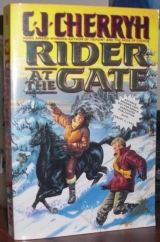

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Except that townsmen, even heavily armed, even posting guards over their sleep, and traveling with more than one truck, weren’t safe going up there into the High Wild to reach that wreckage.

Not safe from the weather.

Not safe from the rogue that could overwhelm all their defenses.

But somebody from the villages up there was inevitably going to get down to that truck. Its apparent cargo—what he’d seen in Jonas’ image—had been lumber, which wasn’t damn valuable on a forested mountainside, but just the metal in that truck had value. The engine parts. The tires and axles. Every piece of it was valuable salvage to a village. And if some village crew got to stripping it—

“Find the box,” Cassivey said. “Turn it over to the head of Tarmin Mines, at Tarmin. That’s Salmon Martines. Simple job.”

“Simple.”

“Truck went off on the downhill, on that bad turn—you know the road?”

“Seen it.” He didn’t say it he’d only seen it in Aby’s mind. Cassivey wouldn’t understand and it didn’t matter. He’d seen it in Jonas’ image. A rogue horse and that turn. Hell.

“Must be ten, fifteen trucks have gone down there.” Cassivey puffed smoke. “There, and hitting the wall at the end of the grade. Rock’s soft. Surface skids with you. Nasty, nasty turn.”

“What’s the weight?” He was suddenly in territory he knew, negotiating with a shipper, on technicalities he understood.

“More than one man can haul up a mountain. You’ll have to bring it up part at a time. Hire an ox-team and drivers at Tarmin. It’s going to take that. You ride guard on the crew, say it’s company papers you’re after, and make sure all of it gets to Martines. When the weather opens up next spring, and you’re sure you can make it down with the load, you hire that same ox-team and bring it down to Anveney. Pay’s equipment now, and a thousand in the bank. When we get that box back… I’ll drop five more thousand into your account.”

He saw why Aby had gone out of her way for this one shipper. And he knew, in one moment of revelation, whatAby had been guarding on these annual end-of-season convoys, and why Cassivey had gone out of his way to keep one honest, reliable rider very well paid.

“You’re giving me the deal she had.”

“I asked her once who else I could trust, if it ever happened she couldn’t take a convoy through.”

The air in Anveney suddenly didn’t smell half so bad. “I need a rifle. Ammunition, blanket, carry-pack, flour, oil, burning-glass… couple of sides of bacon. Got to have that.”

“You’re a very modest man, Stuart. What in hell happened to your gear?”

“No matter,” Cassivey said. “None of my business. Six hundred do it on the gear?”

“Four. She said I was honest.”

“Five. Get a pistol, too. A rifle’s not always in reach. I want you backwith my money.”

The man wasn’t just any townsman. He couldn’t be a rider. Trucker, Guil decided. Maybe a high-country miner. At least someone who’d not sat behind town walls all his life. Aby hadn’t said. Aby’d kept all her inside-buildings dealings at Anveney to herself, partly because he wasn’t interested in towns. There was just the single surface thought urging him to join her on this run. The rest—he hadn’t discussed.

This man was clearly a debt of hers. This man had asked her not to talk about his business. Somewhere, somehow, she’d owed Cassivey, in a major way. He understood it. He wondered if Cassivey did.

“Understand,” Cassivey said, “you don’t talk about what’s in that truck. You don’t talk about the thing those trucks sometimes carry.”

“Aby never talked your business to me.”

Cassivey nodded slowly. Made several slow puffs, staring at him. “A damn good woman.”

He couldn’t talk for a moment. He knew now. Aby’d not done anything out of order, hadn’t changed, hadn’t been other than the woman who’d grown up with him. Aby had pleaded with him to join her—and himself, thick-headed, he’d seen only the evasions and getting mad about it. But it was Aby. It was the woman he knew. She came back to him—dead, she came back to him the way she had been, she hadn’tlied to him, and a weight went off his back.

“Yeah,” he said finally.

“I’ll make you out a contract,” Cassivey said, and laid aside the pipe. “I’ll send someone to the bank. One fine’s enough.”

He went out with what was newly his and with a contract in his pocket, riding in the open back of a Cassivey & Carnell truck, through the main town streets and down through the town gates.

One part townsman arrogance, he’d have thought it, without having met Cassivey, to send a truck outside Anveney gates with no horse to protect it, to deliver a rider back to the Wild.

He’d have taken it as an affront to his pride and his profession– under other circumstances; points for an old trucker, scored on a rider who ordinarily would watch over anybody going a stone’s throw out past the gates of any other town.

Not at Anveney, the point surely was. At Anveney, armed guards weren’t riders, and they didn’t need help—in their grassless desolation.

Right now, with his leg hurting like unforgiven sin, he was just damned grateful that Cassivey took the trouble to save him some walking, and he was glad enough of that courtesy that he was willing to make idle conversation with the guard in the back of the truck, a guard who chattered about the weather and the coming winter and how he’d like to drive the long routes, but he wasn’t sure his wife wouldn’t take up with somebody else if he did.

So why didn’t his wife drive or ride guard in the cab? Guil wondered, and remembered—he was more practiced at it than this morning—that the guard didn’t remotely know what he wondered, no horses being near.

He was even moderately curious what the guard thought, after his experience with townsmen. He wondered to a greater extent than he ever had just what went on in townsmen minds—so much so that, on a further thought, he troubled to ask his question aloud.

“Yeah, but all those village girls… with my wife along?” the guard asked him in return, and laughed and elbowed him in the ribs as if he should understand.

But he wasn’t sure he understood the guard’s logic. He still felt dull and deaf to townsman cues… and he didn’t understand ‘wife,’ he suspected, or at least, didn’t understand Anveney expectations of wives and husbands.

But before he could ask into that odd remark, or try to figure where he and Aby had fit against that pattern in their own arrangement, they’d reached a turn-around at a fork in the dirt road.

The truck stopped, and the driver said that was as far as they were supposed to go.

So he climbed down—sore from head to foot, with a miserable headache and a spot on his temple that hurt like hell when he frowned into the evening sun. The stink was all around them, or he’d imagine it for days, and it clung to everything he’d gotten in Anveney.

But he wished them both a safe trip back, got information from them where the forks led, one to Anveney West Road—he’d thought he was right—and one to a mining pit he didn’t want to visit.

They turned around and drove off in a cloud of dust, and he slung his new-bought belongings to his shoulder and walked, a little dizzy, limping, decidedly with more load than he had the strength to carry for very long or very far.

By stages and resting a bit he could, he told himself, walk to the junction of roads and the rider stone—he didn’t know how he’d have done without the lift, but he was glad he didn’t have to try, the more so since a bank of cloud was moving in, just the gray edge advancing from off the mountains over the foothills, promising weather before dark—cold rain down here and undoubtedly snow in the high country last night, he said to himself. A cold, damp wind, blowing off the peaks of the Firgeberg, fluttered the fringes of his jacket. Its occasional gusts bent the flat brim of his hat.

Before he’d reached the next hill the temperature had dropped several degrees.

Which said he’d better hurry, as much as he could.

Various parts of him might hurt—but he hadn’t even marked down a grudge against the bank: thanks to Cassivey, who’d yanked strings on everybody including the bank, the marshal’s office, and the town judge, he’d no record of any wrongdoing, he’d been able to buy everything he remotely needed in the way of supplies, money was, by arcane townsman miracles, back in the bank, under a new number with a new card that had only his name on it and no next-of’s to enable anyone to rob him.

So Cassivey assured him, Cassivey having full confidence, Cassivey said, in the men he’d sent to make things clear to the woman at the bank. Cassivey’d paid the fine, the business was off, as townsmen called it, the books. All of which was, at the moment, more help than he’d remote interest in comprehending—if he survived the winter he’d be very interested.

But that was on the other side of winter.

He still wasn’t sure if the bank business was going to work. He personally suspected it was a way contrived for townsmen to cheat riders, and the bank still held they’d been justified in dealing Aby’s funds out to Hawley.

Which confused him—and which was the one reason he was remotely interested, right now, in what was the law with the bank. On one level he knew that he was right and that Hawley was wrong. But, town law holding to the contrary, and things having worked out in some kind of justice, by town law and townsman generosity—two words he hadn’t thought possibly fit together—it left him in enough doubt about the right and wrong of what Hawley had done that he wasn’t sure he’d even mention the transgression to Hawley, though he’d recently sworn he was going to get it out of Hawley, and then beat Hawley into horse-food.

He didn’t, now, know how much fault was Hawley’s and how much was because the bank women had suggested it to him. Hawley wasn’t damn bright in certain matters, smart enough on the trail, as far as staying alive, but he could have let his wants and what the bank told him get ahead of his common sense.

He could understand that. He knew Hawley with all his faults.

But it would still be a good idea if Hawley and both his partners were out of Shamesey before he got back next spring. It would be a good idea if they just happened to find jobs elsewhere, but on roads he traveled, for a couple of years. A couple of years might be enough to let him cool down enough, and enough to let him figure what he thought about what Hawley had done—

Right now, still damn him to bloody hell.

Damn Shamesey and Lyle Wesson, too, who could have been a lot more helpful—a lot more forward getting his belongings to him outside Shamesey gate, for one thing. Getting his belongings was why he’d gotten shot, and getting shot was why he’d not had a chance to talk to Hawley and his partners.

And Hawley and Jonas and Luke hadn’t been damn forward, either, to round up what was his and get it outside the gates, and maybe to signal there was more to tell him, and maybe, just maybe, like friends, to just camp outside the walls that night and make themselves available for talk, for errands, for whatever a man needed who wasn’t steady enough to go into the largest camp in the settled world. Put themselves out? Make themselves available?

Hell, no, they headed for the bar and warm beds.

Nobody’d been a damn lot of help, once he started adding up what certain people should have done and hadn’t. There was enough blame to go around in the situation as far as he was concerned—a lot of people in the class of riders that he wasn’t damned happy with, which was whythe business at the bank in Anveney had sunk away into cool indifference. Townsmen could be fools all they liked and you expected it. But ridershad screwed him, people he dealt with, people with a history with him, and that made him damned mad.

Only Aby…

He knew, dammit. He knew the woman and he’d been the one to fail, thinking she’d changed. He didn’t know what the debt was—he didn’t have to know. She’d have paid it. If silence was what the man asked, regarding those shipments, and she owed Cassivey—

She’d done all she could to get him into Cassivey’s employ, cajoled, pleaded. Truth be told—he’d refused to go up to Anveney for many more reasons than the smell on the money. He’d offered his own proposal: Come down to Malvey.

Why’s it always your way? he’d asked, he thought, reasonably. They’d quarreled. He’d been mad. Aby’d gone off mad—and hurt, he’d picked that up in the ambient.

But nothing of her reasons. Aby could throw that anger up like a wall. And had.

They’d thought there was forever.

But she’d owed a man. And, damn, the woman he knew never betrayed a trust. Never. Hehad.

A sudden apprehension came shivering its way through his consciousness that he’d just slipped into Aby’s last set of motions, working for the same man, following the same route—retracing, in short, everything Aby’d done down to leaving Anveney in Cassivey’s employ, exactly where Aby’d wanted him to be when they’d had their last quarrel.

So he’d just taken that job Aby had wanted him to take—more, heowed Cassivey. It was her job he inherited, her obligation, her promises.

He wasn’t superstitious like the preacher-men, but he kept thinking about that first step they kept talking about, the one on the slide to hell. He’d failed Aby; she’d have lived if he’d been there. He wouldn’t have been riding at the rear, leaving Aby on point at the worst damn turn on the mountain. He’d sent her off to partners who’d failed her. He’d sent her off to die; and maybe, in the economy of the preachers’ God, maybe he was going up where he was somehow supposed to have been in the first place.

Only this time Aby wouldn’t be there for him. Turn about was fair play.

Got her back and the woman began to bother him again.

Got her back and he had to ask—where in hell did she spend the money?

Or had she spent it? She’d never said exactly what she’d had in the account. Hecouldn’t read the damn card. No more than she could. And she’d never said.

How much did the bank giveto Hawley, anyway?

His legs wobbled. The sky went violet and brass. His shortness of breath took him by surprise. The rifle, the pistol—a winter’s ammunition, the food, all added up, considering he’d taken no few knocks. But he needed the gun. Needed the supplies. Couldn’t lay anything down.

And Burn depended on him—Burn couldn’t afford to have him go down on his face out here and freeze in the coming storm. He couldn’t bet Burn’s life that Burn would use the road to come looking for him. A nighthorse wasn’t held to roads.

He couldn’t faint out here, for Burn’s sake, he couldn’t faint and he couldn’t quit. He set his goal as the next hill down the barren road and walked that far. Then he set his intention as another hill—struggled up to its crest, telling himself now that he’d done the hard part, he could make the downhill, at least.

But his breath was short and when he looked up his blurred vision was starting to give him two barren, eroded horizons, two road-traces among doubled rocks.

His head was light. His heart began to pound. Straight line was more efficient. Wandering used up his strength faster. Had to walk straight, had to stay conscious, above all else—if he was conscious, he persuaded himself, Burn might find him; if he wasn’t, Burn might not hear him and go right by.

He walked the next uphill—and sat down at the top, in an act of prudence, to nurse his splitting headache at the road edge, rather than the middle of it, in the vague notion a truck couldcome along. Which common sense then told him wasn’t possibly going to happen again in this country until next spring, but that had been his thought when he sat down—he didn’t want to be hit by traffic.

He didn’t want to freeze, either. He could sit here till winter snows covered him, the way he felt now. The pain shot through his skull from front to back and off his temples. He squinted and it was worse.

So he rested his head on his arms and sat that way to wait for his breathing to slow down. Raw air burned his throat. He coughed and coughing hurt his head. The cold of the bare ground had numbed his feet, and the bite of the wind that swept down off the mountain wall chilled his back. He wished he’d sent Cassivey’s man after that sweater he’d seen. Rust and black one. Aby’d have liked it.

Then he must have shut his eyes for a moment—he couldn’t tell whether the sudden darkening of the land and the advent of a brassy light was the thickness of the clouds overhead or the cumulative effect of blows to the head.

He heard the sound of thunder, and thought—damn!—with the kind of sinking feeling a man got when he’d realized a serious, serious mistake.

He knew he had to move. He sat there a time more, breathing deep to gather his strength, needing to be sure he could get up and not pass out; and while he sat, a colder wind began to gust along the ridge, raising dust. He saw it coming, adjusted his hat and scarf and pulled the cuffs of the sweater he did have down over his gloves as the first fat drops spatted into the barren dust at his feet.

That was it. God had decided. He had to move. He drew a breath tinged with copper and the smell of cold rain, and put an all-out effort into getting up.

Muscles had stiffened. He used the rifle for a prop—might not have made it to his feet, he feared, without it.

He used it for a support to bend and heft the two-pack, slung its not inconsiderable weight and the rifle-strap over his shoulder. Then he started walking, heavy drops spattering the powdery dust around him, making small red craters. It felt like liquid ice where a drop found its way past the brim of his hat, down his neck or into his face.

Then—fool, he thought, remembering in the general haze of his thoughts that he’d bought a slicker—he slung the two-pack around to get at it, and had to take his gloves off.

The slicker was one of those new plastic things that didn’t hold body heat worth a damn, but he hadn’t wanted to carry the weight of canvas, especially on the climb they faced; and the thin plastic at least kept you dry, life and death in the cold seasons, when a soaking and a cold wind could freeze a man faster than he could make a shelter. Cassivey’s man had sworn it was tough—it could double as a ground sheet, and kept you drier than canvas.

If it wasn’t flapping and cracking in the gale. If your fingers didn’t freeze, finding the catches.

He had to drop the rest of the stuff to wrestle it as it snapped and fluttered in the wind, threatening escape from his numbed fingers, but he fastened latches one after the other and held it fast. It smelled worse than Anveney smokestacks, even in the gusting wind, but between that and the coat and the sweater and all, he had to own it kept the wind out. He felt warmer.

He put his gloves back on, gathered up his gear again, took the weight and walked all the way up to the top of the next hill before he ran out of breath and had to stand there leaning on the rifle and gasping and coughing.

But when he cleared the cold-weather tearing from his eyes, he saw clumps of grass around him, sparse, twisted, and brown with the season. He’d almost reached the junction with the boundary road. He was that close.

A flash of lightning blazed through his headache, blinding him, making white edges on the rocks; immediately the thunder crashed around him, total environment, deafening, pain ricocheting inside his temples and behind his eyes.

Then the rain hit in earnest, a deluge so thick it made a vapor on the blowing wind. Rain pooled in the brim of his hat and made an intermittent waterfall off the edge. He kept moving, tightening his scarf about his neck to keep the water from going down his collar. His knees were soaked below the slicker. His feet were beginning to be soaked through despite the oil coating he maintained on his boots, and the last feeling in them was going—no help at all to his balance.

Then

The whole universe opened up, a sense of location, a map of relationship to the whole landscape, and he looked uphill through the veil of rain and twilight. A dark shape was trotting toward him, brisk, angry, shaking itself as it came.

He didn’t sit down. He wanted to collapse right there in the road, his legs were so weak—but he’d only have to get up again, and be all over mud.

Burn stopped alongside him. He leaned against Burn’s rain-slick shoulder, feeling its fever-warmth against his face, with the cold rain coming down on them—stood there, Burn smelling him over and snorting in disgust, finding

Burn was warm. Burn was a windbreak. Burn was solid. Most of all, his sense of the whole world was back. Burn didn’t ask how he’d hit his head. Burn wasn’t curious about done-things, just possibly-to-do things, and if Burn’s rider was hurting, Burn was mad at the hurt and wanted it to go away. Burn wanted

He was too sick to argue. He just wanted up on Burn’s safe back and the two of them away from here and under shelter of some kind, and he didn’t think he could make the jump up—knew he couldn’t, with the two-pack. He slung the weight over Burn’s withers, wishing Burn not to object and still figuring to have an argument, with Burn in that negative mood, figuring possibly to be left in the roadway in the rain,

Burn didn’t sulk at all about the pack. Burn even dropped a leg to make it easier for a wobbly rider… but Burn’s rider couldn’t make it that way. He wanted Burn square on his feet again, and (the arm with the rifle all the way over Burn’s withers and probably jabbing him in God-knew-what places) he couldn’t do more than jump for it and land belly-down like a kid. He slithered a leg over with no grace at all, trying not to hit Burn again with the rifle barrel or knock the pack off Burn’s shoulders—he caught it, squared it, pinned it with a knee and shakily tucked the slicker about him, wet knees and all, Burn standing still as a rock the while, for which he was very grateful.

Burn slowly started moving, testing his rider’s balance. Burn’s heat reached the insides of his legs, traveling upward under the slicker, wonderful, wonderful warmth. He could hug the slicker around him and hope for the warmth below to meet the lesser warmth he’d saved in his upper body, if he could stay upright so long.

He shivered, waiting for that to happen. His legs jerking in spasm bothered Burn, whose thoughts on the matter weren’t coherent, something like

Burn figured it out, though, worried about it, and got mad, imaging

< Rider-stone, > Guil insisted, because there was a shelter where this road joined the boundary road. Intersections were places you could always look for shelter, and where there was shelter of any kind, riders set up a marker, be it wood or stone, in this otherwise desolate land, to carve or scratch over with messages to riders who came on the same road.

Burn agreed, finally, while the rain spattered about them and gullied down the hills. Burn had been waiting for him in that shelter, in a < barren, bad place, > and had only come after him when the weather turned… he already saw the refuge Burn was taking him to,

Didn’t have to say things out loud for Burn. Damn lot smarter than townsmen, Guil thought muzzily. Friendlier than bank-women.

But at least the ground cover that held out grew more frequent.

Chapter xiii

THERE WAS DAMP IN THE AIR, DAMP WHICH IN THIS UNEASY SEASON could be melting snow—or could herald another storm. The clouds which had in midafternoon wreathed the summit of Rogers Peak had moved on; and the departing sun, long slipped behind the mountains, had left a pink glow over the snowy rooftops and blued shadows along the snow-banked walls. Cookfires spread an upward smudge on the snow-blanketed evening, and the direction of that smoke said quiet winds, change pending.

“Early winter,” Tara said, on the porch of the rider quarters where, the light being better and the wind being still, she’d pulled the table outside, and she and Vadim diced potatoes for their common supper. She hashed one to bits and lost three pieces overside onto the porch. “Damn.” It wasn’t a good score she was keeping.

“I can finish,” Vadim said. “Take it easy, Tara. Go sit down.”

“I’m fine.”

“I know you’re fine. You need your fingers.”

It made her mad. It shouldn’t. She knew it shouldn’t. She chopped away, hacking at the job, trying for self-control. The horses were out of range, collectively, in the den. Flicker was ‘taking it easy.’ Flicker was sore as hell, and had earned her rest and care, having saved both their necks.

The knife slipped. She swore, sucked at a nicked finger.

“Tara, for God’s sake—”

She evaded Vadim’s attempt to see it, or to hold her, kept sucking at it. The taste of blood somehow satisfied the gnawing unease. It was real harm. You could taste it, smell it, feel it, you didn’t have to imagine it. She stood there as Vadim, with misgivings evident on his face, set back to work. For a moment, inside, the world was white. White was everywhere and her heart was pounding.

“Trust you with knives,” Vadim muttered. “I told you—”

She snapped, “I thought Barry and Llew would have started back. They ought to have started back.”

Vadim didn’t look up. A single peeling spiraled down from a potato in Vadim’s strong, capable hands. Finally Vadim said, “They’re big boys. They’ll manage the same as you did. If there’s something out there, they have as good a chance as you did. More. There’s two of them.”

“Bunch of skittery townsmen on their hands,” she said in a low voice. “Oxen. God knows what they’d do. The townsmen damn sure don’t know. There’s that wrecked truck out there. The damn convoy could have told us. Aby could have toldus.”

“They phoned.”

“From Shamesey! They let us sit here—”

“They were just four riders, that’s a big convoy, and the horses were already under attack: truck transmitters would have sent them sky high and attracted the trouble to them. God knows what else. Aby did right.”

“They could have tried somewhere on that road!”

“It might have followed them. They couldn’t lead it to a town, and it’d go straight for a transmitter. That’s thousands of people down there. If it fixed on Shamesey—they just couldn’t risk it, Tara. At least they didn’t lead it here.”

“Well, it camehere, didn’t it? God, she let us deliver a work crew out there, she let us leave Barry and Llew out there—”

“The rogue could have been anywhere on the mountain. You don’t know it was ever even near you.”

“The hell.”

“You don’t know. Unless you saw it next to you, you don’t know.”

“Well, how do you know, either? You never dealt with one. You didn’t feel what I felt out there. You didn’t even know it was out there until I got to the gate, so tell me who was close to it!”

“I don’t know,” Vadim confessed, concentrating on the potatoes, and she hadn’t meant to raise her voice. Or to say what she said. She was embarrassed.

“I’m sorry,” she muttered.

“No offense. I wasn’t out there.”

“It scared me,” she said—stupid, obvious admission she wouldn’t have made, except she regretted going at Vadim like that. “I’m still spooked.”

“Yeah,” Vadim said, “no blame from me. I’m only sorry I didn’t hear it.”

“Believe me. You aren’t sorry.”

The sending had fallen back before she got to the gate. He’d heard it only from her memory—and she didn’t want to go spreading it, recreating it, carrying it like a contagion in the camp.

Potatoes went in pieces. She was still mad. She couldn’t say why. Every nerve was raw-ended. She couldn’t stand still. She didn’t want to go down to the den, near the horses, but Flicker didn’t understand the reason for that reluctance, Flicker needed her, and she had to go down and rub down Flicker’s sore legs and try to keep a cover on her anxiousness. She’d rather peel potatoes, only she couldn’t do that right, either.

“You didn’t get any kind of shape on it,” Vadim said with a look under the brow. It was a question. Three times now, it was the same damned question. “You still don’t know if it had a rider.”

“I didn’t get any shape,” she said—snapped, and didn’t mean to. “Flicker was too strong. I told you. I couldn’t reach past her.” She’d said that over and over. But she hadn’t said, and she did say, “Truth is, I didn’t ever think of it.”

“Under the circumstances,” Vadim said. “Yeah. No question.”

Another potato went to bits under her knife. She didn’t look up. Vadim said, “Just thank God Flicker isa noisy sod. She kept it out. Whatever it was, she kept it clear of us, if it ever did come close last night.”

Come up to the walls? She hadn’t thought about that, either: her impression of distance and location of the danger behind her at the last had been so absolute she hadn’t questioned it. She’d feared it– at the gate. But everything had threatened her, then.