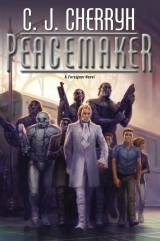

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

But unconsciousness, in the safety of his own bed—he might manage that for a few hours.

There were so many things in motion, so much going on, still, that had to be tracked—over which the Guild did not preside. But Banichi was safe. Everybody was back, or on the way back.

He reached his room, not without the attention of his valets, who waited there.

There was one more piece of business, he thought, closing his fist—the heavy ring, washed clean now, tended to slide and turn and he would not take it off, not for an instant. He could not send it back by courier, even his most trusted staff.

But he could not rouse Tabini-aiji out of bed, either. The matter seemed at an impasse, something he could not resolve.

His valets saw him to bed. He sat on the edge of the mattress, looked at the ring in the dim light, thinking . . . so many things yet to do, so many things so long stalled by the situation they’d just, please God, finally set in order, the last piece of what they’d needed to set right before the world would be back in the sane order they’d left when they’d gone off to space.

Better. They no longer had the Human Heritage Party to cause trouble on the other side of the strait.

And the man who’d been trying to run atevi politics on this side of the strait, from a decades-old web of his own design—was dead, tonight. The web would still exist. But the Guild leaders now back in power had every reason to want it eradicated—so it had stopped being his business. The Guild itself would take care of its own problem.

His problems centered now around Tabini’s problems, and the dowager’s. If they could now get certain legislators to move on those—and get those critical bills passed . . .

And get lords appointed in Ajuri and the Kadagidi territory who weren’t working against the aiji . . .

He became aware that he had not dismissed his two valets. They were still standing there, staring at him with concern.

“I shall return this in the morning,” he said of the ring. “Kindly tell Narani, nadiin-ji, that I have to do that in the morning, before anything else.”

Koharu and Supani said they would relay that message, and he simply put himself into bed face down, so his head would not bleed on the clean, starched pillow casing.

It was so good. It was so very good for everyone to be alive, and for them all to be home.

· · ·

“One has finally heard,” Veijico said, “officially, what has happened—at least what Guild Headquarters is saying happened.”

They were all in night-robes—they had been trying to sleep when Veijico and Lucasi had slipped into the guest suite, so sleep was no longer in question. Antaro and Jegari had gotten up to ask what Veijico and Lucasi had learned. Cajeiri had heard that, and he could not stay abed: he had gotten up and asked them to tell him—

But they had gotten nowhere with that explanation, before Gene and Artur had come out of their room and asked what was going on, and then Irene had come out—so there they were, all of them, wrapped in over-sized adult robes, shivering in the lateness of the hour and the spookiness of the whole situation.

“There were a lot of Guild officers who had never come back to Shejidan since the Troubles,” Veijico said. “Your father and your great-grandmother brought them back tonight. The Guildmaster that has been in charge since your father came back to office is overthrown, the Director of Assignments is dead—”

“They got him!” Cajeiri said.

“They did, nandi. We are not supposed to name names of anybody. But that person is gone. And the people who have been high up in the Council have stepped down. Except two who are under arrest. The old officers have come back and they are in charge.”

“This is good,” Cajeiri said for his guests. “A good thing has happened.”

“But we are not supposed to say anything more than that,” Lucasi said, “because the Guild does not discuss its business.”

“But you are happy about it,” Cajeiri said.

“We believe it is good,” Lucasi said, “because of who went to change it.”

“Nand’ Bren and Cenedi-nadi.”

“Yes,” Veijico said. “They did.”

“And they all are back.”

“Now they are, nandi. Banichi is injured. He is home and doing well. Cenedi-nadi, Nawari, all the ones from your great-grandmother’s aishid, are all back and accounted for. We are under a continuing alert: there are a few individuals the Guild is actively hunting tonight, a few who were not in the building tonight, and some who may have gotten out and run or gone into hiding. We—being where we are, and assigned under the former leadership—one is certain all four of us will be up for review, nandi, regarding our assignment with you. Our man’chi will be questioned. We hope we shall not be removed.”

“What is she saying?” Artur asked—it was not the sort of conversation they had ever had, on the ship, and there were words Cajeiri was hardly sure how to translate.

“Everybody is back. There’s still an alert but everything’s all right. It’s still good.” He changed to Ragi. “My father will see you have no trouble, Jico-ji, and I shall remind him. And I shall remind mani, too. I shall by no means let them send you away!”

“We would be honored,” Veijico murmured with a little nod. “And your guests should not worry about this. We should not alarm them.”

“Good people run the Guild now,” Antaro said, little words their guests knew. “They are hunting the bad ones.”

Irene had said nothing, just sat listening, hugging her robe close and shivering a little. “I don’t think we ought to tell our parents everything,” she said with a little laugh, and they all agreed.

“Are you cold?” Cajeiri asked. “We can order tea. Even at night, someone is on duty.”

She shook her head. “Just scared,” she said. “I’m always scared of things.” Another little laugh. “I’m sorry.”

“Not sorry,” he said, and gave the old challenge. “Who’s afraid?”

She held up two fingers, just apart. “This much. Just this much.”

“We’re safe,” he said. “Are we safe, Jico-ji?”

“Safer,” Veijico said. “Definitely safer.”

“Good, then!” They had just a little light, sitting there around the table, in the dark. Human eyes were spooky, shadowy, and never taking the light. Veijico’s and Lucasi’s, Antaro’s and Jegari’s, theirs all did, so you could see their eyes shimmery gold, honest and open. But with humans, one had to trust the shadows, and know their intentions were good. Irene shivered, she was so scared, sometimes. Irene had said—she just was that way.

But who had stood there facing his mother without a hint she was scared at all?

Irene.

He understood Irene, he thought. There were two kinds of fear. There was facing bullets, which meant you had to do something. And there was the long slow kind of fear that came of knowing there were problems and there was nothing you could do right away except try not to make things worse. His associates had seen both kinds in their short visit, and not shown anything but a little shiver after it was all over. Even Irene. She was very bright. She thought about things. She thought a lot. And she was certainly no coward.

He was proud of his little household, and he was increasingly sure he could count these three as his. He had attracted very good people. Mani had always said that was the best proof of character . . . that one could know a person by his associates. He felt very happy with himself and them, overall.

And when they all went back to bed—who was it who had to go to bed alone, with all this going on?

Him. And Irene.

“We can all sleep in this room,” he said. It was a huge bed, and there was room enough, and they could just layer the bedding and make it all proper, the way folk did who had only one bed.

So they did that. His aishid got their proper beds for the rest of the night, and he and his associates tucked into various layers of satin comforters and settled down together, like countryfolk with visitors, in the machimi plays.

He had hardly ever felt so safe as then.

14

Getting up in the morning—was not easy. A splitting headache—did not describe the sensation.

Bren slid carefully out of bed, felt his way to the light, and rummaged in the drawer of the little chest for the pill bottles. The scalp wound had swollen. He had no desire at all to investigate it, for fear his head would come apart. He simply swallowed, dry, two capsules of the right color and crawled back into bed face down for a few more moments.

The rest of him was amazingly pain-free. Usually when he and his aishid had been in a situation, he emerged sore in amazing places. But the back of his head paid for all.

And he had to find out how Banichi was doing. That thought, once conceived, would not let him rest. He crawled backward off the high bed, felt after his robe, and padded barefoot down the hall toward the security station and his aishid’s rooms.

The door was open, and there were servants about in the back halls, being relatively quiet. He heard nand’ Siegi’s voice, and Banichi’s, which was reassuring. He reached the little inner corridor, nodded a good morning to Algini and Jago, who were there in half-uniform, and asked, as he stood in the doorway, “How is he?”

“Arguing,” Jago said. “Nand’ Siegi will not permit him to sit up until afternoon.”

“Nor will we,” Algini said, and cast him a look. “You are next, nandi. Nand’ Siegi will deal with that.”

He truly was not looking forward to that. “Cup of tea,” he said, thinking hot tea might steady his stomach. The headache remedy was not sitting well.

He did not, however, get that far. Nand’ Siegi turned in his direction, saw him, and came his way with business in mind.

And treating it did hurt. God, did it hurt! Nand’ Siegi graciously informed him that it would scar somewhat, that he was very lucky it had not fractured his skull, that there were certain symptoms he was to report immediately should they occur, and that he should sleep on his face for several days. He was out of the mood for tea, after that, but by that time Jase was up, breakfast was about to be served, and Supani and Koharu were asking him whether he would dress for breakfast, or have it informally.

He was not sure he could keep toast down, his neck was stiff from tension and he did not want to tilt his head out of vertical. But he advised his valets that he would be paying a visit to Tabini-aiji as soon as the aiji wished. And he got up carefully, trying not to tilt his head, and made it to the little breakfast room, where Jase was having morning tea.

“How’s the head?” Jase asked.

He sat down, staring blankly at the out of focus door, and took about a minute to say, “Sore. Damn sore.”

“Tea?”

The door was still his vision of choice. It was uncomplicated. It didn’t move. And he didn’t have to turn his head to look at it. “Did Kaplan and Polano ever get any sleep?”

“You’re white. Here.” Jase reached across the little breakfast table. A cup of tea thumped down in front of him. “Drink.”

He picked it up and tried, gingerly, without looking at it. It was strong, sugared, and spiced.

“Nand’ Bren needs toast and eggs,” he heard Jase say.

He was far from sure about that. He was not sure about the spice in the tea. He blinked several times, and brought the door completely into focus. That was a start.

“We’re doing fine,” Jase said. “The kids got some sleep, I understand. I did. Algini says he’s been in touch with the Guild periodically during the night, and they’ve run down one of their fugitives. They have three others holed up in a town to the south.”

“Trying to run for the Marid,” Bren murmured, turning his head slightly, trying his focus on Jase’s face, which was a shade blurry. “No surprise. But that won’t be as ready a refuge now.” Two more sips of tea. “Anything else?”

“Nothing that’s reached me,” Jase said.

He was sure there would be messages. The message bowl in the front hall was likely overflowing since dawn. He remembered the bundle of post-mortem letters he had put in Narani’s hands. Retrieving those and destroying those was absolutely urgent.

He said, “Anything from Geigi?”

Jase shook his head. “Nothing. But I don’t expect anything. We haven’t advertised the problem. It’s really been rather quiet until this morning.”

“Last night,” he said, “last night in your venue. How did it really go?”

“Amazingly well,” Jase said, and the eggs and toast arrived. The youngest of the servants spooned eggs onto Bren’s plate, scrambled, thank God, nothing requiring such focus as cracking a shell and eating a soft-boiled egg without spilling it. “Sauce, nandi?”

“Thank you, Beja, no. —The kids,” he prompted Jase. “Damiri-daja. The dowager.”

“Damiri-daja said very little,” Jase said, “except at the last. Irene had a little speech, thanking the household. Damiri-daja asked Irene if her mother approved her being here, remarked how small she is, and told Cajeiri he’d done very well. It was an odd string of questions.”

It was odd—on an evening when her son’s guests were sheltering with her because her husband’s closest allies were out assassinating her elder cousin, who had probably just assassinated her father.

She was about to have a daughter of her own. Was it some maternal impulse?

Or had it been a political statement, intended to annoy her husband—from a woman very close to a politically-driven divorce?

Never forget, either, that her uncle Tatiseigi had been there as witness. God, he wished he’d been there to parse the undercurrents.

“Was Cajeiri upset?”

“Puzzled.”

“Small wonder, that.” He had a bite of toast, and the egg, and with the hot tea, his stomach began to feel warmer and a little steadier. It was awkward to eat, wearing the heavy ring, but he would not take it off. “At least it wasn’t outright warfare.”

“It wasn’t that,” Jase said, “I’m reasonably sure. Irene didn’t seem upset at it. She’s a shy kid. Timid. But she held her ground. We had to translate a question. She answered in very good Ragi, with all the forms I’d have used.”

“Good for her,” Bren said. “Good for Cajeiri. He’s done all right.” He shifted a glance up, as Narani appeared in the door, looking apologetic.

“The aiji wishes your presence, nandi,” Narani said. “At your convenience, the message said. He is in conference with the aiji-dowager.”

God. That meant—show up. Now. Possibly even—rescue me. Fast. He frowned, and those muscles hurt, right along with his neck. “Koharu and Supani,” he said to Narani. “Immediately, nadi-ji, thank you. Tell Algini.” He used the table for leverage to get up, not inclining his head in the process. “Best I get over there,” he said. “He means now.”

“Understood,” Jase said. “If you need me—”

“I’m all right,” he said. “Finish your breakfast.”

There might be another breakfast. Or lunch. He had no clear idea what time it was. He had to dress, get the damage to his scalp covered in a suitable queue, and look civilized, at least.

His valets met him in the hall, went with him into the bedroom—they dressed him, got his boots on without his having to bend over, and arranged his hair very gently so, they assured him, the wound hardly showed. He went out to the foyer, gathered up Algini and Jago—in a timing Narani arranged without any fuss at all, and went out and down the hall—a little dizzy: he was not sure whether that was the headache or the headache cure; but he made it the short distance down the hall and through Tabini’s front door without wobbling.

He could hear the argument in the sitting room, something about Lord Aseida. It was the dowager’s voice, and Tabini’s, that was too quiet to hear. Cenedi was on duty, with Nawari, outside the sitting room door, and that was useful. Algini could have a word with them while he waited.

Jago, however, elected to come in with him.

He walked in, made the motions of a little bow, without putting his head too far out of vertical, and received the wave of Tabini’s hand that meant sit down. “Aijiin-ma,” he said inclusively, and carefully settled.

His late arrival meant a round of tea and, gratefully, a cessation of the argument for a moment.

“You have had a physician’s attendance, surely, paidhi,” Tabini said.

“This morning, aiji-ma. Thank you. And one thanks the aiji-dowager. Banichi and I are doing very well this morning.”

“Your color is shocking,” Ilisidi said.

“I would not risk the best tea service, aiji-ma,” he said, and murmured, to the servant, “more sweet, nadi, if you will. Twice that.” Ordinarily he preferred mildly sweet, but this morning he had an uncommon yen for the fruity taste. And salty eggs. Electrolytes, his conscious brain said. “And do stay near me, nadi. Please take the cup from my hand immediately if I seem to drift.”

“You should not have come,” Tabini said. “You might have declined, paidhi-ji.”

“I could not keep this all morning,” he said, regarding the ring on his hand. He drew down a sip of tea, which did taste good, and faced the quandary of courtesy versus prudence—tea delayed the necessity to get up and return Tabini’s ring . . . he thought so, at least. He was just a little muddled about priorities. And about too many other things. And thoroughly light-headed, and not thinking well, since the exertion of coming here. “In just a moment, aiji-ma.”

“Fool paidhi.” Tabini set down his cup, got up, and came to him and held out his hand.

“Aiji-ma.” Bren had set down his cup, eased the ring off and dropped it into Tabini’s warm hand, which closed, momentarily on his.

“Cold,” Tabini said.

“The tea helps, aiji-ma.”

“Fool,” Tabini said, crossing the little space to sit down again. “Fool. You shielded your own bodyguard last night. I have every suspicion of it.”

“I truthfully cannot remember what I did, aiji-ma. We just sat against the wall, and there was a great deal of racket.”

“Ha,” Ilisidi said. “Racket, one can well imagine. We have had a lifelong curiosity to see the inside of that place. You have cheated us of the sight.”

“I did not get beyond the Council chamber, aiji-ma. And this morning I am losing little details of what I did see there. Which likely will suit the Guild well. But one does understand we came out with everyone alive. Is that true?”

“True,” Tabini said. “One is glad to say, it is true.” Tabini set his cup down, and now conversation could shift. “We have the old Guildmaster back, we hear. The dead have risen up, the missing have returned, the retired have rescinded their retirement, and a handful of high officials installed this last year have proven difficult to find. We hoped that the Council meeting would have had all of them on the premises, but we missed five individuals, we understand. The restored leadership is interviewing members, starting with assignments to the Bujavid, ascertaining man’chi, kinship, past service, asking for references, and any other testimony that may apply. Meanwhile we have a matter arising which will regard the paidhi-aiji, and if you are able to hear it, paidhi, it would be good to set your staff on it this morning.”

“One waits to hear, aiji-ma,” he murmured—hoping it was a small problem.

“The matter of Lord Aseida,” Tabini said, “is a storm blowing up quite rapidly, if predictably. The lords are all uneasy in what happened, and we are particularly concerned that the action may set your good name in question.”

“That fool Topari,” Ilisidi said, “is the one pushing this.”

“Topari is irrelevant,” Tabini said. “Of Tatiseigi’s enemies, he is the very least.”

“The man thinks in conspiracies,” Ilisidi said. “He will argue against the television image if we provide it. He understands such things can be edited. I have it on good authority, he will be the problem. The others will let this fool put his head up and see what the answer is. He is exceedingly upset—the arrest of a lord is his issue—so he claims.”

Topari. A lord of the Cismontane Association, south of the capital—a rural district even more conservative than the Padi Valley Association. It was a Ragi population, in the watershed this side of the Senjin Marid, and running up into the highlands.

That district, one readily recalled, detested humans on principle, did not support the space program, and Topari was part of that little knot of minor lords that, geographically speaking, sat between the Marid and the aishidi’tat. Regarding his relations with Tabini—Topari had not been signatory to Murini’s coup—but likely only because that region rarely joined anything.

The brain was working. The head still hurt, but he felt the little adrenaline surge.

“You can do nothing with him, paidhi,” Tabini said. “And we still say he will not be the principal problem.”

“Leverage,” Ilisidi said, “is his entire motive. Aseida could catch fire and he would care nothing for the man. But Topari sees a way to make a problem to our disadvantage and cause a problem.”

A problem aimed at the aiji-dowager, Bren thought. And asked: “What, aijiin-ma, is his position?”

Right question. Tabini looked very annoyed, and Ilisidi had a quick answer.

“He is currently in a lather over our agreement with the Taisigin Marid,” Ilisidi said. “That is the entire business.”

“I am not about to take issue at a Ragi lord for objecting to the removal of a Ragi lord,” Tabini said. “That is not the approach I can make to this situation, especially with my grandmother as one of the principals in this affair!”

“The paidhi asks the right question. What is his position? Nothing to do with Lord Aseida or lordly prerogatives. We are his real target. He objects to our trade agreement with the Taisigin Marid because he sees it as affecting the Senjin rail line which his grandfather built. He envisions the southern treaty as replacing his precious railroad—the only privately constructed rail still functioning in the aishidi’tat. Because of an imagined danger to his rail segment and his little slice of use-fees on shipments to Senji, he has made me his enemy—I believe tyrant was the precise wording when he discussed my character. And while a reasonable man might have retreated from his rhetoric of several decades past, he views the whole world as an absolute set of numbers. He views negotiation as a fault and a weakness. He calls me fickle, and changeable, but will apparently not believe I can back off from an inconvenient feud which never mattered greatly in the first place! That, Grandson of mine, is his entire concern with the fate of Lord Aseida, but I will wager you he will present a resolution calling for an investigation, and if he has his hand on it, it will be a resolution extravagant in its blame of us and Lord Tatiseigi for attacking that Kadagidi whelp who was trying to kill us!”

“You are not worried about your reputation,” Tabini said.

“Of course not!”

“Well, his resolution will fail, when its own caucus fails to support it. And if the paidhi-aiji will simply supply Lord Tatiseigi with the record Jase-aiji has—you may have the satisfaction of publicly embarrassing Lord Topari.”

“And creating a firestorm around our rail extension!”

God. Railroad politics. Trains were not only vital to the southern mountains, they were the only transport in the southern mountains, besides local trucks on roads that would daunt a mecheita. It was all going to start all over again. One saw it coming, everybody south of Shejidan wanting advantage to their own clan in the routing of the rail extension.

And Topari was the man to start it all sliding.

“Perhaps,” Bren said quietly, “perhaps I can get ahead of the situation, before anyone proposes an investigation.”

“You are wounded, paidhi!”

From Tabini, it was downright touching. Bren lifted a hand, a gesture to plead for a hearing of his point. “I recall the incident of the name-calling.” The old man had, in a legislative session some years ago, called Tatiseigi ineffectual and Ilisidi an Eastern tyrant. Tatiseigi had, in turn, called him greedy, which, within the Conservative Caucus, had seen charges flying about graft and the siting of rail stations. Tatiseigi had emerged from the squabble with perfectly clean hands, since he had fought to keep rail out of his district, not to bring it in. “As I recall, his quarrel with Lord Tatiseigi also dates from the railroad dispute.”

“Absolutely,” Ilisidi said. “Absolutely that is behind his stirring this up.”

“He is not the only one stirring this up,” Tabini said.

“He is the one poised to be a cursed inconvenience,” Ilisidi shot back.

“Tatiseigi can deal with him,” Tabini said, “as deftly as he did the last time.”

“Or I can deal with him,” Bren said, and in the breath he had, with the room somewhat swimming in his vision: “Lord Tatiseigi has human guests at the moment. And Lord Tatiseigi’s complaint is our justification against the Kadagidi, so he cannot take an impartial stance. I have actually exchanged civil words with Lord Topari in the past, unlikely as it may seem.”

“Negotiation with the man?” Tabini asked. “It may only make him a worse problem. He is not accepting of humans.”

“But I sit on the Transportation Committee,” Bren said quietly. “I have not been active on it since our return—but in fact, I will have influence in the plan for the south, and I am the negotiator with the Taisigin Marid, all of which will directly affect his district. My intentions may greatly worry him.”

“The bill on which you and my grandmother have staked an enormous risk—is still not voted on. The whole linked chain of the tribal peoples, Machigi’s agreement, the whole southwest coast, gods less fortunate! is postponed, and may be postponed further, awaiting a resolution of this mess of the succession in two clans. If you make Lord Topari in any wise part of the Aseida stew, it may well spill into the west coast matter, and if those two become linked, every lord and village will take a personal invitation to argue their own modifications to the west coast compromise. We cannot rescue you from that situation, if it goes awry. If you do lend this mountain lord any importance on these grounds or start negotiating with him before the west coast matter is voted on and untouchable, the Aseida matter can blow up into a storm that will take the west coast and the southern agreement with it.”

“One absolutely concurs in your estimate, aiji-ma, and I take your warning. I shall not negotiate with him. But one can advise Lord Topari—privately, politely—with no audience at all—that he is about to step into political quicksand. The Cismontane poses a nuisance to the southern agreement if he becomes a problem, but I may be able to do him a favor.”

“By warning him off this.”

“Warning him, exactly, aiji-ma. If he will talk to me—if he is not a fool, and I have not had the impression that he is. He is a devout ’counter, yes, a traditionalist, yes. But if I warn him away from a political cliff edge, and he avoids a second embarrassing loss to Lord Tatiseigi, then he may even deign to talk to me on the railroad matter, when it comes at issue . . . so long as I am entirely discreet about the contact. He needs publicly to deplore human influence, true. But if I can prevent him taking Aseida’s part in this, and if he warns certain other people off the idea—that will help us. One does recall that he lacks a Guild bodyguard. Several of his neighbors are in the same situation. They will not be getting the information that other lords have already gotten, quietly, from the changed leadership in the Guild. So he is in a position to make a public fuss and then to be embarrassed again, very painfully. But I propose to inform him—in a kindly way. Am I reasoning sanely in this, aijiin-ma? I think so, but a headache hardly improves my reasoning.”

“Will he even speak to you?” Tabini asked. “You are in no condition to go to him. Nor should you!”

“My major domo is a remarkable and traditional gentleman. It would be the crassest rudeness to turn Narani away unheard. I can at least try such an approach and plead my injury to necessitate Lord Topari coming to me.”

A deep breath. A sigh. “Well, well, do your best, paidhi. If you fail, then he may have to have his falling-out with Tatiseigi in public, and it will be untidy, and it may spill over into other debates, but I shall leave it in your hands, if you believe you can work with him. I have two vacant lordships to deal with, neither easy to fill, and I shall not be asking Topari for his opinion.”

“Will you ask Damiri?” Ilisidi asked archly, lips pursed, and Tabini scowled in her direction.

“We are certain you will have advice.”

“Who is her recommendation?”

“I have not asked her. Nor shall until she offers an opinion. Gods less fortunate, woman! She has a father to mourn!”

“Ah. We had hardly expected mourning on that score. But she will not take the lordship. Nor will my great-grandson. Let us agree on that, at least.”

Tabini frowned. “To my certain recollection, I have that decision, alone, and I find no reason to forecast who it will be.” He placed his hands on his thighs, preparatory to rising. “And we have kept the paidhi-aiji, who is distressingly pale, overlong, and made him work much too hard. Paidhi, you and your aishid will pursue the matter you wish to attempt. Cenedi will pursue business of his own. I have a meeting this afternoon with the Assassins’ Guild, regarding . . . business. And the aiji-consort will meanwhile make plans for the Festivity . . . which we are now hopeful will come off without hindrance or extraordinary commotion. Paidhi-ji.”

“Aiji-ma?”

“Rest. Care for your own household. And do not be talked into visiting Topari on his terms. We forbid it.”

“One hears, aiji-ma.”

Tabini rose, and offered his hand to his grandmother. She used his help, and her cane, and Bren rose and bowed as Jago moved close by him, in case the paidhi-aiji should unceremoniously fall on his face. Cenedi was now attending the dowager. Everything was back where it ought to be.

And he—he had to talk to Jase and send Narani on an errand into the city.

Preferably after a ten minute rest, with his eyes shut.

He was aware of his heartbeat in the wound on the back of his skull and tried to decide whether it matched the pounding in his temples. He just wanted to go home, lie down, preferably not on his back, and then maybe have another slice of buttered toast, to settle his stomach.