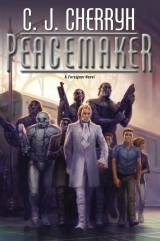

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

He trusted Algini and Jago not to let him be a total fool. And they stayed by him, tired, bloody, standing, then sitting on the edge of the lowest riser. Any coming or going around that open door through which Banichi had gone drew the same quick, tense glances, two atevi, one human.

It might be different reasons in the nervous systems. But what they fervently wanted right now was unquestionably the same thing.

13

No one had spilled anything—except Artur had bumped his water glass and nearly overset it. Artur had gone bright pink, and murmured, quite correctly, perfectly memorized, “One regrets, nand’ aijiin, nandi.”

“Indeed,” mani had said, and the grown-ups had nodded, and everything had settled again.

So had Cajeiri’s heart—as servants went on setting out the next course. It took Artur quite a while to change colors back to normal. Madam Saidin’s foresight had taught his guests that phrase—with the correct honorific for the circumstance, over which no few atevi might stumble in confusion. Irene had joked somewhat grimly that she had to memorize it perfectly, because she was sure to do something wrong. But it turned out Artur was the one; and Cajeiri caught his eye across the table and signaled approval, once and slightly, more a blink than a nod. Artur made an unhappy face back, just an acknowledgment—one had to know their secret signs to spot it.

There was a fruit ice, to finish. Everyone was happy with that. Throughout, they had hardly spoken a word, except Artur, and except Gene, once, to ask what a dish was: a servant had assured him it was safe, and the servant was right.

The grown-ups had talked about the weather—actually—talked about the weather. It had been that gruesome. Nobody was at ease. Nobody mentioned nand’ Bren, not once. Cenedi and Nawari should have been attending Great-grandmother, to hand her the cane when dinner was done, and to move her chair, and to do all those things. They were all stuck at the dinner table, in that huge room, with nothing to do, as if the air was afire and no one could mention it.

That was why, he thought, there had been no delay in serving dinner. That was why they had no more than gotten to the apartment before they were sent in to table, and why there had not been that long a delay, either, before his father and mother had come in.

The grown-ups knew what was going on; Cajeiri was sure of it. The rest of them knew something was going on. They all were wound tight as springs. Everything was. The servants were walking very quietly. Nobody but poor Artur had even clinked a glass, and that had sounded like a bell.

Now at last his father finished his glass of wine, and signaled the attending servant not to refill it. That was everyone’s signal that dinner was over.

“Shall we go for brandy?” his father asked.

There was quiet agreement, everyone rising, and Cajeiri got up. His guests did—servants moved to assist his guests in moving the chairs, though Gene managed—Cajeiri gave it only a little push to help it move straight back. So they all four gathered, with Antaro and Jegari, who had stood along the wall with the other senior bodyguards, and who now attended their lords: Lucasi and Veijico were out in the hall, where they ought to find out things—but he doubted they were learning any more out there.

What’s going on? Cajeiri wanted to ask Jase-aiji, when they came near, going out into the sitting room. He could ask it in ship-speak, and nobody but his guests would know what he asked.

But he feared to break the peace, such as it was, that kept questions out of the conversation and kept everybody polite. He went in with his guests, and as his mother and his father sat down—his mother, like them, to be served a light fruit juice and his father and everybody else receiving a brandy glass. His father asked politely whether his youngest guests had enjoyed their dinner.

There was crashing silence. It was an unscheduled question, one Madam Saidin had not prepared them to answer.

Then Irene said, in her soft voice, with only a little lisp, “Dinner was very good, nand’ aiji. One is very grateful.”

“Yes,” Gene and Artur said, both nodding deeply.

“Excellent,” his father said, and Cajeiri resumed breathing—there had been no mistake, no infelicity. He was not superstitious. Mani said superstitious folk were fools. But it felt as if any mistake they made could bring everything crashing down, everything balanced like a precarious stack of china. People he relied on were not here. They were about to go far off the polite phrases they had memorized for the occasion, and with nand’ Bren not here to fill up the gaps.

His father went on to ask Lord Tatiseigi about his art exhibit down in the public museum—and they talked about which pieces were there, and then wandered off into talking about Lord Geigi’s collection out in the west, and the effort to retrieve a piece that Lord Geigi’s nephew had sold.

Mani said that she was tracking it—and they went off about that, then stopped to explain the matter to Jase-aiji.

There was not a word about the Dojisigi or Lord Aseida.

There was not a word about what had gone on at Tirnamardi.

They just talked on and on. Jase-aiji had hardly said a word all evening, and he had had hardly a word from his parents, either—not “We were worried,” nor anything of the sort—which, considering they had come in from a situation with Assassins, and had sneaked into the Bujavid, seemed another considerable lack of questions. It was as if nothing had happened at all.

Then, after they had worn that matter out, his mother asked, almost the first word she had uttered, “Your guests, son of mine—they are all older than you, are they not?”

“Yes, honored Mother.”

He waited, wondering whether she was going to make some observation about that point, but she looked elsewhere, and meanwhile Great-grandmother had called one of her bodyguards forward and asked a question he could not hear. The young man seemed to say no, or something like no.

It was more than weird. It was getting scary.

He took a deep, deep breath then and asked, very calmly, very quietly, “Have we had any security alerts tonight, honored Father?”

“Nothing our guests should worry about,” his father said.

And almost as he said it, all the bodyguards twitched at once, and Jegari checked his locator bracelet.

Father’s chief bodyguard moved first, and went to his father, bent close to his ear and said something, no one else moving, everybody else watching.

His father asked a question, and got an answer that Cajeiri could almost hear, it was so quiet.

His father nodded then, and drew a deep breath. “Guild transmission has resumed,” he said. “Cenedi has just reported the mission is a success.”

“Excellent,” mani said, and Lord Tatiseigi and Jase-aiji all breathed at once.

“May one know?” Cajeiri asked, but mani was talking to his father and all he could do was try to overhear, because it was grown-up business, and he had the feeling it was very, very important.

There was something going on with the Assassins’ Guild. He caught that much. Some signal had hit everybody’s ear at once. His father asked whether documents had been filed, and his bodyguard said they had been.

It could be that his father had just Filed Intent on someone, but he heard no names, and his mother just looked upset. His father put his hand on hers and leaned over and talked just into her ear a moment. She nodded and seemed in better spirits then . . . so at least it was not something between them.

It was Assassins’ Guild business, he was absolutely sure of that. Some sort of papers were filed and something had upset his mother until his father reassured her.

He knew far more than his three young guests were supposed to know—that there was a little old man in offices in Guild Headquarters, who was behind a good deal of all their troubles, and that man’s name, Shishogi, was a name he was not supposed to mention. Shishogi was another of his relatives, and his mother’s relative, and Shishogi might have been involved in Grandfather being killed.

Had Cenedi possibly done something about Shishogi?

And where was nand’ Bren tonight? Maybe nand’ Bren’s bodyguard was helping Cenedi.

He wondered if his guests were understanding enough to make their own guesses.

And he would have to tell them, once he found out, but he did not expect that his father was going to say anything definite in front of them.

“Is there word from Bren-paidhi, nandiin?” Jase-aiji asked then.

“Well. He is well,” was the answer.

Well was very good news.

But why did his father have to assure Jase-aiji that nand’ Bren was well? Had nand’ Bren anything to do with Shishogi, if that had been what was going on?

Maybe it had been some other problem.

At least the grown-ups were relaxing. Father called for another round of brandy and fruit juice, and the bodyguards, from stiffly watchful, had moved together, opened the door to the hall, and were conferring in their own way, passing information which Cajeiri desperately wished he could hear.

“What’s going on?” came a whisper from Gene.

“The Guild,” he whispered back, in Ragi, and then in ship-speak, quietly, so his mother would not hear: “Our big problem, maybe. Fixed, maybe. Not sure.”

Gene passed that on to Irene and Artur, heads together, and his mother was, at the moment, talking to his father, so they went unnoticed.

Whatever had happened, the Guild meeting at the door broke up, and bodyguards went back on duty, with no different expressions. That was all they could know, because nobody was going to say anything to his guests. Antaro and Jegari had moved over to the door and had not moved back to the far side of the room.

But he had no wish to have his father officially notice that his very junior bodyguard knew anything about his father’s business. He so wanted to call them over as everybody else had and ask what was going on, but he decided not to attract grown-up attention. He would find out when the dinner was officially over and they all could go back—

He hoped they could all go back to Uncle Tatiseigi’s. He hoped not to be moved back here to his father’s apartment, if there happened to be any thought of that, now that whatever emergency had been in question seemed settled. He had no inclination to attract any sort of reconsideration from the grown-ups.

Clearly mani and Great-uncle were not going to leave yet. They were all going to sit here and drink brandy and fruit juice, probably until there was some sort of all-clear. He had experienced security alerts often enough in his life that he knew how that went.

So he had another glass of fruit juice himself, and distracted his guests with a little running side conversation about how the conspirators during the coup had shot up his father’s apartment and how, when they had come back to Shejidan, they had had to live with mani until workmen could completely redo the apartment—cutting off any access to the servants’ passages on the floor below, and moving walls around, swallowing up one apartment that had been across the hall and shortening the hallway outside . . .

It was a stupid topic, but it was the only distraction he could think of with examples he had at hand. His guests were polite, and listened politely, while their attention kept flicking off toward the adults, who were having their own discussion, once bringing mani’s and father’s bodyguards back in for another conference.

The old man in the little office.

That was in Guild Headquarters.

· · ·

They sat in the well of the Council Chamber while the whole building echoed with movement, and now and again to heavy thumps, possibly the clearing of barricades, or dealing with one of the ruined doors.

Bren and Jago and Algini sat, shared a cold drink of water that one of Cenedi’s men had provided—and waited. Nand’ Siegi had long since arrived with his own medical team. They had that comforting word. And very likely there would be triage. Banichi would get care—but there would be some sort of priorities established. And questions would only add to the problems.

At very long last Tano came in from the lower corridor, and immediately nodded reassurance as he shut that door. Tano joined them—cleaner than they were, wearing just his uniform tee, and with face and hands well-scrubbed. “He’s done well,” Tano said. “The bleeding is stopped. Nand’ Siegi found the source, which was exactly what Banichi himself said. He is out of danger, nand’ Siegi assures us, granted he stays quiet. His color is improving. It is up to us to assure he follows nand’ Siegi’s orders, takes his medicine—and he is to have no more of the stimulant he was taking.”

The knot in Bren’s stomach had begun to unwind itself. When Jago asked, “Impairment?” and Tano answered, “If he follows orders, no impairment that exercise cannot mend,” then all the tension went, so that he leaned against the railing behind him.

That was a mistake. His head hit the rail above and sent a flash of light and pain through his skull. But it didn’t matter. “He will follow orders,” he said calmly. “He will. God. What a night.”

All around him were locator bracelets functioning normally. The halls reverberated with confident strides . . .

And the aiji’s personal train was sitting out there mid-tracks, blocking the normal mail train and all the freight deliveries that should be going uptown.

He had washed his own hands and face in a small lavatory adjacent. But his coat and his trousers were caked with blood that was drying at the edges, making it necessary to watch where he sat. His head throbbed. He didn’t care. Now it was all right. Everything was entirely all right. He found his hands shaking.

“Sit down, Tano-ji. Rest for a bit.”

“I have been sitting, nandi. I have to go back down to restrain my unreasonable unit-senior when he wakes up.”

“We probably should move that train,” Bren said. “If it would be all right to move him onto it.”

“I believe it should be,” Tano said. “We can likely move him aboard, as he is, with very little problem.”

“We should not have the paidhi-aiji outside the building without sufficient guard,” Algini said. “Jago-ji, go up and advise Cenedi we shall need escort, at this point, to return us to the Bujavid.”

“Yes,” she said.

“Pending approval from nand’ Siegi,” Bren said. “We will do nothing against Banichi’s health.”

“Yes,” Tano said, and left again.

· · ·

Father set down his brandy glass, which was the signal for everyone to take notice. “We have had a very good evening,” Father said, “and the aiji-consort needs her rest. Certainly our son and his guests need theirs.” A nod, to which Cajeiri nodded politely, sitting on the edge of his seat—and hoping for a word with Jase-aiji once they got to the hall.

“We have had a very great success,” Father said, “an excellent dinner, excellent guests—” More nods. “Nod,” Cajeiri said, and his guests took the cue and bowed.

“So,” his father said, “let us bid our guests good night and good rest, and to our son, a special good night. We are very glad you are back safely in the Bujavid, and we welcome your guests.”

“Honored Father.” A second, half-bow, as best one could, while seated.

His parents got up. Everyone did. His father’s bodyguards opened the doors, and the senior guests went out into the foyer. So did his mother and father, which they ordinarily would not do, but his father was in an extraordinarily good mood, one could tell it, and exchanged a word of thanks to Jase-aiji, who had had one of his two bodyguards evidently standing in the foyer all evening. Cajeiri gave a little signal to his guests and led them out quietly, so they all stood in a row, waiting to go out with everybody else.

“Nand’ aijiin, nandi,” Irene said, then, in a breath of a space, and he suddenly knew Irene was going to say something—Cajeiri held his breath as all the grown-ups looked at his guests as if the hall table had just spoken. “We wish to thank the aiji and his household for his hospitality. We are greatly honored.”

There was a little astonished silence. Then his father nodded politely, and his mother—Cajeiri took in a breath—asked: “What is your name, child?”

“Irene, nandi. My name is Irene.”

“Come.” His mother beckoned Irene closer, and closer, and closer. “You are also older than my son, are you not, nadi?”

“Yes, nandi.” Again, and properly, a little bow. His mother reached out toward Irene—not to touch, but her hand lingered close.

“Oldest of all your associates, in fact.”

“Yes, nandi.”

“So small. You are so very small.” His mother drew her hand and rested it above the baby, and it was a curiously gentle move, as if his mother were on the verge of deep distress. “I shall have a daughter soon. I look forward to it. Have you enjoyed your stay, Irene-nadi?”

“Have you enjoyed your visit?” Cajeiri rephrased it, feeling as if the whole business could explode at any minute. But his mother seemed quite gentle in her manner, very restrained, looking for something.

“Yes, nandi. Very much, thank you.”

“A mannerly child. And your associates? Gene? And Artur?”

“Yes,” Gene said, and bowed. “Yes, nandi.”

“Artur, nandi,” Artur said, doing the same.

“So.” His mother nodded, and looked at him, and looked at Irene. “Your family approves your being here?”

“The aiji-consort asks,” Jase-aiji translated to ship-speak, while Cajeiri was trying to think of the words. “—Does your mother approve your being here?”

Irene looked at him, and hesitated, and it was not a simple answer. Nothing about Irene’s mother was a simple answer.

“Yes, nandi,” Irene said cheerfully, with no hint of a shadow in the answer.

“Good,” his mother said. “Good that your mother was consulted.”

“Honored wife,” Tabini said, “we should let our guests go to their beds, should we not?”

“Indeed.” She turned a slow glance toward mani, toward Great-uncle, and lastly toward Cajeiri. “Well done,” she said to him, “well done, son of mine.”

Well done? He could not recall ever hearing that from her. Scarcely even from his father.

“Good night, honored Grandmother, nandi,” his father said. Great-uncle and mani took their leave, sweeping Cajeiri and his guests toward the hall. Cajeiri looked back, from the hall, and nand’ Jase was still talking to his father. Jase’s single bodyguard walked out into the hall and stopped again, like a statue. Two of his father’s guard came and stood there, too.

When he looked all the way down the hall, he saw another white statue down at the far end, by Great-uncle’s apartment, with two black-uniformed Guild standing beside him. So that was where Jase-aiji’s other bodyguard had been all evening.

That was scary.

Jase-aiji came out behind them; and the one bodyguard went with them and the other began walking toward them from the far end of the hall. Jase-aiji walked as far as nand’ Bren’s apartment and stopped and wished them all good night. That door opened and Jase-aiji went in, but the bodyguard who had been with them just froze where he was, still standing guard in the hall. The other one had stopped by Great-uncle’s door, likewise frozen.

And Great-uncle and mani just kept walking toward mani’s apartment.

Were they all just supposed to go home now and go to bed, as if nothing unusual was going on?

Mani and her bodyguard stopped at her apartment—with never a word, except, from one of mani’s bodyguards, “Cenedi reports everything quiet, aiji-ma. Nand’ Bren is returning.”

From where? Cajeiri desperately wanted to know.

But mani went in, and he and his guests and Great-uncle and their bodyguard just walked on.

“Great-uncle.” Cajeiri had no hope of an answer, but he tried. “May one ask?”

“Everything is very well,” Great-uncle said, and added: “The Assassins’ Guild has just changed leadership, young lord. The guards are precautionary, since there may still be individuals at liberty in the city. But one rather supposes the Guild will sort out its own very quickly. This is a former administration of the Guild, and they will set things to rights as we have not seen in at least three years.”

He was in awe. Great-uncle had never been so forthcoming, as if he were someone, instead of a child. “Great-uncle,” he said very respectfully. “One hears. One is grateful to know.”

“Do your guests understand?” Great-uncle asked. “One rather thinks they know something has been amiss.”

“I shall tell them,” he said. “They are worried. But I shall explain, Great-uncle, so they will understand.”

“Indeed,” Great-uncle said, and they arrived at their own door, which Madam Saidin opened for them.

Will Kaplan and Polano stand there all night? he wondered. Perhaps they would.

But things were going to be set to rights, Great-uncle had said.

And the Guild that protected everything had changed leadership—

And what about the old man who had caused everybody so much trouble?

Was their enemy in the Guild now gone?

He wanted to know. It seemed major things had gone on and nand’ Bren was somewhere in it, and so, he guessed, was Cenedi. The whole world had been in some kind of quiet commotion tonight—and how much he and his guests had been at risk in it, he was not sure, except that they were still being taken care of and kept safe and he had most of all to keep from scaring his guests—and most of all, their parents.

Maybe the world was really going to change. Things set right, Great-uncle said, and he could not quite imagine that. People could always turn up hunting them—and clearly nobody was taking chances in this hall, tonight.

But nand’ Bren was coming back, and Cenedi was reporting in, so he decided, as Great-uncle’s doors closed behind them—that he really could tell his guests everything was all right.

· · ·

The Red Train was back in its berth, no longer blocking rail traffic. Mail was moving again. Freight deliveries were happening. Day-shift employees were finally able to take trains home, those who had not given up and walked. Night-shift employees could get to work in the city.

But the councils of other guilds in all those other buildings—Transportation, the Merchants, the Scholars, were reportedly in emergency session, trying to inform themselves what had just gone on in the Assassins’ Guild.

Nobody of a certain rank was getting much sleep tonight.

Neither, Bren reflected, was the paidhi-aiji or anybody around him. They reached the apartment, bringing Banichi with them, medical gear and all, bound for the comfort and safety of the security station in the depths of the apartment.

Jase’s men were still on watch out in the hall, with Guild beside them to watch with ordinary atevi senses—and with the ability to recognize anybody who had reasonable business on the floor. Jase had made it back to the apartment before him, exchanged court clothes for a night robe—and met them coming in.

“Good God,” was Jase’s comment, seeing their bedraggled condition, and Banichi, on the gurney they had borrowed, with the ongoing transfusion: “How bad?”

“It could have been far worse,” Bren said. “Nand’ Siegi’s patched him up again—he’s to stay quiet.” His voice was breaking up . . . too much smoke, likely. “How did it go with the dinner?”

“Very well, actually. Better than you had . . . clearly. Can I do anything?”

“We’re just good for rest, letting Banichi just rest and stay quiet. Maybe a cold drink. A sandwich.” He said the latter as Narani stood by, awaiting instructions, and the delivery of his ruined coat. He shed it—shed the stained vest and even the shirt. It was an impropriety in the foyer, but they were not standing on ceremony, and their garments were shedding a powder of dried blood, too filthy even to let into the bedroom. “Forgive me,” he said, “Rani-ji, I think everything I have on is beyond rescue. I shall shed the rest in the hall. I shall try not to touch the furniture. One believes the crates with our wardrobe will arrive tonight, or tomorrow.”

“I shall draw a bath, nandi.”

“Draw it for my aishid. For me, the shower will do very well.” Jago had done a field repair on the rip in his scalp—loosed a few hairs about the cut and knotted them together, closing the wound, and Tano had poured astringent on it. That had hurt so badly he had all but passed out—quietly, however, with dignity. He had managed that, at least, a nice, graceful slump that had not ended on the Council Chamber floor only because Algini had held him up. His aishid had wanted nand’ Siegi to have a look at the patch job before they left—but he was sure it was, despite their worries, enough for tonight. He had his own little pharmacopeia in a dresser drawer, including an antibiotic he could take. He dreaded the thought even of trying to shower the blood off his hair, but he had to: it was a mess. And he was sure Jago’s repair would hold.

“My aishid,” he said to Narani. “They should have—whatever they want. Anything they want, nadi-ji.” He changed languages, for Jase. “We did what we went in to do. The old man’s dead . . . he tried to take out the records, but we’ve got most of them. The returnees have control of the Guild. They’re going to be sorting the rank and file for problems, and we’ve probably got a few running for the hills by any means they can find. But the new ones, the ones that’ve come into the Guild during the last three years, are reporting in from all over the aishidi’tat, asking for instructions, realizing there’s been a change of policy. There’s a good feeling in the wind. The younger ones have got to be confused, but apparently the reputations of those taking charge carry respect. The Missing and the Dead, as Jago calls them, have just risen up and taken over.” His voice cracked. “And we’re going to see a Guild we haven’t seen since we left the planet. Which is good. Very good. They’ll argue with Tabini. But at least they won’t undermine him. And there won’t be anybody conducting intermittent sabotage from Assignments.”

“Go get that shower,” Jase urged him. “Go sit down. If there’s anything I can do—let me know.”

“Thanks,” Bren said, and headed down the corridor toward his bedroom, and the chance to shed the rest of his clothes in some decency.

But sleep? He didn’t think so.

· · ·

“Has he waked?” he asked Tano, who had, with Jago, sat by Banichi the while.

Banichi’s eyes opened a slit, a glimmer of gold.

“He is awake,” Banichi answered for himself.

“Good,” Bren said, and sat down on the chair Tano snagged into convenient proximity for him. “How are you doing, Nichi-ji?”

“One sincerely regrets the distraction in the Council chamber,” Banichi murmured faintly. “And the general inconvenience to the operation.”

“We did it, understand. We took down the target.”

“So one hears,” Banichi said. “Cenedi has come back?”

“Cenedi is on his way back to the Bujavid,” Tano said. “The Council is in session, probably at this moment. Other guilds are meeting to hear the reports. They are not waiting for morning.”

“The city is quiet, however.”

“The city is entirely quiet,” Jago said from her spot in the corner. “The city trains are running again. The city will only notice the mail is a little late tomorrow.”

“One believes,” Banichi said, “the rumors will be out and about.”

“One believes they will outrun the mail delivery,” Tano said. “The aiji will make an official statement to the news services at dawn. The legislators are being advised, some sooner than others.”

Those who employed bodyguards, notably lords and administrators all over the continent, would have been waked out of sleep by their bodyguards, giving them critical news from the capital. Viewed from the outside, the Bujavid’s high windows probably showed an uncommon number of lights in the small hours tonight—the sort of thing that, in itself, would have the tea shops abuzz in the morning, if they had not had the stalled train for a topic. And a number of people would be both up late and rising early—not quite panicked, but definitely seeking information . . . which that Guild of all Guilds might not release, except to say that the leadership of the Guild was now the former leadership, with the former policies. One could almost predict the wording.

The damage within the Assassins’ Guild had been very limited—only three deaths in the whole operation, the target being one, and the other two, Algini said, died firing at a senior Guild officer who had identified himself.

Finesse. Banichi’s plan had gained entry into the heart of the building for the returning Guild. Cenedi’s had been the action in the administrative wing while the initial distraction was going on. And both had come off as well as they could have hoped.

“Juniors who have come up during the last three years,” Algini remarked, “will be finding out that the rules on the books and the rules in operation are now one and the same.”

“That may come as a great shock to some,” Banichi murmured, and moved one foot to the edge of the bed.

“No,” Bren said. “No, put that foot back, nadi. You are not to move, you are not to sit up, you are not to shift that arm, and you are not to take any more of those pills you have been taking.”

“The arm is taped,” Banichi said, “and I am well enough.”

Bren held up his fist—with the aiji’s ring glinting gold in the light. “This says you take nand’ Siegi’s orders. Do you hear?”

“One hears,” Banichi said. “However—”

“No,” Bren said. “You have your com unit. You have your locator. You may move your other arm, but you are not to lift your head, let alone sit up. When nand’ Siegi says so, then you may get up.”

Banichi frowned at him.

“I am quite serious,” Bren said, rising. “It is the middle of the night, the household is hoping for sleep, and there is no good worrying over details out of our reach. If the leadership you left in the Guild cannot lead after all this, we are all in dire difficulty, but one does not believe that will be a problem. We are certain they have some notion what to do next. So sleep. Well done, Nichi-ji. Very well done.”

“Nandi,” Banichi said faintly.

“So stay in bed,” Jago said, and reached for a glass of what was probably ice water. “Have a sip.”

“One cannot drink lying flat,” Banichi objected.

Bren left the argument, however it might come out, and made his way down the hall barefoot. His head hurt—it didn’t precisely ache; or maybe it did. His scalp certainly hurt. The repair held, however. And he was exhausted. Sleep—he was still not sure was possible. He didn’t think he’d sleep for the next week, his nerves were wound so tight.