager, meanwhile, being linked by fate, circumstance, and political necessity to that same Padi Valley region, might have stirred up certain individuals in the East, individuals who might not have been petted and cosseted enough by the dowager when they came to call—or who had seen reason to fear.

No, damn it, they had not cobbled a successful plot together on the spot. They had come in knowing what they planned and had used that visit to make contact with someone on the inside of Ilisidi’s defenses. This was not an impromptu business.

And beyond that, damn, it was a very deep pond to probe. An outsider had no idea what moved in Eastern politics. It was bad.

And his security thought Jegari should have taken his young lord in his arms and jumped: that was how dangerous they thought Cajeiri’s situation had become, how very dangerous it was to the aiji and the dowager and the stability of the aishidi‘-tat to have the heir in Eastern hands.

Not to mention the opinion of their visitors from the depths of space. The East hadn’t a clue what they were risking, in that regard, and would have no notion how to handle it if they ever gained the power they were after.

“Your computer is safe with the other equipment,” Jago remarked, finishing the second cup of tea. “Such clothing as I brought, Bren-ji, is shamefully dealt with. Staff attempted to assist.

There was no time. Staff at Malguri will have to press everything, but one can at least say that there are two bags of your clothes, with changes of footwear. More will follow, by tomorrow’s plane.

Cenedi assures us staff will retrieve it from the airport as soon as it arrives.”

“Excellent, Jago-ji,” he said. “One takes it the Guild is aware of this situation. Have we made any contact with the rest of the staff?”

“Regarding the Guild, yes, they are aware, nandi. Tano and Algini, however, remain out of contact.”

He had hoped—he had earnestly hoped they could recover those two to his staff before morning. That somehow they would have accomplished their mission and headed in. “We do as we can,” he said, and, entrusting her cup to one of the young men, Jago excused herself to go forward, back with Banichi and Cenedi and the rest of their security.

Time, then, to take what rest he could. He had never in his life been one to sleep on planes, always alert to any bump or thump in a flight, but having been waked out of his night’s sleep, he thought that with some determination he could manage. He put the footrest of the chair up and settled, at least until the sun coming through the shaded window had become a mild, pervasive light.

It was a long, anxious trip thereafter, the flight across the continental divide, and on across a sizeable expanse of wilderness.

The dowager slept through lunch. The boy slept. Bren went back into Guild territory to check on the youngster’s welfare—Jegari was resting well, injuries eased with ice, the doctor rousing him periodically to check his alertness, considering the concussion—and Bren detoured to have a look out the unshaded windows there.

Hills lay behind the wing, below them, in front of them. They were flying over an immense expanse of snowy, untamed land, a wilderness cut by rivers, but not by roads, except only one: the transcontinental rail, and they were following that course, not visible from this height and with the sunglare, but, knowing the general routes planes took, he was sure it was down there.

From the Divide, the land rolled down toward the Kadenamar, a vast river drainage, an immense fault that probably followed an old plate boundary—at least the experts had advanced that theory. In that wild, game-rich territory, still far ahead of them, the Kadena River’s ancient plateaus descended step by step to a wide and sudden lowland, a region of lakes in the north—old glaciation, the same experts said—with an expanse of boggy land to the south, a natural barrier which had held the East from the sea.

That geological fact had meant no ports, no seacoast trade. Every resource the East used was consequently bottled into a tract of habitable and rich land along the Kadena, the hills rich in minerals, the plains rich in game, the river margin rich in arable soil.

It should have been a paradise—if not for the history of equally bottled-up feuding clans, mostly situated in the lake country, above the fever-belt to the south.

And—invading that paradise—came the railroad, after the epic struggle of its builders, through tunnels and across bridges. Once across the Divide, the rail began to follow an easier route.

The greatest tributary of the Kadena, the Naijendar, started as a modest stream and a high scenic falls in the snowmelt of the Divide. It wove in other streams until it became a torrent, a whitewater flood that steadily gained volume and violence on its eastward plunge. The Naijendar had cut the route the rail followed, that, nowadays, planes followed for a guide—because civilization had followed that route, too, in the earliest regular trade between east and west, the ancient mountain trail, a precarious track rife with bandits and legends of buried treasure.

Malguri had gotten its early power by controlling that route—as the one convenient access to the mountain wealth of ore and, later, of water power and electricity. Malguri had begun as a medieval fortress perched high in the hills that overlooked the Naijendar, the lake it filled, the eventual rail-route—and now ran the modern airport that met the railhead.

In fact, planetary geology, ancient trade routes, and the hard-handedness of the ancestors had conspired to put the supreme power over Eastern politics into the hands of the latest Lord of Malguri, namely Ilisidi, grandmother of the aiji in Shejidan.

Oh, there were rival centers, dotted about the various lesser lakes and flatlands. They never had managed to get the better of their local geology, a few growing rich off trade, but that had to pass through Malguri. And the East had generally opposed the determination of the western atevi to get a railroad from coast to coast, to get that wealth of ores and game from the East to their factories and their tables. Not Malguri, whose lord had seen it would pass through his hands, going and coming.

The west, already carving its tunnel and laying track through the mountains on a collision course with Eastern culture, had started playing high-stakes politics with Ilisidi’s father.

The aiji of Shejidan had ended up not conducting a war, but marrying his way into that trade route.

The aiji in Shejidan had brought his bride west, probably hoping for her to keep enough of a claim on Malguri to prevent the East from falling apart, but never expecting her to become a force in western politics—or possibly—rumor had it—to aspire to rule the aishidi’tat. She had come damned close.

Ilisidi had been no fool, in anything. Her sojourn in the west had never loosened her real grip on Malguri—Malguri the province, not just the ancient fortress itself. Her neighbors knew who was in charge. The aiji in Shejidan had gotten a son of both bloodlines, and that son had gotten a grandson, Ilisidi’s grandson Tabini, who had yanked the southerners into the aishidi’tat. Now Ilisidi had gotten a great-grandson—who wove even more of the lineages of the aishidi’tat into his person, by bringing in the Padi Valley. And then she had gone off to space with that great-grandson, and if all the world had wondered if she or the boy would come backc the East had the greatest reason to worry.

The paidhi had seen Ilisidi’s Eastern establishment in action: he had visited that ancient heart of Ilisidi’s power, not half understanding at the time either the history or the current state of affairsc how Malguri was not only the fortress, with its handful of staff, but was the whole widespread holding, villages, towns, establishments, alliances—and control of the primary railhead and airport for the whole eastern subcontinent. He had not appreciated the commercial power and wealth that lordship over Malguri entailed. Now he did.

Not to mention the import of certain advantages out of the west into the East, like Guild support for the aiji-dowager. It was never in the interest of the Assassins’ Guild, the Messengers’ Guild, the Makers’ Guild, or the Merchants’ Guild or any other guild, for that matter, that anything should ever disrupt the hold Ilisidi had on Malguri and that Malguri had over the whole of the Eastc because she controlled the one point that kept the ore coming into the western manufacturies and held the rest of the East in check.

Damned right that the dowager’s two-year-long absence in deep space could have encouraged certain ambitious parties in the East to think that Malguri might finally be leaderless, that with Murini-aiji overthrowing Ilisidi’s grandson Tabini—the whole world might change shape. Even people who would never want to overthrow her authority might have started making precautionary alliances, when the west, for its own reasons, started going to hell in a handbasket.

Damned right that Ilisidi’s unheralded return might have caught a handful of her neighbors by surprise, some of them with potentially compromising recent histories, others vastly embarrassed to be in the company her agents might have reported they were in.

Her neighbors had come west to have dinner with her and welcome her home?

My God, how had the paidhi been so dim?

Damned sure that the aiji-dowager had not been overwhelmed by sentiment and gratitude that evening. She had had all her connections on display.

Now he waked to the currents that had been running at that table. He saw the whole pattern below them, in that thin white gash that was the Naijendar and the railroad, leading like a missile track to Malguri and all it meant to the aishidi’tat.

Stupid human. He’d been so preoccupied with the dangers in space. He’d taken Tabini’s power for unshakeable until he saw it shaken, and taken Ilisidi’s power for granted even after that example. Even Tabini, blood of her blood, had had to fight back the immediate western atevi assumption that Ilisidi herself, the mysterious Easterner, had the greatest motive to orchestrate this move, and the theft of her own great-grandson.

One could so easily think that, standing on a balcony overlooking the maze of roofs that was Shejidan, with all its convolute politics.

Looking down on the Naijendar, however—one found other perspectives that slammed western suspicions sideways.

Malguri had always played for power. It would do that now. It absolutely would. And Ilisidi’s neighbors hadn’t done what they’d done without the notion they could get something out of it and get away with it.

What? A share of power if they helped her hold the heir for ransom?

It was no more than what they had—a small range of political power for their transport-dependent little provincial centers. One could not even say capitals—provincial centers.

Provincial networks. Mines. The tradition-bound East would not even smelt the ore it mined. They were not industrial, like the west. They refused to be. They made choices that stemmed purely from the desire for raw resources, and the power to move them—or withhold them.

And they had that. If they left their province, they had nothing—nothing that they valued. So what did they want, that could let them deal with Ilisidi and make bargains?

He raked through memory, recalling what mines, what products, what raw resources the several lords shipped from their districts.

And unless there was more to the move than three lords, there was no way in hell they could arrange an embargo against the west if things went down to the trenches. Rival lords, their neighbors, would break it, and it would all fall to pieces.

More, Ilisidi could have gotten her great-grandson to the airport herself without breaking eggs, as the proverb ran. She could have snatched him off to the East with his two Taibeni attendants and used them to mollify the wrath of the Taibeni Ragi, who supported Tabini. Such a plot, with her involved, would not be running the way it had, half-assed and losing Jegari out the back of that truck.

Hell, no.

So back up. Retrace. There was no way this effort was going to win Ilisidi as an ally.

But what did the conspirators stand to gain? Overthrow Ilisidi?

Embarrass her?

That was about the most dangerous course he could think of.

Lure her East?

They were certainly doing that. If Ilisidi hadn’t been visiting Tatiseigi at Tirnamardi, the kidnapping would have– —might have involved Ilisidi as well as the heir. The plotters would have had to take on her security, or incapacitate them. They had not gone into the other wing of the apartment to take on Tabini and his guards, who were not a known quantity. They’d gotten in, and out, with some facility they shouldn’t have had, damn it.

Consider: if Ilisidi were no longer in the picture—the East fell apart, it bloody fell apart. That could have been one objective.

Chaos. And who benefitted from that? That thought led to some very bad placesc mostly in the south.

Except, if, down in that hotel, waiting their chance, the conspirators had heard through their sources that Ilisidi was leaving, and leaving behind the boy—who was heir to– Malguri itself, as it happened. Cajeiri was not only his father’s only heir—he was Ilisidi’s ultimate heir, the one who would have to succeed her—there was no other choice, since it was damned sure she was not going to cede her power to her grandson Tabini.

Damn, the boy not only united the bloodlines of the west– and stood to become aiji in Shejidan—he stood to inherit the keystone to the East, to boot.

Some of Ilisidi’s neighbors weren’t going to like that idea.

And that—God, that didn’t augur as well for the boy’s safety. If negotiations went wrong, if things started sliding amiss—it wasn’t good, was it?

Events were tumbling one after the other. They were in virtual hot pursuit, as it was. There had not been time to analyze everything. But was it possible the west—even Tabini—had been looking through the wrong end of the telescope?

He left his window, moved quietly to settle on the edge of an empty seat by Jago and Banichi.

He said: “The boy, nadiin-ji, is heir to the aishidi’tat. But from the Eastern view, he is heir to Malguri.”

“Indeed,” Banichi said.

His staff had a way of making him feel as if the truth had been blazoned in neon lights for everyone to see—and he always, always got to it late.

Still, he plowed on. “They would have wished the dowager dead, or in their hands. But whatever traitor there was on staff would have advised them she was in Tirnamardi. That left—”

For once, once, he saw a simultaneous recognition go through their eyes. It was a dire little thought they had not had. He had no idea what thought, but it evoked something.

“They would have learned that the paidhi had relocated, as well,”

Banichi said, “and that the aiji had moved in. They would have been fools to take on the aiji’s precautions. His own staff was around him.”

“While Cajeiri’s was mostly the dowager’s,” Jago said, “like the traitor herself.”

“You know specifically who it was, nadiin-ji?” Bren asked.