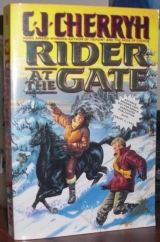

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

He suffered a flare of anger, and half-smothered it before he remembered that Burn wasn’t there to spread it around the area—but he couldn’t heara damned thing, either, not cues, not intentions, not directions to where money changed hands.

A merchant in thick sweaters was tending his out-front display goods, offering them to passers-by, woolens, as happened—fine knit-work in muted colors; and, offered inside (a sudden realization of the logic of such indoor shops), they’d smell better. He thought if the prices were reasonable, if he had money left after finding a gun, he might come back and buy one of those warm sweaters.

In that case, the man could damned well direct him. “The bank,” Guil said, raising his voice to be sure he couldn’t easily be ignored. “Sir, I’m looking for the bank.”

A scowl, as the man arranged a sweater on a cardboard cutout of a man. A reluctant nod across the square to buildings on the other side. “Bank,” the man said. That was all.

“Thanks,” Guil muttered, jammed his hands deeper into his pockets and walked across the square, past waddling, gauze-masked children and clusters of their glum elders who stopped their gossip to stare. God, he wanted out of this place.

He couldn’t swear to what building the man had indicated. He thought the likeliest candidate for a repository of money was the important-looking building with the bars on the windows: it didn’t look to be selling anything, there being no displays, but there was writing on the windows and the door, and though he couldn’t read, he’d never known anybody to write on windows of a private house.

The door was open, seeming to invite entry. So he walked in, onto a bare board floor, facing a grillwork, an armed guard, and a single young man at an undefended desk out front, while the rest of the employees sat at desks securely behind those formidable bars, which led one to wonder which ranked higher.

“Is this the bank?” he asked the guard.

“Seems so,” the guard said, looking him over. Then the young man at the desk, a thin, nervous fellow, said: “Help you, rider?”

That was the most politeness he’d had in Anveney. He walked over to the desk, folded his arms, said, dubiously, “They say I can draw out money here I put in at Shamesey.”

“Yes, sir. If you’ve the account number and proper identification.”

You could have blown him over with a light breeze. It couldn’t be this easy. “I know the number. I memorized it. My name’s Guil Stuart.”

“You’re supposed to have a card. Do you have one?”

Yes, they’d given him a card. He’d very few places to store such things. He fished in his inside breast pocket, not entirely sure he had it, but he found a little white paper, a little the worse for wear. He hoped they didn’t mind wrinkles.

The desk man looked at it and said: “Seems in order. Would you step through to a desk, sir?”

Sir, yet, from a townsman. Guil received the card back, decided he should keep it out, and as he followed the young man, heard a click that put him in mind of guns. It made his nerves twitch. But the guard had only opened the bars and let him in to the area where the men and women sat at safer desks.

“Help you?” the nearest woman asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, and came and offered her the evidently important card. “I’d like to take out some money.”

“Certainly,” the woman said as she looked at the card.

“I put it in at Shamesey,” he said, still unconvinced the bank was going to work, or, more to the point, that it was going to work for a rider.

“That’s fine, sir, the lines are up. No trouble at all.” A waved gesture at the chair beside her desk. “Sit down. I’ll be right back.”

The woman got up, taking the card with her, which he didn’t like, and walked back to a door she closed behind her.

Fancy townswoman. Nice clothes. Flimsy shoes that never saw mud. Behind that door was evidently the place of moneyed secrets and decisions, and Guil told himself that Aby had been right and this banking thing evidently did work. He’d personally had the feeling, putting hard-earned cash into the bank at Shamesey—a place where they took your money at an outside window, and you stood in the street—that he might be throwing it away. He’d never remotely thought that he’d be collecting it and Aby’d be gone.

He sat and he sat, feeling awkward, waiting for the woman to come back, and wondering finally if there was trouble with the phone lines. Wondering if there was some glitch-up, maybe the condition of the card—a few rainstorms had blurred the ink in spots, and he hoped it hadn’t blurred anything important.

Finally, finally, the woman came slinking back, not so crisp, far from cheerful, and not alone. A frowning older woman walked behind her, an older woman who scarcely got rid of her scowl as she extended—as Guil was getting up—the offer of a businesslike handshake.

The young woman said: “This is Yolande Newater, Mr. Stuart, president of Anveney Trust.”

“Ma’am,” Guil said, and suffered his hand to be shaken by a cold, boneless grip.

“Mr. Stuart,” Newater began. “There seems to be an embarrassing problem.”

His stomach went sour. He recovered his hand, folded his arms, tried to keep his temper under control. “That’s the card they gave me when I put the money in. That’s my name. I put money in at Shamesey. They said I could get it anywhere there was a bank and a telephone.”

“Yes, sir. It should be. However.”

He frowned, not understanding this ‘however.’ Frustration boiled up, maybe too fast. He tried to hold it in. “I put in five hundred sixty and change.”

“Yes. I’m not disputing your word, Mr. Stuart, or the card. Shamesey Bank confirms your deposit. I just talked to them.”

Amazing idea. Just talked to a bank in Shamesey. He’d never been the subject of a phone call before.

He didn’t think he liked it, in present instance. “So where’s my money?”

“I trust—” Newater looked intensely uncomfortable. “I trust you know the co-holder was reported deceased.”

“Dead.” He didn’t like vague big words for plain nasty facts. “ Dead. I know.”

“There was a new employee at the counter,” Newater began. Then: “This is awkward.”

“Just say it. You lost the money?”

“We don’t lose money, Mr. Stuart. There was a legitimate claimant.”

“What’s a claimant?”

“A next of kin.”

“Next of kin. Hawley Antrim?”

“Mr. Antrim came in with identification. He was listed…” Newater held out her hand and the other woman, silent, standing by her desk, snatched up a paper and handed it to Newater. “Right here, as Ms. Dale’s next-of-kin.”

She showed it to him, as if it was some special proof that cleared her. It was marks on paper, so far as he was concerned, and he wanted it out of his face.

“Hawley Antrim walked into this place and said he wanted the money. He wanted the money?”

“Either party can close the account. The right descended to Ms. Dale’s legitimate heir. Mr. Antrim was listed on the appropriate paper—”

“The hell with any appropriate paper! He had no right!”

“As Ms. Dale’s heir—”

“He’s a cousin! I’m her partner!”

“It’s not that way on the document, Mr. Stuart. There’s recourse through the court, if you care to sue Mr. Antrim, but that’s not our business. We have to disburse funds to the persons on the card.”

“I gave you the damn card! My name’s on it, right?”

“It is. But—”

“Then give me the damn money!”

The junior woman jumped. Newater frowned and said in a shaky voice, “Mr. Stuart… this is clearly an emotional situation. I ask you—”

“I’m asking you for my damn money, woman. You had no call to give it to Hawley Antrim.”

“Clearly the terms of your partnership weren’t defined in our records. I’m in no position to evaluate the deceased’s intentions in writing regarding another party. I can only follow what information Ms. Dale put on her card when she set up the account.”

“Aby couldn’t read.”

“She clearly answered questions. One of those questions involves heirs and succession in the account.”

“She didn’t know about any succession. You and your words, they wouldn’t mean anything to her, she wouldn’t know what any succession was, any more than Hawley does. That son of a bitch just walked in here and said he wanted Aby’s money, wasn’t that what happened?”

Newater said, aside, hurriedly, “Lila, call Peter.” And to him: “If you’ll just sit down, Mr. Stuart, —”

As ‘Lila’ dived away like a scared cat, running for help: he had no trouble figuring, and he looked about to see where ‘Lila’ was going, jumped as Newater touched his sleeve—he wasn’t usedto being touched. “Look,” he said. “Fair’s fair. We can argue later. I lost my gear. I need a couple hundred. You just give it to me, and we’ll talk when I come back. Minimum, I need a hundred. Rifle and shells.”

“I beg pardon.”

“I need a gun.”

There was appalling, appalled silence from the woman. A shocked stare.

“I ama rider, ma’am. I need the gun to go up to Tarmin. Give me the hundred and we settle it next spring.”

“Mr. Stuart, the right to the money passed to her next of kin. I can show you right on the authorization card—”

“Then some damned fool asked her the wrong question, that’s what I’m telling you. They asked her her relations, they didn’t ask her her partner who’s sharing the account!”

“She had that option. She chose to list Mr. Antrim.”

“She didn’t damn choose!” A hand grabbed his arm from behind. He turned around with the simultaneous knowledge it was a man, and he didn’t question whether the grip meant business: he assumed it did and he grabbed a shirt, twisted, stuck out a foot and the man hit the floor. Hard.

The man, the door guard, went for the gun at his hip from that disadvantage and Guil didn’t stop to think—he kicked the hand before it had the gun clear, and the gun went spinning across the floor, the injured hand flew up to be cradled by the other hand, and townsmen were screaming and diving everywhere. Iron bars clanged and shut.

“Hell,” Guil said, not pursuing anybody. The man with the sore hand was still lying on the ground, the barred doors were shut. Guil walked over where the gun was, figuring not to leave thatin play, and the middle-aged fool scrambled up and tried to jump him from behind.

He didn’t shoot the man. He didn’t pull his knife. He didn’t hit the man with the gun. He just dodged, the man being low to the ground in his dive, shoved him fairly gently as he passed, and the man hit the ground as all of a sudden a bell began to ring.

The man probably realized now he’d been a fool. He sat up on the board floor looking foolish, there wasn’t a bank worker in sight except him, and Guil held the gun by the trigger-guard, so anybody could see he wasn’t holding it on the man.

“I’d give you this back,” he said, “except I’m tired of hitting you. You want to open the door?”

“Can’t,” the guard said sullenly.

“Then get—”

Runners thundered up to the open outside door, jammed up in the doorway and sorted themselves out with leveled rifles, aimed toward them through the bars.

Guil dropped the gun from two fingers. Thump, onto the boards.

Somebody, then, had to go outside and around back to get a key from Newater.

Ignoring the leveled rifles, Guil rested his rump against a table and stared glumly at the guard, who was getting to his feet, encouraged by the firepower.

Guil was mad. He was damned mad. He was scared, deep down. He had to get out to meet Burn by sundown, or Burn was going to get dangerously restless. He didn’t think the guard was going to back his story. And it didn’t look good from where he stood.

“He’s got a knife,” the guard said.

“You know,” Guil said disgustedly, “you’d be a lot smarter to wait to tell them that, until they find the key.”

“Hand the knife out,” one of the uniformed police said.

“You can come get it.”

“I said hand it over.”

Hell, he thought, he wouldn’t improve the ambient by arguing the point with four rifles aimed at him. He walked over to the bars and took out the knife, tossed it out through the bars.

“He’s a borderer,” a cop said. “He’s got more than one.”

“You want the other?” He bent and took it from his boot, tossed it out. “That’s all.”

“Don’t believe it,” the cop said.

Steps sounded fast behind him. He turned to side-step the fool rushing him, and something jabbed him in the back of the head. Stars exploded. The guard hit him, knocked him against the bars: hands grabbed him, held him.

Second crack across the head. He jerked to get free and more hands than two men had grabbed him through the bars and held him there. The guard hit him in the gut.

It was a stand-still when the man came back with the key. He didn’t move and they didn’t hit him until they had him outside the bars.

Then the guard thought he’d get one more in. Guil dumped the rightside man over his back, got a clear target with the guard staring stupidly at him and decked him.

Before an oncoming rifle barrel swung into his vision.

Chapter xii

THE PAIN BLURRED THE SKY. BUT THAT SKY WASN’T BLUE. IT WAS A wooden ceiling, a bare electric bulb for a sun. He had no idea where he was.

But Burn wasn’t there.

And on that stomach-dropping realization, he panicked, staring into this electric, burning sun, trying to reconstruct his route to this place.

Aby was dead, up above Tarmin. That was how everything connected. He was lying on his back on a bare board floor with days-old pain in his leg and recently inflicted pain at various points about his skull.

He’d not realized what it was. Not until the second shot.

He’d slid down, given Burn no choice… he’d thought.

But Burn had charged the mob instead of running away—gone at the townsmen mob dead ahead, and, dirty nighthorse trick, wasn’t where he imaged he was.

He’d… damned well been where the mob had thought he was: third shot, and he’d caught it—it had knocked his leg out from under him and sent him sprawling downhill on the dry grass. He remembered.

He thought they were coming to rescue him, he’d thought they wouldn’t let the town take him: camp rights over town marshals—

< People shouting at each other, while he faced the down-slant of the hill, trying for his very life to get up…

He didn’t remember, after that. For a moment the next connected instant seemed here, under the electric light.

Aby was dead. More… more than that. Aby had died.

But he couldn’t go into that pit yet. There was something in there he couldn’t deal with, a darkness he couldn’t escape if he went in there without understanding where he was now…

He drew a deep breath, about to move.

And knew the smell. Anveney’s stink.

How long ago? God, how long ago?

He rolled over fast, leaned back on his hands as the change of altitude sent pain knifing through his skull. Dizziness sprawled him back onto the floor, onto the lump on the back of his skull.

Stars and dark a moment. He tried it again more slowly, made it halfway.

No furniture in the room, except a bucket. Shut door. No window.

< No window.>

Didn’t even know he’d gotten up. He was plastered face-to on the wooden wall as if he could pour himself through it, arms spread, shaking like a leaf—and deaf, absolutely deaf to Burn’s existence. The whole world had left him: sound, sense, everything.

But the raw, rough wood under his hands was real. It proved heexisted.

He could still smell the stench of Anveney around him. That proved something, too, but he couldn’t hear a living soul.

His heart was pounding. Sweat stood cold on his skin. He couldn’t let go of the wall. Couldn’t keep his legs under him, otherwise… couldn’t depend on his balance.

First thing a rider knew: panic killed. Panic led to crazy. Panic gave the advantage away, free to all takers. The sane, thinking man knew he was in Anveney, knew Anveney had no horses in reach to carry the ambient… but… God, he’d never in his life waked up deaf to it; he’d never been in a room without windows, he’d never not known how he got to a place…

He persuaded his knees to hold him—edged along the wall, unsure even of his balance, to try the door.

Locked and bolted from outside. Of course.

He tried to shake it. He slammed the center of the door once, hard, with his fist, and heard only silence, inside his head and out.

Burn—

Burn would be in deadly danger if he came near the walls, and Burn would do that if he didn’t get back before dark.

Burn would come for him, knowingthe danger, within range of the rifles that guarded the town… but Burn wouldn’t care. Burn would come in.

He didn’t know how long he’d been out. He couldn’t, in this damn box, tell day from dark, no more than he knew east from west, and he couldn’t count on any rescue. There was no rider camp outside Anveney walls, no camp-boss to negotiate him out—in autumn, there probably wasn’t another rider within 10 k of here, nobody to know if he didn’t come out of this town.

Nobody but Burn.

Townsmen would know there was a horse out there waiting for him. They’d know the hold they had on him—that whatever they wanted, he’d do, rather than have harm come to Burn. That was surely why they’d shut him away like this; they surely had to want something from him, besides some stupid townsman penalty because a rider inconvenienced a bank that shouldn’t have handed out money to a man that didn’t have any right to it—

He remembered. Damn Hawley!

And to hell with the money. He’d have walked out once he knew they weren’t going to give it to him—he’d have left their damn town. He didn’t think he’d pulled any weapon on them. He didn’t remember any. They didn’t need to lock him up in a box and shoot at Burn, who was—surely—surely old enough and wary enough to give them hell without putting himself straight-off into some wall guard’s riflesights.

But he couldn’t depend on that. Hehadn’t done too well at escaping town guards, himself.

He staggered along the wall, one side to the other, wasn’t sure what it contributed to the solution—his leg hurt, his head hurt. It seemed moving might clear his thinking, maybe; maybe hurt less than standing still. But if it helped, he couldn’t tell it.

He bashed the door again, hammered it with his fist, in case someone could heair. He didn’t think all that much time had passed, but he wasn’t sure: it could be getting dark. Burn could be getting restless, waiting for him.

Saner to sit down. Didn’t want to stop moving. Had to have something to do, not to think, didn’t want to think…

Damn, dead, stupid town…

Knees ached and wobbled. He began to get up a charge of anger then, and braked it, in lifelong habit—

But it didn’t matter. They couldn’t hear that, either. He could wish them in hell.

He bashed the door with his arm. Twice. Kicked it, with the bad leg, because he could only keep his balance on the sound one; and that hurt so bad he had to use the wall to hold him up.

Hinges were outside. Door had to open out. No handle on this side. No hinges to take apart. But if the door opened out… maybe he could kick it open, maybe hit it with his shoulder until he split the upright.

He backed off several steps and rammed it. Once. Twice. Felt it give. Shake, at least.

He heard something then. Footsteps. He’d raised notice of some kind.

Voices outside. He tried to understand them, but his own heartbeat was too loud in his ears. He shoved back from the door, stood back as the bolt shot back outside and the door opened.

He wasn’t at all surprised at the three badge-wearing marshals with guns leveled, reinforcing the guard who opened the door. He lifted a hand, palm out. “No trouble here,” he said, trying to keep the ambient calm. And he couldn’t resist it: “ Helpyou with something?”

“Mr. Stuart.” The man who’d opened the door indicated he should come out, so he came out. The men with guns backed up, maintaining their advantage. “Someone wants to talk to you.”

“Fine.” He hoped somebody wanted to talk to him. He hoped somebody had a deal to offer him to get him out of here, and after that, he didn’t remotely care if Anveney burned down.

So he walked obligingly where the guard indicated and the man led, down a dingy hallway, through a maze of halls. He didn’t put it past them to hit him on general principle; he was acutely aware of the armed men behind him, and acutely aware he couldn’t forecast what way their minds were running—he hatedthe way townsmen dealt with one another. You could blame practically any craziness on the fact they didn’t know, never knew, only guessed what another man wanted, or what he was about to do.

Hell of a way to live.

Meanwhile the man in the lead opened a door onto the daylight and Anveney streets.

He drew a shaky, ill-flavored breath, tucked his hands in his pockets, and amused himself, as they went out, seeking deliberate, surly eye contact with the rare passers-by, who, understandably spooked by the police armament, ducked to the other side of the street. And gawked, until they chanced into his angry stare.

Twice spooked then, they averted their eyes and found something urgent to go to.

They went halfway down the block like that, the guard in front, him in the middle, the police behind, until the guard came to what looked more like a house than an office, and showed him and their gun-carrying escort into a broad, fancy-furnished room with polished wood and fringed rugs.

Stairs went up from here, but the guard turned left. There were doors upon doors in the hall they walked. The guard led him past all of them, and through the double door at the end into a room where an overweight old man in expensive town dress sat in a green overstuffed chair roughly equal to his mass.

Smoking a pipe. God, did anybody in Anveney need more smoke?

“So,” the man said. “You’re Dale’s partner.”

First soul in Anveney that spoke sense to him, putting things like partnership in their right importance. His shoulders relaxed a little, guns or no guns, and he didn’t care all that much of a sudden that the room reeked of smokeweed.

“Stuart,” he named himself, and made a guess. “You’re Lew Cassivey.”

The man inclined his head, seeming gratified to be famous, at least to Aby Dale’s partner. Head of Cassivey & Carnell, the man Aby would risk high-country weather to keep happy—his intervening made some sense, but it didn’t guarantee his good will, or his good intentions.

“Sorry about Dale,” Cassivey said, sending up a series of short puffs. “Real sorry.”

The man wanted a reaction, Stuart realized, in a sudden new insight how deaf townsman minds had to work. The man didn’t know. He prodded. He waited to seehow he reacted.

Guil tucked his hands up under his arms, and in his best approximation of an outward reaction, shrugged and looked sorry himself. He felt the weight of the building on his back. He felt the scarcity of air. Smelled smells he couldn’t identify. < “Rogue horse,”> he said. He couldn’t stop expecting the man to see it, feel it, know it. “You heard that part.”

“I heard how she died. Couple of the riders came in with the bad news. Lost a truck and driver, too.”

“Sorry about that.” He attempted town manners, town courtesy. He wanted help. This was the man that could give it—or have him shot, directly or indirectly. “I’m on my way to Tarmin.”

“Alone?”

He shrugged, a lump of raw fear in his throat, because they’d arrived at the life-and-death points and he was feeling in the dark after reactions. “My horse. I need to get out there.”

“Hear you had a real commotion at the bank.”

What could he say? He hadn’t intended it.

But no townsman knew that if he didn’t say it.

“Didn’t mean to,” he muttered. God, he didn’t know how to talk to these people. He didn’t know what else they couldn’t guess, blind and deaf as they were. “I tried my best to calm it down.”

Cassivey seemed amused for a heartbeat, whether friendly or unfriendly amusement he couldn’t tell. The amusement died a fast death. Smoke poured out Cassivey’s nostrils. “I hear the bank gave her money to her cousin.”

“My money, too,” he said. “Everything.”

“Your money?”

“Same account. They said it was town law.”

“It’s not that simple,” Cassivey said. “But I doubt you’d want to sue.”

“Go to court?” He shook his head emphatically.

“Not if it means staying around Anveney, is that it?”

“Weather’s turning.”

“Meaning?”

“Hard to hunt.” He felt stupid, saying the obvious. He wasn’t sure it was all Cassivey was asking him. “I have to get up there. Get it before the deep snow.”

“With no help?”

“I need a gun,” he said.

“Where’s this man’s property?” Cassivey asked the guards. “Who’s got his belongings?”

“He didn’t come with any,” the one in charge said.

“No gun? No baggage?”

“Knives,” Guil said. “Two.”

“I’m paying his fine,” Cassivey said. “Somebody go get his belongings. Stuart, sit down.”

There was another chair near him, stuffed like the one Cassivey sat in. Guil put his hands on the upholstered arms and sank down gingerly, not sure how far he would sink. There was a sharp pain in his sore leg when it bent and his knees, now that he heard ‘fine’ and ‘paying’ and ‘get his belongings,’ suddenly had a disposition to wobble out of lock. The room swam and floated.

“You want a drink?” Cassivey said, as the guards cleared the room. “There’s a bottle on the table.”

“No,” he said. It wasn’t worth the risk of getting up. “Thanks.”

“You need a doctor?”

“I just want out.” His breath was shaky. He didn’t intend so much honesty. “But thanks. What do I do for you?”

“Dale was reliable. You could trust things didn’t get pilfered.” Puff. Second puff. “What’s your record on reliability?”

“Same,” he said, embarrassed to have to make claims, when he didn’t know how Cassivey should believe a man who’d come in with armed guards. “Mostly I work out of Malvey south,” he said, and not sure Cassivey was remotely interested in his explanations, he remembered how the bank had phoned. “You could phone Moss Shipping in Malvey. They know me.”

“I might do that,” Cassivey said. “Dirty trick, what Dale’s cousin did.”

He shrugged. It was. But that was his business and he didn’t answer.

“The job I have for you,” Cassivey began.

“I,” Guil interjected, fast, before the man committed too much. “I have to get up to Tarmin Height before the snow. I have to get that thing.” Maybe it was stupid. From time to time since he’d left Shamesey he’d not even been sure he cared. But the realization– the reality—of Aby’s death had made itself a cold nest in the middle of his thinking.

And she wouldn’t rest until he’d cleared Aby’s trail for her, mopped up all the loose business. Settled accounts to her satisfaction.

Which might make him lose this man’s offer, when he was indebted for a fine he couldn’t pay, with no gun, no way out. But that was the way it was; he hoped the man was reasonable. “I’m sorry,” he said, “I have to go up there. Just get me out of here. I’ll work it off for you next spring.”

Cassivey stared at him, expressionless, the pipe in his hand. Then: “Don’t turn down my offer until you’ve heard it. A commission. Enough money, supplies, whatever you need to go upcountry—the best commissions when you come to town again in the spring. Preference. Top of the list preference. What’s that worth to you?”

It was beyond generous. It was Aby’s deal with this man. It had to be.

“I still have to go up there. I have to hunt that thing. Local riders might get it. But they might not. You can’t use that road till somebody does get it. It won’t be safe.”

“I don’t argue that. You go up there, you get the horse that got her, and you do one more thing for me.”

“What’s that?”

“What kind of man is Jonas Westman?”

He didn’t expect that question of all questions. He didn’t know why Cassivey asked it. He was feeling in the dark again. And he didn’t know how to put words around the answer that a townsman would understand. He drew a breath, said what said it all. “High-country rider.”

“Honest?”

“Yeah.” There were qualifications to that. “Enough.”

“Honest as Dale was?”

He shook his head. Complicated question. He wondered just what shape of beast Cassivey was tracking with his question—or whether Cassivey in any way understood any rider. Sometimes he seemed to, and sometimes not.

“Aby liked you,” he said to Cassivey, and still didn’t know if Cassivey understood him. “Jonas Westman and his brother– they’re Hawley Antrim’s partners. Hawley’s Aby’s cousin. He’d do what Aby said, as long as she put the fear in him. So they might. On a good day.”

“Aby wouldn’t steal.”

Steal. Pilfer. Town words, for relations between townsmen and riders. Different, in a camp, among riders—where some would and some wouldn’t. “If you didn’t cheat her,” he said, “she wouldn’t steal from you.”

A pause, while Cassivey relit an evidently dead pipe. “Not even if she had a chance for real, realmoney?”

“How much?”

“Three hundred thousand. Maybe more.”

He laughed, sheer surprise—tried to think how much money that would be, and it came up ridiculous.

“What’s funny?” Cassivey asked.

Nothing, thinking of it. It was a townsman amount of money. A scary amount of money. It was an amount of money you found in banks.

And where would a rider come near that kind of money? More, what could a rider dowith it if she had it?

Cassivey sent out another puff of smoke. “The truck that went off the road?” Cassivey said. More puffs. “Gold shipment.”

Stunned comprehension. He stopped the breath he was drawing. Didn’t move for a second. Couldn’treach after the ambient, much as he wanted to. It wasn’t there.

But then, Cassivey couldn’t know what he was thinking, either. Cassivey had just told him where enough money was that rich townsmen would kill each other in droves to get it.

Enough money that a rider, if he had it stashed, could take to the roads and the hills and never work again for the rest of his life– but he’d never sleep easy about it.

“Dale knew what was on that lead truck,” Cassivey said.

Now he did. Townsmen would kill each other to know what he knew.