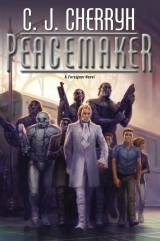

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“How long has this been going on?” Banichi asked, and after a deep series of breaths, Damiri said,

“Since yesterday.”

“Since yesterday.”

“I would not spoil my son’s festivity.” Deep breath, and in a tone of distress. “With him, I had two days.”

“It can be sooner.”

“I think, nadi, it could be before I get to the doors.”

Halfway to her apartment. “We are approaching,” Bren heard Algini say. And his ears told him, too, that someone was coming behind them, likely Madam Saidin. “The hall is secure. You are clear to unlock the doors.”

The doors ahead did open, wide, and the major domo and Damiri’s personal maid came hurrying out in great distress, ran to them and paced along beside as, behind them, indeed, Madam Saidin came hurrying into their company.

“One can assist her, nandi,” Madam Saidin said, easing herself into Bren’s place, while Damiri’s maid took her arm on Banichi’s side.

“I am no great assistance in this,” Jago said, “but I can at least provide communications.”

“Go,” Bren said. “Stay with her as long as need be.”

Tano arrived at a near run, from behind them. “Nand’ Siegi says he has not done this in thirty years, but he is coming, Bren-ji.”

“Well done,” he said. He thought perhaps he should go back to his apartment and wait there for news, but he was one person who could give orders if something had to be decided, and someone who could at least answer questions and explain to Tabini, when he got here—if protocol would let him get here—and he was determined to stay. He followed, stopped in the foyer with the major domo as Madam Saidin and Damiri’s maid assisted Damiri down the inner hall, toward her own suite, with Damiri’s two bodyguards and Jago following. Servants were hurrying about, everyone hushed and trying not to make a commotion.

Bren just stood there, with his aishid—with Banichi, who by the sound of his questions knew more than the rest of them put together regarding Damiri’s situation.

“One had no idea what to do,” he said to his aishid, a little out of breath.

“One cannot say Jago has,” Banichi said. “But she will tell us what she can learn, and the dowager’s men will not go past the sitting room.”

“Do you need to rest?” he asked. “Nichi-ji, do not hesitate.”

“One has no desire to add to the commotion,” Banichi said. There was a small bench built into the foyer wall by the major domo’s office, not an uncommon arrangement, and he quietly took it. “You might sit, Bren-ji.”

“I am too worried to sit,” he said, but he did sit down, for fear Banichi would get up again. “I precipitated this. I was too harsh with my answers. I was far too blunt. I upset her.”

“You gave her answers, Bren-ji. They were not pleasant answers, but they were answers. And she seemed to have wanted them.”

“Still . . .” he said, and saw by the sudden doorward look of everyone in the foyer that someone was coming. Human ears picked up nothing yet; but Algini took it on himself to open the door, hand on his pistol as he did so.

“Nand’ Siegi,” he said, and held the door open until the old man arrived, with an assistant carrying two cases of, one supposed, medical equipment and supplies.

“Where?” the old man asked, out of breath, and Tano showed him and his assistant down the inner hall and into the direction of the major domo, before Algini even began to shut the outer door.

But Algini stopped, and held the door open. “The aiji is coming,” he said.

Banichi used the bench edge to put himself back on his feet. Bren stood up, and the major domo arrived back in the foyer, from down the hall, agitated and worried. Algini ceded him the control of the door as numerous footsteps approached.

Tabini arrived, with Cajeiri, with his double bodyguard, and Cajeiri’s, too many people even to get into the foyer conveniently.

“How is she?” Tabini asked at once.

The major domo said: “Well, aiji-ma. She seems well. Nand’ Siegi is here.”

“Paidhi!” Tabini said, shedding his coat into the major domo’s hands, and there was no assistant to provide another. “Take care of my son.”

“Aiji-ma,” Bren said, and Tabini, in his shirt sleeves, and with only his junior bodyguard, headed down the long inner hall, toward his wife’s suite.

Cajeiri cast a worried look after him, then looked Bren’s direction. Worried. Scared, likely, and trying not to show it.

“Your mother walked to the apartment,” Bren said, “and she seems well enough. Nand’ Siegi just arrived.”

Nobody had taken the boy’s coat. The major domo had gone back down the hall in a hurry, following Tabini. Guild was talking to Guild, meanwhile, exchanging information partly verbally, partly in handsigns, and there was a general relaxation.

“I think we could do with a cup of tea,” Bren said quietly. “Can we arrange that?”

“Yes,” the Guild senior of Tabini’s guard said, and headed down the same hall, while Bren steered Cajeiri, Cajeiri’s bodyguard, and his own three toward the sitting room, the civilized place to wait.

“Sit,” he said to them, in consideration of Banichi. “Everybody sit. We are not in an emergency now.”

“Is she really all right, nandi?” Cajeiri asked.

“She seemed quite in command,” Bren said. “Madam Saidin is there; Jago is, and now nand’ Siegi.” There was another small commotion in the foyer, even as he spoke. “That may be her own physician—he had to come up from the hotel district.”

“Jago reports your father is with her, young aiji,” Tano said, “and she knows you are here.”

“My father says I should not go back there,” Cajeiri said unhappily.

“There are so many people,” Bren said. Two of the kitchen help were making their tea, over at the side of the room: there was not a senior servant nor a woman to be seen, when ordinarily a handful would have flitted through, checking on things, being sure the fire was lit, the chairs were set. “I think that is your mother’s physician who just arrived.” He could see an older woman and a younger pass the door. “Everyone who needs to be here is here.”

“My father sent word to nand’ Jase,” Cajeiri said, “and he is going up to Great-uncle’s apartment. I think my great-grandmother has taken charge of the party.”

“That was well-thought,” Bren said.

“But Kaplan and Polano . . .” Cajeiri said. “How do they get upstairs?”

That was a question. The poor lads were down there for security. “One believes Jase will give them orders; and they were prepared to be there until the party ended. They will be there for your great-grandmother, and, one supposes, Lord Tatiseigi’s safety, as well. And your guests will be upstairs, able to get out of these fancy clothes, so one supposes they are more comfortable than we are.”

“Is she going to be all right, nandi?”

“There is nothing that indicated anything to the contrary, young gentleman. She simply knew it was time, and she had us all escort her upstairs. Apparently,” he added, because the boy and his mother were too often at odds, “she has been having pains since yesterday, but she wanted you to have your festivity without the disruption of her taking to her bed. She thought she could get through the evening.”

“She did?”

“She is quite brave, your mother is, and she knew it was a very important evening.”

Cajeiri just stared at him a moment. “I wish she had said something.”

“But your father would have worried. And you would have worried.”

“She is going to be all right?”

“Baji-naji, young gentleman, but your mother is too determined a woman to do other than very well.”

“I am glad you call me young gentleman. I am not ready to be young aiji.”

“You had no idea your father would do that?”

“None at all, nandi!”

The boys were standing by, awaiting a nod before setting the cups down. Bren gave it, and took the teacup gladly enough.

Cajeiri put sugar into his. And drank it half down at one try.

“Did you ever get to eat?” Bren asked him.

“No, but—” Cajeiri began, when there was a sudden noise of footsteps from down the hall, and the major domo came hurrying in, to bow deeply in Cajeiri’s direction.

“Young gentleman, your father sends for you.”

Cajeiri set the cup aside, looking scared.

“Is it good news?” Bren asked sharply, startling the man, who bowed again.

“The aiji-consort is very well, nandi. The young gentleman has a—”

Cajeiri bounced to his feet and headed out the door at a run, taking a sharp right at the door, his young aishid rising in complete confusion.

“—sister,” the major domo finished, and bowed in consternation. “Please excuse me, nand’ paidhi!”

The major domo hurried after. Cajeiri’s bodyguard stood by their chairs, confused.

“As well sit and wait, nadiin,” Banichi said, as Tano and Algini looked amused. “There is no use for us back there.”

Bren let out a slow breath, and took a sip of tea, affording himself a little smile as Cajeiri’s young bodyguard settled back into their chairs, deciding there probably was no further use for their presence, either.

But they might as well finish the tea.

· · ·

Mother was propped with pillows, and her hair was done up with a ribbon. Father was in a chair at her bedside. And there was a white blanket in Mother’s arms, just the way it was in the machimi. It all seemed like a play, like it was somebody else’s family, somebody else’s mother and father, on stage.

But he came closer, and Mother smiled at him, and moved the blanket and showed him a little screwed-up face that hadn’t been in the world before.

“This is Seimiro,” Mother said. “This is your sister.”

He looked at his father, who looked at him; he looked at his mother. He looked at the screwed-up little face. He had never seen a really young baby.

“Is she asleep?” he whispered.

“She hears you,” his father said. “But she cannot see you yet.”

“Can I touch her?”

“Yes,” his mother said.

He put out his hand, touched her tiny fist with just one finger. She was unexpectedly soft, and warm. “Hello, Seimiro,” he said. “Hello. This is your brother.”

“Do you want to hold her?” his father asked.

She was so tiny. He knew he could. But she was so delicate. And his mother would be really upset if he made a mistake. “No,” he said. “I might do it wrong.”

“Here.” His father stood up, and carefully took the baby, and carefully put it in his arms. She was no weight at all. She made a face at him. He could hold her in one arm and touch her on her nose, which made her make another face, and made him smile. But it was a risk, all the same: he very carefully gave her back to his mother, who took her back and smiled, not at him, for doing it right; but at her.

Well, that was the way things were going to be. But she was new, and he could hardly blame people for being interested.

He just said to himself that he had a long, long head start on Seimiro, and she would have a lot of work to catch him.

There were a lot of things he could show her.

Even if they had sealed up some of the servant passages. There were still ways to sneak around the Bujavid.

· · ·

Jase made it back: Madam Saidin had gotten home, and taken over, and Jase was willing to trade news over a glass of brandy.

Kaplan and Polano were still stuck in the hall, being statues, but they were comfortable enough, and there were atevi guards standing near them who knew what they were, and who had orders to get them back upstairs once the festivity had broken up.

Everybody was in the sitting room. Everybody was sitting, Bren, Banichi and Jago, Tano and Algini, even Narani and Jeladi, all indulging in a modest brandy, and everybody debriefing, in safe privacy. Even Bindanda came in, their other plain-clothes Guildsman, to get the news straight from those who were there.

“The baby’s name is Seimiro,” Jago said. And: “Damiri-daja had no trouble at all. And well we hurried. The baby was there before nand’ Siegi was.”

Jase said, “The youngsters were a little worried when they saw everybody leaving—so were the guests. But the dowager took over and explained the situation, and I took the youngsters right on up to Lord Tatiseigi’s apartment: the guests were headed for the wine and brandy, very happy.”

“One wishes the youngsters could have had a better time,” Bren said.

“Oh,” Jase said, “they had fancy dress, they had the museum, they had all the lords and ladies, and seeing Cajeiri and the ceremony—they were very excited. They asked me more questions than I could answer. Then the baby coming—they knew why they had to go upstairs, and then with Madam Saidin helping deliver the baby—they were very excited.”

“One hears the city is going wild,” he said. That was, at least, what his bodyguard reported, and he had no doubt of it.

“The printing office is calling in staff,” Algini said, “and they are preparing another release of cards for tomorrow: the birth announcement.”

“And no trouble?” Bren asked.

“None,” Algini said. “One hopes our remaining problems are busy relocating, and where they have been, we may be interested to learn. For tonight, at least, we can relax.”

Relax. With a glass of brandy, good company, and everybody safe and well. It was a special occasion.

· · ·

“Will you want to stay here tonight?” Father asked, in the hallway. Mother and the baby were asleep, though Father said they would probably have restless nights for quite a while.

Cajeiri gave a little bow. “One has guests waiting, honored Father, and if I may, I should go to nand’ Tatiseigi’s apartment and explain everything. If I may.”

“Yes.”

The enormity of everything struck him then, and maybe, he thought, he should have said something special—about the inheritance and all that. And the ceremony. And the surprise. He gave a deep, deep bow.

“Thank you, honored Father. Thank you very much. And one is very sorry for forgetting the speech.”

“You did very well this evening. One was quite proud of you.”

He straightened up, heat rushing to his face. He could not remember his father saying that. “I shall not be a fool. I shall study. But I do not want to be aiji for a long, long time.”

“You are a good son. A very good son. One is twice proud. Go. Behave yourself. Enjoy the day.”

He did, instantly about infelicitous four paces down the hall before he remembered, then, to make a grown-up exit, and turned and bowed deeply. “Thank you, Father.”

“Indeed,” his father said, and nodded, and Cajeiri walked sedately all the way down the hall, collected his aishid, and walked a little more briskly outside and up the hall past nand’ Bren’s apartment.

“Her name is Seimiro,” he said, thinking of it.

“Is she pretty?” Lucasi asked.

“Wrinkled,” he said, making a face, and laughed.

“Babies are like that,” Antaro said. “I saw my cousin after he was born.”

They were in the hall with no other escort, no guards at the end. They came up on Great-uncle’s door, and it opened, Madam already having gotten a signal from Antaro, and in they came, Madam very happy to have them back.

“Come right on in,” Madam said, “into the sitting room.”

He had a little suspicion when Madam did not take his coat, and when Madam showed him straight to the sitting room, that his guests had not gone to bed.

Indeed, they were all three waiting, in their court dress, with, in the midst of the side table, a very large—cake. It was iced like a teacake. But it was large enough for everybody and the staff. And there was a candelabra beside it and beside that, three boxes wrapped up in brocade fabric.

“Happy birthday!” they all said at once.

He laughed, he was so surprised. And they insisted he open the boxes, one after another: there was a little handwritten notebook from Irene—“A lot of words you could use,” she said; and he saw words he had never seen before, with the rules for pronouncing them. And from Artur there was a little clear shiny marble that lit up. “Just set it in any light,” Artur said, “and it recharges.”

And from Gene there was what looked like a pocket-knife, but it unfolded in screwdrivers and picks and a magnifying glass.

They were wonderful gifts. And then Madam lit the candles and they cut the cake, and all had some—Madam said they had made another cake for staff, and his guests had told them how such a cake had to be—it was iced like one piece, but inside it was in layers and pieces, and Great-uncle’s cook had made the icing orangelle-flavored, his favorite, in clever patterns.

They had fruit drink, and cake, and told stories until it was past midnight and Great-uncle came home, asking whether he had seen his sister, and how his mother was.

“My sister is fine and my mother is, Great-uncle. My father is very happy.”

“Excellent,” Great-uncle said. “Excellent. Such a day this has been! Congratulations, young aiji.”

“Nandi.”

“A fortunate day, indeed. Your ninth year and your sister’s first—all on one day.”

He stood there a moment, realizing . . .

He had a sister. And she was born on his birthday.

His birthday was her birthday. Forever.

Nobody had asked him about that. Worse—his next fortunate birthday would be his eleventh. And from zero, which was today, the very same day would be her infelicitous second: they were always going to be out of rhythm, and nothing could ever fix it.

Except if they celebrated each other’s fortunate day with a festivity.

He had to make a deal with his sister about birthdays. There could be a sort of a festivity every year.

“Is there a problem, Jeri-ji?” Gene asked.

He saw Great-uncle venturing a taste of his extraordinary cake, and very definitely approving.

“No,” he said, and felt mischief coming on. There were so many things his sister needed to learn, not to turn out as stiff and proper as people could want her to be. “No. Not a one.”

Lord Geigi, Lord Regent in the Heavens: His History of the Aishidi’tat with commentary by Lord Bren of Najida, paidhi-aiji

i

Before the Foreign Star appeared in the Heavens, we, on our own, had reached the age of steam.

We had philosophically and politically begun to transcend the clan structure that had led to so many ruinous wars.

We had eleven regional associations which agreed to build a railroad from Shejidan to the west without going to war about it.

Within the associations, there had been artisan guilds for many years. But during the building of the first railroad, many guilds, starting with the Transportation Guild and the Builders, had not only transcended the limits of clan structure, Transport and the Builders ended by transcending the regional associations. They were the first political entities to do so.

Clans had long formed temporary associations of regional alliance and trade interest. These were associations of convenience that often broke up in bitter conflict.

That was the state of things when, three hundred years ago, the Foreign Star arrived in the heavens.

It appeared suddenly. It grew. Telescopes of the day could make out a white shape that seemed to reflect light instead of shining like a star. The Astronomers offered no one theory to account for it. Earliest observers said it was a congealing of the ether that conveyed the heat of the sun to the Earth. But as it grew and showed structure and shadow, the official thought came to be that it was a rip in the sky dome and a view of the clockwork mechanism beyond.

The number-counters agreed it was an omen of change in the heavens, and most said it was not a good one. Some tried to attach the omen to the railroad, for good or for ill, and for a whole year it occupied the attention of the lords and clans.

But it produced nothing.

And under all the furor, and with a certain sense of something ominous hanging above the world, the railroad from Shejidan to the coast continued. Aijiin, once warleaders elected for a purpose, were elected to manage the project, holding power not over armies, but over the necessary architecture of guilds, clans, and sub-clans, for the sole purpose of getting the project through certain districts and upholding the promises to which the individual clan lords had set their seals.

Empowering them was a small group which itself began to transcend clans and regions: this was the beginning of the Assassins’ Guild, and their job was to protect the aijin against attack by others of their profession serving individual lords.

The Foreign Star harmed nothing. The railroad succeeded. If the Star portended anything, many said, it seemed to be good fortune.

The success of the first railroad project led to others. Associations became larger, overlapped each other as clans and kinships do. And significantly, in the midst of a dispute that might have led to the dissolution of these new associations, the Assassins’ Guild backed the aiji against three powerful clan lords who wanted to change the agreement and break up the railroad into administrative districts.

We atevi have never understood boundaries. Everything is shades of here and there, this side and that. It had not been our separations and our regions that had brought us this age of relative peace. It was associations of common purpose, and their combination into larger and larger associations, until the whole world knew someone who knew someone who could make things right.

And now this one aiji, backed by the Assassins’ Guild, had made three powerful lords keep their agreements for what turned out to benefit everyone—even these three clans, who collected no tolls, but whose people benefited by trade.

That aiji was the first to rule the entire west. The first railroad and the power of the aiji in Shejidan joined associations together in a way simple trade never had. Now the lords and trades and guilds were obliged to meet in Shejidan and come to agreement with the aiji who served and ruled them all. This was the true beginning of the legislature and the aishidi’tat, although it did not yet bear that name.

And without lords in constant war, and with the Assassins enforcing an impartial law, townships sprang up without walls, not clustered around a great house, but developing in places of convenience, with improved health and new goods. Commerce grew. Where conflicts sprang up, the aiji in Shejidan, with the legislature and the guilds, found a way to settle them without resort to war.

Shejidan itself grew rapidly, a town with no lord but the aiji himself. It attracted the smaller and weaker clans, particularly those engaging in crafts and trades. And those little clans, prospering as never before because of the railway, backed the aiji with street cobbles and dyers’ poles when anyone threatened that order. The guilds also broke from the clan structure and settled in Shejidan, backing the aiji’s authority, so that the lords who wanted the services of the Scholars, the Merchants, the Treasurers, the Physicians, or the Assassins, had to accept individuals whose primary man’chi was to their guilds and the aiji in Shejidan.

The Foreign Star had become a curiosity. Some studied it as a hobby. Then as a village lord in Dur wrote, who lived in that simpler time . . .

One day a petal sail floated down to Dur from the heavens, and more and more of them followed—bringing to the world a people not speaking in any way people of the Earth could understand. Some were pale, some were brown, and some were as dark as we are. Most landed on the island of Mospheira, among the Edi and the Gan peoples. Some landed on the mainland, near Dur. And some sadly fell in the sea, and were lost.

For three years the Foreign Star poured humans down to the Earth, sometimes whole clouds of them. Their small size and fragile bones and especially their manner of reaching the Earth excited curiosity, and won a certain admiration for their bravery. Poets immortalized the petal sails.

These humans brought very little with them. Their dress was plain and scant. They seemed poor. Wherever they landed, they took apart the containers that had sheltered them, and used the pieces and spread the petal sails and tied them to trees for shelter from the elements. They tried our food, but they sometimes died of it, and it was soon clear they could eat only the plainest, simplest things. They were a great curiosity, and one district and another was anxious to find these curious people and see them for themselves. Some believed that they had fallen from the moon, but the humans insisted they had come from inside the Foreign Star, and that they were glad to be on the Earth because of the poverty where they had been.

There was no fear of them by then. They spoke, and we learned a few words. We spoke, and we first fed them and helped them build better shelter. We helped them find each other across the land, and gather their scattered associates. We were amazed, even shocked, at their manners with each other. But they seemed equally distressed by ours.

–Lord Paseni of Tor Musa in Dur

The Foreign Star, as the man from Dur wrote, had for years been a fixture in the heavens. The Astronomers had long ago proclaimed that it had ceased growing, and that, whatever it was, it did not seem to threaten anything.

Then humans rode their petal sails down to the west coast of the continent and the island of Mospheira. They were small and fragile people and threatened no one. With childlike directness they offered trade—not of goods, but of technological knowledge, even mechanical designs.

The unease of the man from Dur might have warned us all. But some humans learned the children’s language, which allowed them mistakes in numbers without offense.

The petal sails kept falling down, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of them, until there were human villages. They brought their knowledge. They built in concrete. They built dams and generators: they built radios and other such things which we adopted . . .

And finally they stopped coming down.

The last come were not as peaceful as the first.

We had no idea why.

But the ship that had brought the humans and built the Foreign Star had left. It was of course the space station they had built in orbit above our Earth.

And the last to come down were the station aijiin and their bodyguards, armed, and dropping pods of weapons onto the world.

ii

<

Another ship would follow Phoenix, with more colonists. That second ship would bring equipment which would let the orbiting station eventually set down people and build a habitat on a world far less hospitable than the Earth of the atevi.

But something happened. The ship-folk believe that the ship met some accident and was shifted somewhere far off its intended course. The ship tried to find some navigational reference that would tell it where it was. The fact that reference stars were not visible where they should be indicated to them that something very drastic had happened.

Phoenix gathered resources such as it could and aimed toward the closest promising star. It saw, among its several choices, a blue world much like humans’ own ancestral Earth. The world had the signature of life—which meant they would indeed find resources there. The world had no artificial satellites. They picked up no transmissions. This informed them there was no space-faring civilization there.

They ended up in orbit about the Earth of the atevi.

They saw, below them, towns and villages. They saw technology of a certain level—but not high enough to come up to them, and their law, remote as they were then from any law but their own conscience, ruled against disturbing the world, even if they had had an easy means to land and ask help . . . which they did not.

The colonists had come prepared and trained to build an orbiting station. They gathered resources from asteroids, manufactured panels and parts and framework, enclosing themselves from the inside out and housing more and more workers. This became the core of the station. They built tethers, and began the construction of the station ring, to gain a place to stand. Barracks moved into the beginnings of the ring. The first children were born. Spirits rose. They were going to survive.

Phoenix crew was supposed to have supported the colonists this far and then move on. The ship-folk were spacefarers by trade and nature and had no desire to live on a colonial station. But now that the colonists were safe, and now that the ship was resupplied and able to leave—it troubled the ship-aijiin that the ship now had no use and nowhere to go next. They had only one port, and clearly the station was not where they wanted their port to be. The blue planet had exactly the right conditions and everything they needed . . . but it was owned, and the ship-folk’s law said they should not disturb it.

The ship had long argued against the building of any elaborate station in orbit about the planet. They wanted the colonists to leave off any further development of the station they had, use it as an observation point and a refuge should anything go wrong, and build another, larger station out at Maudit. They should, the ship-aijiin said, leave the inhabited world alone until, perhaps, they might make contact in space some time in the future.

The colonists, born aboard this station, and with all the hardship of the prior generations, had no desire to give up their safety and build again—least of all to build a station above a desolate, airless world. They wanted the world they saw under their feet. They wanted it desperately.

The station aijiin also argued against building at Maudit. They needed their population. They needed their workers—and they wanted no rival station. They absolutely refused the ship’s solution.

The argument between station authorities and ship-aijiin grew bitter. Phoenix, now hearing these same officials claiming authority over the mission and the ship itself—decided to pull out of the colonial dispute altogether. They considered going to Maudit with a handful of willing souls and building there, then trying to draw colonists out to join them in defiance of the station aijiin—but that idea was voted down, since the colonists even at Maudit would still be in reach of that living planet, and the crew was vastly outnumbered if it came to a confrontation on the matter. By now the ship-folk did not entirely trust even the colonists they considered allies, with the green planet at issue.