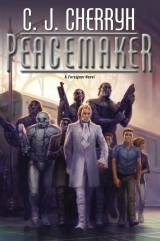

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Tabini-aiji hadn’t had to organize the city event: city officials, guilds, vendors and licensed purveyors of this and that knew exactly what to do, since they did it several times a year. The aiji only needed issue one phrase in his decree: a day of public Festivity . . . and the restaurants would be preparing to fire up their mobile carts, the vendors would pick their wares, the district officials would prepare banners to be hung, and the whole nation would start looking for train and plane tickets before the echoes died . . .

That would have begun on the very morning they’d been out riding at Tirnamardi, enjoying life.

Well, it was positive politics, this time, a happy event, a chance for people to enjoy themselves.

The numbers had turned out, and the aiji was ready to state that there would be no consideration of a second child as heir. Whatever numbers had prevailed in Cajeiri’s life were taken into account, accepted as favorable, apparently with no more argument.

With human guests to witness it.

With the whole nation to witness it.

Tabini had made his move, one could guess, in some apprehension his own existence was at risk.

Tabini had had no advisement the aiji-dowager was going to make hers in her own fashion, double or nothing, and take on the Guild. They’d surprised each other.

He was not too surprised when a message arrived from the dowager’s apartment, under the dowager’s personal seal.

It said: We trust you have heard from our grandson. Of course the numbers are felicitous. We have seen to that.

Jase-aiji and the young guests will not forget this event. And their attendance will stamp them forever, if they are wise.

Jase-aiji often speaks to the ship and to Lord Geigi. They should not, in decency, be informed yet. Advise him.

The aiji-consort may have her child. We can now be sure of ours.

We are very pleased.

Damn, he thought. But there was nothing in the letter or the conclusion his aishid did not know. It only remained to slip the hint to Jase—without himself being certain quite what the dowager meant by stamp them forever.

“I have a notion,” he said in that conversation with Jase alone in the sitting room, “that the ship-captains and the human authorities are getting a strong signal from Tabini-aiji and the dowager. One only wishes one understood it.” He spoke in Ragi, naturally as breathing, and switched languages, to enter another referent. “A signal about the status of those kids.”

“Does she know about the pressure—to send the Reunioners off to Maudit?”

“She may,” he said. “Between you and me, it’s at least a signal her personal plans don’t include Maudit.”

“I’m not sure I get the nuance. Am I included in this idea?”

“Three kids. One of you. It’s an infelicity if combined. The verb governs all preceding.”

“So I’m included.”

“I think definitely. She’s handed you responsibility for those kids. And they’re not going to Maudit.”

Jase had a troubled look in his eyes. “I had both figured on different grounds, actually, before the message. Tell her, since I figure you’re the designated channel, and I shouldn’t write to her unless she writes to me—”

“That would be true.”

“Tell her I’ll protect the kids. Personally. And officially. And no, if she asks, I’ll keep this from the ship until she agrees I can say something. I answer to Sabin on this, but her word to me was—you make the judgment call.”

Sabin, senior captain, was no fool. Let the one of the four fluent in the language and adept in the culture assess what was going on on the planet. And with the four captains in agreement, and with Lord Geigi, head of the atevi space authority, backing them—the Mospheiran station authorities would be fools to back the emigration of the Reunioner refugees, badly as the Mospheirans wanted to shed the Reunioners . . . who were, never to forget it, actually under the four captains, not the Mospheiran government.

Politics, politics. The aiji-dowager had just, in the atevi proverb, taken hold of the strongest stick to stir the stew, not attempting to use her fingers.

“So the kids aren’t going to Maudit,” Bren said.

“No,” Jase said, a breath of an answer. “Given how things have turned out down here, not any time this century, if I have anything to say about it.”

17

It was the day. It was finally the day. Cajeiri was out of bed at the very first urging, dressed in the better-than-usual shirt and trousers his valets presented, and was slipping on a day-coat when Gene and Artur came rolling out to say, somewhat confusingly, “Please enjoy the day you are born!” And then in ship-speak: “Happy birthday, Jeri-ji!”

He grinned. It was impolite, but he was so happy he could hardly help it. He bowed and said, “Thank you, nadiin-ji,” just as the other lump in the bed sat up and became Irene, with her pale hair every which way. “Oh!” she said, and grabbed her nightrobe in embarrassment, with Eisi and Liedi standing there, and herself where it was not quite proper for her to be.

“We layered the bedclothes, nadiin-ji,” Cajeiri said with a calm little bow, “and we are all very proper, all of us.”

“Indeed, nandi,” Eisi said, unperturbed, and about that time Veijico and Antaro turned up out of their room, in proper dress uniform.

“Happy birthday,” Irene said, from her seat deep in bedclothes. “Happy birthday, Jeri-ji!”

“A felicitous ninth!” Antaro called out. “Our young gentleman has reached his fortunate year!”

The other door opened. Lucasi and Jegari were there, half in uniform. “Felicitations, Jeri-ji!”

“Felicitations, nandi,” Eisi said with a solemn bow, and “Felicitations!” Liedi said.

Boji just shrieked and rattled his cage in excitement.

“Your honored uncle bids you and your guests to breakfast,” Eisi said. “As you please, nandi.”

It was the best morning ever. It truly was.

It was the best breakfast ever, because Uncle’s cook had been asking him ever since they arrived what his favorite things were for every meal, and it was everything he liked in one huge breakfast, just himself and his guests, because staff said Great-uncle was having breakfast with Great-grandmother, and they would all meet for a state lunch at his father’s apartment. Nand’ Jase was to come for him half an hour before noon, but the state lunch was for mid-afternoon because there would be no supper, only the Festivity buffet in the Audience Hall.

That was the gruesome part. He could not have his aishid with him at the moment—Jegari had told him before he and the others had left—because they had to go ahead to nand’ Bren’s apartment and talk to Tano and Algini about codes, which was why they were missing breakfast, and they would meet him there when Jase-aiji brought them all there.

That was one thing he wished somebody had asked him. He would have had cook send a special breakfast for everybody.

Then Madam Saidin stopped him as he left the breakfast room and handed him a rolled paper.

“This is from your father the aiji, young gentleman, your speech to memorize for the Festivity tonight.”

“A long one?” he asked anxiously.

“Only a few lines,” she assured him. “Very short.”

Well, that was not too bad. And Madam would not lie to him. So they all trooped back to the guest quarters, his guests all in good humor, to sit and let breakfast settle for two hours. He got to change to court dress, at least all of the suit except the coat, and his guests got to sit about in comfortable clothes. He was envious of that.

He had to suffer a scratchy flood of lace and memorize a stupid speech.

He unrolled the paper to find out what he had to deal with. And it was not three lines, it was three whole paragraphs.

It started:

I thank all my family, all my associates, all my allies, all my family’s allies, all you good people. I am fortunate nine, today, and I thank you for coming. I thank my mother, who has done her best to guide me, and my great-grandmother . . .

And it went on to say things like:

...lords of the associations, lords of the districts, lords of the provinces, thank you.

...urging cooperation toward a prosperous and felicitous year . . .

He dropped into a chair and went on staring at it. It was a horrid lot of categories to remember in order, and his mind was every which way today.

But he could do it. He had memorized all the districts and the capitals and the imports and exports and the lords and their heirs and their families. He had memorized the names of the treaties, in order, that had built the aishidi’tat. He saw them, and he kept thinking of heraldry and emblems and imports and treaties, when he needed to be thinking about the words.

He had memorized the descent of his family from the War of the Landing.

He had memorized . . .

With a prodigious shriek, Boji streaked to the chair, seized the paper and, trailing his chain, carried it off to the top of the bureau.

“One is extremely sorry, nandi!” Liedi exclaimed.

“Let us not startle him,” he said calmly. “Close all the doors.”

They would not make that mistake.

But all of them stalking Boji made Boji nervous, and with the paper in his teeth, Boji leapt for a tapestry railing, then for the crystal chandelier, setting it rocking and jingling, but trailing the chain.

Eisi snagged it, and tugged. Boji jumped for Eisi’s shoulder, sending the chandelier swinging wildly. Snagged, Boji threw a screaming tantrum and bared his teeth, crumpling the paper in his bony little fist when Eisi tried to get it away from him.

“Boji!” Cajeiri said sharply, and Boji looked his way, wide-eyed above the mangled paper in his paws. “Come here! Come!”

Boji fixed on him. That was a good sign. He held out his hand, and Boji nipped the paper in his teeth and took a flying leap for his arm, where he wrapped himself with all four limbs, Eisi still holding the chain.

“Give it to me, Boji,” Cajeiri said. “Give it to me.” To his surprise, a little tug freed the mangled paper from Boji’s hands. He took the chain from Eisi and, since he was still in vest and shirt, he let Boji run up to his shoulder and perch there, even if his feet hurt. He had the chain. He had the paper. His guests were all amazed and amused and impressed.

He gave the paper a little snap and casually handed Boji off to Liedi, feeling very grown-up, very dignified. Even Great-grandmother could not have called Boji to good behavior. But he had.

“That’s pretty good!” Gene said.

“He’s adding it up,” Irene said. “He knows who to salute, doesn’t he?”

“Smart,” Artur agreed.

He tried not to seem surprised at all. He uncrumpled Father’s letter, which had gotten chewed a bit, and had holes here and there, but it was good enough. He glanced at it enough to know all the words were there.

“Are parid’ji relatives to atevi?” Artur asked, which was a question that upset some people, mani said, but Cenedi had said probably, and his tutor had said . . .

“Maybe,” he said. “There were bigger. There still could be in the mountains on the Southern Island, maybe even this far north. The parid’ji used to live as far south as Shejidan, but all that forest went away. There used to be forest all the way across the Atageini ridge and clear on to the mountains, a long, long time ago. And there was forest all over the Southern Island, except the coast. But that was before the three islands blew up.”

“Volcanoes?” Artur asked in ship-speak. “Mountains and fire?”

“Big explosion!” he said. “Volcanoes.” He wanted to remember that word. “The big map in my office.” That sounded so important. “I can show you where.”

Their eyes lit up. They were excited.

So had he been excited when his new tutor had told him one of the isles was reportedly reappearing above the waves and smoking—and he had immediately had a wicked thought that nand’ Bren’s boat might be able to go to the Southern Island and even down to the Southern Ocean . . .

But then his tutor had talked about the weather in the Southern Ocean, which was why ships did not sail any further south than from the Marid up the west coast, and why the seas between Mospheira and the mainland were far calmer than the open seas where the winds blew all the way around the world without any land to stop them. When the three islands had blown up, that had been the barrier to the Southern Island’s east coast, so even going there now was dangerous.

Lord Machigi’s ships, big metal ships, were going to sail all the way around the teeth of the southern shore, and clear up to mani’s territory in the East. That was part of the new agreement between mani and Lord Machigi. And nand’ Bren said they thought they could do it, if the space folk helped them. He should ask nand’ Jase how they could do that . . .

But the question at hand was about parid’ji and their ancestors, and how the forests had used to be. So with a grand flourish of his cuff lace, he took a stylus and pointed out the continental divide on his beautiful wall map, and told his guests about the white-faced parid’ji which people had used to think were dead people come back to visit them . . .

“Ghosts!” Irene reminded him of the word.

“Ghosts!” he said. And he knew a lot about the superstitions of the East, which he had told them on the ship, in the tunnels, where he had told them about the visiting dead near Malguri and all sorts of scary things they had liked.

They were excited, and with the map he could show them all sorts of things, and every location of every ghost story he knew about . . .

Right until Madam knocked at the outer door and brought Uncle’s staff to gather up his guests’ wardrobe on racks to take to nand’ Bren’s apartment. He had lost track of the time he had. It was almost time for nand’ Jase to come get them.

Well, that was all right. He memorized fast. He pulled the mangled paper from his coat pocket and he would be very careful, when staff wanted him to change to his Festival best, to be sure that paper went with him. He was sure he would get plenty of time to memorize the speech once he reached his father’s apartment. He always had to do a lot of waiting about: everybody said they needed him, but it usually amounted to him sitting in a corner bored and waiting while his father attended some business that had come up.

The rack of court clothes rolled out a back servant’s passage, disappearing into the hidden corridors to reappear, one was certain, in the back halls of nand’ Bren’s apartment, part of the mysteries of servants.

And it had no sooner rattled off out of the bedroom than Madam reported Jase-aiji had arrived to escort them.

“Here we go,” Gene said, as if they were about to take off and fly.

“Here we go,” he echoed. He had yet to be presented his court dress coat. He had on only its vest, a very elegant black and gold. He carried the paper in his hand, and let Madam show them out into the corridor and as far as the front door.

Nand’ Jase waited outside, with his bodyguard in their scary, noisy white armor—but with the faceplates up, so it was just Kaplan and Polano, familiar and lively, in all that strange skin. Mani’s guard, Casimi, had come along, too, perhaps for the numbers. Eisi and Liedi were going to go along to nand’ Bren’s to help his guests dress—but also because nand’ Jase was not as good with Ragi as nand’ Bren, and Kaplan and Polano could hardly put words together.

His valets helped him put on the beautiful court coat Uncle’s tailor had made him—he liked the lapels and wide cuffs, especially, which were inky black, and the rest was all gold and black brocade, the black shiny and the gold sparkly. He slipped the paper into the broad right pocket, patted it flat as he went out, and gave a little bow to Madam Saidin, concerned that his parents might not let him come back this evening, or maybe not even tomorrow, once his parents got their hands on him.

“Thank you, Saidin-daja,” he said. “One hopes one is coming back. Thank cook and thank my great-uncle.”

Great-uncle had not shown up to see them off. But he would see Uncle at lunch, he was quite certain.

And maybe if mani could not get him free of his parents’ apartment, nand’ Bren could invite him, and make everything work out.

· · ·

The youngsters’ wardrobe preceded them, a rattling arrival in the middle hall—there was no missing it. Bren straightened his cuffs, done up in his own court dress, there being no sense dressing twice in the day for an appointment at lunch.

Not so with the youngsters, who arrived in the foyer all shyness and anxiety, with nervous little bows.

“You’re doing fine,” he said in ship-speak, at which there were deep breaths of relief. “Do you understand the schedule? Captain Graham will be back in a moment. He’ll be with you through all the events and you’ll need to stay close to him at all times. Make yourselves comfortable in the sitting room. Is there any problem?”

“No, sir,” Irene said. “We’re all right.”

“Don’t be nervous. Come.” He showed them into the sitting room, where young staff had laid out tea and very small sandwiches. “There will likely be a very fancy lunch, but you daren’t spill anything, and not everything will be safe to eat. My advice is eat all the sandwiches you want before you go, so you’re not that hungry, and when it comes to the buffet tonight—this is very important—stay to the desserts.”

“Neat!”

He had to grin. “I know. Not a hard idea. The desserts are safe—if I spot one that isn’t, I’ll advise Jase. The rolls are safe. Staff is supposed to be careful of you. But if you want to try anything, ask Captain Graham and don’t experiment, not even a taste, no matter how good it looks: we don’t want you to spend tonight in hospital. There’s one tea you absolutely shouldn’t have. He’ll warn you. Fill up here where you know the food is safe, eat very carefully at table and don’t risk spilling anything on your clothes. It’s going to be a long, long day. You’ve been excellent guests. Keep it going just another few hours. It’s very, very important to Cajeiri that you not make a mistake.”

“Yes, sir.” Heads bobbed. Looks were very earnest.

“Anything we can do, anything you need, or if you’re in distress, Jase first, then me, or any of my staff. Got it?”

“Yessir.”

Excellent kids, he thought. Kids who’d been warned within an inch of their lives—but kids who’d borne up in good humor through a hell of a lot that hadn’t been in anyone’s planning.

“You’ve been good beyond any expectation. Carry this evening off for him and there’s an outside chance we can send you somewhere you can have some fun, maybe with the Taibeni.”

“The mecheita-riders?” Eyes went large.

“They’re completely loyal to Cajeiri. A very safe place. And I’ll do everything I can to arrange it, if you just do everything you’re asked, be patient with delays, and don’t mess it up. Twelve more hours, and if the aiji’s enemies don’t create a problem, you’re out of it and clear. Jase will be here in a moment, and he’ll fill in the rest for you.”

God, he hoped he was telling the kids the truth. The combined force of staring, believing eyes went right to the nerves, while his if was still a very big word.

· · ·

“Nandi,” the major domo said, welcoming Cajeiri and his bodyguard into the foyer. Jase-aiji paid courteous nods and immediately left, going back up the hall. “Welcome home, young gentleman.”

“Nadi,” Cajeiri said with the requisite little bow. Servants were close about them—until the ones near the inner hall folded backward in startlement, ducking heads, as his father arrived, his father likewise in court dress, and solemn, and accompanied by two of his bodyguard. All the servants backed up, clearing room, and Cajeiri gave a deeper bow.

“Son of mine,” his father said solemnly. “You look very fine.”

“One is gratified, honored Father.”

“And everything is going smoothly?” his father asked, coming very close to him.

“Yes, honored Father.”

His father took him by the arm very lightly and maneuvered him so that he could speak close to his ear. “Son of mine, you look particularly elegant, and so does your aishid—a credit to your great-uncle’s household, but one needs to forewarn you. Your mother is already having a difficult day, and so is the staff. Your mother had secretly ordered a coat and vest from your regular tailor, and she was not willing to deliver it to your great-uncle’s house, but your tailor is greatly out of sorts about this, and this being her present to you—it has set her out of sorts. If you wish to please your mother—and one advises you this would be very desirable today—send staff to your suite and have them bring the black and red brocade instead.”

He liked his black and gold brocade coat, which his mother would call too old for him, but he was nine today, and he had three red and black ones, besides. He said quietly: “Uncle had Master Kusha come in because of my guests, honored Father. They had nothing suitable, and Master Kusha and his staff worked very hard.”

“One will do everything to honor master Kusha’s efforts, but you would not be politic to ignore your mother’s gift, son of mine. And besides, the ’counters have figured red into the numbers.”

He was not happy. But he understood. “Yes,” he said, and to Jegari: “You know my coats. Can you recognize the new one?”

“Assuredly, nandi,” Jegari said, and with a bow to his father, hurried off through the servants and down the inner hall toward their suite. Cajeiri began sadly unbuttoning the elegant black and gold coat, and his father helped him, with that and with the vest, right there in the foyer in front of everybody. He was sure he blushed, and he was angry about it, but his father was on his side, which was the important thing. And he knew how much politics with his mother mattered, for everybody’s good.

Next time the ’counters did the numbers, however, he swore he was going to have his say in it. And wear black and gold if he wanted to.

But it would be his thirteenth birthday before he ever got another festivity, and his fifteenth before another big one, which he swore was not going to be public, either. He was verging on a bad mood. And could not afford to sulk.

“Very well done,” his father said, handing off his favorite new coat and vest to the major domo, who gave it to the servants to deal with. “Be agreeable, do not frown at your mother, and thank her nicely for the new coat and vest, if you can possibly manage it. Count it training.”

“Yes,” he said. By then Jegari was back, with the new coat and vest, which at least went well with the black trousers and boots, the new vest being shiny black with glittering red woven in, and the coat being nearly all black with a little red—the vest at least fit well, as it should, and the coat fit, and his father with his own hands helped him do all the buttons, in front of all the servants and their bodyguards.

“One is very impressed,” his father said. “You have grown in more than height this year, son of mine. One is very proud.”

That was twice for blushing, but this was for a different reason. He gave a little bow as his father finished the last adjustment of his lace cuffs. “Thank you, honored Father. One will try very hard today.”

“Come to the sitting room,” his father said, and showed him the way as if he were an adult guest in his own home.

His mother was there, in black and green, Ragi and Atageini colors combined. She looked pleased as he came in, and mani had taught him how the game was played. He bowed to his mother, who did not get up—getting up was increasingly hard for her—and bowed a second and a third time, and said, without any sulking,

“Thank you for your gift, honored Mother. One was quite surprised.”

“You look very fine,” she said, looking extremely pleased. “How grown-up you look.”

“One is happy to be a fortunate age,” he said. “Thank you, honored Mother.”

There was, of course, tea. There were very fancy teacakes, one of a flavor he did not like, but his mother did, and he got it by accident. He took one bite, and nerved himself and swallowed the rest of it, smiling and washing it down with tea, thinking it was rather like the change of coats. One could get through anything, if there was a reason.

“The numbers of the day are fortunate,” she said. “And the whole country has turned out to celebrate the day, son of mine. The banners are out and the whole city will be in festival. You may see them from my windows.”

“I shall look,” he said. He truly had no desire even to go into the nursery, which had all the windows, but he thought perhaps he should, at least once, so when he had had his tea, he did go, and stood with his mother looking out past the filmy lace of the nursery windows. Very small and distant, there were colorful banners, and the tops of the tents, and the main street, even farther, crowded with people.

“The city is happy,” she said, with her hand on his shoulder, “and so should you be.”

“One is indeed happy,” he said dutifully, already wishing to be back in the sitting room. “One is very happy.”

“Your father favors you,” she said, and her fingers pressed his shoulder hard. “He favors you so extremely your sister will rely on you for the least scrap of his favor. Say to me that she will not go wanting.”

He did not look at her until one fast, wary glance, and she was gazing out the windows, into the hazy distance.

“I shall take care of my sister,” he said, and her hand pressed once, then relaxed. “Have I not told you I shall? If she relies on me, I shall be her older brother.”

“As you should be,” she said. “Always remember that.”

An uneasy thought struck him. “You will be here, will you not?”

“That is always at your father’s pleasure. But someday it will be at yours.”

“You are my mother,” he said with complete determination. “I only have one.”

“That is good to know,” she said. “Shall we return to the sitting room?”

He was only too glad to do that.

· · ·

Getting three kids into unfamiliar garments and giving them a meaningful lesson on how to keep the cuff lace out of the soup and the soup from landing on one’s collar lace was no small undertaking. Turn your wrist to the outside covered the first; and Keep your chin up was the other. They practiced with water, as less damaging than soup.

“Very well done,” Jase said. “I shall try not to be the one to have soup go astray. You all have your speeches, if you need them.”

“Yes, nandi,” Gene said, with a very proper bow. “And one will pay very close aggravation to persons.”

“Attention,” Bren corrected quietly. It was a very easy mistake. “Elegantly done, Gene-nadi.”

“Attention,” Gene repeated, a little chagrined. “Yes, sir.”

Bren set his hand on Gene’s shoulder. “You three are extraordinary. Keep up the manners just until midnight, and don’t panic if you make a mistake. You’re all three very small, people won’t possibly mistake you for adults, and while children have all kinds of leeway . . . everyone’s very impressed when they get things right. So just bow and apologize, and if you really have an accident, you have several spare shirts in my apartment. We can rescue you if we must, but we’d so much rather not. And the farther we get from the apartment the harder it becomes. Security’s extremely tight.”

“Yes, sir,” Gene said in ship-speak. “We won’t mess things up. We really won’t.”

“Good. Good.” Bren let the boy go and cast a look at Jase. “We’re about due. Dur’s just made it up to the floor. I need to go. If you can follow with the youngsters, we’ll expect you in about ten minutes. Kaplan and Polano are ready?”

“Suited up and ready,” Jase said. “We’ll be right over.”

“See you,” Bren said, and went out to the hall. Staff told staff, and his bodyguard showed up a moment later, Banichi with them, without his sling, at first glance, but then one noted the black, slim support for the injured arm.

Good for that, he thought. He had his hair arranged to hide the stitches, had a little paper of pills, not for atevi consumption, in his right pocket, and a second number of pills, not for human consumption, in the inside pocket of his dress coat, nicely done up, not to mention the discreet little pistol he had in his right-hand coat pocket . . . he had not carried it to the Guild. It did not mean he could not carry it to Tabini’s apartment.

“Nichi-ji,” he said as his aishid joined him. “We are agreed, are we not, each to take a rest as appropriate?”

“We are agreed,” Banichi said.

“Do we have a promise, Nichi-ji?”

“We have an agreement, Bren-ji.”

It was as good as he was getting. Narani opened the door for them, and they walked out and down the short distance to the aiji’s door—which, as it chanced, was still open, Lord Tatiseigi having just arrived with, as it proved, the aiji-dowager.

One simply stood a bit back and let that party sort itself out. There was some little hushed and prolonged to-do involving a coat, about which neither was pleased. But Ilisidi said, “It is the boy’s event, Tati-ji. He will wish not to affront his mother.”

“His mother,” Tatiseigi muttered, but said no more of it.

One didn’t ask. One was simply glad to get through the door, past the foyer, and into the enforced civilization of the dining room, where, indeed, the younger and the elder Dur were already present, and the formalities were a welcome relief.

The dining table was at full extent, with places for thirty-three persons, including Jase and the three youngsters, and an assortment of lords and spouses. It was diplomacy at full stretch. Even Lord Keimi had come in from Taiben—very, very rare that he put in a court appearance; but it was a pleasant arrival. Haijden and Maidin were there. And Jase and Cajeiri’s guests arrived, Jase resplendent in the borrowed coat and the youngsters in immaculate and proper court dress—shy, and a little hesitant about getting to seats, but Jase, who could read the name tags, settled them properly, and sat down in a seat of high rank next to Tatiseigi, who was family—with the youngsters at his left, as Cajeiri’s guests. As minors in Jase’s care, they were seated far higher than their rank would have allowed.

But good-natured Maidin was next to them, and Dur was across the table, which was a very deft bit of diplomacy. The servants brought a cushion for Irene—the boys being just the little degree taller that made a cushion a bit too much; and the youngsters sat with their hands tucked and their eyes darting about the glittering table and the glittering guests—very, very quiet, the three, on best behavior.