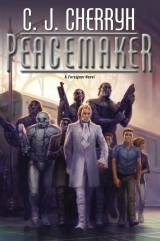

Текст книги "Peacemaker"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The ship’s crew voted to take aboard those colonists who wanted to leave, and go. They went a year out into deep space, to a star with resources of metal and ice. There they set up a station they called, optimistically, Reunion.

From Reunion, the ship continued its exploration, through optics, and by closer inspection. The crew no longer hoped to find their own Earth, but they did hope that by increasing the human population at Reunion, then, from Reunion, establishing other colonies at planets or moons of some attraction—they could then revisit the population they’d left at the Earth of the atevi and convince them there was an alternative to landing.

Alternatives, however, did not immediately present themselves. The station at Reunion grew. But there was no suitable world. More troubling still, in one direction, they found the signature of another technological presence.

Back at the first station, from the week of Phoenix’s departure, the authorities had begun losing control. All that had stopped the colonists from going down to the Earth in the first place was the simple fact that, among the colonists or on the ship, there was nobody who knew how to land in a gravity well, or fly in an atmosphere, with weather and winds. Phoenix itself had been fairly confident that the colonists would, without the ship’s crew, have to agree among themselves to survive, and that the solution would not involve experimental manned landings on the planet.

But the colonists had a considerable library. And in those files they found a means within their capability to build, to aim, and to operate.

They pointed it out to the station aijiin.

They demanded action.

The station aijiin gave in. They built machines that would land in undeveloped land, and explore. If those reported well, they would build a craft to land by parachute, that would carry a scientific team, such as they could muster.

Those would go first.

All went well down to the second stage. The team, composed of names still honored by place names on Mospheira, met the tribal peoples . . . and after a brief period of good report and apparent progress—they vanished, with no clue, even to later generations.

The program was shut down, and remained shut down, for a long time. But dissatisfaction grew, in claims the station aijiin had been too timid. There were other places. There was empty land, even on the island. There was a whole other shore. There were extensive forests. There were vast plains where no one at all lived. There was a very large island south of the main continent.

Station authorities tried to silence the idea. The population had increased, but the space station had not. The ship had taken away the machinery that might have let them add more room easily. And then supplies began to disappear.

Small conspiracies assembled simple life-support for small capsules, shielded against the friction of the atmosphere, and provided with only one button, which would blow the shield off the parachute in the event the sensors that should do that automatically—failed.

By twos and threes they launched these fragile capsules toward the gravity well, and parachuted down.

When colonists learned the first capsules had come down safely—and more, that they were welcomed—more and more groups fled the station. The station-aijiin attempted to find and destroy these efforts, and the desperation of the colonists only increased. Workers refused to work. Groups stole materials in plain sight, and threatened anyone who tried to stop them. And the station grew more empty, and shut down, second by section. Those manufacturing materials said openly what they were for, and a small group exercised discipline enough to keep the effort going despite the objections of station aijiin.

Their technicians deserted. Station maintenance suffered. At the very last there was no choice for the administrative and systems managers but to join the movement. They mothballed the station, set the systems to maintain stable orbit so long as they could, and parachuted their armed bodyguards and themselves to the planet.

The last sudden band of humans, who emphatically resented being there and did not want to adapt to the planet in any way, changed everything.

Atevi suddenly attacked, for no reason humans understood.

In fact atevi had long since been pushed past the limit, and when they met the managers and the large load of weapons, they had finally pushed back.

iii

<

Coastal associations responded. Then the aiji in Shejidan moved to assert control, and took over leadership in the War of the Landing: this absorbed the last western clans still holding apart from the aishidi’tat, and eventually brought the Marid in as well.

The aiji formed a strategy to contain the problem reasonably rapidly: to push the humans off the continent and onto Mospheira, where the greatest number of humans were already living. Mospheira was the home of the Edi and Gan peoples, who had first met the humans, and who were part of the bloodiest action, but they were not part of the aishidi’tat, and were not Ragi, nor of the same customs. They persisted in attacking the humans on their own, with disastrous results.

The aiji offered the tribal peoples refuge from the fighting, in two small areas of the west coast where they could pursue their traditional ways and their livelihood of fishing. Without attacks coming at them on the island, humans found it a place of safe retreat, and centered their non-combatants there—which left only the most aggressive humans on the continent, exactly the situation the aiji wanted. The humans on the mainland could now be attacked and maneuvered into small pockets that could be cut off.

The War of the Landing ended with the humans on the mainland cut off from supplies, with no way back to the space station, and with no prospect of rescue from the island, or even of retreat to it, since the forces from the Marid held the strait. The aiji in Shejidan offered these groups a choice: extermination, or a way out. Humans might have ownership of the large and rich island of Mospheira, the conditions being first, total disarmament—the weapons they had were to be taken out to sea and sunk.

Secondly, and this was why the aiji was so generous: surrender of the technology. In return for an untroubled sanctuary, the humans were to send a paidhi to Shejidan to live, to translate, and to supervise the gradual turnover of all their technology to the aishidi’tat—namely to the aiji . . . and they were not to build or use any technology that was not approved by the paidhi.

The desperate humans had a very limited understanding of what a paidhi was. They understood that he was to mediate, translate, and that he would be their official in the aiji’s court, so they picked the most fluent Ragi speaker they had, hoping to stall off any demand for their weapons technology.

That was very well, the aiji said to them, through the paidhi they sent. There would surely be areas of agreement, and very useful things would serve.

That any knowledge could be turned to other purposes, and that atevi scientists were already finding out the secrets of foreign machines they had captured, was something the aiji failed to mention.

That there was still a starship the humans hoped would someday return was a matter humans had failed to mention, on their side.

But that agreement brought sufficient peace: this was the Treaty of the Landing, on which all our dealings with humans have been based. The Foreign Star, empty, continued to orbit the world.

Humans, vastly outnumbered, set about transforming Mospheira to suit themselves.

The aiji in Shejidan argued convincingly that the association atevi had formed to defend themselves should not be dissolved, since who knew if there were more humans to arrive from the heavens?

The allied association of the Marid had joined the aishidi’tat at the last moment, and would not accept the guilds: it maintained its own. Likewise the East was not yet part of the aishidi’tat in any permanent way.

But in the same way atevi had built the railroads, they had found pragmatic ways to work together—and the number-counters found fortunate numbers in the suggestions of an extension of the association—so it was felicitous that the Western Association, which was no longer just western, should stay together to respond quickly to any further difficulty from the humans on Mospheira.

The lords of the outlying clans and the regions, the aiji said, all should sit equally in the legislature in Shejidan, and they should all have a say in the laws of the aishidi’tat, the same as those born to the cental region.

The aiji further divided the entire continent into defensive districts, and these became provinces, with their own lords, also seated in the legislature. This added a few extra votes to critical regional associations, to balance the dominance of Shejidan: this pleased the lords.

The aiji then went to the guilds with another proposal: that, as they had all worked across regional lines during the War, they should continue after the war, adding a special privilege and formal principle. The guilds of the expanded aishidi’tat should have no respect for clan origin in candidacy for membership or in assignment: in fact, the guilds of every sort, like the Assassins, like Transport, should become their own authority, assigning members to posts only based on qualification, officially now without regard to kinship, regional association, or clan. This placed all power over membership into the hands of the guild masters.

The heads of the various guilds, interested in maintaining the power they held under war conditions, saw nothing but advantage in the aiji’s proposal. The idea was less popular with some of the regional associations, who still held apart from the guild system—but in the main, it became the rule, not by statue, but by internal guild rules, and there was nothing the regional associations or the newly created provinces or the clan lords could do about that—if they wanted guild services.

The Assassins’ Guild, in private conference and at the aiji’s request, agreed to one additional rule, that no one of their guild could seek or hold a political office or a lordship. They received a concession in exchange: that, as they were barred from politics, they would have certain statutory immunities from political pressure. Their records could not be summoned by any lord, their members would testify only before their own guild council, and the disappearance or death of any member of that guild, granted the unusual nature of their work and the extreme discipline imposed on the membership, could only be investigated by that guild and dealt with by that guild, by its own rules.

There were other, more detailed, provisions in that Assassins’ Guild charter, and there were peculiar ones, too, in the regulation of other guilds, and also in privileges granted the residents of Shejidan, to have their own officials, independent of any clan.

It was a tremendous amount of power the aiji let flow out of his hands.

But it also meant the aiji in Shejidan gained the support of the city and all the guilds, and now outvoted any several regional lords.

And from that time, the Assassins, freed of political pressure, became not only the law enforcement of the aishidi’tat, but the check and balance on every legal system, the unassailable integrity at the heart of any aiji’s rule.

The new principle of guild recruitment across clan and regional lines had an unintended consequence. It brought ideas into contact with other ideas, and fostered a flowering of arts and skills, invention and innovation—a cross-pollination that within a few years ended one major cause of wars. Even the domestic staffs that served a clan lord might be from different clans, different regions, and different philosophies, all working together.

It was, in that sense, an idyllic era of growth, discovery, and change—with occasional breaches and dissonances, true—but the clan feuds grew fewer, and more often bloodless, to the wonder of those who thought in the old ways, and distrusted the new.

There were two exceptions.

There had once been a great power in the southern ocean, which had conquered and colonized the Marid before the Great Wave had destroyed all the seaboard cities on the Southern Island. The Marid, of a culture separate from the north, had been reaching for the west coast before the petal sails had begun to fall . . . and while it had cooperated with the aishidi’tat during the War of the Landing and remained officially a member after the Treaty was signed, it refused to allow what it called the Shejidani guilds to make any assignments in the Marid—and it did not have all the guilds. It maintained its own recruitment and training centers for the Assassins, the Treasurers, the Merchants, the Artisans, the Kabiuteri, and the Builders, as well as some unique to their region. The five clans of the Marid united only infrequently, maintained their seats in the legislature of the aishidi’tat, and their disputes frequently resorted to warfare among themselves.

The Eastern Association, headed by Malguri from the time of the War of the Landing, was the second isolate entity, a vast territory walled off from the west by the continental divide, and by the storms of the Eastern Ocean. Its small clans and its three cultures had united with the West for the first time in the face of the threat from the heavens. But after the Treaty, as before, Easterners hunted, fished, and worked crafts, never having formed the guilds that were so important in the rest of the world.

They were, however, fierce fighters, and one guild had gotten a toehold in the East during the War of the Landing—the Assassins. They had organized their own training, their own guild hall, and ran their own operation in the East during the War. The Eastern Assassins’ Guild affiliated itself with the Guild in Shejidan. It allowed certain of their members to be assigned by the Guild in Shejidan—but allowed no outsiders to come in. They were good, they were impeccably honest, they were in high demand because of their reputation, and recruitment was easy because of the general poverty of the East. But the East was otherwise separate from the guild system of the aishidi’tat . . . until Ilisidi, aiji in Malguri, was courted by the aiji in Shejidan.

Ilisidi-aiji brought a great deal to the marriage. She joined the vast territory of the East to the aishidi’tat. She had her own opinions, and voiced them, and being widowed, she continued to voice them in support of a list of causes including opposition to human presence, opposition to industrial encroachment, support for the environment, and concern for the unresolved west coast situation in the regions facing Mospheira. She maintained a considerable and independent bodyguard, larger than any other lord in the East or the west, and when widowed, she refused to give up her young son to the aiji’s maternal grandfather.

She maintained control of the Bujavid, made herself aiji-regent, since she did not succeed in having the aishidi’tat accept her as aiji in fact—and she simultaneously refused to leave Shejidan—while she kept an iron control of Malguri. She continued well into her son’s majority to have her own agenda, and her own very large bodyguard, which by now had extended her authority over the entire East, and which maintained her safety, even in annoying a number of the powers of the aishidi’tat in Shejidan.

Her son, Valasi, finally succeeded in establishing his own authority as aiji in Shejidan, with the help of the Taibeni clan of the Padi Valley, his grandmother’s clan, and others of the north and mountain regions. He was twenty-seven by the time he made his bid for power, and Ilisidi conceded to him, finally, as he gained sufficient votes in the legislature.

Valasi made a contract marriage with a woman of the Taibeni, quickly produced an heir as insurance, and found it convenient to follow that contract marriage with several others, of whatever region he needed to draw more firmly into his hands. This bedroom diplomacy solved several petty wars.

He also gained several important technological advances through his partnership with Wilson-paidhi, including aviation and early television, and in all, had a strong grip on power, while he avoided having his eldest son in the hands of his various wives by putting young Tabini into Ilisidi’s hands and urging the aiji-dowager to keep Tabini safe in her own estate at Malguri.

This kept his minor son and Ilisidi both separate from the center of politics. It kept the center of the aishidi’tat very happy, in the absence of their chief irritant, the aiji-dowager, but Valasi’s concentration on trying to keep power out of Ilisidi’s hands had left the west coast of the aishidi’tat embittered: they viewed Ilisidi as their ally, and her departure to Malguri as Valasi’s definitive refusal to deal with their problems.

The west coast clans, notably the Maschi at Targai and Tirnamardi, had been forced to play a cautious kind of politics, balanced between the Edi tribal people, who supplemented their traditional fishing with piracy and wrecking, and the Marid clans, who saw the west coast as naturally theirs. Marid shipping was the principle target of the piracy. The Marid at times pursued their aims with contract marriages in the west, but all the same, given the resentments of the Edi people, unwilling settlers on that coast, and clan wars inside the Marid, all these moves came to was a generally unsettled condition on the west coast. The north coast fared somewhat better, in the happy relationship of the Gan tribal people with their nearest neighbors, also mariners, on the island of Dur—

But the adjacent Northern Association, while not in the same ferment as the south, and somewhat inland, had its own ambitions. The head of the Northern Association, within the aishidi’tat, was the lord of Ajuri clan . . . and he, pressed by a struggle inside his own clan, arranged the marriage of a young relative, Komaji, to an older lady of the ancient Atageini clan—the Atageini lord being one of the closest allies of the aiji-dowager, and at the moment engaged in politics with Valasi-aiji, in a dispute with their nearest neighbors, the Kadagidi.

It was a marriage of great potential value for Ajuri. It proved, however, unfortunate, in the death of the Atageini lady soon after the birth of a daughter, Damiri, under circumstances some called suspicious. Lord Tatiseigi of the Atageini, in a heated confrontation with Komaji, handed over the baby to Komaji, thus breaking the association with Ajuri and terminating the Ajuri hope of having a relative in an influential position within the great Atageini house.

Valasi-aiji managed to patch the quarrel between the Atageini and the Kadagidi, and simultaneously prevented the Atageini lord from Filing Intent on Komaji. He also kept the southwest coast out of the hands of the Marid, and had got control of the aishidi’tat back into western hands and out of the hands of the aiji-dowager.

Valasi was accounted a great aiji.

He died unexpectedly, however, with his heir still short of the twenty-three years of age required to be elected aiji.

The aiji-dowager returned to Shejidan with her grandson Tabini and applied to be elected aiji herself, citing the complex business of the aishidi’tat, particularly in view of increasing traffic with the Mospheirans, who were beginning to colonize neighboring Crescent Island, and who were developing industry without restraint—a matter which left the northwest coast of the continent on the receiving end of the smoke and the effluent.

She repeated her argument that several areas of the aishidi’tat remained a problem, since they had been stop-gap arrangements following the War of the Landing; and she also proposed tough new negotiations with Mospheira about the protection of the environment.

The legislature balked . . . on all points. Regional interests did not want pieces of the post-War treaty reopened, for fear of having their pieces of it reopened. The Marid certainly did not want her solution to the west coast problems, and nobody but Dur cared about smoke that was mostly landing on the Gan peoples, since they had never signed on to the aishidi’tat.

Ilisidi ruled as aiji-regent through the last of Tabini’s minority and through the last years of Wilson-paidhi’s service, aided by a Conservative coalition headed by Lord Tatiseigi of the Atageini.

Meanwhile Damiri, now a young woman, disaffected from her Ajuri father and angry, deserted a family outing during the Winter Festivity in Shejidan and presented herself to her influential Atageini uncle, asking to be taken in by Atageini clan. Lord Tatiseigi, who had not sought this, and in fact had only resumed relations with Ajuri at all to further the aiji-dowager’s cause, saw in the young woman her mother in her youth. Being himself childless, and the holder of a great political power which teetered constantly on the edge of disaster because of that—he sent a conciliatory letter to the Ajuri lord, saying that he had found the missing young lady, that she was, typical for the child of a contract marriage, having a crisis of man’chi, and that he would be willing to entertain his young niece until she grew equally dissatisfied with the fantasy of life in her mother’s clan.

In point of fact—the observation was not a lie. But Lord Tatiseigi likely had no intention of letting the young lady grow dissatisfied with her Atageini heritage. She was indisputably of his bloodline, she was pretty, she was intelligent, certainly enterprising, and he needed an heir, which, baji-naji, he had not produced. The Ajuri marriage originally had had that consideration. If she came still with an unfortunate attachment to Komaji of the Ajuri, he judged that a surmountable difficulty. The Atageini were richer, more powerful, had a stronger influence in government, and if the young lady attached man’chi to him rather than to Komaji, he might have what he greatly needed.

So things ran for that year. Tabini passed his twenty-third year.

And finally, mustering an unlikely but temporary coalition of the Taibeni, the Kadagidi, the Marid, the mountain clans, and the Northern Association—Ajuri was all too ready to support anybody but the aiji-dowager, who was Tatiseigi’s political patron—Tabini was elected aiji in his own right.

People feared there might be a confrontation—extending even to armed conflict and the breakup of the aishidi’tat if the aiji-dowager would not relinquish power. Some even feared humans would take advantage of such a conflict and attack the mainland. People were storing food in their houses and the requests to the Assassins’ Guild for hired protection in such an event were reportedly unprecedented.

The aiji-dowager and Tabini-aiji, however, appeared together on that new and still-rare medium, television, as well as radio, and the aiji-dowager congratulated her grandson on his election and wished him well.

The aishidi’tat, and indeed, the human population on Mospheira, breathed a sigh of relief. Wilson-paidhi, notorious for granting Valasi whatever he wanted, to the extent the aiji-dowager feared a human plot to undermine atevi morals, withdrew from public life entirely, in deep disfavor with, now, the new aiji, and wanting only to get off the continent alive.

The aiji-dowager retired to Malguri, with occasional visits to her apartment in the Bujavid, visits notable for their tension and difficulty.

Tabini, as aiji, did as he had said he would do: he dropped the environmental matters—telling his grandmother he would revive that negotiation once Wilson-paidhi finally retired, a decision he was trying to hasten. Tabini also conducted several actions designed to protect the west coast from the Marid’s ambition, including a promise to the Marid to protect their shipping from piracy—and he used that as a pretext for an order increasing the size and armament of the Mospheiran navy, incidentally strengthening his position regarding Mospheira.

He needed the Conservatives on board, and found his opportunity to gain the man’chi of the aiji-dowager’s chief ally, Lord Tatiseigi—when he met Tatiseigi’s niece, Damiri.

Wilson-paidhi retired. Tabini-aiji was far from a technophobe, and had always a deep interest in technology of every sort, different from Valasi-aiji, who had primarily pressed Wilson-paidhi for things his advisors thought might lead to better armaments—wires were one such development. And in this he differed from Ilisidi, who deeply distrusted and despised everything human, and who had mostly treated Wilson-paidhi as an adversary—one she had to force to carry her ecological concerns to human authorities, and whom she considered utterly and foundationally unreliable.

There was had a crisis looming in the Marid, and a report of a suspected fracture in human politics—possibly worse if fed by what Wilson-paidhi could say, once he began to talk to his superiors and possibly to persons less discreet. Nobody had ever trusted Wilson-paidhi. No one could tell whether Wilson-paidhi was having a good day or not. After Wilson-paidhi’s decades on the continent—as a translator—nobody on this side of the straits could tell what Wilson-paidhi thought, what he felt, what he was reporting to his government, whether it was accurate or whether Wilson-paidhi even knew whether it was. No one had been able to tell, especially lately, whether Wilson-paidhi was, in fact, an enemy or outright unbalanced. Some of his actions had given the latter impression . . . and in fact there had been some suggestion that the wisest course for Tabini-aiji to take on Wilson-paidhi’s retirement was to have Wilson-paidhi meet an accident while he was still in reach, and before a madman reached the island enclave and began to report imaginary wrongs and insane plots.

He might be served the wrong sauce at dinner, perhaps, or tread on a waxed marble step. The man was fragile as porcelain, and moved like it. He had no bodyguard. He was entirely undefended, and Tabini-aiji personally doubted the humans on Mospheira would raise too great a fuss about losing a man who was, after all, on his way out and more than a little strange.

Tabini-aiji made up his mind, however, to send Wilson-paidhi home unscathed, and not to begin his new relationship with humans, about whom he was intensely curious, with an assassination—or to initiate a crisis which might have the humans declining to send a paidhi without certain assurances. That could lead to a serious crisis in international affairs, and if he ever granted any assurances, it would set a very bad precedent. A diplomatic standoff would not be a good beginning at all . . . not for an aiji who wanted concessions from humans.

Tabini-aiji even assigned two of his personal bodyguards to get Wilson-paidhi safely onto a plane, against the not-too-unlikely chance that some other power—such as the aiji-dowager—might decide Wilson should not report all the details of his dealings with her.

Tabini-aiji could not be sure what humans would send him: another old stick of a man like Wilson-paidhi. A determined ideologue. A person with an agenda of his own.

He was absolutely delighted to have a paidhi his own age. And one who spoke, more to the point, without writing things down and consulting his dictionary.

Before, however, any sort of relationship could develop, given the situation Tabini-aiji was hearing about on Mospheira, and the situation in the Marid, and his own contemplated relationship with Lord Tatiseigi’s niece—he needed to enlist Ilisidi, who had reared him, not as his potential adversary, but as an ally.

She had retired to Malguri, that ancient fortress, holding occasional meetings with her Eastern neighbors, meetings regarding him, he was sure.

Someone made an attempt on the new paidhi’s life.

Tabini-aiji was far from surprised that would happen. He had assigned the new paidhi bodyguards. He had given the new paidhi a very illegal firearm and seen to it the new paidhi had at least rudimentary instruction in using it and hitting a target.

Tabini-aiji had made himself look as innocent of any harm to the paidhi as he could possibly look, inviting the paidhi to a retreat at the Taibeni lodge he favored for brief holidays, making him a personal guest—which would signal most people inclined to make a move against the paidhi that they would have him to deal with.

His grandmother had, however, said she would like to talk to the new paidhi. His grandmother was undoubtedly expecting Tabini to keep his word and open a discussion with Mospheira about the smoke.

And if there was one person who could breach his grandmother’s private fortress at Malguri—and convince his grandmother that they were dealing with somebody very different from Wilson-paidhi—it was the person about whom she was most curious.

He attached bodyguards—and sent the new paidhi to the aiji-dowager.

He knew his grandmother very well. He had gained her attention.

She knew what her grandson was up to. And she came back to Shejidan of her own will, intensely engaged—suspicious, but engaged. And Bren-paidhi was, for his part, likewise engaged.

That engagement completely changed the political landscape. It drew Lord Tatiseigi, however reluctantly, into Tabini’s camp—which was doubly convenient. The match with Damiri became possible . . . and that was a more than political matter, which could be done with a contract marriage with or without an heir produced. Tabini-aiji wanted Damiri-daja, not as a contract marriage, but in a way lords rarely arranged their relationships, as a lasting marriage and a lifelong ally.

It complicated matters that Damiri had, predictably, had her differences with her uncle Tatiseigi and gone off to her father now and again. Ajuri was a minor clan, and it was the matter of a little unfortunate public attention. He sent Damiri-daja a letter. He sent one to her father and to her uncle. He wanted her to take up residence in Shejidan, with him, he wanted a reconciliation of Ajuri clan with her uncle, and he wanted a formal marriage—