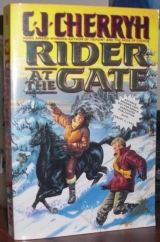

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“You’ll spook him,” Danny said, imaging

“Why’s he scared?” Randy was upset. “I didn’t do anything.”

“They’re like that. You want him. He doesn’t like that.”

“That’s stupid,” Randy said.

“No, it isn’t,” Carlo said, out of breath. “He’s got his own ideas. You do what the man says, brat. You be polite.”

“To the horse?”

“Damned right,” Danny said.

Randy thought about it. He thought about

Randy did a lot of thinking after that. The air grew cluttered with it.

But up ahead Jonas’ group had finally gone to walking, and they were catching up slowly. “We better close it up,” Danny said, because he wasn’t entirely easy with the gap they’d let develop. The boys were gasping with the effort they were already making; they looked at him as if he’d asked them to fly. But he got down and took Carlo’s pack and Randy’s, and that made a difference, the three of them slogging along in the track the horses had already broken through the knee-high snow.

Then to their vast relief Jonas pulled a full stop and waited—the only grace they’d gotten from Jonas since they’d started out.

And by the time they did catch up, Jonas and the rest had broken out food for them and for the horses—having breakfast standing, because there wasn’t a warm place to sit except on horseback. Besides snow for water, they had a bottle of vodka to pass around, the only thing that wasn’t frozen: the sandwiches were, and took effort.

But the borderers had known better than they had and kept one sandwich inside their coats—flattened, but not frozen; and they learned.

“You stay tighter,” Jonas said to him, when he borrowed the bottle. “You’re cat-bait back there.”

“I’m trying,” he said. “I know we’re pushing hard, but those kids—”

<“Come here,”> Jonas said, led him up past the horses and pointed at their feet.

Horse track. He looked off down the clear-cut, and far as he could see, there was an unmistakable disturbance, a track clearly made since the snow had stopped last night, on ground not yet churned up by their own horses. They’d been riding down that trail and he, lagging back, hadn’t even seen it.

It might be the rogue. It might be Harper. It might even be Stuart. The trail was clearly going Stuart’s direction, and moving ahead of them.

He’d been going along dealing with the boys. He could have ridden right into ambush. He looked in the direction the trail led, down the clear-cut of the road, mountain on one side and a forested drop on the other.

“There’s a shelter halfway to the junction,” Jonas said. “Stuart’s got no reason not to stay there. He doesn’t know Harper’s after him. But Harper can figure where to find him. We’re going to have to make time.”

“Yeah,” Danny said. “Quig with him?”

He didn’t know about Quig. What he saw underfoot was one track. There was no second rider, no second horse. Maybe he hadhit someone when he fired.

“If Quig’s got sense,” Jonas said, “he folded last night and got the hell to cover. Depends on how much he likes Harper. Or how much he hates Stuart. That’s only Harper going this direction. Nobody else.”

It was a clear, glaring bright morning. Burn and Flicker, let loose from the shelter, went immediately to roll in the snow, working the kinks out of building-cramped nighthorse backs and looking the total fools. Burn turned silly and luxurious, not a care in the world, wallowed upside down, feet tucked, belly to the morning sun, then righted himself and surged to his feet for a few running kicks.

They came back to the snow-door with snow caked to their hides and knotted in their manes—Burn had a great lump of ice started in his mane, where warm horse had met new snow. Flicker was starting a number of snowballs in her tail.

“God,” Guil sighed, and went in and bolted the snow-door shut, the last thing of all before they went out the main door and left the latch-cord out.

They started out walking, he and Tara, the horses free to work their sore spots out—and break the way for them unencumbered, through an area drifted deep across the clear-cut of the road. The horses threw snow with abandon, kicked and plunged their way through the drift like yearlings.

They called the horses back after not too long, anxious for the hazards of the area. And Burn and Flicker came back to walk with them, sulking at first, but happier when they understood

The skittishness of the season still had Burn and the mare flighty and spooked—Guil hoped that was all they were reacting to. And there seemed nothing more sinister than lust in the air when they finally coaxed the rascals to take them up to ride for the next while: a silly, giddy heat that made two humans feel awkward with each other in the memory of last night.

Guil at least felt awkward this morning—asking himself ever since they waked what he’d done and what he’d been thinking of, and where he’d lost his common sense in the blankets last night.

He hoped it had been Tara’s idea. He hoped he hadn’t dragged her into anything she didn’t want; but he couldn’t sort his thoughts from hers, the ambient was so confused and full of foolish horses this morning, who’d no damn thought of any serious business two minutes running. Autumn heat was no foundation to build on. You wished each other well, you vowed most times you’d not do that again—you rode off in the morning or stayed a few days as the mood took you or the weather required, and if need be that you stayed together a while longer than that, you didn’t take it for anything permanent.

You didn’t, after a night in the blankets, try to work together as if you’d known each other in any reasonable way or as if you’d any clear idea what your cabin-mate’s abilities were, or her capabilities, or her strengths and weak spots.

And it wasn’t—perhaps—that dizzy-brained a pair-up they’d almost formed. He began to believe that was a part of the disturbance he was feeling. They were out on the trail together, they were on business as serious to them separately as it was desperately vital to villages up on the High Loop. He felt the determination in the woman, a spooky, dead-earnest concentration interspersed with skittishness directed at him, and he didn’t know why. They got up on horseback and rode for a time on a level part of the road, and he kept feeling it tugging at his attention—doubt of him, anxiety– he wasn’t sure.

Both of them were facing as nasty a hunt as they’d made in their lives, they had two horses in desperate lust, and, worse, the rogue was a mare: Tara believed it and he had no reason to doubt. Much better a male that would provoke Burn to anger and defense. One more female– thatwas no natural enemy. God, lust was all over the ambient, and they were risking their necks, all of them were—only they hadn’t their enamored horses’ attention to get it through their skulls, and he couldn’t tell whether the

He’d have been terrified if he hadn’t, along with that feeling running down Burn’s spine and up his own, been sensing the levelheadedness in the woman beside him, a common sense for which he was entirely grateful—and it was no autumn lust that conjured that feeling of companionship. This woman, however skittish toward him, wasn’t going to fold on him in the hunt; she was no town rider and might be a damned good backup in a pinch—her attention patterns to the road and the brush and the hillside weren’t the patterns of a townbred rider or a scatter-wit and he knew in what he’d learned the fast way, in the ambient, that she hadn’t any intention of spooking out on him. She’d nearly lost herself to the rogue at Tarmin, but she’d had no damn help from her partners.

More to the point—she was alive after a night with no gun and no supplies in a winter storm—and in her mind was a grief and a certainty that her partners weren’t.

And on the mundanely practical side—without a word of her intentions, or any need to do anything but laze in the blankets until he had the door clear, there being only one shovel in the shelter– he’d found when he’d finished his own job that the woman had their packs put together and a dozen flatcakes cooked, so when they’d set out onto the road, they had decent food in their packs that didn’t use emergency supplies.

She’d also asked for a pocket-full of shells for the pistol—so, she said, if he lent it to her in a hurry she had a reload without needing the belt.

This was no stupid woman. He decided he’d have liked her immensely if they’d met on a trail or a camp commons or, one had to think of it, in Aby’s company: someone Aby had dealt with came with recommendations, so far as he was concerned.

More, the business about the shells had made him ashamed of his reserve of all the weapons, and he hadn’t just given her the shells; he’d given her the pistol outright, belt and all, hers with no debt, in the hope she was going to be at his back—because with her to back him up, with her knowing the territory as she did, he wasn’t obliged to stay and wait for Jonas’ doubtful help.

Possibly his skittishness toward Jonas was autumn-thinking, too. Burn and Shadow were a bad pair. And with

He and the woman, on the other hand, could be as noisy as they wanted to be, since they were looking for trouble. They didn’t, either of them, they well agreed, want to spend another night waiting for the rogue on its terms, they were reasonably sure it wasn’t behind them, and they meant to push on up the road, the only sane way up the mountain, until they attracted its attention.

They could agree on that. But it didn’t mean he’d know the rest of her signals: working with a stranger, sensible as she was, meant they couldn’t predict each other’s moves if the ambient went as crazy on them as he was afraid it would.

Another reason she needed one of the guns.

It was likely she had her own doubts about him. She was mostly thinking about her partners, with that skittish, spooky skipping-about of thoughts she had—or Flicker had. Hard to pin down. Hard to understand, sometimes. Skittish as Shadow, and that was going some. But bright, not dark; she blinded you with sunglare when you came too close to her. She whited out your vision.

And he wanted—

Hell, he didn’t know. Flicker’s change-abouts were contagious. Confusing.

Just—Aby was dead. And he wasn’t. He’d discovered that unsettling fact last night, felt guilty, and angry, and distracted, and glad—none of which he could afford right now.

Autumn promises. He neededhis mind on present business. He needed his mind on the ambient, not pouring problems into it.

So he wantedthe rogue to show, dammit—he saw no reason for them to freeze chasing it. He

“Tell you something,” Tara said to him then, in that moment that the air was still a little spooky and strange. “I was through this stretch of woods a few days ago with the rogue on my tail. I didn’t know what it was at the time—but it’s hard to be back here and not think about it. Sorry if I do it. Just so you know. It’s a memory.”

“Yeah,” he said. He’d just had a momentary sending, just

He’d provoked it, he thought.

Begging trouble. With a shell in the chamber. Driving his partner crazy. Making her doubt what she heard and saw. A help. A real help, he was being.

A kid who, if she hadn’t frozen to death, might not be sane.

Or might not want to be sane, if they did get her back.

“Kid opened a gate,” Tara said sharply. “She went out where she knew she wasn’t supposed to go.”

“Not the only village kid who ever did it,” Guil said. Her anger with the girl bothered him. There wasn’t compassion. Maybe it was because it was a girl, and Tara made demands she’d have made of herself. He didn’t know.

It was her village that was dead. It was her partners that were dead, the way Aby had been his. Her dead—her whole village, old people, kids and all—were because a kid who knew the rules had wanted what she wanted and to hell with the consequences. She was angry. And he couldn’t argue with it.

It would have been a beautiful sight, all that untracked snow, blanketed thick around the trees, the rider shelter snowed-under up to its roof on the side; but the door was all shoveled out, there was no smoke from the chimney; and the single track of a horse went right up to that area, and lost itself in the general churning up of the snow, where at least one horse had broken through the drifts.

It wasn’t what they hoped they’d find: they’d arrived too late to catch Stuart.

“ Thirdset of tracks,” Luke said in apparent surprise. “Somebody was with him.”

Harper, Danny thought, was following. But when he caught the

Harper was Spook’s rider. But—Quig? he asked himself. Quig’s horse wasn’t a mare.

The rogue was.

“Suppose the first is the rogue?” Hawley asked. “Suppose Stuart went after it this morning? Or it’s after him?”

“Check the board,” Jonas said, basic common sense, and Luke went and pulled the latch-cord, carrying his gun, even though the horses imaged no other presence, and warily checked inside.

Luke shut the door again. “Stuart. And Tara Chang, of all people.”

“ Tara’salive!” Randy said,

“That son of a bitch was real comfortable last night, wasn’t he? Didn’t wait till Aby was a month gone.”

That made Carlo

Danny swung up, nudged Cloud with knee and heel until he caught up with Shadow, on the edge of the road, urgent with the only answer he saw. “Harper’s out to kill Stuart,” he said to Jonas, fast, because horses were moving. “That’s all he wants. He knows who he’s tracking now—he’ll have seen that board, too. He’s going to break his neck getting caught up and they’re not hurrying– they’re not going to know he’s stalking them.”

Jonas didn’t take to orders. Or suggestions. You never told him a thing and expected him to do it—for sheer stubbornness, if nothing else.

“Stuart’s your friend, isn’t he?” he flung at Jonas. “Isn’t hewhy you came?”

But Jonas gave a jerk of his head, said, <“Come on,”> to his partners, and hit a traveling pace, hard and fast, with

“Where are they going?” Carlo asked, panting, as he reached Cloud’s side. “Danny?”

“Just stay with me.” God, he wanted

Cloud was exploding with the instinct to stay up with the rest, Cloud wanted

Cloud wanted—something that shivered in the air. There was everywhere the

But catching Stuart and Chang wasn’t the job they had. It was doing what riders generally did, getting villagers safely from one point to the other. Getting Carlo and Randy somewhere they wouldn’t die.

Right now he wasn’t sure where that was—whether to drop back altogether and lock themselves into the shelter, or to go on where he wasn’t damned much use.

“They’re going to shoot Brionne,” Randy said, distressed, wanting to go faster. But a human body couldn’t. They’d been going since before dawn and they couldn’t go any faster, try as they would. “Tara wouldn’t. —But they might.”

“Stuart won’t shoot any kid,” he said. He believed that, the way he’d judged Stuart from the start. “He’ll get the rogue. It’s just—”

“Harper?” Carlo panted, struggling to stay with him, while he fought Cloud’s tendency to pick the pace up. Because he was moving, Carlo and Randy with him; he didn’tknow about Harper. He didn’t trust Jonas. He didn’t like that

But not—he was convinced—not to the exclusion of other motives. There was something besides what Jonas had said was his reason.

He couldn’t leave the boys. He couldn’t go faster. But they were three guns if they weren’t too late to matter; and they were witnesses if witnesses were any restraint to Jonas Westman, whatever the man was about.

They’d passed the small cut-off that Tara said led off toward the main road, on the downhill; and they were traveling an uphill now, a place where the wind had scoured the ground all but clear of snow despite the trees. Brush held drifts. But stone showed through on the roadway.

The horses had settled out of some of their foolishness—were breathing hard on the climb, at work again after the day cooped up close indoors, and beginning to think of thirst, snatching a lick at the snow as they moved.

And human minds had settled into businesslike purpose. Guil knew he’d bothered Tara—and he’d not pushed at her personal borders, not on a morning when reason wasn’t working and the horses were doing their own pushing at each other. He felt under him the give and take of a body as entirely distracted as he was, as dangerously astray from their business as he was. He found himself gazing off up the mountain, where nothing was but snow and rock.

Not helpful, in a landscape where they weren’t seeing the animal traces they were accustomed to see. Possibly something was laired up there. He didn’t think it was a horse—not up in that tumbled rock.

Burn gave a surly kick in his stride, thinking about

He thumped Burn in the ribs, and Burn flattened his ears, threw off

“No tracks,” Tara said, watching the snow they alone were scarring.

“Noticed that.” No animals. No life stirring across or down this road.

“We’re not that far from the shelter,” Tara said. “It’s right around here.”

“Last one, isn’t it?”

“Only place left she could hole up, only chance that kid’s alive.”

“If that’s a wild horse—indoors isn’t real likely.”

“Yeah,” Tara said.

And was thinking thoughts of horse-shooting that sobered Flicker and Burn.

So was he thinking those thoughts, carrying the rifle balanced on his leg, hoping he’d see it or hear it at a distance and not—not close up in the trees; hoping he could get a clear shot at it in the woods; hoping he could get a bead on it and not hit the kid.

Tell that to the gate-guards at Shamesey, who’d missed a charging nighthorse much closer to them and hit him—Burn having that clever trick of imaging

If it was a wild one gone bad, it might not know about guns.

But what had happened at Tarmin said the gate-guards hadn’t had any luck aiming at it.

Maybe, he thought—one of those cold second thoughts that came only when they were past the point to do anything about it– maybe he shouldhave waited for Jonas to show up.

Maybe he could have ridden side by side with Jonas and Hawley without wanting to beat hell out of them. Five were a lot stronger than two, if it came to an argument of sendings.

If their two sets of horses didn’t go for each other instead of the rogue, and this morning it wasn’t certain.

If he could only figure why that gunshot, or what Jonas was doing up here at such effort.

Jonas hadn’t expected him to go to Anveney first. Hadn’t expected him to talk to Cassivey. Yeah, Guil, go on up there, get that son of a bitch horse. Make the woods safe.

We’ll just come up a few days late—

< Coming apart.>

“Sorry,” Tara said. Her breath was shaky for a moment.

“Yeah, don’t blame you. Easy. I’m not hearing anything but you.”

“Vadim kept asking me—how close it got to me in the woods.—And I don’t know. He thought—not at all.” Her teeth were all but chattering. “I couldn’t judge.”

“He was wrong.”

“The thing was so damn loud—and it called that kid right out of the village without a one of us hearing. Granted Flicker was noisy—she was screening it out; I know now why she was as loud as she was all night. It was outthere. But we didn’t hear.”

“When the kid went?”

“Her house was across the village. Closer to the other wall, that’s all I can think.” She built the village for him in the ambient; a row of houses, a single street, a rider camp protecting the one side, but only distance from the wall protecting the far side of that single street. And there were times, Guil thought, when distance wasn’t enough.

“Damn kid claimed she heard the horses better than we did– but she couldn’t hear Flicker about to back over her.”

The whole business flowed past his vision, the frustration, the bitter anger.

He couldn’t follow all of it, it went by so fast.

Tara held it back then. The evergreens were around them again. The sun was shining. Tara said,

“It’s my fault, you understand me? You can tell me all the reasons in the world. You can even tell me I was right, throwing the kid out of camp that morning.”

“That’s not what you’re saying inside.”

“No. It isn’t. But I don’t do everything I think of.”

It wasn’t at all a pleasant thought. But a kid wasn’t innocent in the ambient. Just not as strong.

Usually.

He wasn’t getting her back. There was only

For a moment the ambient stifled breath. Then Tara backed off the anger, drove it down to quiet, quiet, quiet.

“We do what we can,” Guil said. He wasn’t good with words. He sent

She’d heard her village die. He’d not been on the mountain yet, the only way he could figure it. He didn’t know how she’d stood it.

“Her damn choice,” Tara muttered finally, no weakening of her anger, just better control.

He rode thinking about that for a while, thinking he shouldn’t have given her the gun.

“Don’t do any heroics,” he said. “My rifle may be able to take it—drop the horse and miss the kid. If the kid survives—best we can do.”

Not damn easy, if it came at you—and it might, out of the trees at any moment. Aim low and hope you knew where the horse—

A chill went through the ambient, as if a cloud had gone over the sun. He looked left; and Burn pricked his ears up and laid them flat again.

The lump of snow among the trees—wasn’t a lump of snow. It was a roof, blown partially clear.

Burn was smelling

Smelled it all the way to the shelter.

The door was clear. It had been opened. But there was nothing there. The place felt empty. There were tracks in the snow, both horse and rider—pointed-toed boots. Village boots. Drag of something in the snow, he wasn’t sure what.

The place was a wreck. Pans on the floor, bed stripped, pottery broken. The place smelled of horse, smoke, burned food. Recent. The front of the mantel was smoked.

The kid hadn’t known to open the flue. Or hadn’t thought of it until she had a cabin full of smoke.

There were charred bones on the hearth. Small animal. He was almost certain—it was a small animal.

He shut the door fast, figuring Tara had seen what he’d seen, smell and filth and all.

Flicker shied from him. Burn was taking in scents, nostrils flared. The whole place reeked to their senses:

He grabbed Burn’s mane, got up, and Burn wanted to go back, turned his head downhill. Burn was agitated, thinking

Then Burn would go.

“Damn fool,” Guil muttered. Burn had almost thrown him on that last fit. He’d slid far enough he’d thought he was going off into a thicket. He gave Burn a thump behind the ribs, wanted

Where he imagined the truck had gone off.

Tara straightened his road a small distance and thinned the trees and showed him the mountainside in her memory: a steep, badly slipped face of the mountain, a road crawling up a long, long curve that was a steep ascent and a hellish downhill, with all the mountain range spread out to see.