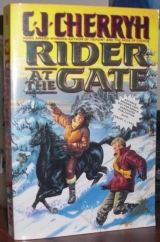

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

And with Flicker down, trying to get Flicker’s mind off it—she hadn’t had time for questions.

But she’d had to call and call for Vadim’s attention. Pound at the gate, while no one in the camp or the village was aware of the danger—God, for the same reason they wouldn’t have heard the rogue—because Flicker hadn’t relayed anything. Flicker had shut everybody near her down cold, sending

“Flicker shut us out,” she said. “You couldn’t hear it, either.”

“The thought crossed my mind,” Vadim said. “Flicker could have blocked most anything from us in the den with her. The village didn’t spook, at least—so it didn’t come closer or it was quiet except for someone listeningfor it. But there’s no point looking for tracks. The snow didn’t stop till dawn.”

That was true.

“Hell,” she said.

“If it had a rider,” Vadim said.

The whole conversation was sending chills down her nerves. She didn’t know who’d started it. Vadim was camp-boss. It was his job to find out things. He was doing that. He’d already reported to the marshal and the mayor what she’d encountered in the woods. The marshal said don’t tell the town anything: the marshal and the mayor were afraid of panic and had kept the phone call quiet. But she couldn’t fill in more detail than she’d given. “I don’t think so,” she said. “No.”

“But you never did see it. Never did even imagine seeing it.”

“I’m not one of the kids,” she said, again too sharply. She was disquieted by the thought of touching anything that wild, that unstable. It hadn’t gotten past Flicker’s determination. But a nighthorse was the most powerful thing on the planet.

A nighthorse was… far and away the most powerful thing.

“Could be one of the wild ones,” she said. “A fall, a fever.”

“And it could be anywhere in the hills,” Vadim said.

“It was here, I feltit. It was behind me. I knowwhere it was. No, it didn’t come to the gate. I was scared, was all.”

She remembered

“The wild ones will go down to lowland pastures any day now,” she said. “If there should be something with that band—maybe it’ll go down, too. Or maybe it’ll follow.”

“They’d try to drive it off. They’ll kill it if they can. They won’t let it follow them.”

She didn’t think Vadim knew any more than she did—what the wild ones might do or be able to do against a threat like that. Vadim had grown up on Rogers Peak, born to Tarmin; she’d been a free rider, but only on Darwin Peak, ranging between Darwin settlements, and they were both guessing, she knew for a fact. The long riders—they told such stories, around safe firesides. That was collectively all they knew.

“It’d go for people,” she said. “That’s what they say. I don’t know if that’s always true, but, God, if it does, there’s all the villages around the loop, besides Barry and Llew out there in that damn road camp. —Vadim, —”

“You made it in. They can make it in.”

“I was lucky!”

“You make your luck. If you heard it, they heard it, and they’ll take precautions.”

“Fine. Fine. But what if it’s smarter next time? What if the thing shows up on—”

A bell rang—the one at the village side of the Little Gate. Some villager was coming to request something of the riders, God knew what, maybe another trek out to the road crew. Maybe the marshal with worse news—maybe with a notion the weather was going to turn. She hadn’t looked at the glass since noon.

She watched as the blacksmith passed through the gate and shut it. His name was Andy Goss. His teenaged sons trailed him as he made a straight line for the porch where they stood. It sure didn’t look like a delivery.

“You seen my daughter?” the blacksmith asked, coming up out of breath.

“Not since morning,” Vadim said. And Tara remembered Brionne Goss coming into the den this morning—the kid never had understood No or Don’t or Leave my horse alone. Wonder that some horse hadn’t bitten hell out of her. Then let the father howl.

But not since morning—

“For what?” the blacksmith asked, still hard-breathing, sweating despite the cold.

“She brought a biscuit for the horses. Wanted to talk. We said it wasn’t a good time. She left.”

“Then where’d she go?” The blacksmith was angry. “We got the whole village searching, door to door. When was she here?”

The outside gate, Tara thought with a chill. The spook in the woods. The kid’s hanging about the horses… “Crack of dawn.” It was approaching twilight. “You’ve searched the village? You’ve searched all the village?”

“Everywhere.”

“Rider gate,” Tara said, and ran the steps, struck out past Goss and his sons, down across the snowy yard and toward the den, Vadim hurrying to catch up, the blacksmith and his boys close behind.

The snow between the village wall and the exposed side of the nighthorse den hadn’t melted that much during the day. They didn’t go to that side of the den unless they were going to the outside gate and nobody’d been out, none of the horses had been stirring out—truth to tell, they andthe horses had slept the whole afternoon.

But somebody in small-sized boots had gone past the corner of the den and along the wall, and not come back. The pointed-toed footprints led up to the camp’s outside gate, and the gate had been dragged open and shut again—enough, one was sure, for the owner of those boots.

“Those your daughter’s tracks?” Tara asked, indicating the prints, but the horses were near enough she was already feeling the father’s rising panic.

The father didn’t know the half of it.

“Chad and I had better go look,” Vadim said.

“The hell,” she said, imaged

“You’re not up to it,” Vadim said. “Flicker damn sure isn’t. We’ll look as far as we can follow those tracks.”

She didn’t want to stay and wait. She knew the search wasn’t going to turn up a live and happy girl, and that conviction in her mind might have been what agitated the blacksmith: they were next the den wall.

“What in hell’d she do it for?” the man asked as Vadim went off quickly around the corner,

“It was a dare,” one of the boys muttered, and an image flashed into Tara’s mind:

“Who dared her?”

But it wasn’t anywhere Tara had ever seen. And dammit, Brionne didn’thear the horses.

But she was seeing

“My girl’s been coming here?” the blacksmith cried, as if it were herfault. “She’s been in and out of here and you didn’t report it? Damn you!”

They were townsmen unused to the images that came thick and fast next the den—< Brionne with biscuits, Brionne running out the door of the den>—and Tara felt panic rising in the ambient. “She came here. I told her go home. We all told her go home. It didn’t take. She—”

She couldn’t focus on it. She was seeing

–and glared in startlement as the blacksmith for a second time caught her sleeve. < Scared. Wanting daughter.> Then images from some other near source boiled up:

God,

< Village. Gate.> Tara couldn’t find her faculty of speech. She threw force into the image, shoved at the blacksmith, wanting < Goss leaving, boys leaving. Camp gate shut.>

“Don’t you push me!” the blacksmith yelled.

Flicker’s temper hit the ambient. Flicker was on her way outside.

“Get out of here!” She found the words, scarcely the breath, and hit the man with her fist. “You’re upsetting my horse! We’ll find your daughter, man, just

She shoved him as Flicker came around the corner of the den, a shape of anger and night. It was a cul-de-sac between the den, the palisade wall and the camp’s outside gate, with a mad horse occupying the only way out, sending

“Get past!” she shouted over her shoulder, leaning all her weight and will against Flicker, making her

It was an eternity measured in breaths. Goss and his sons eased past them. Her arm shook against Flicker’s strength, Flicker’s anger—but then Goss and his sons, Goss shouting recriminations at the boys, headed back along the wall. Goss opened the Little Gate and went back to the village side of the palisade, mad, scared, with something maybe broken forever between him and his sons.

The Goss boys had let loose more truth at their father than they’d ever intended. The boys hated Brionne: the father was overwhelmed with panic and the boys with hatred of their sister. The images as they faded in distance from the wall were of rage and outrage, and a rider couldn’t judge what the right of it was, or who was justified.

Brionne was the youngest, Brionne was a pampered, headstrong brat. Given, she didn’t like the kid, but she’d never in her life shared a moment of such hatred among strangers—sendings going wild, sendings of a frankness that villagers weren’t used to, minds cycling wildly over thoughts, darting after known soft spots and old faults as unerringly as willy-wisps to ripe carrion, horse and human tempers flaring completely out of bounds.

Shaking, she leaned on Flicker’s shoulder and tried to calm Flicker down, telling herself she didn’t remotely know why Brionne had gone out this morning, or what Brionne thought she was doing—but if she had to lay a bet on it, the young fool had thought she’d heard a horse.

She didn’t like that thought. God, she didn’t like it. And she hadn’t handled Brionne’s father well. She was painfully aware she’d set up the encounter, not remotely suspecting more than concern on their side until they got near the horses.

She stood, still shuddery, with her hands on Flicker, whose mind she did understand, and kept imaging

She told herself that Flicker was still on edge from a brush with disaster; or Flicker was reacting to villager hysteria—Flicker shivered and snorted and worked her jaws,

Bound outside into danger she’d ridden through last night, for a damned spoiled brat who’d killed herself in one willful push of a latch.

Mina and Luisa arrived from around the same corner, their horses trailing behind them—but being nearer the outside wall than they were, Tara found it her job to walk along in the men’s tracks, unlatch the gate for them and fight it wide against the snow piled up inside.

“Back before dark,” Vadim said, from Quickfoot’s back, “unless we do find her trail. We might have to make a camp. I don’t think she got far.”

“She couldn’t,” she said, and clapped a hand to Vadim’s leg, trying to still the ambient. “Don’t be a fool, God, don’t either of you be fools. You know what’s out there, the damn kid’s gone to it—”

“I’ll turn him around before dark,” Chad said, meaning Vadim. “Don’t you open that gate, Tara, don’t open that gate, unless you know it’s us or it’s Barry and Llew.”

“Get back before dark!” Mina said from behind her. Vadim was Mina’s lover and hers, from time to time, as Chad was Luisa’s—or hers, from time to time, but not so often as Vadim. She caught the imaging from Mina and from Luisa, both her own most-times partners—and for a moment it was an intimacy rider with rider and horse with horse that took the breath and scared hell out of her. It was love, it was friendship,

“You’re senior,” Vadim said, and Chad’s Jumper passed by her with a whip of a well-groomed tail.

“Latch down tight,” Chad said.

Then Vadim and Chad passed the gate with a pelting of trodden snow from their horses’ heels, and rode away on a trail of young girl’s footprints.

They wouldn’t find the hope the blacksmith wanted to find, she was well sure of that.

Worse, the first hint of sunset color was already in the sky: light didn’t last long in autumn, on this eastern face of the mountains– they had a treacherously short while they could ride, to find what an uncompromising Wild might have left of Brionne Goss, and to get back again safely.

She dragged the gate shut. Mina helped. Luisa dropped the latch and shoved it down hard, to be sure.

And when, as they rounded a bend of the road around a long hill, Guil saw the rider-stone with his eyes, not his mind—he rubbed them to be sure.

Indeed the image, wrapped in the murk of rain and twilight, did stop when he pressed his fingers against his eyes.

Burn was right. There was no pasturage worth considering. The stone stood in a widening mud-puddle filling a slight depression– a sight that afflicted Guil with a shiver of some kind, be it chill of weather or doubt of the future he’d bargained for, listening to Cassivey, committing himself to the man’s employ.

Anveney was death. He didn’t know how he could have forgotten it, talking to the rich man, taking his hire. It didn’t matter if Cassivey was affable and convenient and talked an extravagantly good deal—Anveney was still death.

And when they reached the stone and he chanced to glance at the signs scratched on it, old marks and new—the first thing his eye fell on was a plain circle with a crescent.

Aby and Moon.

But Burn thought,

Something small skittered past Burn’s feet, out into the rain. Burn stamped at it, imaging

All the same, the jolt of that move hit Guil’s nerves and sent him light-headed. He had to lean on Burn’s neck until he could muster the strength to slide off under the weight of the rifle and pistol and the rest that he carried.

He committed himself finally, leaned and swung. His feet hit the ground at the same moment he shed the rifle strap into his hand. He stood very precariously for a moment, sight and hearing fading.

Then he saw and heard the rain falling in a night-lit curtain outside—felt random drops dripping through the absolute black of the chinked logs onto their heads, and breathed the mist gusted in from the open side, but the air inside the shelter felt breathlessly warm and strange to his cold-numbed skin, all the same, after the rush of wind-borne water outside.

He dragged the pack down from Burn’s shoulders and wobbled over to the wall, wet below the knees and around the cuffs of the sleeves. He couldn’t just sit down and wait to dry out, when rain could easily turn to sleet or snow and temperatures could drop below freezing with no more warning than that mountain wind out there already gave him.

He felt along the wall and leaned the rifle in the corner, then dropped the pack in what he hoped was a reasonably dry spot. Then he unbuckled and shed the weight of the sidearm to pegs he felt, some rider’s thoughtful addition to the accommodation.

Lastly, light-headed, he sat down on the damp earthen floor on the spot to strip off the wet boots and the trousers, wrapped himself below the waist in a dry blanket from the canvas pack, still wearing sweater, coat, slicker and all, because the plastic was holding in his body heat and he needed everything he had that was remotely dry to keep that heat around him.

He knew one thing for dead certain: he wasn’t moving on in the morning. If a man got soaked at the edge of winter, a man already possibly concussed, to judge by the hellish headache he carried behind his eyes, then that man if he wasn’t a total fool didn’t travel out of shelter till fire or sun had dried his clothes.

And Burn’s better night vision, in the black inside of the shelter, told him that a fire wasn’t an option. He sent Burn out into the rain,

Nobody’d restocked the shelter. Wood wasn’t available in the land any longer.

No wood. Aby’d been the culprit, maybe Hawley and Jonas. Couldn’t blame them, damn their lazy hides. But if it had been woodless when they used it they’d sure not ridden after any, either. He’dhave restocked the damn shelter unless there was a life-and-death hurry about getting out, and he didn’t think there had been. If it were anybody but Aby he’d have said careless.

But maybe with the weather changing, and a need to go on a schedule that couldn’t, by Cassivey’s whim, and needn’t, by Aby’s judgment, wait for spring—he could forgive her.

Still, —damn—

He began to shiver. He huddled there shaking his teeth out, took his hat off, put the blanket over his wet hair, wrapped his arms about himself under the blanket and slicker and tucked his feet up—he couldn’t feel his toes, but he didn’t think he’d been out there long enough for frostbite, thanks to Burn, all thanks to Burn.

Burn lapped it up like cream; and Burn began to think of

So Burn thought of

Well, so the one of them with fingers bestirred himself, teeth chattering, and, for a peace offering, took some beef jerky out of the pack, only then and shakily remembering that food hadn’t crossed his path at all today, either.

So it wasn’t bacon, and it couldn’t be bacon until the rain stopped, until he dried off, or unless a woodpile miraculously appeared, but Burn took the jerky as the best he could do under difficult circumstances, and simply thought

Burn was, overall, mollified.

Guil cut his thumb, he was shivering so, but, hell, there were worse fates. He had something to keep his stomach quiet, he was reasonably sure after a few bites that the food was going to stay down, which he hadn’t been sure of when the first bite went past his teeth, and his situation tonight, give or take the blinding headache and a slight nausea, was improving. He gave Burn less than Burn wanted, of course, but then, Burn was bottomless, and the supplies had to last a lot farther than Anveney Stone.

But he didn’t want to think where they were going first, or why, or searching for what. He shied away from that.

He thought of

Except freezing to death in a rainstorm. He was saner than that. He’d not acted like it, spooking out, out there, but Burn had known he wasn’t rational, and Burn had duly taken him where he had to go.

So I’m here, woman, he thought in distress. What more do you want?

God, I should have heard you. Should have heard, when you said you couldn’t say your reasons.

It wasn’t easy to hold back with the horses involved. They’d met as juniors, they’d been naive, having no idea how to deal with people, how much to give away, how much to deal for—at least he, personally and sometimes painfully, had had to discover the rules.

He’d run whenever she came too close to him, he’d stayed whenever it looked comfortable. He was ashamed of it—but he was a skittish sort. He just didn’t know how to tell right and wrong even with her, let alone with riders he didn’t know, least of all with townsmen; and he supposed now in hindsight that he’d sensed for four years that Aby had something going in the Anveney business. When she’d been snowed in up on the heights last year—he’d wintered down in Shamesey alone; hell, he’d been mad, Aby’d tried to talk to him—he hadn’t seen it. He just hadn’t seen it.

Maybe she’d thought he was cleverer than he was. She always gave him too much credit. And she’d gone off this summer more than mad—she’d gone off hurt.

Burn, half-asleep, jerked his head up, shifted a foreleg, licked his face once, twice, urgently, until he elbowed Burn off.

Burn always had had a jealous, protective streak.

Burn had, he recalled of a sudden, interrupted him and Aby on their first night together, at a very personal moment.

He’d been a kid, embarrassed at his horse’s manners and mad as hell. Aby’d been helpless with laughter—able to laugh, when he couldn’t find it in him.

Aby’d ever after stood between him and quarrels he’d otherwise have had. Aby could generally calm him down. Guil, she’d say, you’re being a fool. And, Down, Guil. You’re wrong. You’re outright wrong. Listen to me.

Suddenly it was that year again, that giddy, all-or-nothing time, the moment, the night, the place, an open-air camp in early autumn, with the chance of frost. Two fool kids had started out in all good behavior trying to keep warm, they’d built a small fire under a cliff, on rock that turned out to be less than comfortable. They’d shared a blanket, chastely watching leaves from quakesilvers higher up the slope drift down into their fire and go in a puff of fire. You could see the veins in fire before they went to ash—quakesilvers were tough.

He’d said it was like seeing through the leaves. She’d always remember the image, because she thought it wonderful; veins of fire in a leaf gone invisible. It was their secret. It was the image she’d cast him… whenever she wanted him.

The horses had set at their own lovemaking, autumn being wild in the air—and two chaste fools had gotten, well… warmer under their blanket, and more reckless.

And at the worst—or best—moment Burn had just gotten curious and hung his nose over them to watch.

God. He’d chased Burn clear across that mountainside, swearing and bare-ass naked and embarrassed as hell—while Aby had rolled on the ground laughing and laughing.

Two fool kids, in a place and a raw edge of weather no little dangerous. But they’d been only kids, and invulnerable, and they’d had Burn and Moon with them for protection—what forethought did they possibly need?

First love. Never faded.

He dreamed awake: he drifted in that time, before quarrels, before mistrust or a promise ever passed between them.

In the mating season, when desires ran high and thinking was at an ebb.

The rain drizzled down, dripped miserably off the firelit evergreens, and the smoke of the campfire collected under the branches, whipped this way and that by mist-laden winds, stinging eyes and noses. They sat in slickers, black and brown, glistening with rain and firelight. Drips from the overhanging boughs scored on Danny’s neck no matter how he shifted his position at the fire, and Cloud sulked, standing off from the Hallanslake horses’ position under the trees.

Hallanslakers, it turned out, felt perfectly free to get into somebody else’s supplies, saying they’d pooled everything.

Which meant they were common thieves, in Danny Fisher’s thinking, and his displeasure had to come through to them—if Cloud’s continual sulking didn’t smother it.

Nothing like his contempt seemed to bother the Hallanslakers, who were evidently used to being thought badly of.

And that left not a damn lot a sixteen-year-old could do, his gun and ammunition having been pooled, too, along with items of his personal gear he was sure he wouldn’t get back until he could physically beat the man who’d taken them, not a likely prospect, counting the man bulked like a bear.

Danny thought so too. He wasn’t even sure they were going to feed him once they’d made supper with his supplies. He and they hadn’t been at all pleasant with each other.

But when they got down to handing it out, he set his jaw, got up and made his move for what he figured was a fair share. Nobody stopped him from filling his plate.

He ate a spoonful. Hewas a better cook than that. He didn’t care who heard the thought.

He had his biscuits and sausage—or half of it. He saved half for Cloud, who otherwise was making do on the sparse, edge-of-the-road grass pasture, in the dark and the rain. The Hallanslakers took shares out to their own horses, which was at least decent behavior; Danny slipped Cloud a biscuit and half of the sausage.

The other horses thought they were going to push in for Cloud’s dinner. Danny took his life in his hands and swatted one nighthorse nose that came far too close—dodged a kick and bumped into one of the Hallanslakers, Watt, who grabbed him, sent a surly

“Then keep him out of my horse’s face,” he answered Watt back, in the same mood he’d swatted the horse.

And got spun around by another hand, face-to-face with Ancel Harper.

“I’m not going to stand there and get bit!” he said to Harper.

“You…” Harper said, “be careful how you carry yourself, kid. You could have a serious accident.”

The man meant it. Danny had no doubt. Cloud meant the anger hesent, too.