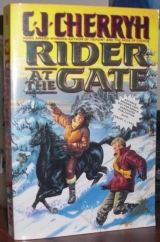

Текст книги "Rider at the Gate"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Hawley hadn’t said about the money. Though, granted, Hawley wasn’t damned bright: Aby’s mother’s half-sister must’ve screwed a post to get Hawley—he’d maintained that for years. Aby’d argued he wasn’t that dim, but, damn, he’d far undershot it. Hawley pulling what he’d pulled at the bank—God, what did you dowith a man like that? He wanted to pound Hawley’s head in right now, if only because Hawley was the easiest problem to puzzle out, and probably the one of the three with no malice: Hawley got ideas and got himself in trouble, not thinking things through, not remotely adding it up why he was going to make people mad. You wanted to beat his head in, but you didn’t somehow ever get around to doing it, because to make it worth a human being’s time, Hawley had to understand why you were mad at him—and, dammit, you had a better chance explaining morals to a lorry-lie. At least you knew where Hawley was on an issue. You could even call him honest, he was so stupid about his pilfering. Jonas, on the other hand—if Jonas was coming up here with honest intentions, meaning nothing else on his mind than paying debts to Aby, it needed more reasons than he’d ever pried out of the man. Shadow was a spooky, chancy horse, and Jonas was that kind of a man—you had to get Lukealone and a few beers along if you wanted the truth. Jonas and that horse were both spooks. In a minute and twice on a weekday, yes, Jonas would opt to keep the truth to himself. Jonas, even to his partners, especially to outsiders to that threesome, parted with information the way a townsman parted with cash money, piece at a time, and always, alwaysto Jonas’ advantage. Jonas always did his job. Letter of the contract. Depend on it. Jonas come up here out of belated remorse? Loyalty? —Friendship? Not to him. And where was Hawley, if Jonas was involved? Hell, ask Jonas what Hawley thought. Hawley always did. “Is that the riders?” Carlo wanted to know without his saying anything. “Is that Jonas? Are you warning them?” “Yeah,” he said, trying to steady down his images andhis nerves before he had to deal with Jonas. “Are they coming back?” Randy wanted to know—Randy had a sore cheek, but Randy wasn’t hurt otherwise, and Randy had maybe learned to stay away from a horse when there was something you didn’t want shouted to minds all over the area. Randy had figured a number of things out, maybe, and at least wasn’t mad at him anymore. “Yeah, they’re coming in. I don’t think Harper’s stayed around in range, or he’s real quiet out there.” He put a hand on Randy’s shoulder and squeezed, feeling the shivery excitement in Randy’s mind. “Just calm down. If you want to go around horses you have to keep it down all the time, all right?” “Yeah,” Randy said; and took a deep breath. “Are they going to shoot? Are they going to find this Harper guy?” “Just be ready to open the gate,” Danny said to the boys; he kept thinking of But “Have they found the man?” Randy asked. “The man Harper was shooting at?” “Stuart?” he said. “No, the blurry one’s probably Jonas. He’s not real noisy. They’re coming up on the gates. Be ready. They’ll come in and we shut it behind them fast as we can. Harper’s a coward. He’ll lie low if he’s outnumbered. But he could try shooting at them.” He was sending Randy handled the latch, and he and Carlo hauled at the door, moving a blanket of snow along with it. They hauled hard, making a horse-wide fan of it as Luke and then Hawley rode in, their faces stung red with cold above their scarves, snow thick on them and their horses. Then Jonas came in last and “Harper was here!” Danny said. “Harper and Quig. We shot at them.” “Explains the gunshot,” Jonas said, and slid down. “What about Stuart?” “Man’s a damn spook,” Jonas said. “Couldn’t stop him. Wouldn’t listen.” “He thinks wewere shooting at him,” Luke said. “Lit out up and over a slope somewhere—couldn’t track him in this stew.” And from Hawley, Danny thought, the more pleasant image of He didn’t want to confess how entirely stupid he’d been, but “Hit him?” “Could have. Could have hit Quig. That’s the other guy. But I’m not sure.” “You’d know,” Jonas said matter of factly, and the ambient went queasy with Snowed on. Shot at. Chased. Yelled at for a spooky fool. His feet were numb. His head hurt. Burn snorted, shook his neck, throwing off a warning to the neighborhood – a dangerously loud sending out into the ambient, considering the danger they knew was on the loose up here. But Burn always thought he owned the territory. Guil caught a fistful of mane in the middle of Burn’s neck and yanked it to distract him from challenging everything in reach. Wouldn’t really have thought it of Jonas – wouldn’t have thought that Jonas would miss, for one thing, but the snow had been blowing hard. Gust of wind, snow in the eyes… nobody was perfect. Or it couldhave been an overexcited villager, thinking that he was the rogue: spooked villagers could shoot at any damn thing they thought they saw. Could have, could have. The fact was Aby was dead and he didn’t know he was in any sense justified in his increasingly dark suspicions of Jonas – but somewhere between the headache and the ache in his leg, he was on the irrational edge of very damned mad. Give Jonas credit—he’d lay odds Hawley hadn’t run straight to inform his partners about the bank. On a day in town with the horses a long way off, even dimbrain Hawley could conceivably have done something Jonas and Luke didn’t know about. And ask where Hawley putthe funds—maybe the cold air was waking his brain up—but he bet to hellthere was another bank account. Hawley Antrim could have one. The bank women didn’t ask about brains, just if you had money. Hawley could have put most of it right back in hisaccount, right there in Anveney. And ask why Aby had used a bank at Anveney—and why Hawley knew it. She hadn’t been able to level with her partner—that was what. She’d hammered home to her partner that the account existed and he should use it. He hadn’t known—God!—that it was in event of something happening to her, as if she’d knownshe ran risks more than the ordinary. Just so casual—Use the bank, Guil. It’s safe. In the absence of her partner on her end-of-season run, she’d had to get a crew she could trust not only not to make off with the cargo but not to spill every damn thing they knew in village camps; granted there wasn’t anybody closer-mouthed or closer-minded than Jonas and Luke. Hawley—Hawley was moderately discreet because he didn’t have two thoughts a day—but he supposed, hell, he’d probably have picked Jonas and his lot himself, given Aby’s situation and Jonas showing up. Jonas in breaking the news to him had told him about the rogue, imaging just Two damn dominant males, Burn and Shadow. Burn took high offense at the mere comparison with Shadow. “Easy.” He gave a tug at Burn’s mane, set his hand on the back of Burn’s neck and shook it as Burn sucked winter air into his nostrils, God. God knew if Aby and Jonas had had anything going between them. He couldn’t imagine it. But maybe there was thatin the ambient. He’d not picked it up. He wouldn’t be offended—he didn’t think he was. Jonas was potentially more seriousthan Aby’s occasional others. But—no. He didn’t think so. Not Jonas. For the damn-all major thing—Jonas wouldn’t do it. He wouldn’t put himself that close and that off-guard to Aby’s questions. A wally-boo called. He took it for reassurance. He had the rifle slung to his shoulders, his hands stuffed into his pockets. He took one out, in the wicked gust of snow-laden wind down a fold of the mountain, to pull his breath-sodden scarf up around his nose. It was freezing with the moisture of his breath and sagging down to his mouth. He jerked it behind his head, tugged it down tight inside his collar, thinking about that sweater he could have bought in Anveney—thinking about frostbite, and asking himself whether the oil on his boots was holding out. Maybe some sense of obligation had actually gotten to Jonas, Aby having paid her life for it. Or maybe—maybe Cassivey had talked to more than one man, made a deal with more than one man regarding that cargo. Damn. Damn! That distracting notion took the trail-sense out of his legs. His foot wobbled into a hidden hole. He recovered himself a few steps, but he’d hurt the sore leg. The cold had clearly gotten to his brain. He was frozen between the consideration that maybe he ought to go back and find out what Jonas wanted—and the equally valid thought that that had been no signaling shot that had blasted bark off a tree. Jonas hadn’tfired at him when he’d chased him… Burn swung his head around and bit him above the knee, not hard, but enough to wake him up. Wasn’t fair. Wasn’t fair to weight Burn down. Didn’t dare to do it again, how-so-ever. Shaky legs had no business on a mountain. Damn near killed themselves doing it once. And there was a chance of coming down to the road a second time some distance past the shelter. A chance, if the storm worsened, of freezing to death on the mountainside. But he was limping. And speed was harder and harder. He argued, he imaged He stopped. Burn wasn’t happy, but Burn finally carried it— For a considerable distance further that even dominated But night was also coming down fast. The sunglow was leaving the sky behind the mountain wall. The temperature was dropping fast and the wind had a shriller voice as it howled among the evergreens. But a high-country shelter was, Guil swore, going to be there– ransacked like the last one or whole, he didn’t care, as long as it was whole walls, a door that would latch, and a supply of wood. Jonas would probably be after them; Jonas could show once the weather cleared and they’d talk and have some answers. They’d talk with him behind a wall with a gun-port and Jonas out in the yard telling him what the deal was with Cassivey, that was how they’d talk. But he had to get there. Had to get there. Legs had to last. Lungs had to last. As the light dimmed and dimmed, until they were walking in a murk defined by tree-shadow and the ghostly white of the clear-cut. There was ham, there was yeast bread. Danny knew how to make it, and nobody else claimed the knack. He hoped Harper could smell it out there on the wind and Harper was real, real hungry. He truly, truly hoped Stuart had made it to the next shelter. Jonas thought something he couldn’t catch. Luke had another slice of bread. “I’ll bet,” Luke said, “that Harper’s pulled back to the north-next shelter.” “Could,” Jonas said. The boys just ate their supper. There wasn’t a sign of Harper, though he thought they all kept an ear to the ambient. He ate his supper without a qualm. It was only afterward when he began to think again about He didn’t think he ought to worry. But he did. He sat in a warm spot near enough the stove it overheated his knees. He rubbed the warmth of overheated cloth into his hands, and didn’t want to move. “You think you did shoot him after all?” Carlo asked, squatting down near him. “I don’t know. I could have.” Carlo didn’t say anything else about it. Carlo was thinking about his father. About “When the snow stops,” Carlo said, “are they going to go after this Stuart guy again?” “Probably.” He rubbed his knees again. The heat was back. It was almost too uncomfortable. “What happens to you,” Carlo asked then, careful around his edges, “—if you go with a rogue and they shoot it?” “Dunno. I really don’t.” “Do they know?” A slide of Carlo’s eyes toward Jonas and the others. “I mean—” Cloud moved in, put his head on Danny’s shoulder, and Danny scratched Cloud’s chin without thinking about it. “Yeah,” Danny said. “Go to sleep,” Jonas said, and it was like a bucket of ice water on the ambient. Things just—stopped, the way old Wesson could get your attention. But it scared everybody. Cloud had jerked his head up, too, and Cloud was surly, feeling it as Jonas got up and walked over to the stove, towering over them, his face and himself half in shadow from the flue pipe. “No gain,” Jonas said, “to some questions. She could freeze. She could fall off. Could be she’s sane. Could be she isn’t. But if you get her back she won’t be the same as she was. Plain truth.” The air was cold around the fire. Just—cold. “She’s thirteen,” Carlo said in a shaky voice. “She’s just thirteen.” “Horse can’t count,” Jonas said. “Rogue doesn’t care, mountain doesn’t care. Storm out there doesn’t care. And we won’t know.” “Ease off him,” Danny said. “Jonas, it’s their sister, for God’s sake.” “No difference.” “Maybe riders get dropped under a damn bush, but village kids come with sisters, Jonas—sisters and brothers and Didn’t know who that was. Jonas all of a sudden flared up—was just “Clean up,” Jonas said. “The hell. Youclean up. I cooked it.” Horses were “Hawley,” Jonas said. “You want to pick up the site?” “Yeah,” Hawley said, and the air was quieter. Carlo had gone tense. Randy was stiff and scared-looking, huddled against him. Danny felt a flutter in his heart and got up from where he was sitting, went over and calmed Cloud down, trying not to think real-time, thinking about But papa never got his fingernails clean, never bothered too much because it was back to the shop after supper. Papa worked real hard. That last was Carlo. It was Randy, too. They’d gotten up. They came over to join him, still The ambient grew quieter and quieter, as if the whole world was freezing. Even the hardier creatures on the mountain had sought shelter from the storm, and the nightly predators had evidently decided on a night to stay snug in their burrows. There was a time you thought you had to give it up and try to tuck in somewhere, and if you didn’t, you somehow kept going. And after you were mind-numb and still walking on that last decision there came a time the body kept working and the brain utterly quit: Guil caught himself walking without looking, a second after he slid on a buried rut and had the bad leg go sideways. Burn just forged ahead. The leg could be broken, for all Guil could feel—it was numb from toes to knee, the knees and ankles were going, and Burn, damn him, just kept on plowing through the snow. <“ Burn!”> he yelled, straining a throat raw with cold, thin air. That started him coughing, and still Burn didn’t stop. It was a betrayal he’d never in his life expected. Burn had never left him. Females, maybe, delusions of females—only thing that he knew would distract Burn to that extent. Then: He got up, he slogged ahead in the trail Burn broke for him. He stumbled and he used the rifle for help staying on his feet, but, damn, it was there, it was solid in the dark, he could see it with his own eyes, tears freezing his lashes and his lids half-shut. Burn was a “Hell, Burn, you’ll ice it breathing on it, you fool—” He could hardly talk, but he set the rifle against the wall and squeezed up beside Burn, got a grip with stiff, gloved fingers on the latch chain, and pulled. The latch lifted. Getting a snowbound door was a matter of kicking the snow clear and the ice clear, getting a grip on the handle and pulling the door so you had a crack to get your hands into. Another tug outward and Burn got his jaw into the act, stuck just his chin through the door and started pulling back, working his head in and forcing it wider. Outward-opening. Always outward opening, all the shelters. You had a snow door, even a roof trap you could use if the snow piled up and you had to, but outward gave you better protection against spook-bears, who always pushed and dug. “Come on, Burn, Burn, give me some room, you fool, it’s still blocked—” Ice broke. It moved, and Burn wasn’t taking any nonsense. Burn got a shoulder in, and more ice broke—Burn’s rider’s foot was a narrow miss as Burn shoved his way in with thoughts of Clean shelter. No vermin. Nothing moved in the dark inside. He had an idea how the locals set things up now. He retrieved the rifle, got the door shut—pulled his right-hand glove off with his teeth and put his fingers in his mouth to warm them. They hurt, God, they hurt so much tears started in his eyes and added to those frozen to his eyelashes. Burn came and breathed on him, that was some help when the shakes started, enough that he was able to get into his pocket and get the waxed matches. He got one lit—the thumbnail still worked, even if he couldn’t feel the thumb. Better yet, he was able to hold onto the match as it flared and showed him a cabin like any rider shelter—showed him the mantel, and besides a charred slow-match, a lantern with the wick ready and the chimney set beside it. He lit it on one match, blinked the tears from his eyes and felt that one little flame as a blazing warmth in a world gone all to ice and wind. The fire was laid and ready. He lit the slow-match from the lantern, lit the fire from the match, and squatted there fanning it with his hat until he was sure beyond a doubt he had it going. The wind was all the while moaning around the eaves like a living thing and thumping down the chimney. He chose to take a little smoke until the fire was strong enough for the snow-dump that sometimes came when you opened the flue—there was almost certainly a snow-shield on the chimney, but when he finally pulled the chain, he still got ice. It plummeted onto the logs, hissed, and knocked some of the inner structure flat. It didn’t kill the fire, only flung out a white dusting of ash. He stayed there in the warmth and light with Burn going about sniffing this and that—he pulled off his left glove and checked his fingers over for frostbite—felt over his face and his ears, which were starting to hurt, with fingers possibly in worse condition. But he wasn’t the only one cold and miserable. He put his fire-warmed gloves back on, wincing with the pain, wrapped a scarf around his head and, taking a wooden pail from the corner, cracked the door to get snow from outside, packed it down with his fists and came back to the fire to melt it. While he waited for that, he delved into the two-pack and got out the strong-smelling salve that by some miracle or its pungent content wasn’t frozen solid. Burn was amenable to a rub-down, even if it took precedence over bacon, and Guil peeled out of his coat, called Burn over near the fire and rubbed on salve barehanded, chafed and rubbed until he’d broken a sweat himself, despite the cold walls and floor. Burn was certainly more comfortable. Both of them were warmer. He thought his fingers might survive. He pulled off his boots and the cold socks, and applied the stinging salve to his feet, relieved to find the boots hadn’t soaked through, that feeling was coming back, at least an awareness of his feet, and a keen pain above the ankles. He wasn’t altogether sure he hadn’t gotten frostbite. Couldn’t tell, yet. And the toes wouldn’t move. Couldn’t afford to go through life with unsound feet. God, oh, God, he couldn’t—limping along on the short routes where the horse could do all the walking. He didn’t want that for a future. He was more worried about his feet than about gunfire—so anxious that Burn in all sympathy came over and breathed on his feet, licked them, once, but the salve tasted too bad. He’d have been safer and smarter, he thought now, to have camped in the open. He’d have been warmer sooner. A blizzard like this could pile up snow in drifts high as a shelter roof—it might not let up with morning or even next evening. The wind screamed across the roof—there was a loose shingle up there or a flashing or something that wailed a single rising and falling note on the gusts, a note you either ignored or let drive you crazy; but he was so glad of warm shelter tonight he told himself it was music. Burn made another try at his feet. Burn was half-frozen and had a fearsome empty spot inside. “Hell,” Guil moaned, and crawled over, stretched out an arm as far as he could reach and dragged the pack up close—fed Burn and himself jerky and a couple of sticky grain sweets, the kind he kept for moments like this, except his mouth and Burn’s had been too dry too long out there, and Burn’s throat was too raw, his tongue too dry to enjoy it. But maybe, maybe there was a little bit of feeling in his feet. He tried moving his toes. Couldn’t quite get all of them to work, but some did that hadn’t—and finally, finally, he got movement out of them all. Guil sighed then, with vast relief—took a pan out, thinking of other comforts, took his knife to thoroughly frozen bacon, having to lean on the blade to get through it. There was water, finally. There was oil for biscuits—Burn got the bacon squares; he nipped a couple for himself. By then his feet and hands had begun to hurt. Really hurt. But the toes wiggled quite nicely, and he sat there content to watch that painful miracle while the biscuits nearly burned. Meanwhile Burn, with water to drink and with the ambient a lot less They disappeared without hesitation. He made more, got one for himself out of the next pan. Burn got six. He found he hadn’t as much appetite as he had thought—but before he lay down he stood up, hobbled painfully over to the door and pulled the latch-cord in to protect their sleep. Then he stirred up more biscuits for the morning, put them on to bake over the coals; and after what felt like a second, Burn had to wake him up off the warm stones to get him to take them out. Burn knew He ate one more biscuit then, put the rest by, and in shaky self-indulgence, made hot tea, assured now his teeth wouldn’t crack if he drank it. Among his Anveney purchases was a little metal flask of spirits, for steeping medicines, as he intended, not the luxury of drink. But the shelter came, courtesy of the maintenance crews, for which he blessed their kindness—equipped with a bottle on the mantel, and he poured about a third spirits into his second cup of tea; sipped it ever so slowly, letting it seep into dry mouth and dry throat and burn all the way down. It was the first time he’d looked at the rider board, up above the mantel. His heart nearly stopped. Some not-so-bad artist had filled a large area of the board with a horse head, all jagged teeth, staring eyes, wild mane, ears flat to the skull. Rogue horse. A warning to anybody who came here. And he knew the sketch artist beyond a doubt when he saw, above it, the mark that was Jonas Westman. Jonas had been in this place, on his way to Tarmin, Jonas and his partners—sitting here where he sat. They’d laid the fire he’d used. Made that ghastly image. But that wasn’t the total source of disturbance. He was feeling something—faint, dim sense of presence. –Something in the ambient, no image brushing the surface of his thoughts, just a whisper of life outside the shelter that sent his hand reaching for the rifle. It had Burn’s attention, too—head up, ears up, nostrils flared, as he stared toward the door. But the sending didn’t seem to come from several horses. It wasn’t strong, it wasn’t loud and it shifted and eluded his conception of it, at times completely disappearing. Shadow could feel that way—alone. But Shadow wouldn’t bealone. And he wasn’t sure what it was. He wasn’t sure it wasn’t some passing cat—but no cat in its right mind would be out in a blizzard.