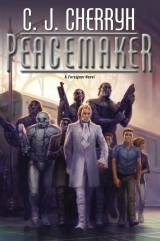

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

To you and to your great-grandson I leave my estate at Najida, and I also put Najida Peninsula and its people in your care.

To Geigi:

I have undertaken a mission against enemies of the aiji. Please take care of those closest to me, guard those I would guard, and remember me as someone who wished atevi and humans to live in peace. I have every confidence you will find a path between the ship-aijiin and the Mospheirans, between humans and atevi, and from the old ways into the new. I have complete confidence in your management of affairs in the heavens. I believe you will bring about a good solution, and I only regret that I must leave you with so much yet to do.

To Tatiseigi:

I am honored by the generous hospitality you have shown me over many years. I am particularly honored by your acts of trust and support for me personally despite our differences of degree and birth. With every year I have understood more and more why the aiji-dowager favors you so highly, and I have every confidence in her recommendations. I have asked her to care for my staff, and hope that you may assist her with that matter, as I hope you will look favorably on my people. Go with her and keep her safe. Trust Jase-aiji. He will not understand every custom, but he will do everything for your protection.

To Narani himself:

Accept my deep gratitude for your extraordinary service, your courage, and your inventiveness. I have asked the aiji-dowager to make provision for you and for senior staff, and I have bequeathed Najida to her and to her great-grandson, where you also may have a place should you wish it. I ask you see to the disposition of my clerical staff, and to the execution of my more detailed will, which you will find in the back center of my desk, under my seal. No one could have a more faithful manager than you have been, here and on the station.

It was a somewhat depressing set of notes to have to write, but curiously—it left him feeling he wanted his favorite dessert as lunch today, just in case; and he felt an amazing lack of stress about the idea of not having breakfast the next morning. He usually conducted his affairs in a tangled mess of this obligation and that, with overlapping scheduling, priorities jostling each other and changing by the hour—and he usually managed most of them.

But—regarding tomorrow—he discovered not one thing that he really had to do. The peripheral objectives were, for once in his career, all bundled up and handled fairly neatly.

Oh, he had things he wanted to do, or should do—he always had; but there was absolutely nothing weighing on his shoulders as impending catastrophe if he didn’t. The people he’d written the notes to would handle everything as well as it could be handled.

Protection? Safety? He was going to be with the people who made him feel safe, come what might.

It was, contrarily, their guild he was trying to rescue, and for once he could help them.

They were, meanwhile, setting things up with all the skill and professional ability anyone could ask.

He was certainly not going into the situation planning his own demise—but there was satisfaction in the plan. Any strike at him would give Tabini and their allies plenty of moral righteousness, and the absolute right to send heads rolling, politically speaking—or literally. The assassination of his messenger to the Assassins’ Guild would also justify Tabini taking to the skies and settling matters from orbit.

Disband two clans of the aishidi’tat, the Kadagidi and the Ajuri? That could certainly be the outcome, given the documentation and the witnesses the aiji-dowager now had in hand.

And in a time of major upheaval and a threat to the Guild system itself—and with Ilisidi stirring up her own factions to vengeance—Tabini might just take out two clans that had been a perpetual thorn in his side, at the same time he brought in the two tribal peoples.

The paidhi-aiji’s demise under such circumstances would, politically, unify several factions, not that he was the favorite of several of them—but that the whole concept of the Assassins’ Guild, enforcers of the law and keepers of the peace, violating its own rules to strike at a court official with the aiji’s document in hand would not sit at all well with the Conservatives, the very people who were usually most opposed to the paidhi-aiji’s programs. His enemies among the Conservatives were not wicked, unprincipled people—they just happened to be absolutely wrong about certain things. They would far rather support the rights of a dead paidhi than the live one who had so often upset the world.

And the prospect of the arch-conservatives avenging him . . . afforded him a very strange amusement.

He was, perhaps, a little light-headed after that spate of pre-posthumous letter-writing, but he honestly could not readily recall a time when there was so little remaining on the docket that the paidhi-aiji could reasonably be responsible for.

So. He did not deal with tactics. That was his aishid’s business.

It was not his worry what Ilisidi was doing about the Shadow Guild in the south or Lord Aseida’s future in the north.

He had no more now to do with entertaining Cajeiri’s young guests; and he certainly didn’t want to hint to the boy that there was anything so serious going on.

The one thing he did need to do right now, and urgently, was to get a meaningful document with Tabini’s seal on it . . . on some issue that would not be what the current Guild leadership feared it was.

He encased the collection of letters in one bundle, with Narani’s letter outermost, encased in a paper saying, To open only in event of my demise. Thank you, Rani-ji.

He tied it tightly with white ribbon. He sealed the knot with white wax, and imprinted it with the paidhi-aiji’s seal.

Then he wrote one additional letter, to Tabini:

One asks, aiji-ma, that you prepare a document with conspicuous seals, empowering the paidhi-aiji, as your proxy, to bring a complaint before the Assassins’ Guild Council this evening.

One asks, aiji-ma, that you complain not of the situation in the north, but that you bring to the Guild’s attention the situation in the Taisigin Marid, wherein units from the capital were dismissed into the country without their weapons or equipment and where the aiji-dowager has had to intervene to restore order. One asks that you strongly question that decision and do not mention the other.

One asks further, that I be sent under your order, to deliver this document, and file it with the Guild.

He didn’t seal it. He gave the first bundle to Narani, personally, saying, “Rani-ji, these letters should not be delivered unless it is likely that I am dead.”

“Nandi.” Narani bowed, with a rare expression of dismay.

“Which one does not intend should happen,” Bren added hastily, “and if it does not happen, I shall certainly, and in great embarrassment, ask for this bundle of letters back again and destroy them. But what must be delivered quickly and certainly is this letter.” He handed Narani the second letter, as yet unrolled. “Please take this letter first to my aishid and ask if this will serve their needs. Then, granted their approval of it, place the letter in my best cylinder and personally deliver it to the hands of the aiji, no other, not his major domo, not the head of his guard, and not the aiji-consort. To him alone. Await a response.”

“Nandi.” A deep bow, and the old man took both the bundle of letters and the letter to Tabini.

“Tell my aishid, too, I have ordered a light lunch, and a dessert,” he added. “With enough for them, whether at table, or in their quarters. They may modify that request at their need. And tell my valets I shall need court dress this evening, with the bulletproof vest.”

“Nandi,” Narani said a second time, bowed, and left with the letters and his instructions.

10

Narani did not come back. Jago did. She opened the office door quietly and closed it.

“We certainly approved the letter, Bren-ji,” she said. “And Narani is delivering it to the aiji.” There was, unusual for Jago, a distressed pause, as if she wanted to ask something, but refrained.

“Are you wondering whether I really understand what may happen? Yes, Jago-ji. I do entirely understand. That is why I am going.”

“It is still difficult,” Jago said quietly, “for us deliberately to bring you into extreme danger, Bren-ji. It is very difficult.”

“One appreciates your sentiment,” Bren said. “And I will take instruction, Jago-ji. I only ask that you value yourselves highly as well.”

“Yes,” she said shortly, not happily. Then: “Cenedi must get out alive. Banichi and Algini must get out alive. You—we shall try, Tano and I.”

“Jago-ji.” He began to protest the priorities, and then kept quiet—just gave a nod of acceptance. “As you decide, Jago-ji.” He was far from happy about any of them putting his life on a higher priority than their own, and took a deep breath, steadying down and refraining from any discussion of what was likely a recent decision. “I am following orders, in this matter.”

“We hope certain units, in certain areas, will not resist us—once they understand. That will be your job, Bren-ji. We cannot advise them of our intentions in advance. If we bring in one unit on the plan—we cannot absolutely rely on their discretion with their closest ally. If we bring in another—we do not want it said that their lord’s personal grudge was behind the action we take. If we bring in a third, others will ask why they then were left ignorant, or what motivated the choice of those so honored. Politics, Bren-ji. But I do not have to explain that to you.”

“No. No, that much I understand.”

“If we can get out of this without firing a shot, excellent. And we rely on you—not to be stopped. If we can do that, it will be, baji-naji, a surgical operation—at least as far as the second door. That one—we shall finesse.”

Baji-naji covered a lot of ground: personal luck and random chance. Their own importance in the cosmos and the flex and flux in the universe. If people couldn’t die, the universe couldn’t move. The baji-naji part in the operation—seemed to be his. And it was a big one.

Finessing the situation, in Guild parlance—meant anything it had to, with minimal force—to move what they could, any way they could, in this case, amid all the tiny threads of connection, kinship, man’chi, and regional politics that wove the Guild together, moving in to take down the Guild leadership—and clip one little frayed Ajuri thread, without disturbing what held the Guild together. Atevi politics wasn’t human politics. The dividing line between personal interests, man’chi, and clan interests was not always apparent—even to the people in the middle of the situation, whose emotions might be profoundly affected by what they had to do.

And if he understood what Jago was saying, they were relying on his presence to jostle nerves, create hesitation . . . because everybody on the planet knew the aiji’s representative was the only human on the continent . . . and pose their potential opponents a problem.

Posing a problem. He’d done that in the legislature, now and again.

Only the legislators, however agitated they might become, weren’t armed.

“I’ll—”—do my best, he had begun to say, but a rap on the door announced Narani, who bowed and said quietly, “The dowager, nandi, is sending a message.”

Ilisidi had heard they had cut her out of the operation. And Ilisidi sent a message that she was sending a message?

Damn.

How had she heard? He trusted his staff. He knew who they reported to. Him.

He’d only sent to—

Of course—Tabini’s staff. Tabini’s borrowed staff. Damiri’s.

He needed to get that document from Tabini before he faced the dowager with his explanation of what he’d done.

“Excuse me, Jago-ji.” He stood up, went out into the hall and to the foyer with Jago right behind him. “My second-best coat,” he said to Narani, who kept the door. With luck he might get out the door and headed for Tabini’s apartment before a message arrived to complicate matters.

His major domo got the coat himself, and helped him on with it. He attended them, opened the front door.

No escape. The dowager’s man Casimi was headed down the carpeted center of the hall toward them, and there were only two apartments at this bag end of the hall—no doubt on earth what the dowager’s man intended, and they could hardly claim ignorance of the fact he was coming.

He hoped the oncoming message didn’t include Ilisidi’s order to abandon the idea or come immediately to explain the situation. He wasn’t going to get shut out of the plan, and he didn’t want a debate—not to mention defying Ilisidi to go over her head as he was about to do. That was not going to please the dowager.

There was no escape, however. He was obliged to wait the few seconds it took Casimi to reach their door. With a backward step and a nod, he signaled Narani both to let Casimi in and to close the door on their generally empty corridor—for whatever privacy they could fold about a likely argument.

“Nandi,” Casimi said, trying not to breathe quickly, “the dowager has heard you intend to go with your aishid to the Guild tonight.”

“She has heard correctly, nadi,” Bren said.

“She wishes you to decide otherwise.”

No request to speak to him personally, nothing of the sort, indeed, simply an order he did not intend to honor. He opened his mouth to refuse.

But Jago said, at his side, “Cenedi is on his way here, nandi.”

Cenedi. The dowager’s head of security.

Was Casimi not enough?

Casimi himself looked perplexed, hearing that, and quietly stepped to the side and ducked his head, withdrawing from the question, as well he should, with his senior officer about to enter the matter.

A short knock came at the door far sooner than the typical walk from the dowager’s door would require. Narani looked at Bren for instruction, Bren nodded, and Narani quietly opened the door.

Cenedi arrived alone, not breathing hard, and from the left, where there was only one apartment.

“Tabini-aiji is coming to call, nandi,” Cenedi said, with a little nod of courtesy.

Rank topped rank.

“Indeed,” he said with an outflow of breath. Was it the Kadagidi situation that brought Tabini here instead of calling him there, one could wonder—or was it the Assassins’ Guild situation and the dowager’s proposal to go lay siege in person?

Narani was standing by the door, ready for orders. All it took was a glance and a nod and Narani passed the matter of the door to Jago, then headed for the adjacent hall to advise staff to prepare the sitting room for a visitor.

Bren said to Casimi, with a polite nod, “One is under constraint, nadi. One by no means intends discourtesy to the dowager. Please offer my respects and say that I am required to receive the aiji’s intention, whatever that may be.”

“Nandi.” Casimi bowed in turn and left. So there they stood, himself, Cenedi, and Jago, with Tabini inbound and their plans—

God only knew who sided with whom or what Tabini wanted in coming here. Tabini had had time to read the letter Narani had taken to his office.

So one waited for the answer.

Came quick footsteps, advancing from the inner hall of the apartment: Jeladi arrived with a little bow and took Narani’s place as doorkeeper. “My apologies, nandi. Staff is heating water and arranging the sitting room for the aiji.”

A committee in the foyer was no way to receive the lord of most of the world into his apartment . . . not after sending a letter that might have prompted the unprecedented visit. Bren said, quietly, “Jago-ji, advise the others,” before he headed for the sitting room himself. There he settled in his own usual chair, and had the servants add chairs for the bodyguards, who would very likely be involved. Or who might be. He had no clue.

· · ·

“You must come to the sitting room,” Madam Saidin said, at the door of the guest quarters. “Your great-uncle has asked Master Kusha. You must come and be measured.”

Clothes. He hated being measured. “Master Neithi already has my measurements.”

Master Neithi was his mother’s tailor. And he had been measured for court clothes just before he had gone out to Najida.

“Yet your great-uncle wishes to make you a gift, young gentleman, and we have no wish to involve Master Kusha in a rivalry with Master Neithi.”

A rivalry. He caught that well enough. Jealousy between the tailors. The whole world was divided up in sides. At least tailors did not shoot at one another. But anyone could be dangerous.

“One does not wish Master Neithi to be upset, Saidin-daja.”

A little bow. “That will absolutely be considered, young gentleman. This is only in consideration of your wardrobe stalled in transit, and,” she added quietly, “most of all for the comfort of your guests, young gentleman, since your great-uncle feels they may be a little . . . behind the fashion. And perhaps under supplied.”

If he was getting clothes, they had to get them, too, without ever saying what they had come with was too little, besides the fact that they had had to leave almost everything they owned at Great-uncle’s estate. “Thank you,” he said. “Yes, Saidin-daja. One understands.”

“Excellent. Please bring your guests to the sitting room. There will be clothes for them.”

That was a cheerful note—among so many things in his situation that were not. They had gotten up, had breakfast, just himself and his bodyguard and his guests—and they could go nowhere and they had done everything. It was getting harder and harder to turn his guests’ questions to safe things. They had talked about all the pictures in the tapestries. They had inspected all the vases in the rooms they were allowed to visit. They had played cards, and he had tried not to win and not to be caught not winning.

He was glad to bring them something they would enjoy.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said, “Madam says there is a surprise.”

They sat around the table, with the cards neatly stacked and the game in suspension—they were trying very hard not to be bored, or worse, worried. Boji of course had set up a fuss, bounding about in his cage and chittering, sure that someone coming meant food. Boji had been in the bedroom, but since they were sitting out here in the little sitting room, of course they had had to roll Boji’s cage in here so Boji could see everything. Boji sat on his perch now with an egg in his hands—a bribe he got whenever he started to pitch a fit—staring at him with eyes as round as his guests’ solemn stares . . .

But his guests’ faces brightened when he said a surprise—not in the least suspecting, he thought, what that might be. They all pushed their chairs back and got up without a single question.

That was his guests on especially good behavior, with people going and coming and doors opening and closing all morning, and with not even his bodyguard permitted to go out the main doors. They knew something was going on. But a surprise? They were in completely in favor of it.

So was he.

“Eisi-ji, Liedi-ji,” he said to his valets, who were trying to keep Boji quiet, “do come. Taro-ji.” His bodyguards were sitting at their own table, with books open, studying things about trajectory. “We shall just be in the sitting room.”

So out they went, himself, his guests, his two valets, out and down the hall to the sitting room, falling in behind Madam Saidin.

The sitting room door was open. A tall, thin man, the tailor, by his moderately more elegant dress, presided over a changed sitting room—with sample books, piles of folded clothes on several chairs; and two assistants, one male, one female, with notebooks and other such things as tailors used. There was even a sewing machine set up on its own little stand, which usually came only at a final fitting.

“Master Kusha, young gentleman,” Madam Saidin said, and there were bows and courtesies—no tea. One never asked a tailor or a tutor to take tea.

“Nadi,” Cajeiri said, with a proper nod. “One is grateful. Thank you.”

“Honored, young gentleman, and very pleased to serve—one understands these excellent young guests and yourself have arrived without baggage, some misfortune in transport? But the major domo at the lord’s estate has relayed the numbers, and we have brought a selection of the highest quality, which we can readily adjust for general wardrobe; and we shall, of course with your permission, take our own measurements for court dress. One never has too extensive a wardrobe, and we are honored to provide for yourself, and your guests.”

Master Kusha had a long and somewhat sorrowful face, and he was not young. Rather like many of Great-uncle’s staff, he was an old man, but likely, too, he was a very good tailor.

“We shall ask your guests to try on these for fit. We shall make just a few little changes—understand, nandi, simplicity, simplicity of design that needs the slightest touch of sophisticated alteration, a tuck here, a little velvet, and lace: floods of lace can make all the difference. One will be amazed, nandi, one will be amazed at the transformation we can work in these on short notice. Let us show what we can do.” He waved his hand, and the assistants swept up the stacks on the chairs, ready-made clothes, coats and shirts apt for Gene, who was broad-shouldered and strong and tall, and for Artur, whose arms were almost Irene’s size around; and clothes for Irene, who was tiny and the oldest at once.

“Put these on, young gentlemen and lady,” Master Kusha said, “and then we shall do alterations, and I shall get my numbers for court dress, the very finest for all—will they understand at all, nandi?”

“Put them on, nadiin-ji,” Cajeiri said, with a little wave of his hand. “Try. This all is yours.”

They were not happy at that. Not at all. He saw it.

“Something wrong?” he asked in ship-speak.

“Talk,” Gene said, setting down his stack of clothes. “A moment. Talk. Please.”

He was puzzled. Distressed. He gave a nod to Master Kusha, another to Madam Saidin. “A moment, nadiin,” he said. “Translation. One needs to translate for them.”

“Young gentleman,” Madam Saidin said, and quietly signed to Master Kusha to step back.

So they were left as alone as they could arrange. And something was direly wrong.

He should, he thought, call for tea. If he were his father.

Or if they were atevi.

But neither thing was true. So he just drew them over to the farthest side of the room, and turned his back to Madam Saidin and Master Kusha and all of it, trying to muster up his ship-speak, which had gotten a little thinner than it had once been . . . that, or human words were not as suited to things on the Earth, and were just not as clear to him as they had been.

· · ·

It always took a while for the lord of most of the world to do anything simple, what with staff to advise of his movements and arrangements to make. If Cenedi had blazed over here, leaving a conference with Tabini, it might have been Cenedi’s briefing Tabini on the Padi Valley business yesterday that had prompted the personal visit—but given the dowager’s notions of invading the Guild herself, it was much more likely this evening’s business under discussion.

This evening’s business—and maybe the document he had requested.

One did guess that if Tabini was coming here to discuss whatever matter Tabini wished to discuss, Tabini had certain specifics he didn’t want to discuss in his own quarters—quarters which he shared with his wife, Cajeiri’s mother, whose clan, Ajuri, was deeply at issue in the Padi Valley action—not to mention directly involved in their upcoming business with the Assassins’ Guild.

God, he hoped Tabini had found no reason to doubt the aiji-consort at this point. Tabini had maintained his association with Damiri when common sense might have dictated he divorce his wife as a political and security-based precaution—an action which, with Damiri no more than a week from giving birth, had its own problems. Tabini couldn’t divorce Damiri at this point. He surely wouldn’t set up a conflict with her.

Tabini had thrown out all Damiri’s staff a number of days ago, so that now all the senior security in Tabini’s apartment were the dowager’s people . . . hence the dowager’s very good grasp of what was going on in the world.

Discuss the imminent assassination of a Guild officer who happened to be Damiri’s relative?

He’d personally rather not have that discussion in Damiri’s hearing, either.

And probably that was exactly Tabini’s reasoning in coming here to talk. He hoped that was all that was going on . . . but there were ungodly many possibilities in the political landscape.

Tano and Algini arrived in the sitting room, with Banichi and Jago following. Banichi was not moving briskly today, and Banichi would not keep the arm rigidly bandaged. The hand stayed tucked inside the jacket. Bren just acknowledged Banichi with a particular nod—not arguing with him, not with life and death matters afoot.

There were, thankfully almost immediately, the quiet set of sounds that heralded an arrival at the front door. Not one man, but maybe two or three, Bren thought, by what he heard. So Tabini had not brought his full security detail with him, maybe not even his own aishid—unprecedented as the visit itself, if that was the case.

Servants hurried about last-moment preparations. Narani opened the door, showing Tabini into the sitting room with Cenedi, and with Cenedi’s frequent partner Nawari in attendance, not on the aiji-dowager, but on Tabini. Again—that had never happened.

Protocol dictated the paidhi rise, bow, offer a seat.

“Aiji-ma. One is honored.”

“Sit,” Tabini said, with an all-inclusive sweep of his hand—Bren, Cenedi, Nawari, Bren’s own bodyguard, everybody but the servants. It was an order, and Tabini was deadly serious.

“Tea,” Tabini said. Nothing of business was appropriate until they had had a cup, ritually delivered; and moods like Tabini’s current one were precisely the reason for the custom.

· · ·

“Nadiin-ji?” Cajeiri said, and made it a question. His guests looked very uncomfortable.

“I told you,” Irene whispered to Gene and Artur. “We just have to do things. Don’t make a problem.”

Gene and Artur did not even look at her. Or at him. Gene just drew a heavy breath.

“What?” Cajeiri asked. “What?”

But Gene and Artur said nothing, and still looked at the floor.

They were upset. That was clear. And it seemed to be about the clothes. “Children’s clothes look bad?” he asked. It was all that would fit them. “Master Kusha makes them right.”

“That’s not it,” Gene said.

“What?” he repeated, and then thought they might not understand the situation he could only explain in Ragi. “Nadiin-ji, our baggage may come tonight. Maybe not. And those are all country clothes. This is the Bujavid, nadiin-ji. You need better. You were always going to need better.”

“Whose credits?” Gene asked.

Whose credits?

Then he understood. For an instant he saw the ship corridors again, where humans had to have a card to get a sandwich or a drink, where everything in all their lives had been measured so closely, and you were allowed so much and more could not be had, because you had to work on the ship to earn a larger share.

None of the station-folk had been able to work, and all the share they had had even for food was what the ship allotted for them, measured out by how old you were and whether you were a boy or a girl and how tall you were—all of it calculated by a set of numbers atevi never had to calculate. If they were hungry on a particular day, they still could not get more. The station-folk had been really unhappy on the ship, which had been worse than the station. And sometimes people had been hungry.

Not his associates. Never his associates. He had brought them sweets from mani’s kitchen. Sausages. And bread.

He remembered. For an instant they were there in the tunnels again. “This is not the ship,” he said to his guests, and made a wide gesture at everything, the sitting room, the whole world, if he could have thought of the ship-speak words. “My uncle. My guests. No numbers here. You need the clothes.”

“What can we say?” Gene said. “It’s your birthday, Jeri-ji. We brought you presents. But nothing like this.”

“Presents.” Reunioners had come onto the ship with almost nothing, and it was painful to think how little they still must have, starting with nothing on a station where very few could earn extra.

But if they were his people, they had every right to match him, well, as far as lords could—because they were his. It was a matter of pride, and the way everybody would look at them. They could not wear their clothing: the old people would be scandalized—but he could not quite tell them they would embarrass him.

If he were a grown-up, he would be sure they could match him in exactly the right degree. But he was just eight. And it was very good of Great-uncle and mani to step in to fix things. It was only right that they did, because he was theirs, and it was their pride involved if his people looked wrong or rude.

But clearly it was not right, in his guests’ opinion. And one part of him hurt, as if they were pushing his gift rudely away, as if they were not wanting to be here today, and were upset and embarrassed.

But he was sure they really did want to be here. They were modest, and grateful, and always polite to him. That would not have changed in a handful of minutes. So he was the one at fault: he had to explain it in a way that would not embarrass them.

He shrugged, gave a second little shrug, and resorted to one of those stupid things they had used to say on the ship, when they were completely out of answers. “Atevi stuff. Atevi stuff.”

“Human stuff,” Gene said, the right answer and gave an answering and unhappy little shrug.

“Here!” he said, pointing at the floor underfoot. “You are here!” He wanted to say so much else to them, so very much else . . . but if there had been words they could understand to make it all work, he would not be atevi and they would not be human. And they just stood there, both unhappy, which was unbearable.

“Gene,” Irene said, trying to calm things down. “Just listen to him.”