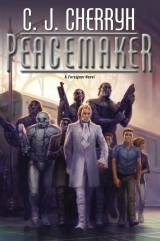

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Now they knew names. The dowager’s bodyguard, and his own, were increasingly sure they knew names, both good and bad. And the dowager intended a fix for the problem—granted they got to Shejidan in one piece, granted they could muster the right people in the next critical hours, and granted they did not muster up one wrong name among the others, or bet their lives and the aiji’s safety on a piece of misdirection.

They finally knew the Name behind the other names. They knew how he had worked. He was not an extraordinarily adept agent in the field, but a little old man at a desk.

His bodyguard months ago had reported the problem of tarnished names that deserved clearing—some living, some dead. A large number of senior Guild had retired two years ago, some of whom had dereliction of duty, medically unfit, and, in some cases, he was informed, even the word treason attached to their records. Some notations had landed there as a result of their resignations during Murini’s investigation, some had been added as a result of Tabini’s investigation into the coup and their refusal to be contacted. It had been disturbing—but credible—that persons who had never felt attached to Tabini and who were approaching retirement might just neglect to report back and go through the paperwork and the process after his return to power. Perhaps, the thought had been, these individuals had never appealed the matter or shown up in Shejidan to answer questions and have their records cleared . . . because they were just disaffected from the Guild itself, disillusioned and still angry over the handling of the whole matter.

Senior officers of the Guild had deserted in droves when Murini had taken over the government; they remained, his bodyguard had said, disaffected from current Guild leadership, opposing changes in policy. There was also old business, a lengthy list of Missing still on the Requests for Action which pertained to every Guildsman in the field: if one happened to find such a person, one was to report the location, ascertain the status if possible, request the individual to contact Guild Headquarters and fill out the paperwork—so Algini said. But there was, since Tabini’s return, no urgency on that item, Algini also said, and in the feeling that there might be some faults some of these members were worried about, there was a tacit understanding that nobody was really going to carry out that order. Some junior might, if he was a fool, but otherwise that list just existed, and nobody was going to knock on a door and insist a former member report himself and accept what might be disciplinary action. Certain members had left to pursue private lives under changed names.

A message had come from two former Guild Council members, stating that, in a new age of cooperation with humans and atevi presence on the space station, the old senior leadership felt themselves at the end of their usefulness. It was a new world. Let the young ones sit in council. With marks against their names, with records tainted, who knew what was true, or which of them to trust? They were not anxious to come back to hunt down other Guild. The idea disgusted them. They disapproved of the investigation and refused to submit to a Guild inquiry.

That was the only quasi-official answer to the demands of the infamous list that the Guild referred to as the Missing and the Dead.

The stalemate still continued. Those on the list would not answer a summons or account for their movements during the coup. The list was a farce and an insult. The reconstituted records, they said, were corrupt. They would not divulge information that might reveal contacts or the location of fellow Missing.

And, no, they would not come back. And they would not ask Tabini to be included in the amnesty afforded other guilds and given on a case-by-case basis to the Assassins. They maintained the executive branch had no authority to intervene in the guilds and that the list violated that principle. It was principle.

There had been a few resignations since the events out at Najida. The list had grown a bit.

Angry resignations, his aishid said.

And his aishid, and the dowager’s, had kept investigating . . . month after month. Tabini’s aishid, however, couldn’t. The current Guild Council refused to grant those four, who were Taibeni clan, Tabini’s remote cousins, any higher rank or a security clearance, because Tabini, of the executive of the aishidi’tat, had ignored the Guild’s recommendation for his bodyguard, and chosen his own, who were not classified as having a security clearance, or even advanced training.

It had been more than inconvenient. It had been damned dangerous . . . so much so that the aiji-dowager had finally ordered part of her own bodyguard to go into Tabini’s service and back up and train the four Tabini had appointed. The Guild knew about the four new bodyguards: nobody had officially mentioned the training part of the arrangement, which was, under Guild rules, illegal.

Things had gotten that bad.

Then, even as they’d sent Geigi aloft and into safety—Algini had come to him with information that made it all make sense.

So he knew things that no outsider to the Guild was supposed to know: he knew, the dowager knew, and Lord Tatiseigi knew. Young Cajeiri also knew—at least on his level—since his bodyguard meshed with theirs, and they all were under fire, so to speak, all of them and Tabini-aiji at once . . .

Because they knew exactly where the origin of the coup was, now. It had been no conspiracy of the lords, no dissent among the people. It was within the Assassins’ Guild. In effect, the guild that served as the law enforcement agency had fractured, and part of it had seized the government, setting it in the hands of a man who never should have held office.

The aiji-dowager and Tabini-aiji had started to correct matters by hunting down Murini; but after they’d taken down Murini, the problems had continued. They’d found themselves fighting against a splinter of the Guild they had naturally taken for Murini’s die-hard supporters. But defeating the Shadow Guild in the field had turned up a simple fact: the majority of those fighting Tabini in that action had been lied to, misled, and deceived. They might not have been innocent of wrongdoing, perhaps—there were orders they never should have followed. But their attack against the aiji’s forces had been under orders which turned out to have been forgeries, with no name that proved accurate, or that could be proven accurate.

That was when the dowager had known for certain that not everything wrong in the aishidi’tat had Murini’s name on it.

The legitimate Assassins’ Guild held its own secrets close as always—and, apart from its problem with disaffected senior officers refusing to debrief, or even to report in, their relations with the aiji had gone along at standoff regarding his personal bodyguard. It had seemed business as usual with the Guild.

And to this very hour Tabini-aiji was having to get his high-level information from his grandmother, who had the most senior team in the Guild—and Tabini still had to inform his own young bodyguard of what they should have been able to tell him.

To this hour, even a year after Tabini had regained power, they were still working to reconstruct what had happened the day of the coup, hour by hour, inside Guild headquarters and down their lines of communication . . . trying to find out where the problems still might be entrenched.

They had gathered information, they hoped, without triggering alarms.

This much they had been able to find out, and to stamp as true and reliable.

The day of the coup, a quarter hour after the attack on Tabini’s Bujavid residence, an odd gathering. . . . the lord of the Senjin Marid, the lord of little Bura clan from the west coast, the head of Tosuri clan, from the southern mountains, and four elderly Conservatives who should have known better . . . had officially declared man’chi to Murini and set him in Tabini’s place. It was exactly that sequence of events, that particular assemblage of individuals, and the rapid flow of information that had gotten them to the point of declaring Tabini dead, that had begun to provide their own investigation the first clues, the first chink in the monolith of non-information.

Those individuals—three scoundrels and four well-intentioned old men of the traditional persuasion—had probably all believed what they were told by a certain Assassins’ Guild officer, who had gotten his information from a source who credibly denied he had given it. These seven were told, the Conservative lords all swore to it, that Tabini was dead and that a widespread conspiracy was underway, a cabal of Liberal lords that would throw the continent into chaos and expose them to whatever mischief humans up in space intended.

These gentlemen were told that they had to subscribe to the new regime quickly and publicly, and make a statement backing Murini of the Kadagidi as aiji, in order to forestall a total collapse of the government.

It had certainly been a little embarrassing to them when the announcement had turned out to be premature: Tabini was alive. But the second attack, out in forested Taiben, was supposed to have taken care of that problem within the hour. That attack cost Tabini his original bodyguard, but it failed to kill him—and no one had told the honest elderly gentlemen who had backed Murini that fact, either.

Where did anyone later check out the facts of an event like . . . who was behind an assassination? One naturally asked the Assassins’ Guild.

The splinter group that they had come to call the Shadow Guild—to distinguish it from the legitimate Assassins’ Guild—had violated every one of those centuries-old rules of procedure and law that Wilson had written about in his essay. And down to this hour of the coup, the legitimate Guild, trying to preserve the lives of the lords who were the backbone and structure of the aishidi’tat, were still devoutly following the rulebook, as a case of—as Mospheirans would put it: if we violate the rules trying to take down the violators—what do we have left?

So at the start of it all—in those critical hours when Tabini was first supposed to have been killed in an attack on his Bujavid residence—the legitimate Assassins’ Guild had mistakenly taken its orders from the conspirators.

On news that, no, Tabini was alive, then, an hour later, killed in Taiben, they had again taken orders from their superiors and from Murini—not even yet understanding the whole architecture of the problem, or realizing that among these people whose orders they trusted were the very conspirators who were hunting Tabini and Damiri.

Within three more hours, however, legitimate Guild who suspected something was seriously amiss in their own ranks had begun gathering in the shadows, not approving of the new aiji’s initial orders or the conduct of the Guild as it was being run. They had evidently had particularly bad feelings about which units were being sent to search the Taibeni woods, and which were being held back.

They had had bad feelings about the recklessness with which the space shuttles and facilities on the ground were seized.

Then the units that had gone in so heavy-handedly to seize the spaceport were withdrawn in favor of more junior units who knew absolutely nothing about the technology, which made no sense to these senior officers, either.

These officers had taken even greater alarm when, that evening, assassinations were ordered without due process or proof of guilt, and senior Guild objections were not only ruled out of order—several were arrested, and their records marked for it.

The hell of it still was—the leadership of the conspiracy in that moment, even Murini himself, did not appear to have had a clear-cut program, or any particular reason for overthrowing the government, except a general discontent with the world as it had come to be and the fact that the leadership of the coup wished humans had never existed. A committee of scoundrels and confused elder lords had appointed Murini to be aiji—as a way, they said, to secure the consent of the influential and ancient Kadagidi clan to govern, and to spread a sense of legitimacy on the government. But they had not actually chosen Murini. Murini had been set before them as the choice—by a message from somewhere inside the Guild, the origin of which no one now could trace.

Murini had been, in fact, a very bad choice for the conspirators. He was a man mostly defined by his ambition, by his animosities, by his jealousies and suspicions. He’d come into office with a sense of entitlement and a set of private feuds he had immediately set about satisfying, under the illusion that he was the supreme power . . . and to make matters worse, the Shadow Guild under his authority hadn’t questioned his orders.

The Shadow Guild above Murini’s authority hadn’t apparently seen any urgency about stopping his personal vendettas, either—except to restrain him from attacking his two neighbors in the Padi Valley, the Taibeni and Lord Tatiseigi. Attacks on those two lords most loyal to Tabini would have raised questions about Murini’s motives as the defender of order and the savior of the Conservatives of the aishidi’tat: so the Guild serving Murini had kept him from that folly.

But his handlers seemed otherwise resolved to let him run his course and do in any people who argued with him.

Then once the legislature was filled with new and frightened faces, with a handful of Tabini’s longtime political opponents—and once the rest of the continent was too shattered to raise a real threat—one could surmise the people really in charge would quietly do in Murini and replace the villain everyone loathed with someone a bit more—personable.

Maybe that had been the overall plan. Or maybe there had never been a plan. Now that one had an idea of the personality at the core of it all, one wondered if the architect of the plot, the hidden Strategist of the Shadow Guild, had had any clear idea what the outcome could be, with all the myriad changes that had come on the world. The Strategist, a little old clerical officer named Shishogi, had probably had an idea and a design in the beginning of his decades-long maneuvers, but one wasn’t sure that it hadn’t all fallen by the wayside, as the world changed and the heavens became far more complicated than a bright blue shell with obedient clockwork stars.

Shishogi of Ajuri clan, in a clerical office of the Assassins’ Guild—a genius, perhaps—had started plotting and arranging to change the direction of the government forty-two years ago—and the situation he’d envisioned had long since ceased to be possible, let alone practical. Shishogi was not of a disposition to rule. The number of people Shishogi could trust had gradually diminished to none.

But now he couldn’t dismount the beast he’d guided for so long. He couldn’t emotionally accept the world as it was now. He couldn’t physically recreate the world he’d been born to. And if he let go, even if he resigned at this hour—the beast he’d created would turn on him and hunt him down for what he knew, and expose all he had ever done.

What did a man like that do—when the heavens proved so much larger than his world?

Where had all that cleverness deviated off any sensible track?

Shishogi had found a few individuals he could carefully move into position. And a few more. And a few more, all people who shared his views . . . or who were closely tied to those who did. Certain people found their way to power easy. Certain others—didn’t. Bit by bit, there was structure, there was a hierarchy, a chain of command that could get things done—things Shishogi approved.

This—this network—was the Shadow Guild.

Legitimate Assassins took years in training, spent long years of study of rules and law, years of weapons training, training in negotiation skills—and legitimate Guildsmen came out of that training with a sense of high honor about it all. The Guild didn’t just arm a three-month recruit and shove him out to shoot an honest town magistrate in the public street because somebody ordered him to.

The Shadow Guild had taken care enough in choosing its upper echelons. It had some very skilled, very intelligent people at the top. But all its recruits couldn’t be elite. And once the Guild tried to run the aishidi’tat, it lacked manpower. The handlers behind Murini, with a continent to rule, suddenly needed enough hands to carry out their orders. Legitimate Guild having retired and deserted the headquarters in droves, refusing to do the things the new Guild Council ordered—the Shadow Guild was suddenly in a bind. Controlling Guild Headquarters was one thing. Controlling the membership had proved something else altogether. Controlling the whole country had finally depended on misleading the membership.

And how had this shadowy splinter of the Guild proceeded, then—this old man, these officers, suddenly in charge of everything, building a structure of lies? A small group of their elite had a shared conservative philosophy. Its middle tiers weren’t so theoretical—or as skilled. Perhaps in their general recruitment, they’d given a little pass to those about to fail the next level, let certain people through one higher wicket, and then told them they were making mistakes and they would take certain orders or have their deficiency made known. That was one theory that Algini held. It had yet to be proved.

Early on, for the four decades before the coup, the nascent Shadow Guild had taken very small actions, carrying on a clever and quiet agenda, exacerbating regional quarrels, objecting to any approach to humans, constantly trying to gain political ground. The Assassins’ Guild, bodyguards to almost every person of note in the aishidi’tat, knew what went on behind closed doors.

But when a second human presence had arrived in the heavens, when Tabini had named the paidhi-aiji a lord of the aishidi’tat, claimed half the space station, and let the aiji-dowager take over operations in the heavens—that had not only scared the whole world, it had upset a long, slow agenda. Technological change had poured down from the heavens. There was suddenly a working agreement with the ship-humans. Atevi had become allies with the humans on Mospheira. And from very little change—change suddenly proliferated, while the world wondered what was happening up there and who really was in charge?

Tabini had fortified himself, anticipating opposition to his embracing human alliance: he’d set his key people into the space station, out of reach of assassination, and then sent the aiji-dowager, his heir, and the paidhi-aiji—as far as the world could conceptualize it—off the edge of the universe.

His allies had been upset.

His enemies had been alarmed.

The little old man in the Guild, seeing the world going aside from any future he had planned, had seen a need to strike now—and he’d done it, sure his people would be commanding the Assassins’ Guild and they’d gain immediate control, for a complete reversal of Tabini’s policy.

He’d been wrong. Not only had the middle-tier Assassins’ Guild officers turned obstructionist when Murini took power, the upper echelons had organized to fight back. Other indispensable guilds had taken heart and declined to cooperate: the Scholars, the Treasurers, even Transportation had balked.

Then Murini himself had proven hard to manage.

To take over the continent, to inflict the terror they’d instilled, and to do the deeds they’d done, the Shadow Guild had had to resort, ultimately, to the three-month recruit given a photo and an entirely illegal mission.

The day the coup had moved to assassinate Tabini—a fact they all had known from early last year—the Assassins’ Guild Council had been taken by surprise.

But Tabini himself hadn’t been caught so easily—whether by accident, or a feeling of unease or the action of his very skilled bodyguard. The Assassins who had attacked Tabini’s residence had gone in flawlessly, very high-level, as Algini put it, meaning people of extreme skill, with absolutely no leaks in their operation . . . and one could, Algini had said, almost guess which unit.

But with all that expertise, they’d missed Tabini.

Had Tabini’s bodyguard, on nothing more than a sudden bad feeling—taken him and his consort for a sudden vacation in his maternal clan territory of Taiben?

Certainly the rest of the legitimate Guild, hearing that a group in their guild’s uniform had invaded the aiji’s apartment and killed the aiji’s servants—among them, other senior Guild members—was not going to fold its hands and hope for better news in an hour.

The legitimate Guild, realizing the aiji was the target of an assassination, and that Tabini might have escaped, had immediately launched an emergency plan to protect key people and networks and secure the government against disorder. They’d been too late to prevent the second strike against Tabini, at Taiben, but records, people, and accesses had gone unexpectedly unavailable to the conspirators—the same way, Bren thought, that his own servant staff, carpets, and furniture had been loaded onto a train and reached Najida before Murini’s hangers-on could lay hands on them.

The conspirators had had far more important things than the paidhi’s household furnishings vanish in those initial hours—things like the shuttle manuals; the access codes for the state archives and records; the aiji’s official seal—any number of things that would have let them do more harm than they had done.

Once the legitimate Guild had begun to question the new administration’s orders, very senior Guild officers had begun to retire, an hour-by-hour cascade of retirements—which the conspirators had at first mistaken for the old guard’s acquiescence to a new administration. They had neglected to go after those officers and kill them. Or perhaps they’d tried—and lost a few teams.

These Guild officers, in those first few days, had needed to find out what had happened to Tabini—but they dared not risk their search leading the enemy straight to him, either. No, the legitimate Guild’s next move had been further afield, to establish contact with, of all people, the humans, the Mospheirans. That not-quite-high-tech linkup operation had required several men and a small boat loaded with explosives in case the navy, under the orders of the new aiji, should overhaul them.

Mospheiran authorities had been extremely glad to see them. Mospheira had stayed in close contact with the station, and the station included Geigi and the atevi community aboard the space station.

Individuals among the Missing and the Dead had linked up with Lord Geigi and set themselves at least nominally under his command.

Establishing contact with Tabini, even finding out whether he was alive—had posed a far more formidable problem. They had hesitated to invoke any network that might contact Tabini until they knew, first, that they could protect him and, secondly, that their own ranks were not infiltrated. But they had to take it on the thinnest of assurance that he was still alive.

When Tatiseigi opened his doors to Ilisidi on her return from space—Tabini knew about it almost within the hour. Tatiseigi’s security and their outdated communications equipment had leaked like a sieve in those days; but one of those leaks had gone in a very good direction . . . and kept Tabini minutely aware of what was going on in the world.

In just two years of rule, Murini had set himself and his supporters on the wrong side of public opinion. From one shore of the continent to the other, ordinary citizens had been organizing in small groups, considering what they could do on their own to get rid of Murini.

And when Tabini turned up alive, with the aiji-dowager and his son appearing at his side and reporting success in the heavens, he had met widespread public support. In that rising tide, the Shadow Guild had made one attempt on Tabini, the dowager, and Lord Tatiseigi—but they’d stopped that, with unfortunate damage to Lord Tatiseigi’s grounds—and a bedroom.

And when that attack failed, when it all began to fall apart, Murini and his closest staff had run for the Marid and Murini’s government had disintegrated.

In the one year since their return, Tabini and the aiji-dowager had been systematically turning over rocks left in that landscape, seeing what crept out from underneath—forgiving a few, putting some on notice, and doggedly going after the leaders. Murini had been among the first to go.

The rest had been harder. But the Shadow Guild had made truly interesting enemies in their two years in power. To firm up a deal with their allies in the northern Marid, they had made the mistake of targeting young Machigi, lord of the southern Marid, and run up against Machigi’s high-level but locally-trained bodyguard.

Now Machigi, seeing the way the wind was blowing, had signed a trade agreement with Ilisidi—the first step toward an agreement with the aishidi’tat, granted only that Machigi kept his fingers off the west coast.

The Marid clan from whose territory the Shadow Guild had targeted Machigi—the Dojisigi—had now fallen to the legitimate Guild, who had lately taken the Dojisigi capital and forced the Shadow Guild out.

But not entirely. In the last month, the Shadow Guild still hiding in that mountainous province had tried an entirely new maneuver. By an order ostensibly from the legitimate Guild—they were still asking who had issued that order—they had first disarmed the best of the native Guild units, then sent them out to defend the rural areas—without returning their equipment.

That matter had only turned up last night, when the dowager had taken up two of the Dojisigi Guild who’d been thus mistreated—and made a move to rescue several hundred innocent countryfolk. Her units in the south had just last night laid hands on two of the Shadow Guild’s surviving southern leadership—and what she learned had given the dowager the legal cause she needed to go against the Kadagidi in the north, this morning.

Now the Kadagidi lord, Aseida, was up ahead of them on this train, being grilled nonstop by the dowager’s bodyguard—men themselves extremely short of sleep, and who had just been shot at by Shadow Guild operatives that Lord Aseida had been harboring.

Lord Aseida, who himself was no great intellect, had claimed innocence of everything. Aseida’s chief bodyguard—Haikuti—had been the Shadow Guild’s chief tactician, the man who for two years had ruled the aishidi’tat from the curtains behind Murini. Haikuti might have conducted the attacks on Tabini’s residence.

The Tactician had not made many mistakes in his career. But the ones he had made had finally come home, on a red and black bus from Najida Province.

First—Haikuti having himself the disposition of an aiji, a charismatic leader whose nature would accept no authority above him—he would have done far better to set himself in Murini’s place. There had been a point . . . with the panicked legislature agreeing to whatever Murini laid in front of them . . . when Haikuti, despite his unlordly origins, could easily have done away with Murini and seized power in his own name—except for one very important fact: Haikuti belonged to the Assassins’ Guild; and anyone once a member of that guild was forbidden to hold any political office. Ever.

Haikuti, had he held the aijinate, would not have frittered away his power in acts of petty-minded vengeance. But, personally barred from rule, Haikuti hadn’t seen fine control over Murini as his own chief problem. He was busy with other things.

Second, he was by nature a tactician, not a strategist, which meant he should never make policy decisions . . . like letting Murini issue orders.

Unfortunately, the Shadow Guild’s Strategist had not always been on site to observe Murini in action—and Murini’s actions on the first full day of his rule had alienated the people beyond any easy fix. It had also rung alarm bells with the legitimate Assassins’ Guild and sent them to Mospheiran sources for better information.

From that day, the tone and character of Murini’s administration was set and foredoomed, and while the Shadow Guild had begun to treat Murini as replaceable, and to ignore him in their decisions . . . the Shadow Guild had chosen to use the fear Murini’s actions had created and just let it run for a year or so, while they launched technical, legal maneuvers through the legislature. The Strategist had taken the long view. The Tactician just let Murini run, to stir up enemies he could then target.

Unfortunately—the second mistake—neither had understood orbital mechanics, resources in orbit—or Lord Geigi’s ability to launch satellites and soft-land equipment. They had thought grounding three of the shuttles would shut off the station’s supply, starve them out, and that Geigi’s having one shuttle aloft and in his possession was a very minor threat.

Third and final mistake, Haikuti had had a chance to run for it this morning when he had realized it was Banichi who was challenging him. But his own nature had led him. Haikuti had shot first. Banichi had shot true.

That had been the end of Haikuti.

The Strategist, Shishogi, Haikuti’s psychological opposite—was a chess player who made his moves weeks, months, years apart, a man who never wanted to have his work known and who was as far as one could be from the disposition of an aiji. He had no combat skills such as Haikuti had—to take out a single target in the heart of an opposing security force.

Deal in wires, poisons, or a single accurate shot? No. The Strategist had killed with paper and ink. He was still doing it.

Papers that sent a man where he could be the right man—a decade later.

Papers that, in the instance of the Dojisigi, could undermine a province and kill units in the field.

For forty-two years, in the Office of Assignments in the Assassins’ Guild, Shishogi had recommended units for short-term assignments, like the hire of a unit assigned to carry out a Filing by a private citizen, or the unit to take the defensive side of a given dispute. He had recommended long-term assignments, say, that of an Assassin to enter a unit that had lost a member, or the assignment of a high-level unit to guard a particular lord, or a house, or an institution like the Bujavid, which contained the legislature.