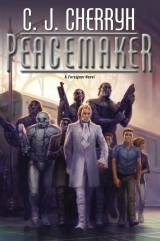

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“Nobody told me!”

“This was done for your benefit, son of mine. It is now done for the first time since your great-grandfather’s Investiture, from before the East joined the aishidi’tat. The kabiuteri are extremely pleased to have the custom renewed—ecstatic, to put it plainly—and they will find felicity in every syllable of your speech. Between us, the longer the speech, the more adorned with fortunate words and well-wishes, the more easily kabiuteri can find good omens in it. We have just resurrected a tradition one hopes you will maintain in your own day. And you may be quite proud of the distinction. Your great-grandmother is delighted.”

He supposed it was a great honor. He was glad if he had done well: he had tried to name nine people and give something good to everybody, the way his father had advised him, but he could hardly remember anything he had said except in generalities. Ever since Assassins had turned up at Great-uncle’s house, he had felt as if he was being shoved from every side in turn, scattering every thought he had—

Mani would not have forgotten everything she had just said. Mani never grew scattered. Mani always knew what mani wanted. She never forgot a thing.

So what had he said? He mostly wanted everybody to live for a long time, he wanted no more wars, and he wanted the world to be beautiful and peaceful . . . it was stupid that some people wanted the world neither beautiful nor peaceful.

He thought it was likely the same people his father and his great-grandmother wanted to be rid of.

So he supposed his mother was right, that he really was his great-grandmother’s, more than anybody’s.

“There will be cards to sign,” his father said, steering him off the last step and, yes, toward a long table set with flowers, where there were candles, one of which belonged to a waxjack: it was now lit; and there were rolls of ribbon and stacks of cards, and they were not going to get to eat.

“Shall I be signing, honored Father?”

“That you shall, a card for every person here. The ones given out in the city, some twenty-seven thousand of them, will lack a signature, but they will have a stamp and ribbon . . . you may sit beside me and sign your name first.”

He wished he had practiced his signature. He was still not satisfied with his signature and he was not used to doing it. He wanted a chance to change it someday. And maybe now he never could. And he had no seal ring, nothing like his father’s, which could make a seal official: he always used just a little wi’itikin stamp he had gotten, but it was a trinket, not a real seal, and he did not even have it with him. His pockets were empty. Just empty. It was a condition he was not at all used to.

He reached the table, where secretaries and officials bowed to him and his father, and their bodyguards took up position without being asked.

The oldest secretary, a man whose hair was all gray, arranged a little stack of cards to start with . . . in front of the black-draped chair at the end of the table.

“You need only sign here, young aiji, and pass the card to your father. He will sign it. Then we shall apply the seal and ribbons.”

His father said: “Take your time. Speak to the people.”

“Yes, honored Father.” He sat down on the edge of the seat. He tested the inkwell and the pen on a piece of blotting paper, and was glad the table was covered in black, so if he spilled ink, nobody would know.

And the first person in line was mani herself.

“We do not, as a rule, collect cards,” she said solemnly. “But we shall be very glad to display this one. Well done, Great-grandson.”

“Mani,” he said, and ducked his head: he hardly knew what to say. He signed his name and passed the card carefully to his father, who said, “Honored Grandmother,” and likewise signed it, passing it on to the secretaries, who would sand it and finish it with an official seal and red and black ribbons.

The next in line was Lord Tatiseigi. And the third was nand’ Bren. It was all very strange.

It was even stranger, when he signed a card for Jase-aiji, and a card apiece for Gene and Artur and Irene. “These are to keep,” he explained to Gene. “To remember.”

“We shall remember,” Gene said, and very shyly said, when his father signed the card next. “Thank you very much, nand’ aiji.”

It was the same with Artur and Irene. And then young Dur, Reijiri, came to the table.

“One is very glad you could come,” Cajeiri said, and meant it.

And to the elder Lord Dur: “It is a great honor you could come, nandi.”

“You are a credit, young aiji, you are a great credit.”

They were calling him not young gentleman, but young aiji. Were they supposed to call him that? His father had always said he was his heir. But was that somehow truer than it had ever been? Was that what his ninth birthday festivity meant, just because it was the fortunate ninth? Or was it because of that paper a messenger was carrying through the city?

Nobody had told him his ninth birthday would change everything.

Was he going to have to be like his father, now, and be serious all day, and sign papers and talk business to people? He wanted to go back to Great-uncle’s house and ride with his guests. That was what he wanted, more than anything . . .

But he was supposed to be thinking about people right now, being polite to lords his father needed him to impress, all these people in the hall, as many as he had ever seen in this hall at once.

And he smiled at those he knew and those he knew only by their colors. He was careful not to miss anybody. He thanked them for their good wishes, and meanwhile he could smell the food and knew everybody who left with a card was now free to go over to the buffet and have something to eat. He had not really eaten since breakfast, and a very little at the formal lunch.

But neither had his father. That was the way things were, if you were aiji.

It meant looking good, even if your stomach was empty.

· · ·

Was one justified in being personally just a little proud of the boy? Bren thought so.

Lord Tatiseigi was walking about with a glass of wine in hand and a smile on his face, and Ilisidi—Ilisidi was talking to the head of the Merchants’ Guild, very likely getting in a word or two about the Marid situation, doing politics as always, but looking extraordinarily relaxed and pleased.

Jase and the youngsters had been through the buffet, with small, safe cups of tea and a few safe sweets—the buffet would hold out for hours, and the alcohol had started to flow. Bren took sugared tea and a very manageable little half sandwich roll, stationing himself where he could watch the individuals he needed to watch.

Damiri had a cup of tea, and a congratulatory line of people—that could go on, and presumably it was going well. She had no part in her husband’s or her son’s card-signing, no formal part in the ceremony, but that was the way of things—the aiji-consort was not necessary in the inheritance. She was, legally speaking, not involved in the question.

One noted Tabini had mentioned his own mother in his address, and that was a first—a Taibeni woman, never acknowledged, never mentioned, not in Ilisidi’s favor, and for what he knew, no longer living. But if Ilisidi had taken any offense at that one mention, it was not in her expression at the moment.

Politics. Tabini had mentioned his Taibeni kinship tonight. The Guild, which had so obdurately found every excuse to ignore his Taibeni bodyguards . . . had just undergone a profound revision. Lord Keimi of Taiben was in attendance tonight: Cajeiri’s other great-grand-uncle had just, after two hundred years of war, signed a peace with Lord Tatiseigi.

The aiji-consort’s clan was as absent as the Kadagidi, the proven traitors. Cajeiri had been the one to acknowledge his own mother—Tabini had not mentioned her; but then, by the lines of inheritance he was reciting, no, he not only had not, he could not have mentioned her. It just was not the way things were done. It was up to her son to acknowledge her.

And he had. Thank God he had. Had Tabini urged him to it?

Likely. Tabini was trying hard to keep Damiri by him, no matter the increasing problems of that relationship. Tatiseigi likewise was doing his best by that relationship, ignoring Damiri’s flirtation with Ajuri.

The Ajuri banner had been prominent at the side of the hall tonight, for anyone who looked for it. The Kadagidi banner was not present. And there was only one person who could have made the decision to allow the Ajuri banner, given Lord Komaji’s banishment.

Tabini.

The banner had been here; but Damiri had not worn its brilliant red and gold this evening, just a pale green pleated satin that accommodated her condition, a color not quite saying Atageini, but suggesting it. Her choice?

Perhaps it had been her choice, on an evening where she had no official part. It was at least—politic. Damiri stood in a circle of lamplight, attended by Ilisidi’s guards, wished well by her husband’s associates, on the evening her son received sole title to her husband’s inheritance. And nowhere in Ragi culture did a lord’s consort, male or female, have any part, where it came to clan rights and inheritable privilege—it was just the way of things.

Tell that to Ilisidi, who had stepped forward twice to claim the regency, and to sue before the legislature simply to take the Ragi inheritance as her own. He had never quite appreciated the audacity of that move.

But then—Damiri had not been running half the continent before her marriage, and was not in charge of the spoiled, immature boy Valasi had reputedly been at his father’s death, a boy who had never, moreover, had an Investiture . . . nor allowed one for Tabini.

One could see . . . a decided difference in situations: Ilisidi, already ruler of half the sole continent, versus Damiri, the inconvenient offspring of a peacemaking interclan marriage gone very wrong—in a marriage some were saying, now, was becoming inconvenient.

Damiri, carrying an inconvenient surplus child, with her father’s clan very close to being dissolved for Shishogi’s treason, was not in an enviable situation, should Tabini divorce her. The only thing that prevented a public furor about another of Ajuri’s misdeeds was the Guild’s deep secrecy: it would swallow the person and the name of Shishogi so very deeply not even Ajuri clan might ever know the extent of his crimes—or even that he had died in disgrace.

Just a very few people inside Ajuri had to be asking themselves what they were to do with what they knew, and where on earth they would be safe.

Tabini didn’t want her taking on that lordship, for very good reasons. And there went her one chance of becoming a lord in her own right, setting herself in any remote sense on an equal footing with Ilisidi.

“Bren-ji,” Jago said, and nodded toward the east corner.

There was the service corridor. And Tatiseigi was positioned nicely by the dowager’s side, not likely to leave her now, and Damiri was fully occupied with well-wishers. The major ceremony was past. It was a good time to go aside and take a break—most of all to let Banichi take a rest, he thought. He yielded and went in that direction: the door was open, the hallway only dimly lit, letting people supplying the buffet and bringing back dishes get in and out of the hall without a disturbing flare of light.

The promised chairs were there. It was, indeed, a relief. He sat down. Banichi dutifully did the same.

“How are you faring?” he asked Banichi.

“Well enough,” Banichi said. “There is, indeed, no need.”

“Of course not,” Jago said.

Bren let go a long, slow breath. “He did very well, did he not?”

“He did excellently well,” Tano said.

“How is the city faring?” he asked, wondering if information was indeed getting through channels.

“Very well,” Tano said. “Very well indeed . . . a little damage here and there, simply the press of people. A bar set a television in a window, and attempted to serve drink on the walkway, and there was a complaint of disorderly conduct—it was nothing. The cards are still being distributed, from several points, and those lines are orderly.”

It was nothing. That was so much better a report than they could have feared. Algini scoured up a carafe of tea, and they kept themselves out of the way of serving staff coming and going.

“The runner has reached the Archive,” Jago remarked, listening to communications. And then: “Attendees in the hall have become curious about Jase’s bodyguard. They have stayed quite still. Cenedi has sent guards to protect them.”

One could only imagine, should Kaplan or Polano grow restless and switch on a light or two. Or move. “Jase says they can rest in there fairly comfortably,” Bren said, “with the armor locked. One cannot imagine it is that comfortable over time.” He drew a deep breath. “And I should get back to the hall, nadiin-ji. Banichi, can you not sit here with Jago a while? There is absolutely no problem out there.”

Banichi drew a deep breath. “Best I move, Bren-ji.” He shoved himself to his feet and drew a second breath.

“We may find an opportunity to quit the hall early,” Bren said, “all the same. We have done what we need to do.”

He walked out into the hall, and indeed, Tabini-aiji and Cajeiri had finished their card-signing and finally had leisure to talk and visit with well-wishers.

“Bren.” Jase overtook them, and Bren turned slightly, nodded a hello to Jase and Cajeiri’s young guests.

“So,” he said in ship-speak, “are you three managing to enjoy yourselves?”

“Really, yes, sir,” Gene said.

“We love the clothes,” Irene said. “And we got our own cards.”

“Treasure them,” he said. “You won’t find their like again in a lifetime. Onworld, they’re quite valuable.”

“Do we call him Cajeiri-aiji now, sir?” Artur asked.

“That is a question,” Bren said, and glanced at Banichi. “What does one call our young gentleman now?”

“‘Young gentleman’ is still appropriate,” Banichi said, “but Cajeiri-aiji, on formal occasions; or nand’ aiji, the same address as to his father.”

“Can we still call him Jeri?” Gene asked.

“Not in public,” Bren said. “Never in public. Never speaking about him. He’ll always be Cajeiri-aiji when you’re talking about him. Or the young aiji. Or the young gentleman. But what he is in private—he’ll define that.”

“Yes, sir,” Gene said. And bowed and changed back to Ragi. “Nandi.”

“Jase-aiji.” Bren gave a little nod and walked on toward the dowager, who had gotten a chair, likely from the other service passage, and who was quite successfully holding court over near the dais, with a cup of tea in her hands and a semicircle of attendance, including Lord Dur and Lord Tatiseigi.

Protected, still. He was satisfied. He turned the other direction, to let that gathering take its course, and to let that pair pursue necessary politics, and saw, at a little remove, Lord Topari.

That was not a meeting he wanted at the moment. He veered further right.

And found himself facing, at a little remove, the aiji-consort and her borrowed bodyguard.

She was looking right at him. Eyes had met. Courtesy dictated that he bow, then turn aside, but when he lifted his head, she was headed right toward him with intent, and etiquette demanded he stand there, bow a bit more deeply as she arrived, and offer a polite greeting.

“Daja-ma,” he said pleasantly.

“Are you pleased?” she asked outright.

“One is pleased that your son is so honored, daja-ma. One hopes you are enjoying the evening.”

“Is that a concern?”

She was set on an argument, and he was equally determined to avoid it. He bowed a third time, not meeting her eyes, not accepting a confrontation.

“My question was sincere, daja-ma. One apologizes if it gave offense.”

“Who killed my father?”

He did look at her, with a sharp intake of breath. “I did not, daja-ma, nor did the aiji-dowager, nor did Lord Tatiseigi, who would have received your father had he reached Tirnamardi. It is my unsupported opinion, daja-ma, that Tirnamardi is exactly where your father was going, and that the most likely person to have prevented him getting there was his uncle—your own great-uncle. Shishogi.”

Her eyes flashed, twice, luminous as they caught the light. “What do you know?”

“A question for us both, daja-ma: what do you know of him?”

“That you killed him.”

“I never met him. Nor did my aishid, in that context.” He saw her breathing very rapidly. “Daja-ma, are you well? There is a chair in the servant passage.”

“Why would he kill my father?”

“Do you know, daja-ma, who your uncle was?”

“That is a very strange question.”

He was acutely conscious of his own aishid, of the dowager’s men at Damiri’s back, of a crowded hall, though they were in a clear area. “There are things that I cannot discuss here, daja-ma, but that your husband surely knows.”

“Did he assassinate my father?”

“Daja-ma, your husband believed he protected you in dismissing your father, who was under pressures we do not accurately know. But to my knowledge the aiji did not wish his death. Your father may have discovered things he may have finally decided to pass to Lord Tatiseigi, as the closest to the aiji he could reach.”

“I am weary of riddles and suppositions! Tell me what you know, not what you guess!”

“Daja-ma.” He lowered his voice as much as possible. “We are not in a safe place. If you will discuss this with some person of close connection to you, one suggests Lord Tatiseigi.”

“The dowager’s closest ally!”

“But a man of impeccable honesty, daja-ma.”

“No! No, I insist on the truth from you. You advise my husband. And I am set at distance. I am told I shall not be permitted to leave the Bujavid. I cannot claim the Ajuri lordship. I cannot go to my own home!”

“Daja-ma, there are reasons.”

“Reasons!”

“Your great-uncle, daja-ma.” He kept his voice as low as possible. “I believe he did order your father’s assassination. If you wish my opinion of events, daja-ma, your great-uncle plotted a coup from the hour of your son’s birth. When the aiji sent him to the space station, out of reach, and in the dowager’s keeping, it so upset your great-uncle’s plans he launched the coup to remove the aiji, and possibly to appoint you to a regency until the succession could be worked out. But you fled with your husband.”

Her look was at first indignant, then entirely shocked.

“You had no idea, did you not, daja-ma?”

“This is insane! My great-uncle. My great-uncle is in the Guild.”

“He was in the Guild. Exactly so. And not of minor rank.”

“Ajuri is a minor clan!”

“That is no impediment. What would you have done, daja-ma, if the Guild had separated you from your husband and asked you to govern for a few months—or to marry—in a few months, for the good of the aishidi’tat.”

“You are quite out of your mind!”

“Did anyone approach you with such an idea, daja-ma?”

“Never!”

“Perhaps I am mistaken. But I am not mistaken about your great-uncle’s support—with others—of a Kadagidi with southern ties, to take the aijinate. And one is not mistaken in the subsequent actions of your great-uncle, whose subversion of the Guild created chaos and upset in the aishidi’tat, setting region against region, constantly hunting your husband, and then trying to seize your son. A great deal of what went on out on the west coast was aimed at removing me, and the aiji-dowager—and, again, in laying hands on your son. We had no idea at the time. Your husband declined to bring his son back to the Bujavid, preferring to confront these people in the field rather than in the halls of the Bujavid. What he feared in the Bujavid—I do not know. But it was substantial.”

She stared at him in shock, a hand to her heart. And he was sorry. He was intensely sorry for pressing, but it was, there in a quiet nook of her son’s Investiture, surrounded by his aishid and the dowager’s men, the same question that had hung over her marriage, her acceptance in her husband’s household.

“Your father had just become lord of Ajuri,” he said, unrelenting, “in the death of your uncle. There were, one fears, questions about that replacement which I had not heard—about which your husband may have been aware. The Guild was even then systematically withholding information from your husband’s bodyguard, on the excuse that he had appointed them outside the Guild system. The heads of the Guild knowingly put your household at risk with their politics, of which, at that time, your great-uncle was definitely part. The Guild also withheld information from my aishid—more than policy, I now suspect, in a deliberate act which put my life in danger and almost killed your son. There was a great deal amiss on the west coast . . . but the threads of it have run back to the Guild in Shejidan. Realizing that, the aiji-dowager’s aishid and mine began to ask questions, and to investigate matters inside the Guild, which, indeed, involved your great-uncle. He is now dead. Unfortunately we do not believe all his agents in the field are dead. So there is a reason, daja-ma, that the aiji has forbidden you to take the Ajuri lordship. There is a reason he, yes, questioned your clan’s man’chi and wanted your father and his bodyguard out of the Bujavid, and you safe within it. And you should also know, daja-ma, that the aiji has since then strongly rejected all suggestions that your marriage should be dissolved for political convenience, insisting that you were not complicit in your great-uncle’s actions. More, by retaining you as his wife, he has now placed you in a position which, until now, only the aiji-dowager has held. The aiji-dowager has questioned your motives. And I have begun to incline toward the aiji-dowager’s opinion—that you are independent of your late great-uncle, independent also of your father, your aunt, and your cousin, and also of your great-uncle Tatiseigi. You never courted power. But power may someday land in your hands. And at very least, throughout your life, you will find not only your son, but your daughter besieged by ambitious clans. You have strongly resisted the aiji-dowager’s influence. But, baji-naji, you could one day become her. Do not reject her or her allies. Learn from her. That is my unsolicited advice, aiji-ma. Now you have heard it.”

She was breathing hard as any runner. She stared at him wide-eyed in shock, saying nothing, and now he wished he had not thrown so much information at her, not all at once, not here, not—tonight.

“One apologizes, daja-ma. One truly does.”

“You are telling me the truth,” she said, as if it were some surprise. “You are telling me the truth, are you not, nandi?”

“I have told you the truth, daja-ma. Perhaps too much of it.”

“No,” she said, eyes flashing. “No, nandi, not too much. Finally, someone makes sense!”

“One at least apologizes for doing so here, daja-ma. Understand, too, your husband held these matters only in bits and pieces. None of us knew until a handful of days ago.”

“Paidhi,” she said, winced, breathing hard, and suddenly caught at his arm.

“Daja-ma!” He lent support, he held on, not knowing where or how to take hold of her, and Jago intervened, flinging an arm about her, holding her up.

“I think—” Damiri said, still somewhat bent. “I think I am having the baby.”

“The service passage,” Banichi said. “Gini-ji, advise security; advise the aiji.”

“What shall we do?” Bren asked, his own heart racing. “Is nand’ Siegi here?”

“Call my physician,” Damiri said, and managed to straighten. “I shall walk. There will be time. First tell my husband. Then call my physician.”

“Two of you stay with her,” Algini said to Damiri’s security: “The other go privately advise the aiji and stand by for his orders. Bren-ji, stay with us.”

Never complicate security’s job. He understood. They walked at a sedate pace, Damiri walking on her own, quietly taking Algini’s direction toward the service passage, past a number of people who gave their passage a mildly curious stare.

No one delayed them. They reached the doorway of the service passage, met servants exiting with food service, who ducked out of the way, startled.

“There is a chair, daja-ma,” Bren said, “should you wish. You might sit down and let us call help.”

“No,” Damiri said shortly. “No! We shall not stop. Call my maid. Call my physician!”

“Security is doing that, nandi,” Jago said quietly. Banichi continued to talk to someone on com, and Algini had eased ahead of them—he was up at an intersection of the corridor, giving orders to a uniformed Bujavid staffer, probably part of the kitchen crew.

“We have a lift car on hold,” Tano said.

“I am perfectly well, now,” Damiri said. “I shall be perfectly fine.”

One hoped. One sincerely hoped.

· · ·

They had finished the cards. Cajeiri’s fingers ached, he had signed so many, and toward the end he had begun simplifying his signature, because his hand forgot where it was supposed to be going.

He wanted to go find his guests and at least talk to them, and ask how they were doing; and he wanted to go over to the buffet and get at least one of the teacakes he had seen on people’s plates, and a drink. He very much wanted a drink of something, be it tea or just cold water. His throat was dry from saying, over and over again, “Thank you, nandi. One is very appreciative of the sentiment, nandi. One has never visited there, but one would very much enjoy it . . .” And those were the easy ones. The several who had wanted to impress him with their district’s export were worse. He had acquired a few small gifts, too, which his bodyguard said he should not open, but which would go through security.

Mostly he just wanted to get a drink of water, but the last person in line had engaged his father, now, and wanted to talk. He stood near the table and waited. And when his father’s bodyguard did nothing to break his father free of the person, he turned to Antaro and said, very quietly, “Taro-ji, please bring me a drink of something, tea, juice, water, one hardly cares.”

“Yes,” she said, and started to slip away; but then senior Guild arrived, two men so brusque and sudden Antaro moved her hand to her gun and froze where she stood, in front of him; the other three closed about him.

It was his father the two aimed at; but his father’s guard opened up and let them through, and then he realized, past the near glare of an oil lamp, that they were his mother’s bodyguard.

“They are Mother’s,” he said, which was to say, Great-grandmother’s. And they were upset. “Taro-ji, they are Mother’s guard. Something is wrong.”

“We are not receiving,” Veijico reminded him, staying close with him as he followed Antaro into his father’s vicinity.

“Son of mine,” his father said, “your mother is going upstairs. It may be the baby. She has called for her physician. We are obliged to go, quickly.”

“Is she all right?” he blurted out.

“Most probably. She has chosen not to go to the Bujavid clinic. She is giving directions. Nand’ Bren is with her. Your great-grandmother has heard. She will make the announcement in the hall.” His father set a hand on his shoulder. “Do not be distressed, son of mine. Likely everything is all right. We must just leave the hall and go upstairs.”

“My guests,” he said.

His father drew in a breath and spoke to his more senior bodyguard. “Go to Jase-aiji. Assist him and the young guests to get to Lord Tatiseigi’s apartment. Advise my grandmother to take my place in the hall. She may give the excuse of the consort’s condition. —Son of mine?”

“Honored Father.”

“Will you wish to go with nand’ Jase, or to go with us?”

He had never been handed such a choice. He had no idea which was right. Then he did know. “I should go where my mother is,” he said. “Jase-aiji will take care of my guests.”

“Indeed,” his father said, and gave a little nod. “Indeed. Come with me. Quickly.”

He snagged Jegari by the arm. “Go apologize to my guests. Tell them all of this, Gari-ji.”

“Yes,” Jegari said, and headed off through the crowd as quickly as he could.

Only then he thought . . . What about Kaplan and Polano?

· · ·

* * *

· · ·

The Bujavid staffer guided them through a succession of three service corridors, to a door that let out across from the lifts, in an area of hall cordoned off by red rope, and Guild were waiting beside a lift with the doors held open. Recent events still urged caution—but, “Clear,” Banichi said, and they went, at Damiri’s pace, which was brisk enough.

“We are in contact with the physician,” Tano said in a low voice, “but he is down in the hotel district, attempting to get to the steps through the crowd. Guild is escorting him. They will activate the tramway to bring him up.”

It was moderately good news. “Should we,” Bren ventured to ask Damiri, as they entered the lift, “call nand’ Siegi in the interim, daja-ma?”

She drew in a deep breath. They were all in. The door of the car shut, and Tano used his key and punched buttons. The car moved in express mode.

Damiri gasped and reached out, seizing Bren’s arm, and Algini’s, and they reached to hold her up.

“I think,” she said, “I think—”

“Daja-ma?”

“Get my husband!”

“We have sent word,” Bren said. “He is coming, daja-ma.”

“Are you sure?” she asked, and gasped as the car stopped. “Paidhi, he is not going to be in time.”

“Just a little further,” Banichi said. “We can carry you if you wish, nandi.”

“No,” she said, and took a step, and two. They exited the car into the hall, with a long, long walk ahead.

“Tano-ji, go to nand’ Tatiseigi’s apartment,” Bren said, still supporting Damiri on his arm. “Tell Madam Saidin to come. And nand’ Siegi if you can find him.”

Damiri opened her mouth to say something. And kept walking, but with difficulty. One truly, truly had no idea what to do, except to help her do what she had determined to do.

Banichi, who did not have use of one arm, moved to assist on the side he could, and Algini gave place to him. He said, quietly, “We are in contact with your staff, nandi, and Madam Saidin is on her way. So is your physician, at all speed. Here is nand’ Bren’s apartment. We could stop here, should you need. He has an excellent guest room.”

“No,” she said, but quietly, in the tenor of Banichi’s calm, low voice. “I shall make it. I can make it.”