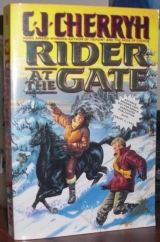

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

But it was a serious decision. It might be a spooked, unwise decision, with the sleet having turned to honest snow by the time they passed the shelter on the trail.

The shelter sat unoccupied, Tara knew that in the same way she knew the ambient and saw no smoke from the chimney. She had no doubt it was stocked and ready for winter—Chad and Vadim had escorted the teams out with the winter supplies the first leaf-turn: clean blankets, grain, preserved meat in strong, pilfer-proof tins, medicines, cordage, anything a storm-trapped rider might need.

She might be foolish. The way ahead of them was turning as white as Flicker’s frantic imaging, and there was safety in those thick log walls and those heavy shutters, if one could keep the doors barred. The shelter would hold her and Flicker both, no question.

But no shelter could help if a rider, in the grip of predator-sent illusions, chose to unbar a door or open a shutter. If you got yourself besieged indoors by a persistent predator, illusions came through walls, through shutters, through barred doors, illusions to confuse a horse and beguile a fool human into lifting a latch.

Flicker snorted and shook herself, never slacking pace as they moved on down the road. Tara agreed by doing nothing and they both committed themselves to the try for at least the next shelter, if not for home. It was a very uneasy feeling in Tara’s several looks back, as the shelter lay farther and farther behind them, as woods closed between and the storm showed signs not of abating, but of getting worse.

It might well have been a mistake, Tara thought. Not necessarily a fatal one, but a rider didn’t get too many such mistakes for free, not in a long life. Staying the night there might have been a mistake, too. She didn’t know. She had no way to judge now, either the weather or the uneasiness about the Wild that still crawled up and down her nerves.

As bad as the weather was looking now, the road crew she’d just taken out to their work might indeed be coming back, all of them, scared by the same storm—so if she’d stayed at the shelter, she might not have been alone for more than the night. If the road crew did decide to winterize the equipment and break camp, Barry and Llew would push through the night if necessary, at whatever pace they could with the ox-teams. They’d offload everything, cache even the supplies, if they didn’t like the look of the weather; and the stolid-seeming oxen could move fast, if they moved unladed, not as fast as nighthorses, but they might be headed for that shelter, all the same.

If shewere in charge instead of Barry, the way it was looking now, no question they’d chuck it and leave that exposed mountain flank before the drifts built up.

Barry, though, was a get-the-job-done man. Village-bred, not a born rider. Villagers liked to deal with him. He made sense to village-siders, and Barry had agreed with this jaunt out to flirt with the weather and been willing to sit out there freezing his fingers and toes off. Not to mention other useful parts.

A cold gust blew up the skirts of her coat, found its way into her bones, and she buttoned the weather-bands tightly around her glove cuffs, then took her hat off to get a closer fit on the scarf that protected her ears from frostbite. She slid the chin-cord tight when she put it on again, and turned her collar up. She had a knitted hood in her inside pocket. It made her face itch and she hated it.

Most of all it restricted her side vision, and she wanted to know what was around her, on the edges of her vision, even if it was misty white and the misted shapes of trees.

But,

Spooked, she said to herself. Too much thinking on disaster in this perilous season. She imaged

She imaged

But that shelter was a long ways behind them now, and the next chance lay a good distance ahead.

They knew the trail. Despite the whiteout, she was sure they hadn’t left the road. She could see the markers on the trees arriving out of oblivion and passing by in Flicker’s constant, even strides.

Possible that some new creature had moved into the woods. Humans weren’t native to these mountains—not even native to the world they lived in, the seniors said so: now and again something did show up that nobody’d seen, pushed by the storm winds, driven by fiercer predators or by some unguessable notion of prey to be had this side of the mountain divide, she didn’t know. Sometimes a wild horse would show up with an image you didn’t want to know about. Nobody claimed to have met everything there was to meet in the woods; Flicker was all the opinion she trusted now, Flicker felt something she didn’t like… void and the smell of death, that was what began to come through the ambient, something that crawled with scavengers and came out of the storm, neither dark nor light. It was everything. It was nothing at all.

But it was prickling at the edges of her attention.

Flicker jolted forward into a sudden, neck-snapping run.

Flicker slowed, breathing through her mouth in great, cold gasps—and kept making a little forward progress, just a little, a walk on a wider-open stretch of road. There was still one more shelter ahead, the last between them and the village, but Flicker’s reaction to that image, too, was a spooky, wordless no, Flicker wouldn’t stay there. Flicker kept walking, picked up speed on the downhills and trudged up the climbs, an ox-road and as level as the road-builders could make it. The place felt safer now, and if Flicker wanted to rest, Tara was for it.

But she didn’t get off, because if that sending came down again, she didn’t rely on Flicker staying sane or remembering that she was leaving her rider stranded. There was a limit, even to their long partnership, and a goblin-cat confused even a nighthorse, if that was what it was.

Hours on, well into afternoon, they came to that second shelter. Flicker’s legs and chest were spattered with ice now. Flicker’s breath huffed in great heavy pulses.

Flicker imaged only

The falling snow slowly took on a kind of dim gold haze that passed to a hint of blue, heralding night, one of those snowy, moon-up nights that might have no boundary from the day. The second shelter was no-return now. It was farther back than it was on to Tarmin, and the night was blued and pale.

Flicker wasn’t taking bribes. Flicker wasn’t listening at all. Flicker just kept going, in a fear that wasn’t at all panic, a fear that just didn’t let go, didn’t allow rest.

Until between one stride and the next… the fear dropped away from them, different than its prior comings and goings—it just all of a sudden didn’t exist, might never have existed, leaving a nighthorse running and forgetting why and a rider who never hadclearly known the cause.

Flicker slowed to a shuddery walk, snorting and blowing and slavering onto a chest spattered with ice—walked, with wobbly steps, and Tara slid down, her fears of phantoms in the dark replaced by a real and present fear of Flicker collapsing under her rider’s weight.

Flicker wasn’t sure. Flicker was confused where she was, but in that confusion she kept listening to her rider, and Tara kept walking, holding a fistful of Flicker’s mane to be sure they stayed together. She cast through the haze of snow and blued night, picking out what the markers told her was the trail, despite the trackless blanketing of snow.

She smelled the smoke of cookfires, then. She imaged

“Come on,” she muttered to the insensate wood, and hammered on it with her fist.

The spyhole opened. They were being careful tonight. An eye regarded her before someone lifted the bar.

“Need help,” she said. It was Vadim who had answered the gate-bell, and Vadim who shut the gate behind her as she led Flicker in, heading for the nighthorse den where warm bodies kept the air a constant temperature—where other horses, other minds, were solid, friendly, ordinary.

Images flashed back and forth as she met that warmth, Flicker’s

She couldn’t stop it—she couldn’t get Flicker to stop—couldn’t come out—couldn’t escape—couldn’t stop the light—

“God,” Vadim said quietly, coming into that flood of panic.

She was lost in it, trying to shut it down. She felt smothered when Vadim put his arms around her, hugged her against him–

“Tara!” Vadim shook her till her head snapped back. Till she couldsee the dark around them. He hugged her till her joints cracked, kissed her, breathed warmth on her.

“Get help.” She’d been too cold to shiver. In the still warmth of the den, in Vadim’s attempts to warm her, his sending that she couldn’t take in—she found the ability. “Water. Cold water. Need more hands.”

When you were this cold you started with cold water compresses, and you kept increasing the heat in the water little by little. If she and Flicker were alone she’d do it herself, but there was help. Chad and Luisa and Mina were in the barracks, and with a

Vadim hadn’t been where the danger was. He hadn’t felt it stalking behind him. He only had the echoes. And by that shapeless, dark fear of his, she knew how desperate it had been—still was, in her mind.

“We’re all right,” she said to Flicker, pressing close against Flicker’s shoulder, thinking

In not very long at all, her partners came running, Mina and young Luisa, all appalled, saying there was a rogue, they’d had a phone call clear from Shamesey, they’d wanted to come after her, but Vadim and Chad had held out against their going outside the walls—

Flicker just kept imaging

Chapter viii

MAN’S A DAMN GHOST,” HAWLEY SAID, AT THEIR WIND-BLOWN campfire that night, high on the road, in a clump of evergreens that gave them a little shelter. There was no sign of passage but the ruts the trucks had made in the road. The prints of horses on the dust were old, hardened mud; the tracks of game were newer. They hadn’t turned up tracks or sight or scent of Guil Stuart or, for that matter, any sight at all of whoever they’d sensed following them.

Maybe we imagined it, Danny thought against his day-long inclination. He was, by now, willing to doubt his perceptions and Cloud’s.

Maybe I misled everybody.

“It’s sure a steep climb if he’s gone straight up the ridge,” Luke said, meaning

The question turned unexpectedly to Danny then, when his mind was half-elsewhere; but Jonas was next to him, looking at him, so that a crawling-feeling went up and down Danny’s skin.

Jonas wanted, Jonas was impatient, that came through, and Danny’s wits went scattered.

“Boy,” Jonas said. “You’d tell us if you had a thought of Stuart’s whereabouts. That so?”

“Yeah, but I don’t. Sorry.”

Jonas kept pushing at him. Friendly in the morning. Jonas’ back to him all afternoon. Everybody talking. Except him.

He rolled to his knees, intending to leave the fireside and go over to Cloud’s vicinity, where he was comfortable and welcome.

“Kid,” Luke said, not half so harshly. Luke was the friendlier, youngest one, the one he didn’t want a fight with—Luke maybe knew it. He couldn’t tell what got through to other people. “Sit down. Sit down, all right? Just a question.”

It wasn’t just a question, he thought, with upset still roiling in his stomach. The question he was asking himself was about his own competency, a question so wide and general through his life he didn’t want to consider it except piece at a time, and most of all he didn’t want to consider it with them.

But he didn’t want a fight with Luke, so he sat back down, arm around one knee, and found a dead seedpod to break up into dry pieces.

“Ought to have stayed with mama,” Jonas muttered.

“Yeah, fine,” he said back. “You want an answer, Jonas, sir? I don’t know where he is. I’m not hiding him.”

“You’re being loud, kid,” Jonas said.

“Yeah, well, get off me. Doing the best I can.” He didn’t look at Jonas or the rest of them. The seedpod was far more interesting. It had four inside chambers, with hard, round seeds, brown in the firelight. Crunch. Four, six, a handful. He tossed them at the fire, one, two, three, trying to land one where it would burn visibly. Two hit, off, the third landed under the glowing archway of branches at the edge. Achievement.

“Kid.” That was Hawley. He didn’t dislike Hawley. He really, really wasn’t sure about Jonas.

“Kid’s adjusting,” Jonas said. “And he doesn’tknow.”

Truth. Jonas always talked nicer abouthim than Jonas talked tohim. He didn’t know why Jonas couldn’t do a little adjusting himself.

Didn’t know why Jonas had wanted him if nobody was going to believe him, except that remark Jonas had made about him being bait, and he didn’t take that altogether as fluffery. They might have intentions like that, using him that way, to draw Stuart in; and no reason they shouldn’t tell him so.

They probably thought he was lying about people following him, trying to make himself important, trying to cover his trailing in late the way he had, as if there was some big, awful danger out there and he’d escaped it on his own.

Serve them right if somebody did come up on them. And he’d warn them, of course, but they wouldn’t listen. They were seniors, and knew everything.

“Kid,” Jonas said. “Calm downfor two minutes, have you got it? We can send the horses off a ways so you and I can have a discussion, if you want.”

“No, sir,” he muttered. Nobody was sending Cloud anywhere he didn’t want Cloud to go. But it wasn’t smart to quarrel with men who carried knives for more than fire-making. It didn’t even take a junior’s intelligence to figure that out.

“Guns are quicker,” Jonas remarked dryly.

He was sending, again. Dammit.

“The kid’s just upset,” Luke said. “Lay off, Jonas. You’re pushing him too hard.”

“Damn right I’m pushing him. We leave himat Tarmin village first chance we get. The rogue’d have him for breakfast. Go right for him, it would. I don’t plan to get him killed.”

Madder and madder. Insult and concern. He couldn’t read Jonas’ signals and he couldn’t say whether Jonas was right or wrong. He wanted to go to Cloud the way he’d started to and not have to listen to them. He’d no need of lectures. But he’d been told to sit down, by the only one of them who was civil to him, and if Luke got mad at him the trip was going to be hell.

Cloud ambled up into the firelight, snuffing at the ground, insinuated his big head over Danny’s shoulder and rested it there, imaging

Danny patted Cloud’s cheek, and Cloud’s soft nose investigated his pockets, wanting

Cloud didn’t do things totally unselfishly.

“What I still can’t figure,” Hawley said, “is what he’s doing.”

He meant Stuart.

“Maybe he thinks the camp’s sent out hunters,” Luke said.

“They have, of course,” Jonas said, and it took Danny a second and more to realize Jonas meant themselves, that thatwas what they were. It didn’t even count whoever was following them. He told himself what he’d perceived was real, no matter what Jonas thought. It was a damned stupid mess, over a rider who hadn’t done anything– anythingbut go to the gate trying to get his belongings back.

Which they had brought with them. Supposedly to give Stuart’s belongings back to him when they found him.

But he wasn’t so sure what Jonas’ personal motives were.

He was probably sending again, but Jonas ignored it, just kicked the cook pan into the fire for the fire to clean. There wasn’t much grease. It made a flare, and the flare died quickly. He’d have to wipe it down in the morning, with a twist of grass, nasty job. But the youngest rider always got those jobs, it was a law of the universe.

“Suppose he did get hit worse than we thought?” Luke asked.

“I don’t think so,” Danny muttered without even thinking about it, and wished he hadn’t opened his mouth on any of their business, but Luke asking was different from Jonas asking, in his estimation, and by that comment, he’d committed himself. He found his hand resting on his leg above the knee, remembered the pain of the gunshot across the skin, the shock to the knee bones and tendons, vivid memory—he’d played it out a dozen times in his head and he did it for them, the whole image, to answer Luke’s question.

“Didn’t go through,” Hawley judged with a grimace. “Went past. Burned him good, knocked him down, is all.”

“Good,” Jonas said, not meaning about knocking Stuart down, meaning him: he suddenly figured he’d just done exactly what Jonas had been trying to get out of him, exactly the way that Jonas expected, and he hatedJonas for the satisfied look Jonas cast in his direction. But he held onto Cloud’s forelock long enough to distract Cloud when Cloud jerked his head up. Cloud’s hair burned through his hand. And Jonas won. Jonas was used to winning.

“Kid’s damned good when he wants to be,” Hawley said, which doubly confused him, about whether Hawley was serious or sarcastic, as Hawley, immediately off on another tangent, imaged

“Maybe not,” Luke said, not about him being good when he wanted to be: it was the rider-image Luke shook apart, in favor of < level trail >; a definite place, it seemed to be, but it could be any place. Theyknew what they were imaging. He didn’t. He sat there with places he’d never seen flying back and forth through his vision and no knowledge what the question was.

From out of nowhere Jonas put his hand on Danny’s knee– scared hell out of him, that too personal, powerful touch—shook him right out of his thoughts. “Gone across to Anveney?” Jonas asked without paying further attention to him, and the image of town and smokestacks Danny had never seen in person was certainly Anveney the way he’d seen it before, in his head. It was a place, he’d learned, that riders didn’t like, except Anveney paid well… and it was the only place of all the places in the world besides Shamesey he could have identified without their help.

Jonas hit his knee, meaning Shut up, Danny thought; stop thinking into the ambient.

“Man’s got no supplies,” Luke said.

“Question is if he’s got money,” Jonas said.

“I wouldn’t leave mystash under any hostel mattress,” Hawley said. “Not in Shamesey town.”

Insult his town, while he was at it. There were limits.

Another pat of Jonas’ unwelcome hand, and Jonas wasn’t even talking to him. Jonas was thinking about a building somewhere else, a place with bars on the windows, a jail, Danny thought at first, and then thought not, it was a business. “Has he,” Jonas asked, “got a draw on Aby’s account?”

The question surprised Hawley, angered Hawley. Danny didn’t know why. Then it seemed to perplex Hawley, who scratched his stubbled chin. “Hell. She never said.”

Jonas asked: “How much was in there?”

“Healthy amount,” Hawley said sullenly. “It’s not his.”

What did they do? Danny wondered. It sounded like an account at a bank, and money the dead rider had had there—that they thought Stuart might have gone to get.

There was an uneasiness in the air, Hawley’s Ice, Cloud, Jonas’ Shadow all suddenly on edge. Jonas wasn’t at all happy.

Hawley wasn’t.

Hawley had gotten the money the dead rider owned, out of a bank, somewhere not in Shamesey—which was maybe Anveney. Danny didn’t know about banks or how you got money out of them. He’d never been inside one. Papa kept his money on him, or in the hiding-place under the floor, which he didn’t want to think about with these men seeing it…

“Kid,” Jonas said sharply, and laid a hard hand on his knee. Shook at him.

“Sorry.” He knew he’d slipped this time, and dangerous men were close to anger with each other all around him, a long lonely way from anywhere.

“No,” Jonas said. “We’re not angry, boy. Hawley has a right to the money. He’s her kin. He evidently proved it to the bank.”

“Everybody calm down,” Luke said. “Just calm down.”

“The damn kid’s a distraction,” Hawley muttered.

“You went in there,” Jonas said, “you took that money out.”

“I had a right!”

“You could have by-damn said, Hawley!”

“I’m onthat account. Look, I’m her cousin.”

“Dammit, Hawley!”

“If you had a word you could have said it, Jonas. You knew I was going to the bank. What did you think I was going to do? I got the card. She give me the card.”

“Calm down,” Luke said. “Hawley, it’s all right. You did all right.”

“Yeah, all right,” Jonas said. “If he goes there, if he knows about the money—”

“I had a right!” Hawley said.

“You had a right,” Luke said. “There’s no question you had a right. —Danny, you want to get up and move the horses back? Do us a favor?”

“Yes, sir,” Danny said, and got up—the horses were crowding in, snappish and pushy with the argument. He gave a shove at Cloud.

He walked in among them and suddenly a queasy darkness flittered through his mind, shapes and shadows and a violence that sent him a step back, disoriented.

Another spin. Cloud and Shadow. Heels flew past him and he jumped back barely in time.

“Shadow!” Jonas shouted.

It just stopped, horses jogged past each other in abortive attack. Shadow’s teeth snapped on empty air. Cloud’s heels kicked up and managed to miss.

He was shaking.

He’d seen Shadow’s name when the fight started, that fluttering succession of treacherous shadow-shapes. It was a dreadful name– he truly didn’t mean to think in that hostile way of Jonas’ horse, but it wasn’t a name that slid easily past the nerves. He’d mistrusted that horse from the first moment he’d dealt with it, and he didn’t turn his back on it—he was scared of that horse in a way he’d never had to be scared of a horse.

And in the aftermath of the encounter he’d just had, when he recalled Shadow’s heels flying past his head, he was twice afraid. He didn’t want to think of what could have happened to him if he’d not moved fast enough or if the fight had gotten serious with him in the midst of the horses.

Which wasn’t the way to deal with horses at all. He fought his townbred nerves. He tried to separate them out, put Cloud to one side and keep the other three from snapping at each other or him, and they kept getting around him to make another sniping attack.

“Here.” Luke Westman came to help him, clapped him on the shoulder, which did nothing to help his knees, and shoved Shadow out of a not-entirely-inquisitive approach with the back of his fist—swatted Shadow hard on the rump when he didn’t retreat.

He didn’t think it a help. But Luke waved Froth away from him and came close up on Cloud.

“What’s his name?” Luke asked, meaning the inside name, the real name Cloud called himself—but he wasn’t sure that Cloud wanted Luke to know that name. Cloud was laying his ears back and wrinkling his nose as was, and he didn’t answer Luke. He just shoved at Cloud’s chest and wanted him apart from the seniors and their horses.

“Be careful of him,” Danny said. “Cloud, behave. Don’t bite.”

“He won’t bite,” Luke said, taking something from his pocket.

He held it out. Froth muscled in and got the treat. Candy. Cloud wanted it. But Ice sneaked his head in and got the next one Luke magicked out of his pocket.

But immediately Luke’s other hand was out, offering one to Cloud… < sweet, delicious sweet > was the image in the ambient, from Luke and the horses, Danny realized, and felt Cloud wanting it, inching toward it. Sugar-candy was what he’d promised Cloud for good behavior, when he hadn’t had one, and there it was, not from his hand, but from Luke’s.

Cloud’s mouth was watering,

Cloud was going to—

“Fingers!” Danny said, earliest manners-lesson Cloud had had to learn, where treats stopped and a rider’s fingers began.

But Luke had curled his hand around to hide the treat for a second, then showed it again, just halfway, teasing, did it twice, blink of an eye, had something else out of his other pocket, in his other hand, that Shadow got before Shadow created a fuss.