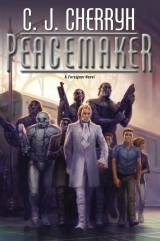

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Madam had told them the time to be in the sitting room, and it was time. Antaro opened the door and they all went in good order—he had worked out how they should go, being an extreme infelicity of eight—he had Liedi and Eisi go with his guests, to make a fivesome of them, and those two would have dinner with his father’s staff.

So they numbered ten when they went into the sitting room; and Great-uncle, who still looked very splendid despite the missing baggage, waited for them with his bodyguard.

“Nephew,” Great-uncle said, giving him a look that clearly noted the traveling coat.

“I shall change coats, Great-uncle, once we arrive.”

“Very good,” Great-uncle said, nodding approval. “Well done, nephew, that you think of such things.”

He felt very pleased, hearing that. He hoped his mother and father thought as well of him.

There was a knock at the front door, and he heard it open. He heard the strange machine-noises of Jase-aiji’s bodyguards’ armor, a presence which he had not expected: Kaplan and Polano had never gone about in armor on the ship, but he supposed that, like the Assassins’ Guild, they must have rules about what equipment they used in what sort of place.

Jase left his bodyguard out in the foyer and came into the sitting room, escorted by Madam Saidin—he was wearing court dress, and he bowed to Great-uncle, and to him and his guests. Jase-aiji seemed very pleased with what he saw.

“Nandi,” he said to Great-uncle. “We will wait just a moment. One wished to allow time for any last-moment difficulty, but,” he said with a glance at the guests, “one sees everyone in very good order.”

“We understand,” Great-uncle said, which was a little strange for Great-uncle to say. Were they going to stop and take tea and wait?

Were his mother and father having an argument? Was that what the waiting was about?

But Great-uncle simply stayed standing, as if he knew the wait would not be that long, and engaged Jase-aiji in a discussion of the arrangements for the festivity—where Jase-aiji’s men were evidently going to provide some of the security.

That would be odd—Jase-aiji’s guards, in armor, at his birthday, by Great-uncle’s arrangement, and it would certainly get attention—the way he could hear their little movements out in the foyer—just now and again, because they could just stand and stand and stand, like statues, and one forgot they were alive—until they moved.

People were going to talk about that, he thought. They were very scary when they stood like that. And inside they were just Kaplan and Polano, who were not always mannerly, but always friendly and cheerful: he felt very comfortable with them when they were not in armor.

Definitely they were going to be a sensation at his festivity.

· · ·

“Nadiin-ji,” Bren said to the household. Most of his servant staff had gathered in the foyer to see them off. There was no keeping the secret now that the paidhi-aiji and his bodyguard were not going to the aiji’s party this evening, that they were about to do something in support of the aiji-dowager’s staff—and that even this safe hallway might become dangerous.

The domestic staff’s job was to keep the apartment’s front door shut and keep out of the servant passages—to lock them, in fact; and—an instruction he had given to Narani alone, but that Narani would give once they left—they were to watch those locked doors of the servants’ passages, which led down to the second floor and its resources. Those doors were solid, and once they were locked, there were alarms at a certain point; and if any alarm went off, they were to gather quickly in the foyer, abandon the apartment, and go next door to the aiji’s apartment, to warn the aiji’s staff.

“Narani will be in charge of house security until we return,” he said. “Narani-nadi will give specific orders after we have left. I rely on you.”

There were solemn nods. Bindanda was the other staff member in charge during a crisis, not well-known to be Guild, which was the way Bindanda wanted it. And Bindanda had his own instructions regarding arming a deadly installation in the servants’ hallway access—if an alarm went off. One hoped no such thing would happen.

As for the rest of the staff—for the honest young countryfolk from Najida, mere boys and girls, youthful faces solemn with concern, and for his oldest servants as well, one had the strongest temptation to say something quite maudlin—

Which would only scare the young people, worry them and raise questions one by no means wanted to answer.

At this point, briefcase in hand, on the verge of leaving his own safe foyer, Bren found himself as superstitious as the most devout ’counter, and he was determined not to give way to it.

So he just said to the servants who had gathered, “Baji-naji, nadiin-ji. Take good care of my guests.”

“We shall, nandi,” Narani said, and at a nod from Banichi, opened the front door.

Tano and Algini went out first—with sidearms, ordinary equipment. They might have been going on a social visit. They walked briskly down the corridor to a point that happened to coincide with a fine old porcelain figure on a stand. They stopped there.

It was time. The clockwork gears began to move.

Bren exited the apartment with Banichi and Jago, similarly armed, on his left and his right. Narani took a stance outside the open door, keeping watch in the direction where the hall ended, at Tabini’s apartment, which could not reasonably be expected to threaten them, but it was the rule—one security element watched one way, one watched another. Bren walked at a brisk pace, with his two senior bodyguards. Tano and Algini moved on ahead to the lifts. Tano used his key and opened the car kept waiting at the third floor during their lockdown, no delay at all. Narani meanwhile would be closing and locking the apartment door, not to answer it for anyone except the company in Tabini’s apartment.

They entered with Algini, Tano withdrew the security key, stepped inside just as the door shut, reinserted the key in the console.

Three key-punches destined them for the train station, and the car descended in express mode, a rapidity that thumped a little air shock between levels.

They were launched. From here on out, everything was programmed, interlinked. Unstoppable. Locators on wrists, that usually flickered with microdots of green and red and gold, were quite, quite dead. So was voice communication. They were again, as the Guild expression was, running dark.

It all became next steps now, step after step after step. At this point he was no longer in charge; Banichi was; and he had no doubt that Banichi was clear-headed—that Banichi knew exactly what he was doing, how far he would have to push himself, and why he was doing it. Tabini had said it: they were one of two extant units that had the rank to lead and do what needed doing. That had been set in stone from the beginning.

So he had to be where he was, had to go where they were going to go, had to stay with his bodyguard step by step, keep up with their strides and read their cues, right into the heart of a guild whose purpose was to eliminate threats.

It was, on the one hand, insane. It was not going to work. It was on the other hand, necessary, and if it didn’t work, well, essential as he thought he was to the universe—if they didn’t succeed, he had arranged—rather cleverly, he thought—another set of clockwork gears to move, and other things would happen, things that didn’t need him and his team to survive.

· · ·

Jase-aiji’s white-armored bodyguard went first into the hall, a very strange and scary sight; and there was nobody else out—not at mani’s door, not at nand’ Bren’s. Cajeiri walked with his guests and his bodyguard, behind Great-uncle and Jase-aiji, with Eisi and Liedi tucked in behind—and all of them inside the formation of Great-uncle’s bodyguard. They walked as far as mani’s door, and stopped, with Kaplan and Polano standing frozen for the moment, no twitch, nothing that looked alive. Great-uncle’s senior bodyguard knocked, and mani’s major domo opened the door. Two of mani’s young men came out into the corridor, and then mani herself, in black lace sparkling with rubies, real ones. Great-uncle bowed and she joined them with her guard, too. She would not have been standing in her foyer waiting. Word would have passed that they were on their way, Cajeiri was sure.

And Cenedi was not with her. Neither was Nawari, who almost always was, if Cenedi was not. That was odd. They had to be somewhere about. Perhaps they were already in Father’s apartment.

They walked on down, mani and Great-uncle exchanging pleasant words. They were going to stop at nand’ Bren’s apartment, Cajeiri guessed.

But he was wrong. They just walked past that door.

So maybe nand’ Bren had gone early, too, to talk to Father.

They kept walking, with the steady machine-sound of Jase’s guard, and the tap of mani’s cane, to his father’s apartment, at the end. That door opened just before they reached it, to let them in.

Jase-aiji’s two guards took up a stance on either side of that door, and froze there, out in the corridor. Mani and Great-uncle and Jase-aiji went in, and Cajeiri did, keeping his guests close.

Father’s major domo was there to welcome them, with his staff, and mani and Great-uncle were prepared to go on to the dining room . . . but with a word to the major domo, Jegari dived off with Eisi and Liedi. Cajeiri lingered, waiting with his guests, hoping not to create a fuss.

“One is changing coats, nadi,” he said quietly to his father’s major domo, and received an understanding nod.

And because things felt odd, and because Jase-aiji had never once mentioned nand’ Bren, “Is nand’ Bren here?”

There was a slight hesitation, amid all the movement of bodyguards sorting themselves out and mani and nand’ Jase and Great-uncle going to the dining room.

“No, young gentleman, he is not. He is not expected, this evening.”

That was odd.

“Is Cenedi here?”

“No, young gentleman.”

“Indeed.” He stood there until Eisi came hurrying back with a change of coats. He shed his plain one and put on the better coat, letting Eisi help him with the collar and his queue and ribbon—and all the while mani and Great-uncle were conversing with Father’s staff, and with their bodyguards, he was thinking, Something is wrong. Something is very wrong. Has Banichi gotten worse?

He escaped Eisi’s hands, however, and, with his guests, overtook the grown-ups right in the doorway of the dining room.

“Mani,” he said as quietly as he could. “Nand’ Bren—”

Mani gave him the face sign. Just that. Face. Be pleasant. And she was not going to answer.

Now he knew something was wrong, and it involved nand’ Bren, and maybe Banichi.

But where were Cenedi and Nawari, who were always with her?

His heart was beating hard. And he had to put on a pleasant expression and smile and talk to his parents and everybody else as if nothing at all was wrong.

Which was a lie. He was sure it was.

12

It was the Red Train waiting at the siding. The oldest locomotive in service, the aiji’s own, sat lazily puffing steam and ready to roll, only three cars—two baggage cars and the passenger car, its standard formation for the aiji’s use. It was a formation everyone in the city knew: the antique black engine, bright brass embellishing its driving wheels, bright brass side-rail, and red paneling along its flanks. The door of the last car, the aiji’s own, stood open for them, old-fashioned gold lamplight from inside casting a distorted rectangle on the concrete platform. Guildsmen stood at that open door, the dowager’s men, who, as they approached, gave crisp, respectful nods and stood back to let them board.

Banichi and Jago went first up the atevi-scale steps. Jago immediately turned to give Bren a hand up, and, absent witnesses, Tano gave him an easy if unceremonious boost from behind.

Tano and Algini came right behind them, and slid the door shut before Bren so much as turned to look back.

In nearly the same moment the engine started moving, puffing as it went, a machine more in time with oil lamps than electricity, relic of a time when rail had been the fastest way to the coast. The red car had well-padded seats at the rear, a small bar stocked with crystal and linens, luxuries from a gilt and velvet age. One noted—there was even ice in the bucket.

There was leisure in their plan now, time enough to settle in the comfortable seats at the rear and try not to let nerves get to the fore. No train, modern or ancient, could run races down the curving tunnels of the Bujavid hill. The train went at its usual pace on this section of the track, and they sat, not speaking, just doing a short equipment-check. There was one flurry of green lights from Banichi’s hitherto dead locator, and Banichi said: “Everything is on time” as it went black again.

Bren drew even breaths, tried to keep his mind entirely centered in the moment, and counted the turns that brought them down the hill.

· · ·

Cajeiri sat at table in his nearly-best, in a more splendid company than they had had at Tirnamardi. The servants had had to get a cushion so Irene would be tall enough at table; but overall, looking across the table, they all three looked very fine, though very solemn, and almost too quiet. Cajeiri tried his best to be cheerful and even make them smile—but it was doubly hard, because his heart was still thumping away, reminding him that somewhere something was wrong, and people important to him were in some kind of danger.

Father’s major domo had sorted them out—Cajeiri was very glad he had not had to think about that at all, because he had far too much going on in his head. Great-uncle was opposite Great-grandmother, next to his parents’ vacant places, which insulated him from his mother—he was very glad of that, and nand’ Jase was across from Great-grandmother, and then Artur and Irene were across from him; Gene was next to him, far more comfortable company.

Even if the servants had taken all the extra pieces out of the table and moved everything up close, it was a very big dining hall. It swallowed them—and his guests were always a little uneasy in big rooms. We keep looking for a handhold, Gene had said once at Tirnamardi; and they had all laughed about it . . . as if the Earth could make a sudden stop.

But right now the feeling in his stomach made him wonder if it could.

Staff had set out the formal-dinner glassware, the state silver, the best plates. The service was a great honor to his guests. But it made it harder for them to pick the right fork. “Which comes first?” Gene whispered, and Cajeiri touched the little one above the plate, then made the attention sign they used, and signaled just a comforting, Watch me.

Then the bell rang, and the door opened, and his mother and father came in.

Everybody but Great-grandmother had to get up. Cajeiri stood up and bowed, and looked up to see his mother, who was wearing Great-uncle’s green and white, looking straight at his guests, and not smiling. She did smile at Great-uncle and him and Great-grandmother. And maybe at Jase-aiji: he was not certain—he was giving a very deep nod, and another to his father, who was solemn and sharp-eyed this evening.

His father swept a glance over everybody, the way he did when he was presiding over strangers.

And something was definitely going on. His father was preoccupied. Cajeiri saw it the second before his father smiled and nodded and welcomed everyone as if nothing were wrong at all.

Where is nand’ Bren? he wanted to ask out loud, but somehow—he thought—there was so much going on, there had been so many movements one should not ask about—shades not to be lifted, questions not to ask—that he swallowed that question and sat down quietly with his guests, hoping that whatever it was would turn out all right.

· · ·

The train picked up a little speed as it emerged from the tunnel. Tano used the train’s internal communication, at the other end of the car, to talk to the engineer.

“The switches are set,” Jago said, cited the time to the half-minute, and Banichi quietly nodded.

Two critical switchpoints, one that shunted them from the Bujavid track to the eastern track, which the Red Train used occasionally; and another, down by the canal, that would shunt them onto the ancient line that ran down to the freight yards and warehouses, and up to the ancient heart of the city.

The Red Train, in Bren’s own memory, had never taken the eastern route, let alone switched onto the central city track, and it was far from inconspicuous. People who saw that train might think that Tabini himself, one of his family, or a very high official, was on the move. They would ask themselves whether they had heard that the aiji would be traveling—and they would think, no, there had been no such advisement on the news; and with the heir’s suddenly-public birthday Festivity imminent, it was hardly likely Tabini himself would be traveling.

A high official, likely.

And what, they might wonder, was the Red Train doing on this track, headed east on a track usually carrying freight? Might it be headed for the old southern route, for the Marid?

Not likely.

Would it take the northern end of the old route, up to the Padi Valley, to the Kadagidi township? There had been trouble up there.

Both those routes were feasible—until they reached the next switchpoint.

If the operation had leaked in advance, the first indication of trouble might come with that switch not sending them onto the old freight depot spur. Bren sat waiting, as aware as the rest of them where they were on the track—and aware of the story they’d handed the Transportation Guild, who, unlike the public, knew where trains were going—or had to be convinced they did.

Tatiseigi’s men and the dowager’s had moved into the Bujavid office of the Transportation Guild with an order from the aiji-dowager. The Red Train was to shunt over to the old mid-city spur for a pickup at the freight yard—artworks for Lord Tatiseigi’s special exhibit in the Bujavid Museum for the Festivity. The fact that there actually were large crates from Lord Tatiseigi’s estate in the system waiting for the regular freight pickup after midnight . . . was useful. The fact that the large crates contained all their spare wardrobe from Tirnamardi, the things they had not had time to pack, was nothing the dowager’s men needed to explain to the operators in the Transportation Guild offices.

Perfectly reasonable that the Red Train should move to bring in crates of priceless artwork. Unusual. But reasonable. That part of the operation was the dowager’s own plan, and one they had readily adopted into their own.

The train had reached a straight stretch of track, and the car rocked and wheels thumped at a fair speed. Bren had studied the map. His own mental math and the straightaway run told him they were beside the old industrial canal, and right along the last-built perimeter of the Old City. They were coming up on their second switchpoint, if the men that were supposed to have gotten there had in fact done their job.

If they didn’t make the switch—if they didn’t, then there was a major deviation in the plan. Then, in fact—the mission changed.

Slow, slow . . . slow again. Tano and Algini quietly got up, went to the intercom at the other end of the car and waited there.

What would they do—if the switch didn’t happen?

Stop the train and deal with the situation?

Nobody had told him that part.

A little jolt and jostle then, and the train gently bumped onto the other track, slowly making a fairly sharp old-fashioned turn due south.

Bren let go a breath.

Likely so did the engineer, the fireman, and the brakeman, the personnel that ran the Red Train—all three on the aiji’s staff, elderly gentlemen, veteran railroaders in what amounted to a mostly retired lifestyle, brave gentlemen, occasional witnesses to history; and once or twice under fire. They had survived the coup—they had simply boarded another train and ridden off to the north coast, unable to rescue their beloved old engine, so it had served that scoundrel Murini for a time. But it, and they, were back where they belonged. The crew might not know the extent of the mission this time, but they had orders that had nothing to do with the freight yard: to take an unaccustomed route, stall the venerable engine at a certain prearranged point in front of the Assassins’ Guild Headquarters, and hold fast no matter what happened . . .

A mechanical breakdown was what they would radio to Transportation Headquarters, which was, ironically, just two streets over from the Assassins’ Guild.

It was a slow progress now. There were no windows in the red car, but they would be passing the very edge of the Old City, the mazy heart of Shejidan, defined by its walled neighborhoods and narrow, cobbled streets. This was the oldest track in the system—and that was another reason the Red Train, while a novelty here, was a logical choice—being of the same vintage as the handful of city engines. The sleek modern transcontinental cars that ran out of the main Shejidan rail station could not navigate the Bujavid tunnels, and while the gauge was the same, the longer cars could not manage the curves of the trans-city route. Older, shorter cars and smaller engines served the Bujavid and plied the city’s warehouse to market runs with the same equipment as they had used a century ago, cycling round and round the loop that encircled the city’s ancient center, like blood pumping from a heart to the body and back again. Older trains served the less populous districts of the continent at the sort of speed that let a provincial lord stop a train for a mail or freight pickup—which was why their incoming crates from Tirnamardi had arrived at the city freight depot. And the vintage city trains picked up mail, they picked up fruit and vegetables, flour and oil and wine, and transported them to warehouses for local pickup, or to the express line for transcontinental shipment. They occasionally stopped and quickly offloaded a stack of crates onto the public sidewalk, for one of the larger shops. They picked up passengers, usually from designated stops, but would now and again let themselves be flagged to allow a random boarding. The system halted, oh, for long enough to get a stalled van off the tracks. It halted to allow a spate of pedestrian traffic to cross up in the hotel district. Or for a large unscheduled mail pickup.

But the whole city rail was about to come to a cold, prolonged halt. The situation would be reported, after a few moments, for safety’s sake, and it would be up to the dowager’s men to guarantee the Transportation office up in the Bujavid did not rush crews to reach the train at fault . . . but that it did stop traffic.

“We are still on time,” Jago said quietly. Banichi sat staring into space, counting, in that process that knew to the second where they were, where Cenedi was, and where their support was. Banichi signaled. Locators went on.

Bren sat still, avoiding any distraction whatsoever: silence was the rule, while his bodyguard thought, watched, counted. He had the all-important briefcase between his feet. He had his vest. He didn’t want to take another hit. The last one he’d taken was enough.

But shooting was not the order of the day. Finesse had to prevent that, as long as possible, and finesse needed that briefcase, and the very heavy seal ring he wore. Needed those things, and steady nerves.

Slower still. Straight. Now he was very sure where they were, on the track that ran right through the middle of the broadest cobbled plaza in Shejidan . . . the old muster ground, which the Guilds had claimed as the last available land in the heart of old Shejidan, back when the aishidi’tat was organizing and the Guilds were becoming the institution they were now.

Slow, slow, slow . . . until the train stopped, exhaled, and sat there.

Banichi and Jago got up. Bren picked up his briefcase and stood up, letting Banichi and Jago get to the fore. He walked behind them to the end of the car where the door was, where Tano and Algini were waiting. There they waited just a handful of seconds.

From now on, Banichi led, Banichi set the pace, and it was going to be precise, once they reached a certain street lamp on the plaza. From that point, it was sixty-one paces to the steps, seven steps up to the doors, and beyond that—

Banichi gave a hand signal. Algini opened the door and stepped out into the twilight, not at the usual platform height. Algini landed on his feet below, Tano did, and the two of them immediately pulled spring pins that released three more filigree brass steps.

Banichi descended. Jago did. Bren took the tall steps down and used Jago’s offered hand to steady him as he dropped to the cobbles.

The car was sitting close by the lamp post in question, in front of the featureless black of the Assassins’ Guild Headquarters . . . a building as modern-looking as anything one might expect over on Mospheira. Its design made it a block, slits for windows, black stone with inset doors, with none of the baroque whimsy that put a lively frieze of an ancient open-air market around the Merchants’ Guild, or a staid and respectable set of statues to the Scholars’ Guild that sat next to it. The Assassins’ Guild just looked . . . unapproachable, its doors, as black as the rest of it, set deep in a relatively narrow approach. Wooden doors, Banichi had told him. Ironwood. It took something to breach that material.

But those outer doors should not routinely be locked. Banichi had said that, too. They were not supposed to be locked. They could be. The inner door definitely would be.

They reached the lamp post. He thought Banichi might pause there, if they were somehow off their time—but Banichi and Jago kept going. It was his job to stay with them, and Tano’s and Algini’s to stay with him. It was a pace he could match if he pushed himself. Banichi said speed mattered. But it couldn’t look forced to any observer, just deliberate.

Sixty-one paces. They crossed the cobblestone plaza on a sharp diagonal, crossed the scarcely-defined street, and the modern paved sidewalk that skirted the Guild’s frontage.

Seven steps up to the iron-bound doors, which might or might not open.

At the last moment Banichi touched something on his locator bracelet and Jago pounded once with her fist on the dark double doors.

There was a hesitation. Then a latch clicked and the left-hand door, where they were not, swung outward—a defensive sort of door, not the common inward-swinging sort. Guards in Guild uniform confronted them.

“The paidhi-aiji,” Banichi said, “speaking for Tabini-aiji.”

Bren did not bow. He held up his hand, palm inward, with the seal-ring outward.

The unit maintained official form—the two centermost stepped to the side, clearing their path without a word of discussion.

They were in.

Bren went with Banichi and Jago in front of him and Tano and Algini behind. It was the tail end of a warm day at their backs. The foyer swallowed them up in shadow and cool air, and three steps up led to a hallway of black stone, where converted gas lamps, now electric, gave off a gold and inadequate light beside individual office doors. Antiquity was the motif here. Deliberate antiquity, shadow, and tradition.

Hammered-glass windows in the dark-varnished doors. Black stone outside . . . and that glass in those doors was, Bren thought, all but whimsical—a show of openness, even of casual vulnerability . . . in the fifteen offices that dealt with outsiders to the Guild.

These outer offices had nothing to do with Tabini-aiji’s order. A business wanting a guard for a shipment, yes. Someone with legal paperwork to file. A small complaint between neighbors. A request for a certificate or seal. It was the national judicial system, where it regarded inter-clan disputes.

The aiji’s business had no place in this hall, which led past the nine offices of the main hall toward an ornate carved door, and at the left, a corner, with six more offices in a hall to the left, just as described.

Two guards at their backs, down those three steps to the double-doored entry. Four guards at a single massive wooden door, this time.

“The aiji’s representative,” Banichi said, and a second time Bren held up his hand with the ring.

This time it was no automatic opening of the door. “Seeking whom, paidhi-aiji?”

“The aiji sends to the Guildmaster, nadi, understanding the Guild Council is in session this evening.”

There was no immediate argument about it. Guild queried Guild, communicating somewhere beyond those doors.

Bren waited, his bodyguard standing still about him. It was thus far going like clockwork. Neither of these outer units should have the authority to stop them.

“The paidhi-aiji,” the senior said, in that communication, not in code, “bearing the aiji’s seal ring, a briefcase, and with his own bodyguard.”

There was a delay. The senior stayed disengaged from them, staring across the hall at his counterpart in the second unit. There might have been a lengthy answer, or a delay for consultation. And there might yet be a demand to open the briefcase.

The senior shot a sudden glance toward Bren. “Nand’ paidhi, the Council is in session on another matter. You are requested to wait here.”

“Here?” Indignantly. They needed to be through that second set of doors. Bren held up his fist, with Tabini’s ring in evidence, and put shock in his voice. “This, nadi, does not wait in the public hall!” With the other hand, he held forward the briefcase. “Nor does the aiji’s address to the Guild Council! If the Council is in session, so be it! This goes through!”

“Nand’ paidhi.” The senior gave a little nod to that argument and renewed his address to the other side of the door. “The paidhi has the aiji’s seal ring, nadi. He strongly objects.”

There was another small delay. Nobody moved. There was an eerie quiet—both in their vicinity, and from all those little offices up and down the two halls that met here. What was going on back at the outer doors, at any door along that hallway, Bren could not tell. One could hear the slightest sound, somewhere. Atevi ears—likely heard far more than that, possibly even the sound of the transmission.