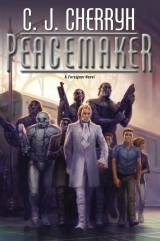

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

But Gene just went on frowning, and it was not right, and nothing could make it right. Gene was the one who always measured shares of the food he brought, so they were exactly right. Exactly right, not a crumb off equal—because it mattered to Gene.

And here they were, measuring again, only there was no way for it ever to come out even.

Fair, Gene would say. And it was one of the strongest things about Gene. He always was . . . fair. But sometimes you had to argue with him. And sometimes it was as if he knew Gene best of all of them.

“Hey,” he said, that word that meant listen, and he laid a hand on his chest, the way he had done when they had first met in the ship corridors, almost the first children he had ever seen. And they’d stared at each other. He said, solemnly, as he’d said then: “Cajeiri. I’m Cajeiri.”

Usually it was Irene that understood language things first, but not this time. “Gene!” Gene said staunchly, with the same solemn gesture. And Gene swept a gesture at Irene and Artur. “Irene. Artur. Human.”

“Ateva,” he said. It was their first meeting all over again. “No change!”

“No change,” Gene said. “No change, us.”

“Friends,” Cajeiri said in ship-speak, right across the room from Madam Saidin and Master Kusha and his own valets and everybody. “And,” he said in Ragi, “I can give you gifts for my birthday, if I want! Adults do. So I can. This is how atevi do. Yes?”

Gene gave a nervous smile. They all did, and touched hands the way ship-humans did, then laughed.

“Friends,” Artur said, and Irene, who followed the rules most of the time, said, “We’re not supposed to say that, you know.”

“We still can,” Cajeiri said, and added somberly, because it was always true: “until we grow up.”

11

The tea service went around at its own deliberate pace, deliberately drunk, during which the mind had ample opportunity to race, and there was no light conversation, only a meditative pause.

“How is my son,” was Tabini’s belated question, “in your view, paidhi?”

“Very well, aiji-ma,” Bren said. “I have inquired. He continues as unaffected and as uninvolved as we can manage.”

“A wonder in itself,” Tabini said darkly. He set his teacup down quietly on the side table. Bren set his down scarcely touched. So with all of them, immediately.

“You and your aishid intend to enter Assassins’ Guild Headquarters,” Tabini said, “bearing an order of mine, with the intent to enter it in Council records. You intend to provide access for an assassination of the consort’s elder kinsman and the forcible seizure of Guild records.”

“Yes, aiji-ma. One hopes you will lend your seal to such a document.”

“One understands that this is not conceived as a suicide mission.”

“One hopes it will not be, aiji-ma.”

“We have also had it suggested,” Tabini said grimly, “that this document—with many and conspicuous seals—be an official inquiry into the Dojisigi situation—for official purposes.”

Bren gave a single nod. “The Guild Council will likely be dealing with the Kadagidi matter, aiji-ma. One believes the Dojisigi matter will be unexpected.”

“To throw the Assassins’ Guild off its balance?” Tabini asked with the arch of a brow, and just then Cenedi put a finger to his left ear, atop that discreet earpiece, frowning as he did so.

“The aiji-dowager,” Cenedi said, “is on her way.”

“Gods less fortunate!” Tabini hissed, and cast a look at Cenedi, but Cenedi’s face remained impassive. One doubted that Cenedi or Nawari, apparently having been in conference with Tabini, had yet had time to break the news to Ilisidi that the paidhi-aiji was going on this venture and she was not. But there were a number of the dowager’s staff serving in Tabini’s apartment, who might have found a way to know about the request for the document, and who might have relayed the information. There was a broad choice.

“I declined the aiji-dowager’s request to come to her for a conference not half an hour ago,” Bren said quietly, not going so far as a complete denial of responsibility, “since I was about to come to speak to you, aiji-ma. Then Cenedi intervened with the news that you were coming to visit me.”

“Oh, we have no question,” Tabini said. “We do not ask. We do not need to ask how my grandmother keeps herself informed, granted her staff is our staff.” A deep breath. “Nand’ paidhi, this mission is your request?”

“One certainly cannot permit the aiji-dowager to undertake it herself, aiji-ma.”

Tabini gave a short, sharp laugh. “One cannot permit! If you are able to deny my grandmother anything she has set her mind to do, paidhi-ji, you surpass my skills.” And soberly: “I am not willing to lose you, paidhi. Bear that in mind. Do not decide to protect your aishid. I know you. Do not do it!”

He could feel his bodyguard seconding that order.

“One will be cautious, aiji-ma.”

“Cautious! Caution has nothing to do with your decision to take this on.” A deep breath. “But you are right: you are the logical one to undertake this. There is no combination of Guild force more effective that we can bring within those doors, than the combination in this room. And I do understand your strategy—having this document regard the Dojisigi matter. Clever. I shall write your document—it will take me far less than an hour—and set the seals of various departments on it. But I hope the cleverness of your choice of documents will not have to come into play. To that end, and in that spirit– Take this.” He pulled off the massive seal ring he wore on his third finger, and proffered it.

No human in history had ever borne that object.

Bren rose. One did not ask even Banichi to handle that seal. He took it personally, and bowed, deeply. “Aiji-ma.”

“This seal I need not affix. I send it with you. If they refuse that at the doors, they will be in violation of their own charter, and on that refusal alone, I can bring the legislature against them—but one fears any delay will give them time to destroy documents, and one does not even mention the threat to you. One hopes this will get you all out unscathed.”

“One is grateful, aiji-ma.” Bren settled back into his chair, and slipped the ring on. It was too large even for his index finger. He had to close his hand on it. “But should something happen—you will have every legal grounds the legislature could ask.” He held up the fist with the ring. “This will not see disrespect.”

“We assure the aiji,” Banichi said, “if they disrespect your authority, those doors still will open tonight.”

“Besides the Office of Assignments,” Cenedi said quietly, “be it known, aiji-ma, nand’ paidhi, that we have two problems within the Guild Council, and one more presiding whose qualifications to preside over Council are questionable. Those three will need to resign. We shall make that clear.” Cenedi, standing near the door, walked closer and into Tabini’s convenient view. “The names of the problems, aiji-ma: the one you know. Ditema of the Paigeni.”

“Him. Good riddance.”

“Add Segita of the Remiandi.”

“We do not know him.”

“They are both senior. They came in after the coup. They have conservative views which are, themselves, not in question; but their support of the Office of Assignments has repeatedly, since your return, blunted all attempts to insist that Assignments should operate under normal rules and create an orderly and modern filing system. One interpretation is that they have felt a certain sympathy for a long-lived institution of the Guild, and they have innocently made it easier for Assignments to misbehave. Another interpretation is less forgiving. Their age and rank have completely overawed the less qualified members that currently fill out the rest of the body, and no one stands up to these two voices. They have pressed the matter of non-returning Guild. We, on the other hand have appealed to certain retired members to come back to active duty, and they have agreed to do so. This would include eight of the old Council . . .”

“Not Daimano,” Tabini said.

“She would be in that number,” Cenedi said. “She is, in fact, critical to the plan, aiji-ma. If you support her return, three others will come, among them two other very elder Guild members that we most need in the governing seats. You know who.”

“Gods less fortunate,” Tabini muttered.

“Daimano is an able administrator. And whatever else she ever was, she is no ally of Murini.”

Tabini gave a wave of his hand. “We do not interfere in Guild politics. If the Guild elects her—may she live long and do as she pleases. Not that I offer any speculation at all on the Council’s composition, nor shall ever officially remember these names.”

“I shall relay that, aiji-ma,” Cenedi said.

“Key to the old Guild, you say.”

“She stood by you during Murini’s regime, aiji-ma. She, in fact, directed the entire eastern network, when Prijado died.”

“Then we owe her gratitude for that, though one is certain it was reluctant. We shall owe her for this, if she can bring order.”

“Order,” Cenedi said dryly, “is certainly one thing that will result from her administration.”

“Not to mention needing a decade of hearings to get a simple document issued. Forests are in danger, considering the paper consumption with this woman in office.”

“We shall argue for computers in Assignments and Records, aiji-ma. We have had ample example of pen and ink filing systems. She wants to take the Assignments post for a year, at least, to supervise its operation, and to have the records under her hand.”

“Gods less fortunate. So be—”

There was a distant sharp report, the impact of brass on ancient stone, right outside the apartment. And a subsequent rap at the outer door.

“She is here,” Cenedi said, not regarding the woman under current discussion. Cenedi drew a deep breath, and added: “Aiji-ma, regarding the Guild Council, and Daimano, we shall deal with the difficulties.”

“Let her in, paidhi,” Tabini said, and Bren nodded to Banichi, who said something inaudible, short-range.

The outer door had already opened, and one could hear the advancing tap of the dowager’s brass-capped cane on terrazzo and on the foyer carpet as she passed the door. With that came the footsteps of her attendant bodyguard.

“The aiji is in the sitting room with nand’ Bren,” Bren heard Jeladi say, out in the foyer, and heard the arrival head their way with scarcely a pause. Tap. Tap. Tap.

Jeladi opened the door and stood out of the way.

“Well!” Ilisidi said, arriving in the room with two of her indefinite number of bodyguards—staff hastened to move in a suitable chair appropriately angled, beside Tabini, and two more, beyond hers. “Well!”

She sat down, upright, with the cane in hand beside the chair arm. It was Casimi and his partner Seimaji who had escorted her in. Seimaji moved quietly to take a chair at her right hand, while Cenedi and Nawari stayed where they sat, somewhat facing her.

“The document!” she said sharply, with a wave of her left hand.

Casimi, not yet seated, proffered to Tabini the rolled parchment he carried, a large one with abundant red and black ribbons attached. Nawari rose and took it, serving as Tabini’s staff for the moment.

“That is,” Ilisidi said, “for your use, Grandson, if you are still in process of formulating a cause to take before the Guild Council.”

Tabini shot out a hand. Nawari passed it to him, and Tabini scanned the parchment, frowning.

“The paidhi-aiji has wanted a document about the southern situation.”

“Read on. It covers that matter. Abundantly.”

“What have you done with the two Dojisigi?” Tabini asked, reading on.

“Why, fed them, housed them, like any good host. I have requested them to stay politely to quarters and answer any questions we may have at any hour. Meanwhile, since the day before yesterday midnight we have liberated a Marid village from scoundrels, defused a bomb, dislodged a traitor from a lordship, taken down a Shadow Guild leader in the Marid, and brought your son safely home. What else should we do?” Ilisidi waggled her fingers, and Casimi produced a second ribboned and sealed parchment from inside his jacket. “This deposition, to be placed in evidence at the appropriate time, is signed, and witnessed. You may find it interesting reading—a detailed account of the actions of the Guild officers in charge of the Dojisigin Marid, how the local Guild were disarmed, how they were kept under arrest, then released and sent out as protection for their respective villages, units split apart, and most of all, sent into problem districts without so much as sidearms. These two were split from the other team of their unit, whose whereabouts we do not know even to this hour, nor what orders they may have been given, nor what hostages may be at stake. These two in our custody have asked permission to go south to find their partners. We have denied that, but we have warned Lord Machigi . . . who is one likely target of any second Dojisigi-based operation, and we have personally requested him to negotiate a bloodless surrender of the partners of these men should they come into his territory. We will urge Machigi to make a public statement of what happened in the Dojisigin Marid once our operation tonight goes forward.”

“I have no criticism of the plan,” Tabini said, passing the documents to Cenedi. “Well done, honored Grandmother.”

Everything was amazingly amicable. Bren almost began to relax.

“It is, however, an underhanded business,” Ilisidi said, her long fingers extending, then clamping like a vise on the head of the cane she had beside her, “an underhanded business, Grandson, first to thrust off on your ailing grandmother a flight of human children, asking me to extend my security to guard the East and the north, with precious little assistance—”

“I sent you the Taibeni!” Tabini retorted, voice rising. “What more do you want? My house guard? No? Of course not! They are already yours!”

“Aijiin-ma,” Bren said quietly, unheard.

“I have my own bodyguard fully extended,” Ilisidi retorted, “watching your residence, guarding Lord Aseida and two Dojisigi Assassins, and assisting Lord Tatiseigi, who has gallantly opened a household filled with delicate antiquities to host your son—”

“Your great-grandson, who has had as much of your rearing as mine! And he is Lord Tatiseigi’s own grand-nephew! If the lad with your teaching cannot manage the situation—”

“And three human guests who cannot even perceive a warning!”

“You were supervising him when he routinely ran the halls of the ship unguarded, held clandestine meetings with the offspring of prisoners who had all but started a war in the heavens, a population who had to be forcibly removed from that place, and who to this day present a problem on the station! If you had prevented his association with these children in the first place, we would not have human guests in the middle of this crisis!”

“And you would not have a son well-acquainted with factions and powers in the heavens as well as the aishidi’tat! The boy has become an asset to the aishidi’tat, educated in all the politics that may foreseeably affect us! The boy has influence and alliances many a lord of the aishidi’tat would covet! Do you wish to pass blame for this situation? I shall not hesitate to claim responsibility for it!”

“His attachment is inconvenient, at the moment!”

“When is it ever convenient? Your years and mine pass at one speed—but the boy? His years race toward a new age, his age, in which he will face decisions without the benefit of your father’s bad example—”

“Do not call upon my father for an example! And while we are praising the efficacy of your teaching, my father was all your handiwork!”

“Back away from that brink, grandson! My son had his father for an example! He had flatterers at his ear whom his father allowed in court! And he had the same damnable, wilful temper! I have no idea where you acquired it, if not from your grandfather! It passes in the blood, I suspect, and is none of mine!”

“You have no temper? Ha!”

“Aijiin-ma!” Bren said. “One would treasure the thought of unanimity in an undertaking, unanimity, and harmonious good wishes.”

“See?” Ilisidi said. “Harmony. There is a word for you, Grandson. Can we manage harmony, in the few hours before the paidhi undertakes a great risk in our names?”

Tabini’s nostrils flared. His scowl did not much diminish, but his voice was quieter. “We have been informed of as much as we wish to know, and we greatly mourn our lost aishid at this moment. These young men who serve us now have all the will and courage one could ask, but have not yet acquired the skills or the rank to undertake a challenge to the Guild. And the risk we run in this operation is life and death, nothing less, not alone for the paidhi-aiji.”

“Not for him alone,” Ilisidi said. “But we have a plan.”

“We are sure you have a plan,” Tabini said, “and that we are about to hear it.”

“We have unexpected assets,” Ilisidi said, “which will not, perhaps, surprise our enemies, since the events at Asien’dalun, but arms which will protect these foreign guests, and your son, and the rest of us while these things are underway, and in any attempt at a second coup. Bren-paidhi, do you concur? More to the point, does he?”

Jase. Jase, who had surfaced only briefly this morning to confer with him, and who had graciously informed Narani he and his bodyguard would rest and allow the household to rest—unless the young gentleman needed them. And who had already taken the responsibility the dowager asked.

“Jase-aiji does concur,” Bren said. “He understands the risk, and I already have his promise. No hostile operation can reach this floor with his bodyguard in place. One cannot swear to the safety of the entire building, but the safety of the persons on this floor—yes, aijiin-ma. This Jase-aiji has told me: he can contact the station without going through the Messengers’ Guild, and if Lord Geigi were advised that you, aijiin-ma, or the young gentleman, his guests, or the spaceport itself were threatened with any harm, we all know Lord Geigi has the means and the will to act. Lord Geigi has, nand’ Jase informs me, considerably fortified the spaceport in this last year. And should any violence overtake you, aiji-ma, Jase-aiji would immediately move to your defense. It would be a very foolish act to attack here in the Bujavid.”

“A foolish act, or an entirely desperate one,” Tabini said. “And should they have any such notions and find themselves countered, they may well become desperate.”

“Jase-aiji’s weapons can defend you. More, he will get you and the aiji-dowager and your son to safety at the port . . . should there be need.” He saw Tabini take in a breath. “Please accept this idea, aiji-ma. Preserve yourself. We cannot have these bandits in charge again. The aishidi’tat cannot suffer this again. Rely on Jase-aiji. You will be constantly in the network, and in charge of it, at all points. Communication between the station and the ground will not depend on any system they can possibly cut off, and you can rely on Geigi to carry out your orders.”

“We have discussed the resources of the heavens. We have discussed it with Lord Geigi. I have prepared orders, honored Grandmother, which will—just as a formality, since we believe you could bully your way through on any day you chose—put the Bujavid guard and the transport station and the spaceport under your control—should anything befall me.”

Ilisidi raised an eyebrow and nodded somberly. “Then we should accept those orders. On the other hand, if we are not permitted to be foolish, neither are you, grandson. The paidhi’s plan involves, one takes it, reaching the spaceport.”

“My own plan consists in not replicating the mistakes of the last incident,” Tabini said. “Reaching the spaceport, yes. And holding it. And its communications.”

Getting off the planet, Bren thought, but he had no intention of arguing with Tabini at this stage. If Tabini just agreed to get that far—with Jase—they had everything they needed. “One is grateful for your agreement,” he said.

“We shall not be caught by surprise, paidhi,” Tabini said. “And you are not to die.”

Bren inclined his head. “One will do one’s best, aiji-ma.”

“Give us back the Guild,” Tabini said. “Give us that one resource, and this firestorm over the Kadagidi and the Ajuri will evaporate in the morning sunlight.”

The legislature was in session. The enemy’s rumors about the Kadagidi situation would have traveled. One could only imagine.

Would it all evaporate? He was less sure.

“They can stew,” Ilisidi said with a wave of her jeweled fingers. “Would we had shot that fool Aseida outright.”

“Would that someone had, long since,” Tabini said, and set his hands on his knees, preparatory to rising. “However, honored Grandmother, you will decline to dine with your guests this evening. You will attend my table tonight, so Cenedi informs me.”

His own aishid’s plan. Guard the aiji. Get their problems into one defensible spot. The aiji’s apartment lacked the servant passages that made other apartments a security sieve. Get them all into the aiji’s premises and set Jase and Jase’s guard to hold it—while they provoked all hell to break loose.

Ilisidi arched a brow. “Dinner, is it?”

“The party will include the young gentleman, his host, his guests, and the ship-aiji, so we are already informed. The paidhi-aiji is invited, of course, as a courtesy, but we understand he has a prior engagement. Now we know what that engagement is.”

“Aiji-ma.” Bren gave a little, seated bow, then rose as the others rose, and bowed a second time. Tabini had agreed. Jago had prompted him to ask what he had asked of Jase. Cenedi had argued out what they needed from Tabini. Their bodyguards had nudged the pieces into place.

Now the dowager had agreed.

It was done. Arranged. And the action was underway.

In that moment of realization Bren had a little twinge of panic—a sense of mortality. Fear—maybe, at how very fast things were moving. But he refused to entertain it: there was no time for second thoughts. He bowed, saw his guests to the foyer, and watched Tabini depart.

He felt, then, the dowager’s hand on his arm. It closed with startling force. “Do not lose,” Ilisidi said, and walked out.

· · ·

“I have one fancy coat,” Jase said, “for the formal party. Should I wear that to the aiji’s dinner?”

“God. No. You can’t wear it to both. Borrow one of mine,” Bren said. “My staff will see to it. Brown, blue, or green?”

“Blue.” Jase’s own formal uniform was blue. “Moral reinforcement.”

“Your bodyguard will be in armor all evening, until God knows when, maybe into morning. Sorry for them. Staff will see they get fed.”

“No question they’ll be in armor,” Jase said, “and all of us will be hoping like hell we won’t need it. They’ll appreciate the food. Especially the pickle, apparently.”

“God, humans that like the pickle.”

“They seem to.”

“Amazing. Enjoy your dinner this evening. Watch the exchanges between Ilisidi and Damiri—the dowager’s going to be on a hair trigger. Damiri’s going to be operating with a sure knowledge something’s going on and I’m not sure anybody’s telling her anything. She’s going to be upset. Cajeiri’s going to be nervous. Most of all keep all the youngsters low key and don’t let them get scared.”

Jase exhaled a short breath. “I’ll be hoping to hold dinner down.”

“Calm. Easy. It’ll all work. That link to Geigi . . . if you can assure me that’s going to be infallible and available from inside the Bujavid, I’ll be a lot happier this evening.”

“I won’t tell you how. But, yes, rely on it.”

· · ·

It was court dress for the paidhi-aiji, no less, the best, a leather briefcase to hold the relevant documents with their wax seals and trailing ribbons, and, this time, no small pistol in his pocket. Bulletproof vests or the like were standard with the Guild itself—it was no problem, Jago told him, for him to take that precaution. But a firearm on his person was not in the plan. Innocence. Absolute innocence was what he had to maintain. There were detectors near the door.

He was nervous as he dressed. He tried not to be. He had to sit or stand while his valets worked, and he found himself disposed to glance about, thinking—I might not be back here again. He caught himself on that one—bore down instead on recalling the image of Assassins’ Guild Headquarters, and the floor plan his bodyguard had drawn for him, where the guards would be, and what they had to do in this or that case.

A rail spur ran through the cobbled plaza around which the various guilds clustered. It was an antique line, a track used these days for six regular trains from the old station, four freight runs for the uptown shops and a twice-daily local for office workers in the district. The area saw mostly van and small bus traffic, few pedestrians, except Guild members going to a few local restaurants or to the two sheltered stops, since there were no other businesses nor residences in the area.

They would have someone in place to shunt the train off onto that spur, and that would get them into the plaza.

That part had to work. The train would reach a certain point—and stop, not at a boarding point.

There were sixty-one paces from a certain lamp post to the steps of the Assassins’ Guild, seven shallow steps up to the doors that had to open, and beyond that, three taller steps up to a hall that held all the administrative offices which ordinary non-Guild might ever have reason to visit—prospective clients might have business there; witnesses called in particular cases might give depositions there.

Each of those nine offices had a door and small foyer, each outer door being half hammered glass, the inner generally a full panel of the same.

Each office also had a service entry in the rear, onto a hidden corridor. Those could pose a problem.

Each office was staffed with lightly armed Guild clerical personnel, but they were visited, occasionally, by regular Guild on business, who might pose a more serious threat.

The hall reached a guarded door at the end, a single door that divided the public from the one other Guild section that was ever available to outsiders—the Guild Council.

There was, slight problem, a hall intersecting the left of that door, a short side hallway of six offices, which came to a dead end at the wall masking the service corridor.

That guarded door at the end of the public-access hall opened onto a wider area with a jog to the left, a short continuation of the main hall, and the double doors of the Guild Council chamber at its end. Those double doors were guarded whenever the Council was in session. To the right of anyone coming into that broad quasi-foyer was a wall with a bench, and to the left was a wooden door that stayed locked: that was the administrative corridor, where even high-ranking visitors did not go, and that was Cenedi’s problem.

The Council Chamber, those guarded double doors in that offset stub of the main hallway, that was their target—as far as they could get toward it . . . or into it if everything worked well.

Arrangements, contingencies, branching instructions, if this, then that, meeting points, timing, nooks in the public hall that might afford protection at some angles if they were stalled and under attack . . . nooks that were no decorative accident, but designed with defense in mind, equally apt to be used by those attacking them: there was one angle, which the guards at the second, single door, commanded, that had a vantage on all three of those spots. . . .

He had never been so deeply involved in the details of a technical operation. They’d taken a space station with less worry.

And he only knew their part of it. Cenedi would be in that administrative hallway next to the Council chamber, conducting the dowager’s business. Cenedi was the one of them able to get close to the Office of Assignments. Cenedi had the seniority to start with minor business at some minor office in the administrative section and get into that critical hallway on his own . . . they hoped.

And somewhere involved in all this were other persons who were, Jago had said, in the city, and keeping a very low profile. That group had heavier arms. They would be moving, somehow, somewhere. Jago hadn’t said and he hadn’t asked.

But once that contingent arrived—he could figure that part for himself—that outer hallway wasn’t a good place to be. Court dress was going to stand out like a beacon wherever he was, as if a fair-haired human didn’t, on his own. In a certain sense that fair hair and light skin was a protection: honest Guildsmen would try not to shoot a court official . . . but the Shadow Guild, granted that Assignments had his own agents inside Guild Headquarters, would definitely aim at him above all others. And that part he really didn’t want to think about in detail. Not at all.

· · ·

Cajeiri was in the good coat he had traveled in. Everybody was dressed as best they could, scrubbed and anxious, in such ready-made clothes as Master Kusha had left with Great-uncle’s staff, with an assistant’s instructions to shorten a sleeve or let out a seam or add a little lace: Master Kusha had left the material for that, too. And it was not the fine brocade of their festivity dress, which Master Kusha had taken away with him, but they were presentably fashionable and the clothes were pressed and clean, which was as good as they could manage until Master Kusha sent back the others—because their baggage had not come in yet, and they had a formal family supper to attend.

Irene was the only one whose hair could manage an almost proper queue—but what ribbon the guests should wear had been a question for Madam Saidin, who had lent her one of her own, a quiet brown that was not of any particular house, and on Irene’s pale hair and Artur’s red, and against Gene’s dark brown, it stood out like a bright color.

His aishid was likewise lacking their best uniforms; but their black leather was polished, the best they could do. Everybody was the best they could manage, and his guests’ clothing was finer than his own, at least in terms of appearances, but Jegari had said that he would go to his suite the instant they were in his father’s apartment, and bring him his best coat from his own bedroom closet . . . so he would go in to dinner with a proper respect and keep his mother happy.