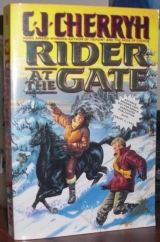

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Or you hoped you hadn’t gone too far from a truck turn-around.

With a horse—and no trucks to worry about—you rode past and hoped it didn’t get worse up above. But he had faith in Burn.

The way-shelter that was supposed to exist at sundown turned up well short of that—not that he was ahead of schedule—but that the shelter was a collection of scattered logs and scattered rags several turns below where it was supposed to be. He saw part of the foundations further up: a boulder had swept it right down the mountain face.

It left a flat camping area, once he did reach it, at the edge of night, but not one he was tempted to use. He cast a misgiving eye up at the sheer face of the mountain, wondering what other brothers those boulders had poised and waiting up there, and kept moving until dark dimmed the road too much to see.

Then he camped in a little stand of brush as sheltered from the wind as he could manage. There were spooks—he thought one was a nightbaby, by the distressing

Something evidently believed it. Whether it caught supper or whether it became supper, it went silent, and the ambient was quiet for a while.

He’d collected dead wood for some distance along the roadside before he camped, as much as he could conveniently carry—and now sheltering his little construction with his body and Burn’s, in this wide spot among the rocks where saplings clung, he built a tiny, well-protected fire, not easy when the wind searched out every nook and cranny.

So there was

Not so bad, he said to himself, snugged down dry and warm with Burn for a backrest. He had his single-action handgun resting on his lap beneath the blanket—hand on the grip but his finger prudently off the trigger, ready, if Burn heard something that Burn couldn’t scare.

He heard only nuisance spooks, all during supper.

They sang. They imaged their fierceness. He settled to sleep against something that, if Burn roused and grew annoyed, could send

Which Burn did from time to time, though not troubling to get up, when the ambient grew noisy with the nocturnal pests.

Guil sighed, imaged

Cloud hovered close, hungry and in an ill mood, but Cloud had kept that uncommon quiet, taking no chances, and imaging

He’d never known Cloud to do that before. He sometimes feared that something was wrong with Cloud’s mind; but Cloud grew disturbed when he tried to get Cloud’s attention—Cloud imaged

He didn’t know what they were going to do about food. He’d gone to sleep hungry one night, now it was the second, and he didn’t know where they were going to get food for either of them. He was mad at himself for not thinking to grab his packs, or anything– but he hadn’t been thinking at all when he’d run from the camp, and not thinking a lot today, in their forest of

They’d moved, today, and they’d seen game, but Cloud hadn’t wanted to hunt and he had no gun.

He could at least have made a fire. He had his burning-glass in his pocket, he’d some wrapped, waxed matches on him, but he was scared to do it for fear that Harper or a horse he didn’t want to meet or even think about would smell it on the wind, in this place where smells you didn’t notice downland were very, very obvious as man-made. So he’d made his bed with evergreen, the same as last night, with less desperation, with more care. And he really truly hoped Cloud would find them

But that wish got him nothing but

They’d found a berry bush with berries still left out of reach of smaller creatures, and Cloud could eat the berries, so they were probably all right, but that wasn’t always true: human beings weren’t of the same earth-stuff as horses, and you couldn’t always rely on the safety of plants horses could eat—so once he’d seen Cloud go at them, he’d tucked handfuls of the autumn-dried berries in his pockets and eaten just one of them, figuring to test if he got stomachache or went strange afterward.

He hadn’t, and they were still in his pocket, so he nibbled a few. They were sour and set his teeth on edge, but they were better than an empty stomach.

Cloud found a few sprigs of dried grass that grew about the rocks, and licked lichen or some kind of fungus off the stone; at least it looked as if Cloud was getting something to eat out of all that effort—the image was now

Which was probably smart to do, this

He watched Cloud for a while, wondering if the stuff on the rocks was edible—but he wasn’t greatly tempted to peel it off and have a try at any scummy fungus, no more than he was tempted to abandon the little warmth he’d found to go collect it.

He didn’t know where he’d go next, or, more to the point, where Cloud would be willing to take him. He was, he had to admit it to himself, lost—not lost, in not knowing where down was on the mountain, any fool could tell that, but lost because he didn’t know which side of the road he was on, and he didn’t know whether the nearest village was behind him or in front of him, above him or below him on the mountain. They hadn’t crossed a clear-cut, or seen any other indication of a road in any place they’d crossed.

Most disturbing—he figured that Cloud was imaging

Which made him, unwillingly, think about the

Cloud snorted and shied away from him, with

Because Cloud’s fool rider, having gotten them into one human mess after the other, had now lost all his gear and everything he owned. Cloud depended on his rider to see ahead and think ahead, and understand the Wild, and his fool rider hadn’t even understood human beings. He wasn’t any help to anybody, and the best thing he could do was get them off the mountain alive and get Cloud fed and safe.

<(Desire,)> came a thread of feeling. <(Bodies together, dark nighthorse bodies, feelings intense as the dark… )>

Danny caught a breath, roused out of sleep, suddenly beset by feelings he didn’t know where they’d come from—out of control, but he wouldn’t, he wouldn’t, he didn’t understand what was happening to him…

<(Wanting—wanting closeness, wanting—)>

<(… bodies merging, tearing, ripping apart—)>

<<… Watt, running through the dark, running and running– chest aching, breath coming edged with cold and terror, not enough air, branches breaking against arms and face, jabbing at eyes, branches crashing and breaking—> >

Stuart on the porch. “Stay with your horse.” Jump across time. Another moment. “Stay with your horse.” Danny and Cloud at the fireside. “Stay with your horse, whatever goes wrong, stay with your horse.”

<

Danny gasped, jerked, caught at the ground, couldn’t get breath, couldn’t overcome the falling-feeling—

<

Then could. Danny sucked in a breath, his ribs able to move.

He got another, and another, and his gloved hands knew the solid ground was under him, he hadn’t fallen. He wasn’t falling. That was somebody else—somebody was dying.

A presence went past them then, fast, like a blink of starless dark—it swirled and it reeled dizzily, it wanted, it fell, it rose, it was a man and it wasn’t—it was lost and it was angry and it was looking for someone, it lusted after sex, after touch, after feeling, after something it had <(lost and couldn’t find)>—

He suffered a spasm of chill, then of arousal, but he held himself still, too wary to catch. He felt

He thought at first it was another kind of falling, and clung to the rocks, shaking and afraid that the whole mountain would dissolve around him—straight outward into the air.

<(Hunger. Fright. Pouring through the woods—something chasing it. One and the same, predator and prey, feeding and fed upon. Pain and hunger embracing each other, tearing and biting—)>

–and shot dead.

He felt his fists knotted up. Every musle was stiff. He was dreaming, he said to himself, remembering with eyes wide awake—he didn’t know for sure it was Harper. Things you heard in the ambient sometimes didn’t come to you full blown until later, sunken things rising to the surface ofyour mind with more and more detail. He kept seeing that dead face—

He was holding evergreen bits in his hands. He was on the ground, on his evergreen bed, testing whether he could breathe on his own, and whether the ground would stay still and the rocks not fly off into the night—his brain knew better than to trust what he’d just lived, but he couldn’t let go for a long while, couldn’t understand what had just happened, until he suffered a panicked fear and found Cloud nuzzling his cheek. All right, he said to himself, all right, Danny Fisher, that was the rogue. You found it. That’s what you wanted. It’s up here. No gun. Nothing. Cloud’s got to get us out of here… A rogue could send far, far across the mountain. But if it wasn’t near them it couldn’t hear them, because sending that far, that was what itdid—but it couldn’t hear farther than theysent—and they weren’t nearly as strong or as loud. Except— Except the creatures near them. It picked that up, the same as they could, only maybe—better than they did. It had been near Watt. He’d heard—he’d beenWatt: the dark and the falling-feeling came back to him, the mind-taking pain of branches gouging an eye, tearing across his face— Harper might still be alive. Quig might. He didn’t think Watt was. Somewhere on the mountain, Stuart might be alive. Theymight get the rogue. They might shoot it. He had no gun. He sat and shook in the dark and fished a berry or two out of his pocket to take his mind off his fear. Cloud came closer to him, hungry and And suddenly he realized Cloud wasn’t stuck on the So Cloud got the berries. All he had. They weren’t much for Cloud’s big body, but Cloud got them, and Cloud’s rider had only one last one. Cloud was due that much. Cloud would find more berries tomorrow, and they’d take the chance they had and go down the mountain, please God. He’d been stupid. He’d run off from his parents and come up on the mountain where a stupid kid hadn’t any experience or any business being. God punished people like that. But maybe they had one more chance to get out of this. Cloud snorted, mad. Cloud didn’t understand God. But if that was God that was out there in the dark, Cloud took exception to his thinking about God: Cloud came between him and the wind and licked vigorously at his face, making it wet in the cold air. He tried to shove Cloud off, but Cloud wouldn’t leave him, Cloud pressed in so he had to tuck up tighter in his nook or have his face scrubbed raw. He was warm, though. He shivered, and whenever he thought– as he had to—that what he’d felt was real, and Watt had run through the woods, and Watt had fallen off the edge of some cliff—he disturbed Cloud, who didn’t want him to, and who thought about where they were and about The terror didn’t come back. Maybe the rogue was asleep. Maybe it had found what it was hunting. But he hadn’t felt it satisfied. It had just—flown away, not finished with what it was doing. –until the man was dead. He squeezed his eyes tight, not wanting to think about that. So he thought, like Cloud, about Chapter xvii THE AIR AT DAYBREAK WAS QUIET, LADEN WITH MIST THAT MADE the woolen blanket damp. Guil folded it up, wet though it was. He had two blankets. He’d felt the moisture in the air last night and not taken the other out of the pack. If the sun came out today he’d wear the one cloaklike a while and let the wind work on it; but it could only get wetter, as the morning promised to be, with a veil over the road. Today, he expected a harder trek, and maybe one more night on the climb; he hoped to God not, mistrusting the clammy mist that meant a lot of moisture in the air. It was a treacherous kind of weather. All it took was a front coming over the mountains, and they were in heavy snow—or a freezing mist. Aby had indicated in vagrant images of her high-country treks that the high end, beyond the shelter, was far steeper—more than a twenty-five percent grade in places. Ravines. Bridges. Loose fill where the roadbed was sure to have washed out at the edges. The number of trucks in the old days that had lost their brakes and taken the straight route down was legendary. With frozen sheen marking the edges of leaves this morning, it wasn’t a road to like at all—but that was the situation they had, and they walked, both of them, for an hour or more, with only hazy rock at one side to tell them where the road was bending, hazy gray at their right to tell them where empty space was, and the grade of the road and their own burning lungs and weary legs to advise them how high and fast they were climbing. At least once the sun was lighting the mist, the frost on the rocks slowly turned liquid. By midmorning a mild breeze began, and as dry cold scoured away the mist, the world below appeared in pastel miniature, a memorable view down the series of switchbacks and slides. There were fewer rock falls: a falling rock wouldn’t stayon this steep, he swore. Earth-slip had skewed a whole section of phone poles, the line not yet broken, but the poles wanted resetting. He vowed to tell Cassivey next spring in person and in no uncertain terms that if they wanted these lines to stay up, whoever was supposed to be responsible for them, they’d better hire riders—and get a road repair truck up here next summer, or not even a line-rider with a wire-cutter and a roll of tape was going to be able to get up here in another year. Damned stupid economy—to wait until they had to blast a new roadbed out. It only got worse. In one place, erosion had cut away half the road. It made him give anxious thought to the ground under their feet, which was shored up by timbers the slide had compromised. Badly. In another turn he met the first of the high bridges: the road was climbing by a rugged set of switchbacks and going further and further back into a fold of the mountain, and where the roadbuilders hadn’t found a way to blast away enough mountain to make a roadway past the slip-zone they had evidently just bridged the gap and hoped. But with the fresh scars of slides going under the bridge, he got down off Burn’s back, climbed down at least far enough on the rocks so he could take a look at the underpinnings; and it did look to be sound. He climbed up then and walked across the boards ahead of Burn—as Burn trod the weathered boards imaging It wasn’t that far down. But, give or take the missing tie-downs that made no few of the warped boards rattle and rock—and thunder like hell under wheeled traffic, Guil could well imagine—it forecast nothing good ahead. The next such bridge they reached was worse—two boards were actually missing in a span above a higher drop. Hope, Guil thought, that the villages had done better with the bridges up near the crest. Another short span. Burn had to cross over more missing boards, easy stride for a horse—but Burn was, by now, not happy with bridges in general. Then they caught sight of the big one Aby’s images had foretold they could expect, over a gorge by no means so large as Kroman, but impressive, the longest bridge yet—and as Guil looked up from below, it showed sky through its structure. Guil gazed up at it in dismay, and Burn outright balked on the gravel road, catching the image from his mind and dizzily lifting and turning his head to have his one-sided horsewise view of it. Burn immediately ducked his head down and laid his ears back, shaking his neck. Nothing to do but have a look, Guil thought, and nudged Burn with his heels, twice, to get him moving up that steep gravel incline. The bridge looked no better when they came up on a level with it, a long span over a rift in the mountain flank, a cable and timber structure far more ambitious than any they’d met. It wasn’t wholly suspension, thank God. The rails as well as the roadbed were missing pieces, and four and five of the crosslaid planks were gone at a stretch. He counted four, five such gaps in the bridge deck, so far as he could see from this side, gaps exposing the underpinnings. The boards had probably, Guil thought, sailed right off in the storms, considering the cold gusts that battered and buffeted them, sweeping unrestricted along the dry, slide-choked gorge on the one side and dizzily out into open sky and the whole of the plains and the distant haze-hidden Sea on the other. He jammed his hat on tight and slipped the cord under his chin before he walked out on the span to look it over, and the look he got sent his heart plummeting. The gaps were big enough to drop a horse through, and the winds that swept across that span could rock a man on his feet. Burn didn’t like that idea. Days– daysto go back down and across to the other route. With the weather about to turn. If he went back now he wouldn’t get up to Tarmin Ridge until spring—and that left him sitting in Anveney territory all winter, with nothing done, nothing but using up his supplies, his account—granting money was there, of which he was not entirely certain if he failed Cassivey’s commission now. If the villagers found that shipment up there in the rocks—Cassivey and a lot of Anveney folk weren’t going to be damned happy with him. He didn’t like losing, or explaining to a shipper why he’d failed; and failing what he’d promised himself and Aby, hell—it wasn’t why he’d come this far already. He walked back off the bridge. The supports were sound enough, run through with iron rods and huge metal plates bolting the whole together. He climbed back up to the road and walked out on the bridge as far as the gaps. He stood looking at the far side, then shut his eyes a moment, and made his mind as quiet and confident as he could. “Come on, Burn, dammit. It’s too far to go back.” He looked up at gray-bottomed clouds scudding above the peak. “Burn, dammit! Come on!” “Burn. Get your ass out here. < Now!>” Burn moved, came step after slow step, the wind whipping his mane upward, trying each plank, imaging as he came: “It’s all right, Burn. Come on.” Burn came up beside him, at the area of missing boards, stopped, and lowered his head to take a long, unhappy, dizzy look down into the depths below. It wasn’t easy to free one. It was a plank sized to support a small truck. It weighed like hell and he could only lever it up from the end, looking out over a sheer drop down the face of the mountain, and the wind blasted his hat off, left it spinning and jerking at his back, held only by the cord. He got the plank up, turned it, dragged it back past Burn and, with slow maneuvering and a final, satisfying thump, installed it in the gap. Burn leaned forward in curiosity and peered over that edge. Didn’t trust that board. But Burn was amazed, preoccupied with the gap, when Guil walked back by him, hand on Burn’s side. He worked and worked, freed the next plank, and dragged it along past Burn. ThenBurn caught on what he was doing, Burn backed up in a panicked rush. Guil let the plank fall crashing to the deck and grabbed a double fistful of nighthorse mane to stop him. Burn stood there shivering, with a clear imagination of the bridge unraveling behind him. “You don’t move!” He went back and got another one. Burn was still standing, shivering. Burn could cross a single missing board. Guil dragged the third board up to Burn’s position. But Burn was far from certain that any board he’d just seen moved was going to stay put. Burn grew confused about directions, and started to back up in great haste. “You fool,” Guil swore, threw himself under Burn’s rump and shoved with all the strength he had. Burn didn’t trust There were two of them shaking now. Guil retrieved the plank he’d dropped, a quarter over the edge of the decking where it had bounced. He jammed his hat back on and swore and wrestled it up to the two-plank gap. He dropped it in. He was exhausted and his headache had come back, but he wouldn’t ask Burn to accept a hand-span gap in the planks that were there—Burn’s estimation of gaps wasn’t so reliable at the moment. He dragged and wrestled with it and got it butted. Then he got up and stamped loudly over the repaired section, while Burn watched in horror. Stepped across the single missing plank. Did a kickstep across it, back and forth and twice more, like a lunatic. Then he went back to Burn, and with his hands constantly on Burn’s neck, patted and cajoled and argued, with the wind blasting up out of the gorge at both of them, rocking even Burn on his feet. He imaged When that didn’t work, he tried The last was only half a lie. It spooked Burn. Burn jumped forward, Right for the next gap. <“ Burn!”> Burn cleared it. Thump-bang!.—and stopped, scared and confused. Guil grabbed up his gear and ran, heart pounding, as far as the gap Burn had jumped, before his knees wobbled and gave out. He squatted down. Burn was standing sideways on the bridge, looking back in distress. It took a considerable while of catching his breath before Guil slung his rifle to his back, threw the two-pack across the gap, and crossed it, astride the support boards, with the wind out of the gorge blasting up under his coat and whipping his hat this way and that. Something white flew across his vision. Several more followed. Snowflakes, scattered, few, and from a partially cloudy sky. But it was a warning. It was a clear warning. “I’m trying,” Guil muttered, and tried to will the headache into some inner dark. Let his temper and the headache go off together and trade insults. They’d this bridge to cross. He didn’t know how many more. He didn’t know this road except by Aby’s image, and that was the way an experienced rider killed himself and his horse, just too damn good, too damn cocky with the weather and an unknown road a junior wouldn’t think of trying. Burn deserved better. Wasn’t going to leave Burn to freeze on a gap-toothed bridge. Two more gaps. More laborious board-movings, a twice-mashed finger, a bashed knee, a splinter through his right glove, that he couldn’t get all of with his teeth and he didn’t want to take the glove off for fear of losing it, the wind was blowing so and his fingers were so numb. Cold helped the headache, only thing he could say for it. Don’t do anything, a doctor would say—and the wind blasted at him at the worst moments of his balance, so he lost one plank that caught the wind, spun him around, and off his balance. He let go and fell, it went sailing off into the gorge: he didn’t follow it. The pistol damn near did, spun past his face to the gap: flat on his belly he grabbed that and recovered it as something else, small and shiny, slipped his pocket, skittered across the wind-scoured boards and over the edge. He’d saved the pistol, but the lighter was spook-bait. He got up and got another board. He didn’t want Burn to try another jump, even if he could talk him into it. A nighthorse walking the old timbers was one thing. A nighthorse landing on them was another. He didn’t trust the wood. But the far side hove closer and closer, plank after laboriously gained plank, and Burn crossed the next to last gap when he told Burn it was safe. “ Burn!” Guil yelled, at the same time Burn gathered himself for the charge, hoof-toed feet thundering down the board. Burn sailed across the gap, landed. A board broke—Burn went in halfway up to his hock, and Guil stared, heart stopped as Burn clambered across the last few boards to the solid bridgehead. Guil took a wobbly few steps forward, remembered his gear, gathered it up and followed, far more scared than Burn was. Burn stood on solid ground again. Burn was pleased with himself– raised a hind foot to lick a scrape, but that was all. Burn’s rider crossed the last gap above sharp rocks and mountainside and tottered to a rock-sheltered spot to sit down, dizzy, dry-mouthed with exertion, and feeling his skull trying to explode. Which wasn’t something he’d regret at the moment. But they were safe. And the smells on this side of the gorge he suddenly realized were evergreen and not chemical smoke—clean, pure evergreen, rocks, nighthorse, and the tang of snow on the wind… And Burn lipped his ear. His hands met a soft nose, velvet nudge at his cheek—Burn’s tongue licked the side of his eye with utmost delicacy and tasted salt. The taste came into Guil’s mouth, too, and identity melted. He scratched Burn’s chin where Burn liked to be scratched, he shut his eyes and saw through Burn’s,