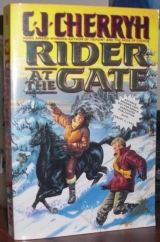

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Burn calmed until that hillside conformed to vague memory, and it resonated with

“What’s he smelling?” Tara asked.

“Horse,” he said. He wasn’t hearing Flicker that clearly—or hadn’t been. Flicker was

Burn went toward that place of open sky, wide vistas.

“Guil, that road’s going to be hell up there, bad drifts. That kid’s coming back here. This is where she’s been coming to. Maybe we ought to fall back, just sit and wait. She’s not going up that road much—”

Up and up the road. Into the daylight.

“Guil!” he heard someone shouting at him.

A horse arrived beside him. It roused no alarm. But for a moment his vision was

Then he saw—

He saw

“No!” a woman yelled, and

He dismounted—no recourse but that as Burn recovered his balance. He landed on his feet and in that split second of landing the vision of

Tara was on foot—Tara was beside him. A gun went off next his ear, rattled his brain, and then

Moon. He had nodoubt. Burn, beside him, knew. Burn sent out a troubled keep-away and Moon stopped. The blonde kid urged Moon forward with

He only then remembered the rifle in his hand.

“Give me the pistol!” he snapped at Tara and held out his hand.

It was

He grabbed the pistol that arrived in his hand. He let go the rifle. He walked forward, <—making love.> It was a hurt horse. A thirteen-year-old kid with a wish, on a horse in mortal pain. He saw it for a blink, but he said to Moon, He said, “Good girl, don’t spook on me, you know me, it’s He reached out his right hand, for the girl’s hand that reached to him. He fired with the left, the gun right under Moon’s jaw. He grabbed the icy fingers, snatched the girl against his chest and spun away as Moon went down—he held the kid crushed against him, blind to anything but the mountain—he couldn’t see, either, for the blur of ice in his eyes, couldn’t feel the ambient for the sudden silence he’d made, the murder of what he loved. He knew Tara was back there, Burn was there. He began to hear. He couldn’t see until he blinked and a shattered sky and a shattered mountainside whipped into order. The girl was in his arms, live weight, but there was utter silence in the ambient and his ears were still ringing. He only saw Tara with the rifle, Tara sighting toward him— Second blink. He began to feel the ambient again. His foot skidded on ice. His balance was shaky. He saw the edge of the road under his right side and veered away from it. He set the girl on her feet, pulled the blanket about her, but she just stood staring into nothing, blue eyes in a tangled blonde mane. He shut her fist over the ends of the blanket, took her by the other hand and walked Something slammed into him, spun him half about in shock, about the time he heard the crack of the rifle echo off the mountain. He kept turning, trying to keep his balance, not knowing where he’d fall— The rifle-crack rang off the mountain from behind them. Tara spun toward the sound and dropped to one knee, with the far figure of rifleman and horse the only anomaly in her sight of woods and snow. She fired on instinct at the distant figure, pumped another round, and looked for her target— But there was only a horse. And the darkness of a body lying by it. The man didn’t get up. She stayed still, rifle trained on that target until her leg began to shake under her. Burn imaged She didn’t want to shoot it. Didn’t want to. She wanted But it wouldn’t. Damn it. It wouldn’t. She put three shots near it. She didn’t want another rogue on the mountain; but then Flicker charged into her line of fire, and she couldn’t shoot. Burn followed, balance tipped, wanting She staggered to her feet, gasping for breath that wouldn’t come, Flicker and Burn both going for the horse. At the last moment it turned and ran back down the way it had come; Flicker and Burn stopped in their charge, circled back a little and maintained a threatening posture. That horse’s retreat told her the man she’d shot was dead. That Flicker and Burn both stopped told her the horse was reacting as it should, in ordinary fear and confusion. It hesitated in its retreat, probably querying its master. Burn called out a challenge that echoed in the distance. Then it launched into a run, shaking its mane, going farther down the road. Nighthorses didn’t altogether understand death. The total silence of a mind confused them dreadfully—in which thought— She turned to see Guil getting up, leaning to one side, trying to stand. The girl just stood there, staring at nothing. She started running. She saw from Guil’s face he was in shock, even before the horses came running back to them, and she caught “Stay down,” she said to Guil, and made him sit. She could feel the wound as if it was in her own side—felt entry and exit, as the numbness of impact gave way to “It could be worse,” she said, and shoved his hands away. There was a fair amount of blood, but it didn’t look to have hit the gut: it had gone through muscle and it was swelling fast. Guil kept trying to get his knee under him, It helped the pain. She could feel it. He was going to want to get to the shelter back there and lie still a while. She answered his confused memory of the gunshot with “Kid get hit?” he asked in a thready voice. She cast a look at the girl who was still just standing there, holding the blanket. Staring at nothing. There was nothing in the ambient. Not from her. “Didn’t touch her. Hang on, all right. Don’t faint. All right?” “Yeah,” he said, and pulled his coat to and started getting his knees under him—the fool was going to get up, and he couldn’t stand; but he got the rifle and leaned on that before she could get her arm under his. Burn was right there, nosing him in the face, in the shoulder, anxious and about to knock him over. He swatted Burn weakly with his hand and wanted She had a wounded man on a mountain road bound and determined to pick up a girl who weighed most of what she did, and she didn’t give a flying damn if the girl stood there and froze. But hedid. She left him to the wobbling assistance he could get from the rifle; she grabbed the kid herself and dragged her with them, with a wary eye toward the downhill road, in case she’d been mistaken about the man being dead, in the unlikelier case the horse had been mistaken. In the far distance she saw a group of riders coming up. Guil stood beside her, leaning on the rifle, trying to reason out who it was, too, and coming up with no better answer: “ Threeof them,” she said. “Maybe it wasn’t Jonas down there, Guil.” “I don’t know,” he said. The ambient was confused and muddled with his thoughts. Things from downland. Things from the village. From a long time ago, maybe. The shock was catching up to him, and he found a snow-covered lump of rock to rest on, rifle in one hand, his elbow tight against his side. Burn came up close by him. Tara went and got the kid by the wrist, got the pistol from where it was lying in the snow, hauled the kid to the side of the road behind Guil and made her get down behind the rocks, out of the way of flying bullets. She kept the pistol in her hand as the riders kept coming. She didn’t need Guil’s recognition to know them. She had a clear image of “Whoever shot you,” she said to Guil without taking her eyes off the riders, “I got him. Whoever it was—I got him. Guil.” Flicker moved in. Made a solid wall behind them, with Burn. A wall giving off Guil put the rifle butt on his leg. Lowered it, slowly, and the three riders stopped a fair distance down the road. “Guil?” the shout came up. “Guil Stuart?” “Yeah,” Guil shouted back, and hurt from the shouting. “So what’s your story, Jonas? What’s the story? Does it say why Aby’s dead? Does it say why I shot Moon, Jonas? Does it say you’re a lying son of a bitch thief, Jonas? I know why you’re up here. I know what you’re after, and you don’t go up this road. You go to hell, Jonas!” “Hawley wants to talk to you, Guil.” Burn wanted But Guil sent, “Who’s that I shot?” she yelled down at them. “Guy named Harper,” Jonas called up. “Nothing to do with us.” It was somebody Guil knew. A lot of confused memories hit the ambient, an old fight. Another mountainside. Another edge of the road. She didn’t believe it had nothing to do with present circumstances. She waited. She left Hawley to Guil. She still had her eye on the others. Guil waited. Kept the rifle generally aimed at Hawley, as Hawley came up within easy range. Then he brought it on target. Hawley stopped. Hawley looked scared. With reason. Ice had followed him up the slope and arrived beside him, the way Burn stayed by him. Ice was loyal. So had other things been. “Moon’s dead, Hawley. It was Moon gone rogue, you know that?” “No. I didn’t. I swear I didn’t, Guil. It couldn’t have. I feltit!” That, in the ambient, was the undeniable truth. But it was the truth as Hawley’d seen it. “You left Aby’s horse, Hawley, you left Moon hurt, you left her crazy. Moon maybe had a chance—she was a good horse, she never did a damn thing against the villages until she took up with that damned stupid kid, Hawley! You got yourself down that mountain and you left Moon on her own, the way you left Aby lying there for the spooks!” “I saw that horse go over!” That was the truth, too. He blinked, he at least considered a doubt of Hawley’s guilt. It was what Hawley had seen. But it wasn’t what he’d just faced up the hill. It wasn’t the truth lying there in the roadway, with a bullet in its brain. “Guil, I’m sorry. I swear to God, I’m sorry. I wouldn’t’ve left her. I saw ’em go, I swear. There was rogue-feeling all over—it wasa rogue—” “It wasn’t any rogue driving that truck, Hawley. I can see that “I saw it, I did see it, Guil, I swear to you, I swear to God—” The image rebuilt itself. “You want to tell me, Hawley? I don’t care about the money in the account. I don’t give a damn. I want you to tell me what happened to Aby.” “I was going to tell her,” Hawley said. There was “Tell me. Use words. I want to hear it, Hawley.” “Jonas says—” He brought the rifle up. “I don’t give a damn what Jonas says. You tell me. About the gold, Hawley. What about the gold?” “We didn’t know about it. We didn’t know! She just thought we did!” He was “Guil, I swear—we just guessed it. I mean, anybody could guess, the truckers were guessing—” “Keep talking.” “And Aby was mad about it. Aby didn’t want anybody to know. And by the time we got up to Verden she wasn’t speaking to us– she didn’t want to be around us. I think she was rattled, she thought she’d spilled it, but, hell, we knew, Guil, once we was on to it, we could get it from folk all round us—” You knew when Hawley was outright lying. And sometimes when Hawley was telling all the truth he knew. And this was, he thought, the truth as Hawley knew it. “Guil, I swear to you—” His arm was shaking. He let the rifle rest on his leg again. “I’m listening. Keep going, Hawley. You be thorough. I’ve got nothing but time.” “The truckers, they caught it, too. You could feel the upset all over, and this truck, its brakes weren’t good. They was spooked, didn’t want us to pitch that truck out of the line, and Aby, she told me she wanted them hurry up with that truck. I come along, you know, just walking the line—” “The gold.” “Yeah. I mean, Guil, they didn’t want to have to move that box. And we wasn’t supposed to know about it. I don’t think they trusted any of us. And Aby was madder ’n hell all morning. But they give me money, Guil, they give me money, they say shut up, don’t talk about the brakes—and I had the money, and they’d fixed that brake line. I mean, they really fixed it. But then I’d got to worrying about it, I was going to give it back, I was going to tell Aby—I was going to tell her, Guil. I knew it was wrong to take the money. But she give the order, we started rolling then, and she was up front, and we was in the rear—Guil, I knew this one turn was bad, but I didn’t think the drivers was going to risk their own necks. Aby was worried about the weather, worried about us getting down to the meeting-place, maybe after dark, but we’d get there—” “So it was just the brakes. And there never wasany rogue.” “There was a rogue, Guil, there was for sure a rogue—” “ Beforethat truck went off? Or later, Hawley? Was there a rogue when you got to that turn? Was there a rogue there then?” “I don’t know, Guil. It was there, was all.” “I shotMoon, Hawley. Moon was the rogue.” “Moon’s dead. I saw her down there on the rocks, I saw It hurt, that image. He thought about pulling the trigger and blowing Hawley off the mountain. He thought about not dealing with it at all, anymore. But Hawley—was so damned earnest, Hawley believed what he was saying. “Hawley, go back and tell Jonas I want to talk to him. Tell Jonas get his ass up here. And get yours out of my sight. Right now.” “Guil, I’ll give you the money—I swear, I’ll give you the money—I was going to give it to you—” His finger twitched. Twice. Stayed still, then, the gun unfired. Sight came and went. “Only thing that recommends you, Hawley. You got a single focus. Always know where you are. Always know what matters, don’t you? Truckers put money in your hand and you don’t know how to turn it loose. You get the hell down that road, Hawley, tell Jonas I said get up here. Now. Hear me? You tell Jonas get up here or I’ll blow him to hell. Hear?” “Yeah,” Hawley said, anxious, confused as Hawley often was. “Yeah.” He swung up on Ice, and rode fast down the hill. Tara said, faintly, “I think it was the truth, Guil. But it doesn’t make sense.” He was glad to know that. He didn’t trust his own perceptions. He left the rifle over his knee. He watched as Hawley came down to Jonas; and Jonas looked uphill toward him, and then started up toward him. “Give the son of a bitch credit,” Guil muttered. Tara said, his voice of sanity, “You asked him, Guil. Hear him out. You asked to hear him.” So he waited. He sat with the wound beginning to throb, and knowing if he shot now he was going to have to shoot from the hip. Jonas rode up all the way, on Shadow. And sat there, to talk to him. “So?” Guil asked. “Aby didn’t trust you. Truckers bribed Hawley not to tell about the brakes. And the brakes failed. Not a lot of people trusted you, Jonas. What happened up there? You tell me. I want to hear this.” “We knew there was something on board. Aby didn’t like us knowing. Truckers suspected. And they spooked. Didn’t want to stop, didn’t want to camp out on the road on that height and they didn’t want to leave that damn truck on the High Loop. Guil, I swear to you—Aby didn’t trust anybody. Shedidn’t want to stop. She was spooked—she knew we knew something, we tried to talk to her, and she wouldn’t have it. It spooked the drivers—” “Her fault, is it?” Jonas shook his head. “Brakes failed. Hawley told you—” “Hawley told me about the brakes.” “They were taking it too damn fast. Riding the brakes too much. Aby wasn’t with us, she wouldn’t ride near us. The truck went runaway—she was down there. I swear to you, Guil, we did everything we could. It just happened—so fast—” “She and Moon went over, did they?” “Both of them.” “That’s a lie, Jonas.” Shadow spooked. Made a move forward that Burn opposed with a snarl and a threatened lunge. And Jonas didn’t answer him. Jonas didn’t know the truth. “I saw her,” Jonas said. And it was that image again, He stayed still, his finger on the trigger. But the pieces fell together, finally. He said quietly, “She fooled you, Jonas. Moon fooled you. You understand. Moon wantedto be down there. In her mind—she wasdown there. And wasn’t. She was up on that hillside looking down the same as you were, and you saw what sheimaged. I tell you, Jonas, I believe you. I believe you about Aby. I believe you about the gold. Which I think is what you came up here to find. Is that true, Jonas?” “Yeah,” Jonas said after a moment. “Yeah. —But I didn’t know Hawley’d robbed you, Guil. I’d no idea.” “Just going to turn that box in yourself, weren’t you? Nobody the wiser. You, with big credit with Cassivey.” “I’d have dealt you in.” “Yeah, me, who never took the Anveney jobs. I tell you, Jonas, you go on down to the junction. You take that downhill road. And I want you to take Hawley somewhere we won’t meet for maybe, two, three years. Then maybe we’ll talk. You understand me?” “Guil, we’d take you down country.” “I’ll handle it. You get to helloff this mountain.” Jonas stayed still a moment, turned Shadow half-away, then looked back. “There’s some kids, Guil. Rider named Danny Fisher, couple of village kids, on this road. Looking for you. They didn’t have anything to do with this. You want to sweep them up, see they get somewhere safe? Road down’s hell when the snow builds up.” “Fisher.” “You know him? He knows you. Horse named Cloud.” He couldn’t place the name. But he knew, in one of Jonas’ rare slips, that Jonas had gotten three kids out of Tarmin. Got them on the road. Wanted them safe. Personally—and earnestly—wanted them safe. A lot like the man he’d known a long time back. He almost relented. Almost. Said, “See you another year, Jonas.” So Shadow went, and Jonas with him. And the ambient was only themselves, and the horses, and the wind. Chapter xxii YOU TAKE CARE!” TARA CHANG SAID, WHEN THEY WERE GATHERED in the yard of the rider-shelter, and take care was what Danny meant to do, personally. He’d said his good-byes to Guil Stuart inside: Guil wasn’t on his feet, but would be, they had confidence of that. Meanwhile Burn was taking advantage of an open door and a sunny day. So was Flicker, and Burn was sending Cloud a serious warn-off, That was one reason for leaving. The kid bundled in the travois was another: Brionne Goss and her brothers weren’t comfortable companions for nighthorses in a winter shelter, and the first crystal-clear day, with the sun burning bright in the high-altitude sky was a chance Danny knew they couldn’t turn down. Guil didn’t mind much, Danny figured that for himself. Guil got a winter-over with a damn pretty woman, all to himself, and had a village down the way with a store full of supplies. They’d shared Down the mountain or up the mountain wasn’t Burn’s urgent concern. But Guil said, “If you go up, don’t linger in the shelters.” And Tara: “The mountain doesn’t give you many days after the snows start. Either one’s dangerous. You make time. Make time, all you can do.” So in this bright, clear morning, they went, and he thought up, all considered, was the best choice. Cloud wasn’t against it. Avalanche on those lower slopes scared him personally worse than the high, hard climb did. Jonas had taken the chance. He thought maybe Jonas had won the bet with the mountain; but they’d been holed up and couldn’t prove it. The days that that downward road would be passable were getting fewer, if they weren’t gone already. And Guil said he hoped Jonas made it. About Hawley, Guil still wasn’t sure, but he said Hawley was a thorough-going jerk, that was what he was guilty of, and he’d forbear to shoot Hawley, in colder blood, when next they met. Assumptions. Assumptions was the thing that had been so fatal. Lives that touched one another and never knowing they’d touched at all. Aby Dale had never figured, when she’d died, that she’d have cost so many lives. Jonas Westman and his friends had never figured, when they came clear down to Shamesey, that they’d bring rogue-taint with them. Likely, was Danny’s private opinion, that the disturbance in his own family owed something to the contagion the Westmans had brought; likely that Harper’s private vendetta owed something to it, too. Harper had been a haunted man. And rogue-craziness had been very close to what drove him. The man had carried a grudge for years and, crazy-mean that he was, had had it set off by something, maybe rogue-sending, maybe just the scent of blood in the ambient when they’d shot at Guil down by Shamesey, and a hunter-sense when Guil had taken to running. Maybe then in Harper’s head the balance of fear had shifted and he’d seen his chance to settle old scores. But it hadn’t been a good place, the mountain hadn’t, for a man with a guilty past. A rider could lie to other riders, sure, but he had to lie to himself first, had to lie to himself. And Guil Stuart hadn’t had a thing to do with Gerry Harper’s death. Stuart hadn’t known that Harper was on his tail, hadn’t even known how Harper’s brother had died. A kid who’d come up from town had had the pieces of it shoved at him, that fell into place once Guil told what he knew: a whack in the head from a winch cable, a partner dead, Gerry Harper going off from Ancel in a fit of rage, the Harper brothers not dealing with each other any more for years. “Gerry was all right,” Guil had said. “A lot more reasonable than his brother. I got along with him. —So Ancel shot him.” Guil was surprised and sad. That came through the ambient. Harper believed his brother had gone rogue. “Maybe he did,” was Guil’s opinion. “God knows. I don’t. So Ancel shot him. Shot his horse.” At a campfire. Late one night. Harper had told himself it was all Guil’s fault. Told it well enough at least other men had followed him up a mountain looking for blood. Harper had found blood, all right. They heard his horse at night. Spook came in looking for him—but it wasn’t a rogue, itself, just lonesome. And they hadn’t the heart to shoot it or the guilt to let it haunt them. Harper’d taken a shot at Guil at Tarmin gates; he’d taken his second at the start of the Tarmin Climb. But Harper wasn’t the marksman Tara Chang was. She’d snapped off that one shot and nailed him dead through the chest. So all Harper’s hate, all Harper’s craziness had ended right there, in the snow. The horse mourned him. Nobody else did. Guil hadn’t known the Westmans were on his track, either: when he’d found out, he’d blamed them for the shot at Tarmin village and wouldn’t trust them. He damn sure hadn’t known Harper and his lot were on his heels, hadn’t remotely expected the shot out of nowhere that had gone through his side. He hadn’t, he swore, cared a damn about Harper, hadn’t spoken to him for years. But Harper’d paid his life for a grudge Guil didn’t know Harper was carrying. And come to find out—Guil had had no idea in the world there was a kid named Danny Fisher. Riders weren’t prone to polite lies: the horses didn’t let them do what townfolk did, and Guil didn’t deny there’d been a rainy afternoon on a porch, and a kid asking him questions, Guil just didn’t remember him. All the way he’d tracked Guil up on this mountain to pay a debt Guil didn’t remember. In his way he supposed that he was as crazy as Harper was. But it was a debt he still held valid. He’d heard. He’d listened. He’d learned. He’d remember some time when some kid came to him: he’d know what he said could save some kid’s life and he’d take the time. He might not remember doing it, either. He supposed the moments that came on you to do something good or something evil weren’t necessarily lit up in flaming letters. The things you assumed all needed looking at, and the way you answered a kid’s asking help needed looking at; if you mistook as few as possible of the former and did as much of the latter as you could, the best you could while doing your honest work, he figured that answered all morality a rider was responsible for. That and his ties to his partner. He wouldn’t ever forget the way Guil had come after Aby Dale. He hoped some day to have a partner like that, man or woman. It wouldn’t be Guil. And it shouldn’t be. He couldn’t give anything in that relationship. He could only get. And maybe Tara Chang was it for Guil. Or maybe she wasn’t. A winter in a one-room cabin might be a start on finding it out. Meanwhile he had two boys in his charge. Carlo and Randy; and a kid who might never get any better: Brionne Goss. He knew things he didn’t need to tell. He was, right now, their best hope of living. So it was a down-payment on the debt he had. “Come on,” he said to the boys, and sent Cloud on ahead to break the trail, Cloud’s three-toed feet being quite adept at doing that. It was what Cloud was born to, the High Wild, and the mountain.