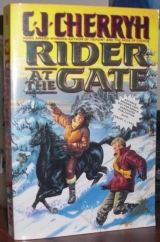

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

You only needed to be wrong once. And nobody could have predicted what had happened.

But damn the discussion they’d had at mid-summer, a discussion that had drifted to the dancing and the music and the electric lights of Shamesey camp. Sheliked it. She’d gotten snowed in last winter and left him stranded in Shamesey. She’d wanted him to come back north two winters running to the damn town, which was smoky, overcrowded, with an ambient that never let you rest. She called it excitement. He called it enough to give you a headache. He’d been stuck there lastlonely winter waiting for her while she was snowed in.

But she wanted it. Wanted—

His rebel mind suddenly, as it would, conjured corpses.

And worse, worse, the feeling, the going-apart, the lost, dreadful disintegration that occupied that place high on the road, where the evergreens came close to the unstable ground of that bad turn, and the outward view was empty air.

He shook. He pressed his hand against his eyes, blotting out the light around him. He remembered Aby living, Aby on Moon, blithe and beautiful, coming down the road in the safe lowlands.

Burn shivered under him, ripple of skin up his shoulders. Whuff of confusion.

He confused Burn, and Burn dragged him back to what was. Burn couldn’t help it—and he couldn’t. He’d dragged Burn into thinking Aby might be waiting there, when Burn knew Aby was dead, and what was Burn to think?

That was one difference between horse-mind and human: once Burn had realized death, regretted it, disposed of the matter, Burn wouldn’t go raking it over and over at the turn of a breeze. And where did what-wasn’t-real lead a horse or a rider, anyway?

He had to get the thing that had killed Aby. Hadto get it. It didn’t know any better than it did, its story was probably as sad as Aby’s, but it had destroyed Aby’s life and gotten a piece of his he couldn’t get back from it until he settled the question. For hours at a time he’d be all right, and then for a few minutes confusion would close in on him so he couldn’t breathe, and he’d lose his thoughts between past and present in a way Burn couldn’t handle.

And, equally confused, once in an hour he might think, To hell with it, ride south and forget it. You can’t bring back the dead. Aby won most times; she didn’t, once; she lost, is all. Fall of the dice. The riders up at Tarmin can handle their own trouble.

Then something would nag him saying, But all those people up there—riders not necessarily aware what’s moved in, unless the thing’s gotten noisier in the ambient. More deaths, after it got away with Aby’s.

And the way he understood the affliction, rogues didn’t alwaysmake a lot of noise. Some were very quiet. Very canny. A mountain village, unlike a lowland town, had only a few riders, and they’d have to divide themselves between hunting the horse and defending the village.

But: Damn stupid villagers, he’d think then, and hate them all; and ask himself who cared, or why he should care if they couldn’t take care of themselves. If they couldn’t take care of themselves they had no business living where they did and least of all crossing hispath. He wasn’t a town rider. He stayed generally to the High Wild, dealt with the convoys, got their precious lumber and fuel oil to them, and minded his own business otherwise. He’d had a bullet burn across his skin, thanks to townsmen.

And then, on a breath, the painful lump in his throat would come back, a stinging in his eyes, a desire, villagers or no villagers at stake, to blow that thing to bloody hell.

The average was anger, and hurt, which couldn’t lead him to sit safe and secure down in Malvey, ignoring the situation, even if at moments he wanted to.

It didn’t lead him straight up to Tarmin bare-handed, mad, and stupid, either. It led him steadily toward Anveney, because he needed a gun. If he could reach their money at the bank in Anveney, he couldn’t think of a better use for what he and Aby had saved for the winter than to buy something to blow so many large-caliber holes in that thing daylight shone through.

Give it a chance at him, the best bait and somehow, in his mind, justice in the offering.

Give it the one chance that thing would have had at him if he’d been with Aby the time she most needed him—and give himthe chance hewould have had if he’d been there, kill or be killed. Jonas had been all prudence. Get the convoy down, leave the rider for the scavengers. No damn wayhe would have left Aby lying at the foot of that slide and not gone down after her, convoy or no convoy; and hell if he wouldn’t have gone into the woods after that thing. Hawley he’d have thought would have had the loyalty to her to leave a safe, well-armed, downward-bound convoy, solo, to track Aby’s killer down. He hadn’t done it. He’d run. Aby had died with nobody near her with the guts to have gone after her killer.

Nighthorses caught the contagion of anger very readily, and believed human images very easily. Sometimes Burn likewise wanted to go

But

And when they reached the cut-off where a horse-trail went west to the rider-stone that sat at the cross-country crossroads, Guil slid down and wished Burn gone to that stone, a route that wouldn’t take him into Anveney itself.

Burn heard his

Burn snorted and ambled off the road, nosing the grass without eating it. Burn left no doubt. Burn didn’t think there were pigs in Anveney.

Burn sulked off a distance, in no hurry. But Burn wouldn’t at all like it once Burn had to smell the smoke.

Burn’s rider, on the other hand, had to breathe the smell from the moment he walked over the rise and caught the wind.

Burn’s rider had to look on a barren land, the smokestacks and the ruin they made, a dusty, barren land oppressive to any sane man’s heart, but clearly some liked it that way.

And utterly silent—a silence that came of leaving not only Burn’s range, but leaving the range of every living creature, because nothing flourished in this land of metal-laden air and dying grass. Walking down the last grassy hill was like walking down into a lake of silence, no easier to tolerate because he’d been here twice before. He experienced the same increasing desolation, the same little catch of breath when he’d had enough and wanted to go back.

No holding of breath would stop the stench or bring the world-sense back. No life. Nothing to hear—not the little creatures of the world that talked constantly to him and Burn; not the noise of a camp, the constant presence-sense that he was used to, in camp and outside one.

It didn’t exist here.

Six huge smokestacks sat on the shoulder of a low hill and a huge town, rivalling Shamesey’s size, sprawled off onto other hills—with little hillocks of tailings around the pits that surrounded Anveney, out across a barren landscape as far as the horizon.

Lakes of incredible poison hues. Smokestacks that lifted the worst and deadliest of the airborne ash above the town, so they said—but only humans, it seemed, could live near those tailings piles, or the run-off basins where the water collected in those pools: white and brilliant blue and bright green, beautiful, if you didn’t know you were looking at death.

Copper-mining, chemical-making… if it was poison and other towns wouldn’t touch it, Anveney would. Let the smoke blow and the water run and seep into the river and run to the sea: Anveney didn’t care.

Anveney supplied all the world with copper, tin, gold, silver, and lead—iron for trucks and guns came from over the Inland Sea, ported in at Carlisle, moved along Limitation River by barge. He’d never been that far east, himself, but he knew coal came inbound there. A handful of lowland riders shepherded those barges along the shorelines and guarded their contracts equally jealously, as theirright—but they based themselves at Carlisle, and went only as far as the zone of die-off, so he’d heard. Coal likewise came from across the Inland Sea, smoky stuff to feed the furnaces of the big foundries and refineries and to supply the lights of Anveney, likewise freighted in by barge—while Malvey sat on natural gas and oil, a source of fuel on thisside of the sea, a mere six days ride to the south of Shamesey.

But it wasn’t distance that kept Malvey oil out of Anveney, or made them buy their fuel from middlemen in Shamesey. It was townsmen politics. Malvey’s oil heated Shamesey as well as Malvey houses, as it did Tarmin villages, in winter emergency. It ran the generators that ran the electric lights, smoky stuff, too, but its smoke didn’t seem to kill the ground.

Anveney smoke did. Anveney smoke ruined the ground in a wider and wider desolation made, as Shamesey claimed and any fool could see, by smoke and downfalling pollution out of Anveney, smoke that didn’t always blow toward the vacant lands, Anveney’s pious claims to the contrary.

Shamesey, lying southeast, had protested and demanded that Anveney shut down its furnaces on those days when the wind was blowing toward Shamesey and its farmlands—but Anveney consistently refused, first on the grounds that it wasn’t possible, the furnaces couldn’t shut down entirely on a given day; and then demanding that Shamesey pay exorbitantly in grain and fuel for any days the refineries were out of operation.

So the two regions quarreled and counterclaimed—it was news the rider camps cared about, since the fools held trade and rider pay and villages’ winter supply hostage to their ongoing dispute. Anveney didn’t need riders to guard their town at all, Anveney said, because their walls and their guards defended them, even out in the remote mining pits.

The stink and the poison defended Anveney, that was the truth all riders knew, and even townsmen in Shamesey had an inkling. The plain fact was that no creature in its right mind would come near Anveney, first for the stink that clung to everything, in that zone where the smoke spilled its most odoriferous content to earth—and second, for the more alarming effects: a stranger to Anveney felt he had contamination on his skin. He’d been here once, himself, and his skin had itched until he’d bathed in clean water, which argued to him and surely to any creature with a brain that it couldn’t be good. It was why he wouldn’t allow Burn close enough to eat the grass on the edge of this place.

But humans somehow survived here. Humans mined and refined the metals, and when Anveney shipped its ingots and sheet metal outside the envelope of its poison, it still needed riders to guard the shipments.

Anveney both needed what its poisoned soil wouldn’t grow or graze, and held its own goods back if it didn’t get the price it wanted. Other towns wanted copper to make the wires for the phone system, which never worked when you needed it—but at least it didn’t draw predators like the radio did; townsmen wanted the phones enough to keep paying riders to fix the lines and guard the crews that put up poles that fell down in the ice storms all winter.

Lately Anveney and its little network of high-country mining camps with their copper and such had all made one union, and wouldn’t sell except at their prices. This was the next escalation of the smoke wars.

So now Shamesey, latest he’d heard, was trying to arrange some kind of terms with Malvey, since Anveney was as desperate for food as Shamesey was for electrics and copper sheet for rich families’ roofs. Shamesey reasoned that if Anveney got hungry enough it might shut down its smoke when the winds blew southerly. Shamesey had made alliance not only with Malvey and itsunion, but with other, smaller towns in the grain belt, which dealt with Shamesey markets, and began to hold back grain and to create stockpiles of copper against Anveney’s price-fixing and smoke-dumping, saying that Shamesey could do without copper longer than Anveney could do without bread.

It was a damned stupid situation. Guil had heard both sides of the argument all his life, at varying degrees of immediacy, and didn’t comment, as riders didn’t generally voice opinions on town politics to their employers or to the truck drivers, whose trade was gossip as well as cargo. Talk like which side was right confused the horses and worried riders, when towns got to quarreling—nobody needed more ill feeling near the horses than they naturally had coming at them, but when the smoke wars heated up, things generally grew uncomfortable; and the smell of Anveney, both the stench and the town-wide atmosphere of fear and grievance, made it hard for a rider not to have opinions. Bad enough the refinery jobs at Malvey, including the chance of blowing sky-high in a truck accident.

But… Aby had argued, in her dealings with Anveney, the pay’s good and I can camp out till they arrange the papers and get the trucks to the gate. I don’t have to go into town but once a trip.

Well for her, he supposed, wondering once, in Aby’s near company, how good in the blankets this Anveney shipper might be.

Gotten his ear boxed, he had—deserved it, he was sure; Aby’d been only half joking when she immediately after pushed him into the blankets and never did answer the question.

Come with me, she’d urged him again, last spring. Talk Burn into it. You’ve got to see the country up there.

I do see it, he’d said. She’d imaged him her route again and again.

And she’d said, pleading with him: With your own eyes, Guil. You’ve got to feel it. You’ve got to be there.

But he’d refused. He’d made his commitment to Malvey; he’d elected to run his risks with the fuel tankers up to Darwin. He had his hard-won customers down south that he didn’t want to let into the hands of anybody else, for fear they might call on that somebody else next time.

And truth be told—he’d grown a little tired of her evasions.

So now he was walking to Anveney town alone, his eyes feeling the sting of the smoke when the wind gusted a fickle current down-valley.

Anveney’s Garden, riders called the place, the area all around and northeast of Anveney, where the soil lay completely bare and prone to erosion, gullies leading to gullies leading to a wash that ran down to a river that ran through barren banks a long, long way before the inpouring of other streams began to put more life into Limitation River than death could take out. Even that far, neither riders or horses would eat the freshwater fish, which grew strange lumps on their bodies.

No riders wintered over in the district, that he knew of, either. During the summer if you looked over from the Tarmin main road, you could generally find a plume of smoke in the hills, a handful of riders resting up for a day or two, waiting for some convoy to organize; they’d wait in that still-green zone, always outside the dead fields.

Only a few weeks ago, Aby had been among them.

Chapter xi

BRIONNE’S FEET WERE COLD, HER FINGERS WERE COLD. SHE TUCKED her hands in her pockets and kept walking, brushed by evergreens which dumped the burden of their boughs and spattered wet snow onto the melting crust.

It was a beautiful morning. It wasn’t golden anymore. She’d walked through that angle of the sun. But it was a shining morning, still. Glistening white, the sun gleamed in snow-melt off tall branches. It was the kind of morning that would lead to glossy melt by afternoon, and a freezing icy crust again by night, in Brionne’s young experience. The snow tomorrow morning would crunch underfoot and make hollow shells where footprints were– and you’d slip walking around the edges of the house where the run-off made thick ice. She knew. She loved the snow.

And when the kids of Tarmin village gained permission to go outside the walls it had always been with riders all about, but Tarmin wasn’t afraid of goblin cats. Tarmin folk and riders both went out to skate on the mountain lake, and Tarmin children, when the riders were near, went out to build snow forts and sometimes, especially if you were lovey with boys, just to walk to the Rim and see the valley, with rider pairs to watch them.

It was scary being out on her own. But she wasn’t truly afraid. Her horse surely knew she was looking for it, her horse was only testing her in making her walk so far from the walls, and if there should be a goblin cat, her horse would never let it come close to her. If there was a nest of willy-wisps, her horse would hear her call and come to her rescue, if she couldn’t, as a rider could, drive them away simply by imaging as loudly as she could.

I’m here, she called to her horse, not with her voice, but the way the riders spoke, the pictures you made in your mind.

And there came… oh, so suddenly you’d never know it had happened… the view of a girl in a red coat, with a blue scarf—of course that was herself. Of course it was. And sometimes, the riders said, you could get that kind of image from willy-wisps, but it didn’t feel scary like willy-wisps, it felt…

… so, so lonely.

She pushed aside a branch to pass between two trees, and suddenly was sure where she was going, so sure she half-ran the next wooded slope, arrived at a clear space in the woods, and in that clear space the sun fell, and in that sunlight… the most beautiful horse, its mane so thick and long it cascaded down its black shoulder, and all the clearing touched by sun that made its coat shine like silk.

Her horse regarded her with one forelock-obscured eye, dipped its head and pawed the snow anxiously before it took a tentative step forward, its three-hooved foot taking ever-so-light a step before Brionne dared commit herself.

“Are you mine?” she asked, and went on, breathlessly, feeling a little foolish to be talking with no human to hear. “My name’s Brionne. I’m thirteen. I live in Tarmin village. I heard you last night. What’s yourname?”

Another step.

“I’m not afraid, you know. I talk with the riders all the time. I talk with their horses. There’s Quickfoot and Flicker and…”

A third step. A fourth. Brionne forgot everything, every word.

The horse stretched out its neck and Brionne quickly pulled her glove off and held out her hand… felt the chill of the air on her bare skin, saw the horse wrinkle its black nose and bare its teeth. The center ones were large and square and yellowed—jarringly real—out of time with this white glisten of morning. The corner ones were longer and sharp; and for a moment staring at them she doubted her safety—but she stayed still when the horse’s nose approached her outstretched hand.

The velvet black lip came down as it reached her fingers. She laughed shakily as she felt the hot, moist breath puff over her hand, she touched the delicately molded softness of the horse’s nostrils as it breathed in her scent.

Another step, hers or the horse’s, or maybe it was both, and she could touch with her fingertips its long forelock. Another step, and she could run her fingers through that incredible long mane and put her arm about the horse’s neck and shoulder, and hug it tight. Its mane was like finest, softest, floatiest wool against her cheek, stirring with any wind. Its winter coat was warm and silky. She let go a shaky sigh, feeling shivery just feeling it.

She knew the horse should tell her its secret name then. “Brionne,” she said, thinking about herself, the way her horse had, imaging

Then she couldn’t see the woods around her. She saw only

Of a sudden Flicker’s hindquarters buckled and she sat down hard and fast, knocked a post askew with her rump, and Tara dropped the pan she was carrying, hot water all down her leg, and ran to Flicker, flung herself onto her knees on the wet straw and put her arms about Flicker’s neck.

There was no more

Tara shook, holding to her, pillowing her head against Flicker’s back. Flicker shifted a little, matter-of-factly seeking a more comfortable position for her forelegs, and Vadim and Chad talked to each other in human words, quietly relieved, wondering if they should try to get Flicker up again.

Tara overheard and thought < Flicker lying down.> Flicker’s legs were tired, and if her legs were too weak and went to sleep under her and they had to bodily lift her, fine, they had the gear—they could do that; and Flicker had moved her forelegs on her own. That was a good sign. Only let Flicker stay down as long as she seemed to need to.

She thought of

Tara just stayed where she was, didn’t want to move, put her head down against Flicker’s ribs and lay there, heart pounding so loud she could hear it, then slowing as she went drifting instantly close to sleep.

Didn’t feel the terror now. Just sleepy. Just tired. Just aching.

Just loved, by friends around her. And sleep was very easy.

Clouds billowed out of the high smokestacks—each of the six of them with its own color and stench. The smoke, black and yellow, was thick enough to create an impression of permanent storm hanging above the town and its environs. Most of the foulness went above and beyond Anveney, but the stinking clouds passing overhead still rained on the town a kind of gritty soot and a yellow, powdery dust that an ignorant rider feared wasn’t only sulfur, although sulfur was certainly one of the taints on the wind.

That rain of ash coated the walls and roofs and buildings in a runny multiplicity of stains. Soot gritted and cracked underfoot, and you sneezed the stuff out once your nose and lungs had had enough. Anveney buildings near the edge wanted repair, not just paint, like Shamesey slum buildings, but essential repair to the ravages of weather and listless years. Shutters hung atilt on upper floors, excrescent rooms overshadowing the walks were propped from below with timbers and, sagging further, with mere boards, at all angles. Porches on upper levels likewise sagged, suspended by chains and cables, a supported slum so bizarrely contrived that whole buildings must rock to the winter gales.

When folk had once built these dwellings, the main street, at least, had had paving stones, limestone quarried north of Anveney. The last of them had not quite sunk beneath the mire; and the filth that swam atop made slick spots in the road where water gathered in rainbow puddles.

The poor of Anveney town mined, that was the system. The ones on the streets were the discarded, the jobless destitute, the old, the crippled, the sick, who sat about on doorsteps—

And there were the predatory disinclined, who, solitary or in groups, wandered the streets. Guil eyed a handful of underagers watching him just too keenly, gangling youths with skin in which soot seemed deeper than the reach of soap, eyes that tracked coldly, and stared in cold estimation at a rider walking down their street.

Guil paid steady attention to them, keenly aware of the silence of the ambient that robbed him of warnings, and kept walking, refusing to cross to the other side of the street.

He walked past, turning his head to glare at them. But he couldn’t hear, once he’d passed. He listened with his ears—warned by no more than a foot moving, spun in the very instant a rock aimed at his back hit his arm. He stared after the fleeing culprits with an impulse which would have given bystanders nightmares if Burn had been with him, but Burn wasn’t.

They hadn’t stayed, all the same. A few other watchers crossed the street out of his path as he walked on, maybe reading his mood from other signs.

Hate lived here; despair; and muddle-headed confusion. He saw it in the faces of the old;—he saw it in the faces of midtown children, cleaner than their slum-side counterparts, but many, many of them whiter than soap could make them. They threw no stones. They only stared, listless and bruised about the eyes.

The preachers said their state was holy and his own was damnation. Himself, he inhaled as little as he could of townsmen paradise and wished for rain to wash the air clean.

If one of them had ever come to a rider and begged—if one had come to Aby—if one of them had ever just hopped a ride with a truck—but none of them that he knew had ever asked. Anveney folk centered all their hopes on the mines, the metals, the mills; they depended like parasites from the moneyed monster Anveney was. It shook them off and they sank in the mud and died—all the while their faith so feared the intrusion of another, alien thought into their minds they’d die before they worked with a horse.

And by what he knew, they equally feared the uncertainties of a rider’s life—meaning hunting for their supper. Anveney folk might haveno supper. But they seemed reassured that they were surethey would have no supper.

They suffered no surprises. The poison above the town did make spectacular sunsets… that was all you could say for it; but Guil doubted they appreciated the colors above their gray, sooted walls. He’d touched enough Anveney minds for a lifetime, among those drivers who regularly came back to this town when they had other choices. He’d tried to penetrate their sullen, argumentative insistence on certainties. They afflicted him the same way dire illness did.

He’d felt an irrational fear ever since he’d passed the guarded town gates, first that the walls were closing in and then that the successive concentric rows of buildings were shifting and entrapping him. Even when the buildings became wider spaced that anxiety persisted, on the broadening way down which, if it were Shamesey, the convoys would come, assembled in the town square with excitement and honking of horns and cheers of passers-by.

In Anveney, depend on it as one depended there were rich townsmen at the heart of everything, there wasa town square, but to his borrowed memory it was all official buildings and rich houses with sealed windows, while convoys assembled and onloaded and offloaded at warehouses outside the town wall, out by the tailings-heaps.

The buildings came in better repair as the road inclined uphill, the pavings mostly clear of muck. Here a shop stood open-doored, with moderate traffic of buyers, and there, the smell of bread from a bakery wafted out locally stronger than the general stink of the valley air. The bakery stood next a house with bright red doorposts and a red and blue door, a level porch with the rail intact and iron bars on the windows. Touches of color became riot further down the street; red beams with blue trim at the corners of neat yellow and white buildings, a carving of flowers on a wall inset—they all had a dusting of soot, and the flowers were black-edged. But the colors were cheerful.

The folk who walked here (more idle folk than in the lower town) wore townsmen’s long brown coats and broad, flat hats, men and women with woolen trouser hems innocent of soot. Children waddled about like stuffed dolls in overcoats on this nippish day, children with round scrubbed faces, more color in their cheeks than in the poorer part of town—no few masked in gauze, leaving only the eyes exposed. They stood and gawked at the sight of a rider walking down the street. Their elders stared, too, and drew the children away.

He’d reached town center, where he was sure the bank must be, an open square with all too many silent minds and staring eyes for his liking, a marketplace not like friendly village markets, with their open stalls where riders sometimes came to deal and rub shoulders with townsmen, but shops with most of the goods indoors, requiring the buyer to commit himself and go inside. The nature of the buildings gave him no cue what business they did.

A woman passed near him, hatted and coated into shapelessness. “I’m looking for the bank,” he said to her, and she evaded him and his question with a brisk thumping of thick heels down the walk.