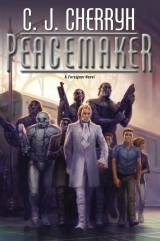

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Mani, Great-grandmother, had ordered a regular train to come to Tirnamardi’s rail station to pick them up, and it was interesting to see what an ordinary passenger car looked like inside—brown mostly, mostly enameled metal, and the seats were not nearly as comfortable as the red car his father kept. There were sets of seats, too, with tables between; he and his guests had one such set; his bodyguards, across the aisle, had another such set. But none of the seats had cushions.

The car was not armored, either, which was another reason they had to keep the shades down.

And while mani had told him they would all just go back to the Bujavid and go upstairs and have dinner in Great-uncle Tatiseigi’s apartment tonight—things were far from normal. Every promise was subject to change, and though they were trying to pretend things were normal, his three guests all knew there was trouble.

It was almost his birthday, he was almost nine, he should have had two more days at Tirnamardi, riding mecheiti and doing whatever he liked; and that had lasted about one whole day. He didn’t know exactly what danger was out beyond those window shades—except that Kadagidi clan was definitely upset, except that Banichi was hurt and some of Great-grandmother’s young men were, and except that they had the Kadagidi lord a prisoner in the next car, along with two Dojisigi Assassins, who had come to kill Great-uncle and had apparently ended up turning on the Kadagidi lord instead.

It was all about the Shadow Guild, which was scary bad news. He had so much rather it was just two lords fighting.

Mani had said everything was going very well—and he almost believed that, considering that they had apparently won, but mani had been very grim when she said it. And she had not wanted to wait for the safer, armored Red Train to travel out from the Bujavid—because speed was apparently more important than security. Or speed was security. The adults had not told him which. He almost had the feeling it was speed his great-grandmother wanted right now, not because she was running, but because she had somebody specific in her sights. She had that look she took on when she had a target. But he had no idea who that might be.

He, meanwhile, was in charge of his birthday guests, while the grown-ups did their grown-up business and laid plans and kept secrets. He had to explain the situation to his associates from the space station, and he—and his bodyguard—had to be very sure they didn’t sneak a look out past the window shades. Going out to Tirnamardi they had been more relaxed and they had done a lot of looking from the bus—but on the Red Train, they had had no windows to look out once they were aboard: its walls had only fake windows. In this car, there were just woven fabric shades between them and outside, and the temptation even for him was extreme. His guests were missing a chance to look at trees and the whole world that they had come down to see.

But along the way, among those trees, there could very well be Assassins waiting to shoot at them, because, as his bodyguard had told him, trains ran on tracks, and anybody could tell the route they were going to take.

Anybody could guess, too, that the Shadow Guild was going to be very upset about what had happened to some of their people this morning.

Had they left anybody behind who would be chasing them? His bodyguard said it was possible, but the senior Guild was not telling them that.

Officially, too, everybody acted as if he was still going to have his birthday party in the Bujavid, the way they had always planned. He was not entirely sure that was still the truth. But he was at least sure that the grown-ups were doing their best to keep them all alive, and he was not a baby, to think that his party mattered on that scale, even if the whole thing did make him mad.

Very mad.

He’d understood last year, when they’d arrived back on the world on his birthday and they had to sneak across country . . . he hadn’t been happy about it, but that was the way it had had to be.

So here they were sneaking across country this year, too. He had gotten his guests down from the space station. But their parents might not ever let them come back again, the way things were going. They might not want to come back, the way things were going.

Now his grandfather was dead, just north of Great-uncle’s estate . . . and nobody knew why.

He was sure that if anything had happened to his parents in Shejidan, his great-grandmother and everybody else would be a great deal more upset than they were, so everything was probably all right in the Bujavid—assuming the Bujavid was really where they were going, and it was not another trick for their enemies.

And if Great-grandmother was talking about dinner plans for him and his guests—it was even possible they were going to carry on just exactly as they had at Tirnamardi, with him keeping his guests happy, while Great-grandmother and all the adults were sending out people to do things that were going to make somebody else very unhappy.

All he and his guests had seen of the trouble so far was smoke on the horizon, and flakes of ash wafting down on the driveway at Tirnamardi. Well, that, and riders going back and forth in the night. And all of the goings-on with the Dojisigi Assassins.

It did seem odd to him that Great-uncle was not that mad at the two Dojisigi who had tried to kill him. Dojisigi clan had made trouble for everybody in the north for a hundred years at least, so they had been a problem for a long time, and the Atageini and the Dojisigi had never had any good dealings between them that he knew of.

But then so had the Dojisigi clan’s neighbors, the Taisigi, been a problem just as long, and now Lord Machigi of the Taisigi was Great-grandmother’s official ally.

And he did know that Dojisigi clan had had the Shadow Guild running their district for a long time, and then the regular Guild had come in and replaced the Dojisigi lord with a girl who was, his great-grandmother said, not fit to rule. So maybe Dojisigi clan as a whole had figured out that things were going to change, and wanted to ally with his great-grandmother just like Lord Machigi, before Lord Machigi got all the advantage and all the trade.

That was politics. One could just not say a thing would never happen or that somebody would be a problem forever. He had watched all sorts of really strange changes happen, almost all of them in his eighth year.

So one had to be ready for any sort of thing to change.

The hard part was, he was going to have to explain to his guests the politics of what was going on, without scaring them or mentioning things that could be his great-grandmother’s secrets. He was sure the fighting over on Kadagidi land was not going to be secret from the ship-folk, since Jase-aiji had been right in the middle of it. So the ship-aijiin were going to know a lot more about that situation than he could tell to anybody, since he had not been there.

And secondly—his three guests were not stupid, and they had seen most everything that had gone on over on Great-uncle’s estate, including the ashes falling on the driveway, and the smoke beyond the hedges and the bullet holes in the bus that had taken them to meet the train.

“So are we going to meet your parents when we get there?” Artur asked him.

Gene, Irene, and red-headed Artur—his three associates from the starship where he and Great-grandmother had lived for two years . . . well . . . his three associates whose home was now on the space station.

His three associates who were full of questions and who did not have enough Ragi words even to ask him what was going on.

They were not used to the way atevi lived, or what it meant to be Tabini-aiji’s son.

But they did understand politics and double-crosses. He knew that. Their own politics was trying to send all of them that had come back on the starship out to a new station over a dead planet, far away from the Earth, for a lot of really underhanded reasons, like people wanting political power and people not trusting one each other. That was one thing.

And his guests by no means wanted that to happen: they were scared to be shipped out to a lonely place where they could never come back again. So they had real reason to ignore anything bad about their visit and not mess things up.

And, he thought, they wanted to tie themselves to him as solidly as they could, not in a bad way, so far as he was concerned, even if it could be because they were afraid of being sent away to that other world. If they wanted favors, if they wanted things, that was all right. Giving them whatever they needed hardly hurt him. From his side—they were associates. His associates. He was who he was because he had important associates, and maybe three young people from the space station were not as important as, say, nand’ Bren or Lord Geigi, but he wanted as many good connections as he could get, and they made him feel—good—when he could give them things.

That was the way things were supposed to work, was it not? Humans called associates friends, which was the opposite of enemy, sort of, but in a disconnected sort of way, and he was not supposed to ask about that or use that word. Even nand’ Bren said it would confuse him and it could hurt him. And that it was a little early for trust, but that if it got to trust, it had to be true both ways.

He just knew he had to protect them and keep them happy. And since they were going back to the Bujavid, that began to mean keeping his father happy, above everything else. His father—and his mother.

“Will we stay with Lord Tatiseigi in Shejidan?” Irene asked, across the little table, beside Artur. “Where shall we go?”

“I don’t know,” he said. They were right to be worried. He was worried. His father could change directions very fast and his parents might want to talk to him, by himself, particularly to ask him what his great-grandmother was up to in all these things that had nothing to do with his guests—but as far as he knew, nobody had even told his parents yet that they were coming back early. “Probably we know soon. Definitely. Soon.” His mother was about to have a baby, his grandfather had just been assassinated for reasons nobody had quite figured out, and his father was not going to be in a good mood if his mother was out of sorts or if Great-grandmother had created a problem. And arresting the lord of the Kadagidi could be a problem. He was not sure he wanted his guests anywhere near his parents until that all settled down.

They might stay with nand’ Bren, maybe.

Except nand’ Bren might not have room. Nand’ Bren’s apartment was the smallest on the floor.

Great-grandmother’s apartment was possible. It was huge.

Everything had to solve itself soon. Even if they had just run into a life-and-death emergency about assassins and the whole world was going to be upset—his birthday was a certain date they could not move, which meant his birthday was going to be in the middle of whatever was going on.

If he was really going to have his birthday at all. He hardly remembered his fifth, and his seventh had happened around when they had reached Reunion, and Great-grandmother had just had a nice dinner later with his favorite things, with no celebration, not even nand’ Bren, and not even her attention, since she had spent the whole time planning something. And atevi did not celebrate the unlucky numbered birthdays at all. Humans did. They were reckless about numbers. But atevi never were.

So he really had no idea how his fortunate ninth birthday would turn out, except he was supposed to get good things, and he was supposed to have a good time. So far all the things about his birthday, like his present from Great-uncle, and having his three associates down from the station, and everybody being as nice to each other as could be—that had been enough to make him look forward to the real day . . . when he might, he understood, get new privileges. Being back in the Bujavid was going to be convenient, being where he could order things to give his guests—but not if Great-grandmother and his father and his mother were going to be fighting so they forgot all about his birthday.

But he could not go up to the adults and talk about his problems when people were hurt and when the adults were all talking about the Shadow Guild and the Kadagidi and serious troubles. No. He was supposed to be back here with his guests, pretending everything was normal.

It felt just like last year, when he had had his eighth birthday. His associates had told him he should get presents. He understood now it was polite to give them on his birthday, at least to special people; and that the really good thing on his birthday should be how people treated him, and what he was allowed to do. He liked that idea. It would be really good if what he got was permission to go about with just his guard . . . but he had not too much hope of that, with all that was going on.

Still, there might be something new he would be allowed to do. He hoped it was good.

His privilege-gift from Great-uncle was wonderful, and was an actual present, too—a mecheita descended from Great-grandmother’s famous Babsidi. And the privilege part of it was Great-uncle and mani believing he was old enough now to handle her. He had gotten that gift in front of his guests. And it had been the best day of his whole life.

Until it turned out someone had killed his grandfather, and the Kadagidi had tried to assassinate Great-uncle.

The sun sent a tantalizing shadow of something flickering across the shades.

“Don’t,” he said in ship-speak, as Irene glanced toward that window shade right beside her. She looked at him, a little startled, then embarrassed.

“I forgot.”

“One regrets,” he said in Ragi, in deliberate anger, in the most perfect court accent, “that we cannot open the shades. One regrets that we shall probably be indoors from now on. One very much regrets, nadiin-ji, that there is a stupid old man in the Guild.”

Probably they missed half of that. He had not been thinking about simple words. He had only felt he had to say it or explode. And he was sorry now he had let his voice be sharp.

“We’re fine,” Gene said in ship-speak. “We’re fine, Jeri-ji. We’re here. We’re on a planet. It’s ordinary to you. But we’ve never even seen a planet in our whole lives. Now we’ve seen trees. And we’ve been on mecheita. And we’ve seen all sorts of things. Just riding the train is exciting. We’re all right. We want you to have a good time. It’s your birthday.”

“That’s right,” Artur said. “Isn’t it, Irene?”

“We’re all fine,” Irene said. “We’re happy.”

They were very generous. He hoped they were enjoying at least what they could see. Everything had been different for them. And there would always be rules—there had been rules about manners at Great-uncle’s house, when what they all had most wanted was to remake the association they had had in the tunnels of the ship, when they had broken all the rules they ran into with no fear at all.

But it was all different, now. Here he was not Jeri-ji, the youngest of them. He was “young gentleman” and “young sir,” and they were, well, his guests, and he was in charge of them, and he had to protect them. He had tried to explain about the Kadagidi. But they had no idea even yet what was really going on, and how bad it could get if enemies were trying to attack his father and overthrow the government again.

Last night had not upset them that badly. They had not panicked. They had not asked to go back to the spaceport or wished they were back on the space station. They said were sorry about his grandfather—but they did not understand. They knew he was upset about his grandfather dying—but they thought it was from missing his grandfather. He thought about explaining the truth, that he was worried about whether his mother or father had ordered it, and how that would affect whether they stayed married.

But he was too embarrassed to explain that to them.

They could not be two years younger, and back on the ship. Then, they had all been strangers, and bored, and amused themselves by dodging the guards and doing things they were told not to do, harmless things, but forbidden things—like even seeing one another, and meeting in secret places. They were all of them older, now—smarter, more suspicious. They were all more political: that, too. Far more political.

And it was just a year that had passed. But so very much had gone on.

And if he understood what his guests had told him—most of the grown-ups that had let them come down to the planet had done it only in the hopes they would no longer get along, and that that would end the association for good.

He was sure that was why his parents had said yes to the idea.

He had figured that out early, without any help from anybody, the night after he had heard from his father that his associates from the ship were really going to be allowed to come.

His mother, who was really not in favor of humans at all, really, really hoped he and they would not get along. His mother already accused him of getting his ideas from nand’ Bren, as if that was bad—his father asked nand’ Bren’s opinion on a lot of things, so was that wrong?

He thought it was not.

His father might not quite be planning on them falling out with each other—but with his father, everything was politics, and maybe his father had notions of playing politics with the ship-captains, eventually, if it did work. At very least he was sure his father was just waiting to use the association, if it worked, or end the notion, if it failed.

But he had thought entirely enough about politics for one day. He just wanted his guests to want to come back again.

“Are you scared?” he asked, the old question they had used to ask each other, when they had been about to do something dangerous in the ship tunnels. “Are you scared?”

“Hell, no,” Gene laughed, the light-hearted old answer.

“Is it true, Gene-ji?” That was not the old question. “Are you scared? There was danger at Tirnamardi. There will be danger where I am, in Shejidan. Are you scared?”

“Are we stupid?” Gene asked with a little laugh. “We were scared when we got on the shuttle to come down here! Irene was so scared she threw up.”

“Don’t tell that!” Irene protested.

“But then she said,” Gene added, “‘It’s all right. I’m going!’ And here she is!”

“We’re all scared,” Artur said. “But Reunion Station was more scary. The kyo blew up half the station and we didn’t know when they were coming back to blow up the rest of it. We’ve got Captain Jase, we’ve got his guards with us, we’ve got your great-grandmother and nand’ Bren and Lord Tatiseigi, and all their bodyguards—not to mention your bodyguards. They’re scary, all on their own.”

Cajeiri had not quite thought of Antaro and Jegari, Lucasi and Veijico as scary, but he did think they looked impressive and official, now that they all wore black leather uniforms and carried sidearms.

“We don’t know that much about what’s going on,” Gene said, “but it doesn’t look like you’re scared. Are you?”

Cajeiri gave a little laugh, and measured a tiny little space with his fingers. Old joke, among them. “This much.”

They laughed out loud. All of a sudden, on this train full of trouble, they laughed the way they had used to laugh when things had gone wrong and then, for no good reason, gone right again.

It was the first time he had felt what he had been trying all along to feel about them, all the way through the visit to Great-uncle’s house.

They were his. They were together. They were all feeling what he felt.

He drew a deep breath and ducked his head a little, because mani and Lord Tatiseigi would not approve of an outburst of laughter from young fools. “Shh.” Most everybody was asleep, and no one used loud voices around his great-grandmother. Especially no one laughed when things were serious.

So they immediately tried to be quiet. Artur leaned his mouth against his fist and tried not to laugh. A breath escaped. Then a snort. Like a mecheita. Exactly like a mecheita. It was too much.

Cajeiri propped his elbows on their little table, joined his hands in front of his mouth and nose and tried not to make any sound at all approximating that snort. Gene and Irene were all but strangling.

They had not laughed like this since they had escaped the security sweep in the tunnels.

He was sure one of the grown-up Guild was going to come back to them and want to know what was going on.

Which only set his eyes to watering and made breathing difficult.

He tried to bring it under control. They all did. It only made it worse.

They were that tired. Nobody had gotten any sleep last night. And they laughed in little wheezes until their eyes watered.

It was a kindness when nand’ Bren’s two valets brought them tea and crackers. They were finally able, with moments of fracture, to quiet down, in the reverent silence of tea service.

“Sorry,” Gene said, and that almost started it all over, but deep breaths and hot sweet tea restored calm, finally.

There was a small silence, the wheels thumping along the iron track, unchanging.

“I want to do everything there is to do,” Irene said. “I want to see everything, taste everything, touch everything. I get dizzy sometimes, looking at the sky. But vids don’t do it, Jeri-ji. You have to feel the wind. You have to smell the green. It’s like hydroponics, only it’s everywhere, just growing where it wants to.”

“It was great,” Gene said.

“It’s going to be great,” Artur said. “It all is. Irene’s got it right. God, when Boji came climbing up that wall . . .”

“The Taibeni riding through,” Gene said.

“The storm,” Irene said on a deep breath. “The lightning was amazing. That was just amazing!”

4

Bren poured himself another half cup of tea, timing it to the gentle rock of the rails. The clack and rumble, that sound that was bringing them closer and closer to the capital, should be soporific. His body-servants were dozing, like almost everybody else on the train. The tea, however, didn’t in the least help him toward sleep.

But sleep had thus far eluded him, and he wanted warmth against a slight inner chill, and an exhaustion that, this afternoon, seemed to have no cure.

They’d killed people, this morning.

He’d set up the attack. He, Bren Cameron, clearly no longer working for the Mospheiran State Department, no longer just the aiji’s translator—he’d presided over a scene of devastation.

It wasn’t the first time he’d been in a firefight. But never one that so unexpectedly shook the ground, still reverberated in his bones, so out of place, so alien, in a place that never ought to have seen violence at all.

Lord Bren of Najida, it was, now. Paidhi-aiji, the aiji’s mediator. Lord of the Najida Peninsula. Lord of the Heavens—Tabini had had only the vaguest idea what was above the atmosphere when he’d conferred that title, but he’d sent the paidhi-aiji up there to deal with humans and he’d wanted to make damned sure the paidhi had whatever power it took to put him in charge of whatever he could lay claim to—in Tabini’s name, of course.

In one sense the title only amounted to a name, a piece of starry black ribbon on the rare occasions he chose to wear it; but in another sense it was Tabini-aiji’s declaration that atevi were a permanent presence up there in space, that they meant to have a say in what went on up there, and that their representative was going to have all the respect and backing Tabini could throw behind him.

Three some years ago, that had turned out to mean Tabini’s presence was going to go with humans out to deep space and back and find out whether what humans had told them about their situation as refugees was true—or not.

It had been a two-year voyage, one year out, one year back—and in their return they had brought thousands of colonists forcibly removed from their station, to be relocated on the space station above the Earth of the atevi. That was one problem.

And during their absence from the world, his, the heir’s, and the aiji-dowager’s—they had immediately met a bigger one: the situation back home had completely gone to hell and the government had come into the hands of Tabini’s enemies.

They hadn’t really had to right that situation at the outset: with a little encouragement, the people had set Tabini back in power.

Their investigation in the year since Tabini had resumed his place as aiji was only now uncovering what had really happened, and it hadn’t been what they had first thought—what he and most people had believed as fact as late as a few weeks ago: that the coup which had driven Tabini from power for two years had involved a discontented Kadagidi lord with Marid backing, who had somehow gotten together a band of malcontent lords and their bodyguards, penetrated the aiji’s security, seized the shuttles on the ground, and been able to throw the government into chaos, all because Tabini’s sliding public approval had hit rock bottom.

Wrong. Completely wrong. It hadn’t been in any sense public discontent with the economy—or with Tabini’s governance—that had overthrown his government and set Murini in charge.

It hadn’t even been Murini who’d actually plotted Tabini’s overthrow.

They’d assumed it had been Murini. There had indeed been a public approval crisis, in the economic upheaval of the push to get to space.

But none of these problems had really launched the attack on Tabini.

He’d been surprised, really shocked, how bravely and in what numbers ordinary people had turned out in droves to support Tabini’s return to power. Evidently, he’d thought at the time, the populace had had their fill of Murini. They’d changed their minds. They’d seen the dowager and the heir come back from space and they’d understood that humans had been telling the truth and dealing fairly with atevi, against all doomsaying opinions to the contrary.

That had brought the people out to support Tabini’s return. Mostly, he’d thought then—it had been a return to normalcy the crowds had cheered for, after things under Murini had gone so massively wrong.

There’d been discontent before Tabini’s fall, but no, it had not been lords riding a popular movement that had organized the coup.

It had not even been a small group of malcontent lords acting on their own, though one of them had been glad to take over, not understanding, himself, that he was only a figurehead.

No, it hadn’t been Murini who’d done it.

He and his bodyguard had gradually understood that, and begun to look for what was behind the coup.

His own bodyguard and the dowager’s, working together, had been pulling in intelligence very quietly, intelligence that required careful sifting—old associates making contact from retirement, giving them, as he now knew, a story completely at variance with the account they were still getting from other sources. Some individuals that they might have wanted to consult—Tabini’s bodyguard—were dead, replaced twice since. And every inquiry they made had, he knew now, run up against rules of procedure—within the closely held secrecy of the Assassins, the most secretive of Guilds.

His bodyguard, and the dowager’s, had protected him, protected the aiji, and protected the heir through some very dicey situations, including misinformation that had nearly gotten him killed out on the peninsula.

They’d survived that. They’d tested their channels. They’d quietly worked to ascertain who could be trusted . . . and who, either because they were following the rules, or because they were part of the problem . . . could not be relied on.

Geigi coming down to the world had been a major break. Geigi, resident on the space station during the whole interval, observing from orbit, had filled in some informational gaps; and he was sure Geigi had gotten an earful of information from his own bodyguard when he’d gone back up there.

So now Geigi had sent them the three children, a ship-captain, and two ship’s security with a bagful of gear they weren’t supposed to have, and in which his own bodyguard had to take rapid instruction.

It was a good thing. Their opposition, finding pieces of their organization being stripped away, was making moves of their own.

The Kadagidi setup—was major.

Done was done, now. The lid was off, or was coming off, even while this train rolled across the landscape. Those of them that opposed the Shadow Guild dared not rely on orders going only where they were intended. They could not rely on discretion. They could not trust Guild communications, or rely on any personnel whose man’chi his bodyguard or the dowager’s didn’t know and believe. The matter at the Kadagidi estate this morning had been Guild against Guild—they’d exposed the Shadow Guild’s plot to assassinate Lord Tatiseigi. But they’d also hit right at the heart of Shadow Guild operations inside Assassins’ Guild Headquarters.

The Shadow Guild, wounded, might think it was blind luck and an old feud that had guided the strike. It wasn’t. And whatever the Shadow Guild believed, it could figure their enemies had just gotten their hands on records. Whether or not the Shadow Guild believed they’d delivered an intentional blow straight at them—it was time for the rest of the Shadow Guild operation to move. Fast.

From their own view—the Assassins’ Guild might have seemed on the verge of fatal fracture, infiltrated at its highest levels, still shaken by fighting in the field against Southern Guild forces. People who guarded the aiji already felt themselves unable to rely on Guild lines of communication . . .

One assessing the aiji’s chances of survival might think that the infiltration might be pervasive, and fatal.

But now they knew it was not that the infiltration was pervasive through the Guild, no. It was that it was that high up. It was not the rank and file who could no longer be trusted, and it was not a widespread disaffection within Guild ranks. It was a problem in the upper levels that had been able to set a handful of people in convenient places, that had sown a little disinformation in more than one operation—and done an immense lot of damage over a very long period of time.